|

Through prairies to

Rockies—Portage le Prairie—Regina —Government offices and mounted

police—Climate—Growth of railways—Saskatchewan Province — Census returns

of industries — Moose Jaw — Alberta Province—Uncultivated

millions—Picturesque forests and streams—The home of the buffalo—Four

great rivers—Misconceptions of climate—The heat line—The “chinook”—Wild

grasses—Cattle rearing— Cereal productions—Exhibition medal awards—Wheat

returns —Clover—Sheep and wolves—Horse breeding—Champions at the World’s

Fair—Calgary—Democratic principles—Ranching and lumbering—The Bow and

Kananaskas Rivers.

JOURNEYING from

Winnipeg by the Canadian Pacific Railway, the great plain stretches to

the horizon. Its topographical features are varied by lakes and rivers,

but the general sense of flatness is so great that the traveller is

unconscious of the fact that in the first fifty miles there has been a

gradual ascent of 100 feet.

For many miles westward

Winnipeg leaves its impress on industrial life, repeating itself in

agriculture and commercial enterprise. At Portage le Prairie a busy

grain market is indicated by huge elevators and agricultural plant.

Mills and factories show activity in other branches of trade. At Brandon

there are large flour and planing mills, and a

THE SWAN RIVER

Dominion experimental

farm; it is a town of 13,000 inhabitants, in close touch with the

markets.

Hegina, the capital of

Saskatchewan, marks a further advance in trade and civilization, and is

a connecting link between the northern and southern portions of the

province. The Government offices are located there, and the

Lieutenant-Governor’s residence is a conspicuous building on the

right-hand side of the line. It Is in keeping with law and order that

the mounted police should be stationed in the same place. The Government

buildings are an imposing suite which cost £300,000.

Saskatchewan lies in

the same latitude as the British Isles. Owing to the influence of the

Gulf Stream our own climate is largely exempt from extremes.

Saskatchewan is of equable temperature, but for other reasons. It has a

dry, clear atmosphere owing to its elevation above the sea, and is free

from destructive storms. Summer heat averages about ninety degrees, but

the winter is cold and dry. Railway accommodation has kept pace with the

rapid growth of the settlements.

The province of

Saskatchewan covers nearly 230,000 square miles. The Northern division

is traversed by the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Railways. The

South-Eastern portion is an extension of the grain lands of Manitoba,

embracing the wheat plains of Regina and Moose Jaw. The part lying

between the Alberta boundary and Swift Current

and stretching to the

international boundary-line, is occupied chiefly by ranchers. It is

especially suited to the rearing of cattle on account of the abundance

of “buffalo grass.” This is a short herbage on which cattle can thrive

all the year without any other fodder. The Cypress Hills constitute a

sheltered area admirable for stock farming. What is known as the

“chinook” wind, which blows from the Pacific ocean across the Rockies,

prevails in that locality, and is advantageous.

Between the north and

south branches of the Saskatchewan River lie vast prairie lands, which

in due season are likely to yield extensive crops. So far it is only a

vast area of possibilities. Its soil is rich in the ingredients which

nourish wheat plants; the climate is dry, and there is an absence of

insect pests. Flax cultivation is very profitable, and crops can be

relied upon from the first year. One notices these all along the railway

track. In the great forest belt beyond the Qu’appelle River, there are

areas suited to the raising of live stock or mixed farming. In the

central division of the province, cattle and sheep require sheltering

for the winter months, and sheep succeed best in small flocks.

The official returns

indicate the growth of these and other industries. The Dominion census

for 1901 reports 217,053 cattle and in 1906, 472,854, an increase of

255,801 in five years ; 300,000 lbs. of wool are shipped every year.

There appears to have

been no diminution in the yields of crops from the time of the earliest

settlers. The soil is clay, covered with 18 inches of rich loam,

constituting an excellent bed for seed, and producing No. i hard wheat,

for which Western Canada is famous.

Regina is a rapidly

growing city and has a population of about 32,000 people.

Moose Jaw is 40 miles

beyond the Saskatchewan capital. The origin of the name is associated

with a legend of an enterprising wagoner who mended his cart with a

moose jaw-bone. It is rich in storehouses and stock-yards connected with

the grain-growing area. The growth of the population and the prosperity

of trade in this part of the province has resulted in the laying down of

a branch line which takes a north-westerly course to meet the

requirements of agriculture. The extension of this line to Lacombe in

Alberta is already projected. As an example of rapid growth, Mountain

Lake district in the vicinity may be cited. In 1901 its population was

256; in 1906 it grew to 23,553.

Alberta is one of the

two provinces that sprang out of the great plain lying between the

Rockies and the great lakes. In extent it is greater than Germany or

France, and Texas is the only one of the United States which exceeds it

in size. It lies in the same zone as northern and central Europe, and

its climate is similar to that of the countries within those latitudes.

During its short

existence, its wealth and population have made rapid strides, and it is

an example of young Canada growing with the advantages of the training

of the Mother Country, and applying the experience to the new

opportunity which the province affords.

Alberta contains over

160,000,000 acres of land, 100.000.000 of which are available for

settlement. In 1909 only one per cent, was under cultivation. It is a

vast undulating tableland, gently inclining towards east and north, and

picturesquely set out with forest, hills and streams. Everywhere there

are lovely lakes, yielding an abundant revenue of white fish. It was

once the feeding-ground of the countless herds of buffalo, which were

attracted to that region by the rich pastures. Alberta is well watered

by great rivers. The Saskatchewan, with eleven tributaries t which form

two branches, one irrigating the south, the other the north and central

plains. The Peace River and the Athabasca, two huge watercourses of the

Mackenzie basin, drain between them an area of 1.000.000 square miles.

The Hay River forms the quartette of this combined watershed.

The climate has been

depreciated, especially in English literature, by an erroneous notion

that a rich fur trade was associated with Arctic conditions, and that

Alberta, lying so far north, must be a region of ice and snow. When the

Canadian Government dispatched its explorers they discovered that the

habitat of the

fur-bearing animals was thousands of miles removed from the wheatfields

of Alberta. The heat during the summer is equally distributed throughout

the province. The rainfall takes place in May, June and July; and during

the harvesting months dry weather may be reckoned on unhesitatingly. It

is a common mistake to judge climate by latitude. Other forces

materially affect it. Wind currents from land and sea, and thousands of

square miles of high barren plains have a modifying effect over the

entire province as far as the Arctic Circle. The line of greatest heat

passes over Port Vermillion, 500 miles north of Edmonton, and 800 miles

from the States boundary-line.

The chinook, a

delightful breeze from the sea, is said to have a beneficial effect on

the crops. In proof of the friendly climatic conditions, the official

reports pointed out that the Indians lived for ages in these northern

regions, and pitched their wigwams on the banks of the Athabasca and

Saskatchewan, and wintered their horses on the unsheltered plains.

The North-West Mounted

Police, which were organized in 1874, and are intimately acquainted with

the province, confirm these reports. Two members of the force, whom I

met on my homeward journey, described it as the finest climate in the

Dominion. From the first of June to the first of August there are only

two hours of darkness in the twenty-four. Wild grass is so good that

there is no need to cultivate it. In the autumn, thousands of stacks may

be seen. There is no rain to spoil the making. A variety of blue grass

highly valued by cattle owners, grows in many districts, and the

well-known Kentucky species is said to flourish better there than in its

native soil.

The ingredients of the

land consist of marly clay of great depth, overlaid with rich black

absorbent soil, which chemical analysis has shown to possess all the

plant foods, with almost a complete absence of stones. The latter

feature greatly reduces the cost of breaking up the soil, and the steam

plough effects the process at a cost of 15J. to 25s. per acre. Cattle

grazing is carried on under favourable conditions, as there is no winter

slush, and the animals thrive and grow fat. In April the snow clears,

and spring opens, often with a breath of the chinook winds, which raises

the temperature almost to summer heat.

It is as a

cereal-producing province that Alberta is likely to be distinguished in

the future. The British Association meeting at Winnipeg, August, 1909,

pointed out that it is par excellence the wheat belt of the continent,

and just as other areas of the United States have become celebrated as

the corn belt of the continent, the provinces of the Canadian West will

become the great wheat-producers for the United States and Great

Britain. At the exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876, a medal was taken

for wheat grown 750 miles north of the international boundary

line; and at the

World’s Columbian Exhibition, 1893, the highest award was given for

wheat grown in the Peace River valley.

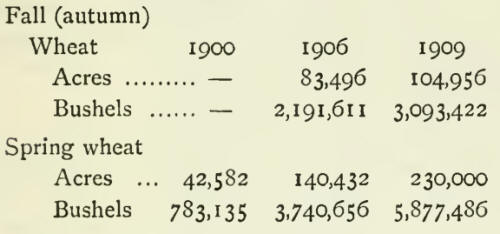

The following returns

show the progress made between 1900 and 1909 :—

Alberta also grows a

fine quality of oats. Fifty to sixty bushels an acre are a general

yield, sometimes running up to 100 bushels. Thirty-four pounds is the

standard weight for a bushel of oats. At the Provincial Seed Fair in

1909, a bushel weighing 50 lb. took the first prize. Alberta invaded

Paris, and took the highest award for oats at the last exhibition. The

increase in the production of this important cereal has been from

3,000,000 to 24,000,000 bushels in nine years.

The province yields two

or three different kinds of clover, which command a high price. The

timothy species yields from two to three tons an acre, and is sold at

from £2 10s. to £3. Alfalfa commands the highest price.

The fertility of the

soil, singularly enough, is attributed to the climate, which at one time

was regarded as inimical to agricultural interests. Prof. Macoun, of the

Canadian Geological Survey, points out that as long as the West is

blessed with winter frosts and summer rains, so long will teeming crops

be the product of her soil. The frosts help to crumble it; the rain and

sunshine do the rest. Artificial means of nourishing are unnecessary,

the grain entrusted to its keeping has eighteen inches to feed on.

It naturally follows

that the conditions that prevail in Alberta supply the best advantages

for the rearing of live-stock. The breaking up of the soil has also been

instrumental in disbanding the enormous herds of cattle belonging to the

old ranching days. Cattle-feeding on a smaller, and from the farmers’

point of view more efficient, scale is carried on as a remunerative

industry. The demand for home-grown beef is exceeding the supply.

Sheep are kept nearer

home, and are no longer the prey of the destructive coyote. A good

wolfhound or two are a sufficient provision against that. The reward

given by the Government for the wolfs head has tended to put a check on

the depredations of the thief.

Success in

horse-breeding has been marked of recent years. The heavy draught teams

seen in the towns and cities indicate this. At the Pan-American

Exhibition, and the New York Horse Show, the champion hackney came from

Calgary. At the

World’s Fair at St.

Louis in 1904, the champion stallion and mare were raised in Alberta.

From Calgary to

Saskatoon a new branch of the Canadian Northern Railway is about to be

opened. It traverses a tract of rich fertile prairie on which towns are

clustering with great rapidity. The laying down of rails and the growth

of towns follow as cause and effect. The traveller who found nothing but

the most primitive railway station on this newly-constructed track one

year, and passing the same way a year later, would fine a population of

one thousand people and all the bustle of a thriving town. This is

precisely the case of Kindersley.

Saskatoon, the starting

point of this branch, in 1903 consisted of 113 souls. In seven years it

developed into a population of 13,000, and possesses all the advantages

of a university, an agricultural college, and five schools.

From Swift Current to

Medicine Hat the Canadian Pacific line skirts hills rising to a

considerable altitude. The route leads through the valley of the South

Saskatchewan River. Fruit-farming, for which the district is

particularly adapted, is carried on there. The industry is fostered by

the Government, which works a model farm in the district. All along the

journey to Calgary the great plains hold the monopoly. Rivers, lakes,

and occasional distant rising slopes are passing incidents. It is

prairie, prairie, boundless prairie on both sides of the train for days.

Great plains roll away

before the eyes, untouched by human hand, unbroken by agricultural

implement, as virgin as when the primeval light fell on them. Here and

there a solitary homestead comes into sight, but the lonely pioneer of

civilization only emphasizes the awful sense of detachment. Herds of

cattle raise their startled heads in mute surprise at the invader.

Horses swish their long tails and with ears erect make ready for a

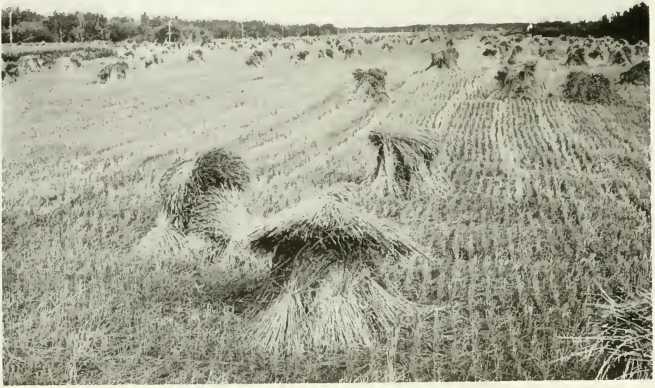

stampede. At intervals a golden cornfield flashes into sight, and a

wagon drawn by a team of horses, carts sheaves for threshing. A crow,

whose solitary habits were in keeping with the loneliness, idly flitted

across the scene. Of other signs of animal life there were few. Prairie

chickens found sufficient covering in the standing corn or sheaves to

hide themselves from view. Gophers, po-ta-chi-pin-gwa-si, “the thing

that blows up the loose earth,” as the Saltaux Indians call them, were

seen close to the railway cutting, reared on their hind legs and gazing

in curiosity, as if daily intercourse with the new order of things had

blunted their timidity. We were on the look-out for larger game, but saw

nothing but a badger, which dodged behind loose stones and soon

disappeared.

Calgary takes a place

second only to Winnipeg. It has a population of over 60,000, and has

progressed so far in democratic principles as to municipalize its

tram cars and electric

lighting. It is an active centre of ranching and lumbering.

The railway journey

takes the course of the Bow River, and a gradual ascent is made towards

the mountain region. The Kananaskas River mingles its waters with that

of the Bow a little further on, and the united force is concentrated in

the roar of the Kananaskas Falls.

This waterway is

drafted into service for purposes of irrigation as well as serving

Calgary for the transportation of its lumber. Through the Gap there is a

splendid view of the Bow River up-stream. The mountains on both sides

lean across as if they were about to form a natural rock bridge, but

stop abruptly as if they had suddenly changed their mind. A vulture

flitted between them as our train sped by. |