|

The province of

Manitoba—The realization of “Sea Dreams”—Civic and agricultural

growth—Winnipeg—Railway enterprise—The Canadian Pacific and Grand Trunk

Railways —System of Government—Schools—Public Park—Prices of

produce—“Ralph Connor”—The Canadian Northern Railway —Winnipeg to

Edmonton—The chance of a millionaireship —Edmonton—The lady and the “

gentleman ” bus conductor— Colleges and schools—Churches and drinking

saloons— Vegetable products — Edmonton to Calgary — Flourishing

agriculture.

WHEN we think of the

years necessary to achieve the wealth and splendour of nations, and look

at the Province of Manitoba, it almost seems as if some good genius had

waved her wand, and lo, a barren lonely marsh and wild prairie are

suddenly changed, and golden harvest-fields, lowing cattle, model

dairies, comfortable homesteads and happy children rise as if by magic

before our eyes. We not unnaturally ask, “Whence came these?” and then

think of the city clerk’s vision in Tennyson’s “Sea Dreams,” of a woman

grown to enormous strength by “working in the mines,” and like him wake

to realize that honest toil—hard and matter-of-fact—is the secret of

collective as well as individual growth.

PRINCE ALBERT BRIDGE,

The wealth that lies in

the rich soil of this vast territory justifies the legend. Its output is

seen in prosperous cities and towns, rapidly spreading far and wide.

When Manitoba incorporated itself in the Confederation in 1870, it had

17,000 inhabitants, and now upwards of 400,000 English-speaking people

form its population. In 1870, its agricultural produce was not even

recorded. In 1881, an acreage of 51,300 yielded 1,000,000 bushels of

wheat, and 1,270,268 bushels of oats. In 1905, these odd millions jump

up to over 55,000,000.

Only 5,000,000 acres of

land are at present under cultivation, a patch compared with the actual

possibilities, as Manitoba is larger than Scotland, Wales and Ireland

combined, and contains 74,000 square miles of territory. Of this

30,000,000 acres are arable land.

Winnipeg is the seat of

the Government, and holds a foremost place amongst the cities of the

great continent. It is called The Gateway to the West. Its growth has

been extremely rapid, and it possesses all the modern conveniences of a

great centre. London has nothing to compare with its spacious streets,

and New York can scarcely out-do it in sky-scraping buildings. Electric

cars run in every direction, and public parks and promenades are

provided for the pastime and enjoyment of its thriving citizens. Its

thoroughfares are daily crowded with busy merchants, many of whom are

the descendants of the early Scotch colonists who reside in imposing

residences on the outskirts of the town. A walk in that direction shows

that Winnipeg, like all great cities, is cultivating suburban life.

New towns and villages

are quickly springing up, contiguous to agricultural and manufacturing

districts, and in the rapidity of their growth make Winnipeg the Chicago

of the Dominion.

The great incentive to

development has come from railway enterprise. The Canadian Pacific

running from east to west has many branches which bring settlers within

reach of rich agricultural soil, The Grand Trunk system, and the

Canadian Northern, each exploring different territory, have done much in

opening easy avenues for the transit of grain and stock to Winnipeg and

other important centres where traders find remunerative markets. Indeed,

one can see, in addition to provincial economic advantages, the

possibility of new routes by land and sea to and from and across the

Dominion through what is now a daily event—the extension of these great

railway systems.

Amongst other valuable

services rendered by the Government is the issue of reliable information

on trade and agriculture. There are annual returns from the Provincial

and Dominion Board of Trade which can be accepted as bona fide.

Emigrants and settlers are no longer the dupes of advertising agents and

others with axes to grind. The returns are too

good to need

embellishment or exaggeration, and any figures which are quoted here

have the imprimatur of the high authority to which I have referred.

The Government of

Manitoba is administered by a single Legislative Chamber, and executive

Council on practically an electoral basis of manhood suffrage. The

public school system is excellent, and entails the largest expenditure

in the annual budget. Public works come second, and the administration

of justice third. Schools are free to all children between the ages of

five and fifteen. In larger towns resident pupils are free to the high

schools and colleges. They are maintained largely by Government, who set

apart sections of land in each township which yield part of the revenue;

the rest is provided by a land tax. The growth of these schools is an

index to progress. In 1886, the number in the province was 422, with an

attendance of 16,834. In 1906 there were 1,847 schools and 64,123

scholars. Schools of agriculture are also provided, and associations for

instructing the settlers’ children in live stock, fruit growing, dairy

farming, and practically every branch of industry within the province

requiring skilled labour.

There is an excellent

tram service to the outskirts of the city, where there is a fine park,

containing zoological gardens which hold good specimens of bear, wapiti,

mountain goat, beaver and other animals. The Red River flows through the

park, on which motor boats and yachts were sailing. The wild features of

the place are preserved intact, and shady nooks and vistas of spreading

trees lend their charm. It was intensely hot, and seeking a cool retreat

I lay down and went fast asleep. A singular sensation awakened me, and

on opening my eyes I got a glimpse of a brown animal scuttling into the

grass, about the size of a gopher. He did not give me time to classify

him, but left a distinct impression on my face, over which he ran.

Commodities in Winnipeg

vary in price according to the supply ; apples very cheap ; oranges very

dear, 2\d. each ; plums of an inferior quality, 5d. a pound. On the

other hand, restaurants which almost jostle each other in the streets,

provide an excellent luncheon for ij. 3d. Hair cutting is a luxury ;

half a dollar, or 2s. 1d. in English currency, is charged for trimming

one’s beard, which had the effect on one forlorn traveller of making him

vow that henceforth he would become a Nazarene.

I spent a couple of

delightful hours with “Ralph Connor”—Rev. Charles W. Gordon—who, in

addition to his literary career, is a distinguished leader in the

Presbyterian Church. He has seen Winnipeg grow from the day of small

things, and watched men on the spot develop from obscurity into opulent

merchants.

I have alluded

elsewhere to his place in literature.

HEAVY CHOP, MANITOBA

He is an ardent

disciple of Isaac Walton, and as we had travelled over similar ground it

was pleasant to compare notes. He is saturated with the mystery and

grandeur of the Rocky Mountains, the full aroma of which pervades his

books. His influence in the higher walks of his profession has made him

the original of “The Sky Pilot” he has so well portrayed.

Singularly enough,

another leader in the religious life of Winnipeg is the Rev. J. L.

Gordon, with whom the novelist is often confused. The former, upon whom

I also called, narrated a number of cases of mistaken identity between

the minister and the author. The error is by no means uncomplimentary to

“Ralph Connor,” as his namesake is a strong personality and one of the

most popular preachers in Canada. Each has cut deeply in his own line,

and both possess a charming grace and simplicity.

A railway recently

constructed by the Canadian Northern runs from Winnipeg to Edmonton, a

distance of iooo miles. It traverses an undeveloped territory through

the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. With the exception

of an occasional farm homestead between the stations, at which the train

stops, its course is through virgin soil.

The advent of the

railway gives an enhanced value to the adjoining land. It is the

philosopher’s stone, which turns base metal into gold, or, better still,

the wilderness into a fruitful plain. It affords facilities, for the

opening up of markets, the transportation of agricultural implements

which are absolutely indispensable in a region where labour is scarce at

best, and at times altogether unavailable. Without the railways, the

wealth of the prairies, as well as of forest and mine, is a locked-up

good, as unreachable as the gem of “ unfathomed caves of ocean.” Men may

buy the land, sell it, gamble in it, but it does not become a workable

asset until it is linked up with the towns and cities near and far. The

great waterways, valuable as they have been, can never become

substitutes as a means of transit. The method is slow, and if it affords

easy access to a district, it is in the same proportion difficult of

egress. A farmer may look at the golden grain and the smiling fruit, and

the fattening kine, and eat his heart out for the long-delayed

opportunity of exchange, which is the basis of all commerce.

The Canadian Northern

Railway, extending from Port Arthur to Edmonton via Winnipeg, has opened

up important territory. The effect was to be noticed in the activity at

every stopping-place along the line. There were houses newly erected,

and others in the course of construction. Barn-like structures

advertised themselves in large letters as hotels. Telephone wires

stretched from hut to hut, and agricultural implements, fearfully and

wonderfully made—at least to the lay mind—were piled near the stations.

Every platform was a

mart where farmers, agents, and speculators were there and then willing

to sell desirable sites and thriving farms. Judging from what I heard, I

might have been a millionaire, had I only the temerity, half a dozen

times over before reaching my destination. This spirit of

disinterestedness on the part of vendors has been checked of late years

by the formation of reliable bureaus under Government supervision. There

is no longer any necessity for a purchaser of land to find himself in

possession of a swamp, a by no means uncommon experience. The Prairie is

not a uniform El Dorado. It has its arid wastes, its thin substratum of

fertility, as well as its deep rich loam, and there hover over it all,

hawks which are ready to pluck any unwary bird about to stretch its

speculative wings.

The journey to Edmonton

is in itself an object lesson in inequalities. Great rivers are crossed,

cutting their sinuous way through vast plains, pregnant with the highest

possibilities of agriculture. Rocky soil comes into view of a different

order and more limited in productive qualities; lakes with great

stretches of marsh, out of which flocks of wild duck rise, attesting its

suitability for their habitat and little more.

It was late when we

arrived at Edmonton, the capital town of Alberta. A number of omnibuses

were drawn up at the station for the convenience of passengers. Choosing

that more archaic method of travel rather than the electric trams, I

found myself in company with half a dozen others, rattling over the

worst roads possible to imagine. The outskirts of Edmonton, like most

new Western cities, have to wait on their betters. The broad well-kept

streets in the town have had undue attention paid to them, to the

neglect of more remote thoroughfares. The bus stopped at various hotels,

the conductor arranging to deposit his passengers in the order which

suited his own convenience sooner than theirs. He took me a couple of

miles out of the way sooner than go round the corner at an earlier

stage. The reason was obvious—my hotel happened to be in the district

where the horses were stabled, and he left that for the last.

He had several passages

of arms with his fares, to which I listened with interest, as showing

the high point and fine shading that labour had reached in the Dominion.

Like everything else, it has the defect of its virtues.

“You must get down

here,” he said to a lady burdened with parcels and a valise; “the horses

can’t go up the hill.” The lady looked up with surprise, and replied

with great politeness, “A hill! There is no hill, gentleman! This is

So-and-so Street. I have parcels, gentleman, and it’s late.”

The “gentleman,”

nonplussed at this display of topographical erudition, banged the door,

and the omnibus went on.

RAILWAY AND TRAFFIC BRIDGE, SASKATCHEWAN

It was close on

midnight when I reached my destination. Rate of travel, three miles in

two hours!

Edmonton is situated on

the Saskatchewan River, well raised above its banks, and commanding an

imposing view. The population is nearly 25,000, almost double the total

of the 1906 census. It is the seat of government and the official place

of residence of the Lieutenant-Governor. The Alberta College has its

headquarters there, with 400 students attached. The educational system

is admirable. Large elementary schools have sprung up in a few years,

and a high school for advanced knowledge and university preparation. The

property is valued at over £100,000; all public requisites—water,

electric light, telephones and tramways — are municipalized. The system

of taxation makes no distinction between prairie land and land built

upon. A vacant lot is assessed at exactly the same valuation as one with

a five-storied building or factory on it. There is also a business tax

determined by floor space and nature of the industry.

There are twenty-four

churches, and twenty-one drinking saloons. The Secretary of the Board of

Trade, in commenting on this, said: “Churches are allowed an unlimited

margin of growth, but drinking saloons cannot be increased.” The

proportion in some of the provinces is one to a thousand of population.

The evidence of a great

coal industry is at once noticed on reaching Edmonton, in the blackened

track near the station, the elevated railway with its sidings, and the

inevitable row of coal wagons. The discovery of this mineral, which is

said to be a high-grade lignite, places the city in a unique position in

relation to the Dominion. So far it holds the monopoly of the trade. The

report of Government experts puts the area of the coal-bed at 11,000

square miles, and the quantity at 60,000,000 tons. The value of the find

to the inhabitants is most important, as the fuel can be purchased at

13½. per ton delivered, or ys. at the pit mouth.

Over 25,000 tons per

week are transmitted on the Canadian Northern Railway from the

Morinville mines, and the companies’ projected extension is planned to

traverse the Brazeau River valley, where further vast deposits of coal

have been discovered and only await railway facilities to become a cheap

and marketable commodity.

At the Board of Trade

offices I saw samples of various agricultural products, grown in

different parts of the province, which showed the versatility and

richness of the soil.

From Edmonton to

Calgary is another section of the Canadian Pacific Railway. It has been

opened up long enough for agricultural interests to take more definite

shape. Near Edmonton well-tilled farms are to be seen and herds of

cattle browsing on

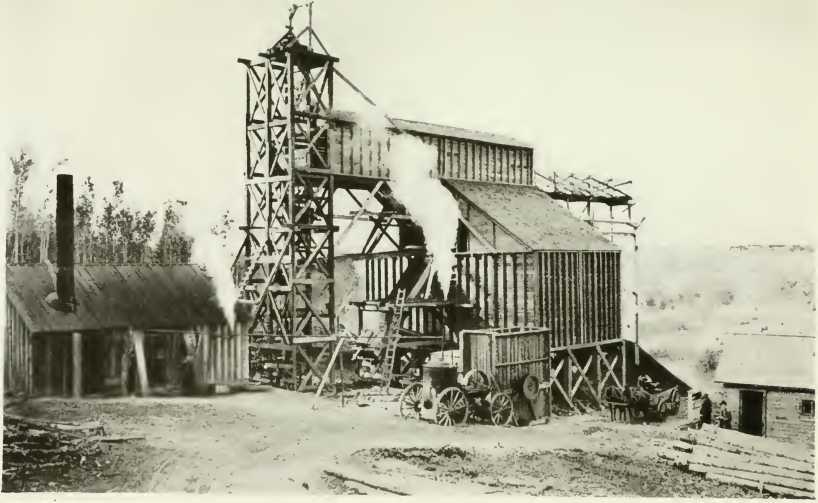

A COAL MINE AT EDMONTON

the pasture. It is a

section of the prairie, the severe flatness of which is broken by

undulating hills.

Flax is cultivated in

large quantities, which is used in the manufacture of oil cake and

ropes.

The ground was being

broken up for the winter wheat as I travelled along the line, and from

the train we could see the steam ploughs busy at work. The grain is

threshed in the field where it is reaped, and the straw in that locality

is burned, as it finds no market. In other parts of the agricultural

districts it has an economic use, and commands a good price. |