|

Prairie

conflagrations—Outposts of the Rockies—Drab flats and purple crags—In

the glacier track—Geological action— The Three Sisters—Between Canmore

and Bankhead—The National Park—Surviving specimens of big game—Rundle

Mountains—Minnewauka Lakes—Laggan—Lakes in the Clouds —The glacier

region and its rivers—Hector monument—The Kicking Horse River—A great

engineering feat—Douglas pines —Victims of forest fires—The Selkirks—The

track of the avalanche—The Eagle River—The Fraser and Thompson— The

Pacific—The flora of prairie and mountains—Vancouver— Shipping and

trading.

ALL along the railway

track a wide furrow is ploughed on both sides. Its object is to check

the spread of fire caused by sparks from the engine. Prairie

conflagrations are terrible scourges. Travelling between Calgary and

Edmonton on my return, the sky was clouded with the smoke of one that

must have been ten miles away. For hours we were within sight of it, the

air was laden with the smell of burning. With a strong wind it travels

at enormous pace, licking up everything in its way, and sending birds,

cattle and wild beasts before it in mad flight.

CANADIAN ROCKIES

It was early morning

when the outlying ranges of the Rocky Mountains came into view.

Gradually they broke upon us, as if adapting themselves to eyes too long

accustomed to uneventful flatness. Nature intensifies her effects by

contrasts. One thousand miles of flat are succeeded by one thousand

miles of mountain, but it is difficult for the insular mind to grasp the

meaning of it. Our familiarity with minute details is an indifferent

preparation for things so vast, and here we have the plains and hills of

England scaled up to the prairies and Rockies of British Columbia. Our

faculties are not equal to it. We can no more see in thousands of feet

than we can think in millions of figures—without practice. But nature

trains us in her own way. She satiates the eye with the drab of a

monotonous flat, in order to whet it for the purple of crags that “kiss

high Heaven.” And how cunningly she does it! In her hints, in foothills

coming at intervals with prairie lying between. First bare rocks, then

verdure-clad, followed by detached ranges, like stray notes and

introductory chords to full-souled music. The murmuring of rivers is

faintly caught in the distance to-day, which to-morrow will be heard in

full-throated roar. Pioneer mountains prove to be only links in ranges

which divide in clear-cut peaks amongst the clouds.

The solid stone and

timber of the railway line rests on nothing less than the track of an

ancient glacier which once crawled down the descent and discharged

itself in thundering avalanche as its fellows do to-day.

Geological action can

be clearly traced out in stratified rocks, some crushed beneath heavy

burdens, others leaning as if a touch would topple them over into the

abyss. In places deep ravines, in which mysterious shadows lurk,

penetrate their sides ; jagged crags, clean-cut and resplendent, crown

their summits. The Three Sisters between Bankhead and Canmore are a

conspicuous feature of rock formation. They stand equidistant, and rise

to an altitude of nearly 10,000 feet. The valley was putting on its

autumn tints when I saw them, and the young silver birch and poplar made

a golden pathway up to the skirts of the White Maidens, which looked as

if they had been just startled out of sleep. Hog’s-back ridges rose

between them, and a glacier river flowed at their feet. Between Canmore

and Bankhead there is a National Park, where surviving specimens of the

buffalo, once ubiquitous in the North-West, are to be found penned in,

and, like their original masters the North American Indians, shorn of

their wild romance. Bankhead is a favourite place to break the journey,

and exploration may be carried on amongst the Cascade and Rundle

Mountains, and Vermillion and Minnewauka Lakes. There is a comfortable

hotel there, equipped with all modern conveniences, where efficient

guides may be obtained.

Laggan is romantically

situated near the Lakes in the Clouds, marvellous insets of water high

up the mountain-side. Behind them, there is an extensive glacier region,

source of some of the great rivers which irrigate the valleys of British

Columbia. Verdure and fruitfulness spring up in their tracks. The

principal are the Mackenzie, rising in the Great Slave Lake, which flows

to the Arctic Ocean; the Saskatchewan, with its North and South

branches; and the Columbia, which empties itself into the Pacific, south

of Vancouver Island. The Valley of the Ten Peaks is one of the most

beautiful in this mountain district. The latter shape themselves into a

crescent round Lake Morine, rearing their heads in pairs, with great

snow-drifts lying between. The green tint of the glacier stands out

distinctly against the dazzling snow and dark mountain bases.

Further north a

monument is erected to the memory of Sir James Hector of the Palliser,

1858 Expedition, the first intrepid explorer of the Rockies. A more

imposing monument calls to mind his distinguished services, in the

colossal pile that bears the name of Mount Hector. The first president

of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, another celebrity, is honoured

in the name given to Mount Stephen, which is separated from the Hector

Range by a river. At this point the collective streams again separate

into two branches, the one taking the Pacific Ocean direction, the other

. Hudson Bay. A deep gorge of the Kicking Horse River is crossed where

Hector’s steed is said to have proved recalcitrant at the shock of the

ice water in fording the stream. The finest piece of railway engineering

of modern times has been accomplished at this juncture. The Canadian

Pacific train enters a tunnel 3200 feet long and begins a gradual climb

to a high level hundreds of feet above. It passes through a second

tunnel, 2910 feet, which pierces Wapiti Mountains, taking curves so

sharp that it is said an engine driver once pulled up before a red lamp,

which he afterwards discovered to be on the tail wagon of his own train.

Twice the Kicking Horse River is crossed, and when the highest ledge of

the spiral cutting is reached, four rows of railway track can be seen

rising in tiers above each other. The enterprise cost £300,000, the

price, by the way, of the whole pile of Government buildings at Calgary.

£50,000 were spent on explosives alone. The work was only completed in

1909.

When the line was first

constructed, there was a very steep declivity at this point, by no means

unattended with danger. Four engines were then needed to draw the train

; only two are required now. When descending, under the old arrangment

there was a series of side trackings, with switches for the purpose of

diverting the train when the driver lost control. These tracks branched

off the main line and slightly up-hill. On hearing the distress whistle

a man was ready to

switch off the train and so prevent a catastrophe which might be

terrible in its consequence. That danger is only a memory, and happily

few were aware of it at the time. Now the gradient is reduced from 4'S

to 2'2, and risks have practically disappeared.

From the high level

there is a wonderful sight of mountain valleys and yawning gorges. We

passed close to the tops of Douglas pines, which vie with the rocky

heights, and put forth all their strength to equal them in altitude.

Larch and spruce, in themselves magnificent, are dwarfed into

insignificance by their side. But everywhere amongst the dense forest,

solitary dead trees stand stripped of every vestige of foliage,

blackened and charred by destructive fires. There is a melancholy

desolation about them, but the thick undergrowth of their progeny wraps

them round, as if to hide their nakedness.

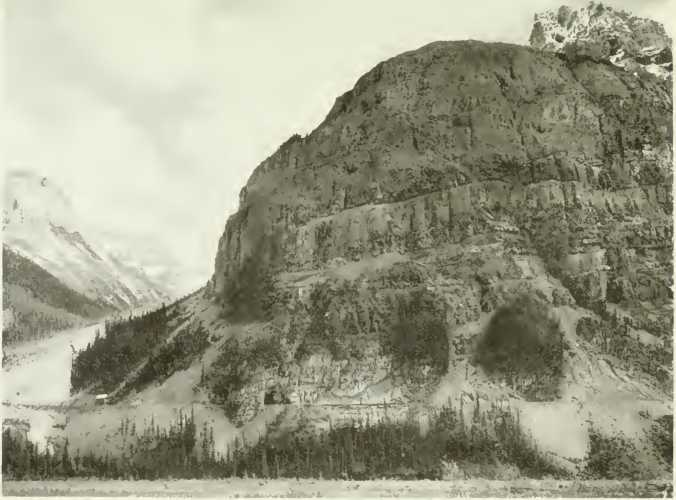

On the opposite side of

the gorge rise majestically the Selkirks, their glaciers so near that

the ice crystals dazzle. Deep in the mountain crevasses they are locked

fast, until higher temperature releases them, when they plunge down in

roaring avalanches that sweep everything out of the way. The deeply

scored cliffs show where ice slips have taken place, and the clear

passage where rocks and trees have been uprooted.

The railway cutting

again dips into the valley, and pursues its course along a narrow creek,

between Macdonald and Tupper mountains. So close is the line that they

rise in a sheer wall a mile high. Shelters are constructed at intervals

to break the fall of the snow. They are comprised of huge blocks of

timber, roofed over sufficiently to break up and divert the avalanche.

Without some such provision these slips would prove a serious obstacle

to locomotion, and trains would be constantly snowed up.

The river which the

line skirts, divides and unites as obstacles intervene or are removed.

The milky colour formed by the glacial silt sediment shows how much of

its volume comes from the ice regions. Picturesque cascades are formed

on the way, and foam-crested rapids, and now and again the roar of the

pent-up river amongst the rocks echoes from height to height. The Eagle

River divides into a number of branches, like the many pinions of the

birds wings, until through the wide-spreading valley it reaches Shuswap

Lake. The Thompson similarly grows into the Kamloops.

The moon was rising

over the water as we approached, and in the evening light gave an added

touch of romance to the peaceful scene. The Thompson River finds a new

setting in the famous canon through which it flows. The mountains mass

closer together, and their intimate features can be marked as the train

passes along the ledge.

The eye fastens on

colours rich and varied ; brilliant green far down the valley, red loam

streaking the banks, maple trees touched with premature autumn tints,

shimmering water, and all overarched by a deep blue cloudless sky.

The Fraser joins the

Thompson at the canon, which throws wider apart its rocky banks as if to

welcome the greatest of all the Columbian watersheds. The wear and tear

of long travel stains it, and the Thompson’s emerald tint is soon lost

in its muddy, surging currents. For miles the train and Fraser run pari

passu through Yale, Agassiz, and Harrison Mills to Westminster, where

the river lags, and slowly as a tired giant quietly sinks into the open

arms of the Pacific.

The great

transcontinental line terminates at Vancouver, which in itself only

marks a new starting-point for the shipping service to China, Japan,

Honolulu, Fiji, and many other ports in the far-off Orient.

The prairies, arid

though they appear, are not wanting in the adornment of floral life.

Even as the train rushes by, patches of buffalo plants and grass may be

seen. These are less abundant than when the buffalo trod the plains in

great herds. The stamping of their feet hardened the ground, which

together with manuring formed a more favourable environment. Near the

foothills the dwarf creeping plants and the wormwood are seen.

Among the canons and

timbered slopes, brilliant castilleias lift their crimson bracts in

adornment of the forest woodlands. High amongst the rocky crags Alpine

flowers grow; the yellow-eyed purple prunella, the deep violet phacelia,

a plant indigenous to the American soil.

Amongst the snow there

flourish the circular-leafed yellow buttercup and the white globe

flower, both of the crowfoot family. Amongst clusters of moss spring the

little blue forget-me-not, with Alpine penny cress and yellow Iceland

poppies. The flora of the Rocky Mountains, like its fauna, have much in

common with the Arctic regions. Professor Asa Gray identified 102

distinct Arctic region species, 81 allied species, and only 14 peculiar

to America.

Vancouver is one of the

most English towns in the Dominion. There vehicular traffic keeps to the

left, the rule in the Eastern provinces being the same as in the United

States and the European continent generally.

Mail steamers run from

its port to Nanaimo, San Francisco, and various ports on the coast. Its

returns give it a prominent place among great Western cities. In 1908

they reached £36,616.689. Property in 1909 was assessed at £14,800,000.

The shingles and lumber

trades and fisheries advertise themselves along the docks and railway

stations in the city and vicinity. Foundry and steel works are carried

on extensively. It is the centre of land speculation, and real estate

offices are numerous in every street. |