|

Game fish—Variableness

of the season—Primitive methods of angling—Salmon species—A thousand

miles’ swim—The conoe—The sockeye—The humpback—The dog salmon— Trout

species—The common trout—The steel-head—The Kamloops—The Great Lake

trout—The Dolly Varden—Brook trout—Distribution of salmon and

trout—Angling reaches— Death of salmon after spawning—Theories—Fly and

spoon bait—Fishing rods—The course of the Fraser River—The Coquihalla

and Hope rivers—Angling on the Harrison River— My Indian guide—Scepticism

and faith—A fight with a twenty-five pounder—The Harrison described—A

second captive— Invoking Adjidaumo—His blessing on a twenty-six pounder—

A visit to the Harrison Rapids—The conoe run.

GAME fish are plentiful

throughout British Columbia. The rivers and lakes vary in their seasons,

and a long and fruitless journey may be made by rail or canoe, only to

find that the visit is ill timed. Water good in the spring is worthless

in the autumn, and vice versa. A good deal of valuable time might be

saved if reliable information could be obtained on these points. I found

it extremely difficult to get any, as good anglers are by no means

plentiful in the province, and it is so vast that the information is

generally confined to a local, and therefore a circumscribed, area. The

primitive methods of angling that prevail in the Dominion generally are

a further obstacle in the way of hints that one angler is always ready

to give another. A man who is an expert with a hand line is not

necessarily an authority on rods and a trout’s taste in patterns of

Ephemeridse; an Indian skilled in the use of a spear does not constitute

a guide in the choice of favourite pools where the light impact of a fly

brings the sweep of the broad tail of a resting fish. Dynamite and dry

flies do not harmonize, and to such base uses one finds the magnificent

trout and salmon subjected in out-of-the-way places. Fortunately the

angling instinct serves in deciding where to fish, and it is often

superior to the kindly but ill-judged advice that one listens to

politely and prudently ignores.

There are five species

of salmon in British Columbia waters. The spring salmon, the cohoe, the

sockeye, the humpback and the dog salmon. So far only two out of the

five have been known to take any angling lure, and it is the general

opinion that only the spring salmon and the cohoe are game fish. The

former is widely distributed. It is known in California as the quinnat;

in Alaska as the tyee and king, and in Oregon as the chinook, or

Columbia. It is the Oncorhynchus tschawytscha of Walbaum, the

naturalist. From a commercial point of view the spring fish is regarded

as the most valuable of the salmon species. In shape it is short and

thick, with a small head of metallic lustre, growing sharp towards the

snout. The anal fin has 16 rays. There are 15 to 19 branchiostigals and

23 gill rakers. The tail is forked, with black spot markings, which also

cover the dorsal and adipose fins. The back has a bluish tint, becoming

silvery below the middle; the scales are very small, numbering 135 to

155 in the lateral line.

In spring its flesh is

red and rich, becoming paler as the spawning season approaches. As the

season advances the fish becomes so dark that it is called the black

salmon. It is said to run to 100 lbs. weight. One was caught with the

rod in the Campbell River in 1897 by Sir William Musgrave that weighed

70 lbs. There is a plaster cast of it in the Victoria Museum.

They run up the river

in spring and summer, travelling in some cases a distance of over a

thousand miles to the spawning beds on the far inland streams.

The cohoe (Oncorhynchus

alias Kisutch) is a much smaller species, running up to 10 lbs. weight.

It has 14 rays in the anal fin, 13 branchiostigals and 23 gill rakers.

It has 127 scales in the lateral line. It is a silvery fish, with

greenish-tinted back and iridescent hues when taken in the salt water.

In appearance it resembles the grilse of the European Salmo scilav. It

is small-headed and well shaped.

The sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus

narkd) weighs from 3 to 10 lbs. There are 14 rays in the anal fin, 14

branchiostigals, and 32 to 40 gill rakers.

The scales are small,

numbering from 130 to 140 in the lateral line. The tail is narrow and

well forked. The back is blue-tinted, running to silver below the

lateral line, giving the fish a handsome appearance. During the spring

season it undergoes a complete change in colour. Its sides grow carmine,

and the head and tail change to deep olive green.

The humpback {Oncorhynchus

gorbuscha) becomes hogbacked in the autumn to a degree of malformation

that accounts for its name. The scales are very small, 180 to 240 in the

lateral line. Black spots cover the back and fins. It has 15 rays in the

anal, 12 branchiostigals and 28 gill rakers. It has a bluish-tinted back

and is silvery beneath. It weighs from 3 to 6 lbs. It grows darker in

shade towards the back; the head is pointed, and the upper mandible

crooked like an old cock salmon.

The dog salmon (Oncorhynchus

ketd) is from 10 to 12 lbs.; 14 rays in the anal, 14 branchiostigals,

and 24 gill rakers. Its scales are much larger for its size than the

spring fish, 150 in lateral line. The head is longer but not so sharp.

When taken from the sea the dog salmon is a dark silvery tint with black

fins. In the river it turns dusky, and the sides grow red, the head

becomes distorted, and the front teeth grow large and dog-like in

appearance, which accounts for the name.

There are five or six

species of trout. Points of differentiation in some cases are so slight

that a distinct species is questionable. Taking the natural history as

we find it, the following is the classification: The common trout (Salmo

nay kiss). The steel-head {Salmo gardneri); the Kamloops {Salmo

Kamloops); the Great Lake trout (Cristvomer namaycush); the Dolly Varden

(Salvelinus agassizii); and the brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalus). The

steel-head is very like the European salmon. It is migratory and spawns

in the rivers, and like the latter returns to the sea. It runs up to 20

lbs. in weight. It frequents the mouths of rivers, but is also found in

lakes. In the Okanagan and Kootenay lakes the steel-head is said to

remain without returning to the sea.

The Kamloops trout is

classed as another species, but many naturalists confess to the

difficulty of differentiating it. Its scales are much smaller than those

of the steel-head, and it is marked with diminutive black spots almost

absent from the latter. The caudal fin is broad and forked, the dorsal

is set rather low on the back. Its tint is dark olive on the top, bright

silvery below the middle, with a broad light rose-coloured band. The

back is covered with pin-head black spots, becoming more numerous

posterially. The dorsal and caudal are thickly covered with these marks,

but few are found on the adipose, and the lower fins are quite plain.

The Great Lake trout is

spotted with grey, its body covered with thick skin. It runs to a large

size and averages 15 to 20 lbs. It is found in the great lakes from New

Brunswick to Vancouver. At certain seasons of the year it grows almost

black.

The Dolly Varden’s body

is slender, with a large head and broad snout. The caudal fin is

slightly forked, and its sides are an olive tint marked with round red

and orange spots. The back is similarly marked, but with smaller spots.

It is of the Chary genus.

The brook trout has a

large head; the pectoral and ventral fins are particularly elongated. It

is a dark olive colour with mottled or barred markings. It has red spots

on the side, and the dorsal and caudal fins are mottled with a darker

tint.

Salmon and trout are

widely distributed over British Columbia. The Fraser, Columbia,

Thompson, Kootenay and Skeena rivers are the main watercourses by which

the salmon ascend to their far-distant spawning beds. The tributaries of

these rivers are equally well stocked, and for sporting purposes are in

many ways superior to the main watersheds. An idea of the quantity of

the salmon may be gathered from the fact that the returns from the

industry amount to from £600,000 to £1,000,000 annually.

There are also

extensive lakes, such as Kootenay, Okanagan, Quesnel, Shuswap, Harrison

and innumerable minor basins, which form the habitat of fish.

From the angling point

of view, the lower reaches, the mouths of the small rivers, the creeks

and tideways, are the favourite places to obtain sport. When fish travel

a long distance inland they are becoming heavy with spawn, and the

deteriorating stage begins. If they take any lure then, there is no

fight in them, and as a sporting entity they are worthless. As a

comestible they are even less valuable.

Of the great shoals of

spring fish that press up fierce rapids and are battered against sharp

rocks, none are said to return alive. Ichthyologists find an analogy

between them and the Ephemeridae which die after they deposit their

eggs. The immense quantity that float down the rivers after the spawning

season gives plausible ground for this belief. The rivers are glutted

with dead fish, so much so that the effect in places is almost

pestilential. It is beyond doubt that a large proportion of the fish

perish, probably all that have travelled long distances—a thousand miles

for instance.

On the other hand, it

is impossible to say whether those spawning nearer the coast perish in

the same way. I saw excellent spawning ground below the rapids of

Harrison River, which is quite near the coast, and reasoning from

analogy there is little doubt that spring salmon spawn there. Salmo

salar of European waters survive spawning, and it is in keeping with the

fitness of things that British Columbian spring fish, which are larger

and stronger, should, apart from accident, also survive. It would be

interesting to ascertain whether the fish that choose the coast spawning

ground die like their more adventurous companions that make for the

heads of the rivers. The whole subject needs more careful investigation.

Mallock’s theory—that

salmon that have spawned are spotted on the gill covers, and in support

of which he gives corroborative if not conclusive data—might be easily

applied to the fish netted in the Fraser and other rivers. Mr. John

Pease Babcock, Provincial Commissioner of Fisheries in British Columbia,

in discussing the incredulity of Atlantic and European authorities, says

that they did not generally know that the Pacific salmon was not

identical with Salmo salar, which returns to the sea after depositing

its spawn. That statement scarcely disposes of the matter. The spring

fish caught in the rivers of the province up to 70 lbs. weight must, on

Mallock’s theory, be from 15 to 20 years old. It is difficult to

reconcile the fact of a fish going all those years without discharging

the natural function of its kind.

It may be laid down as

a general rule for angling purposes, that whenever there is a river

flowing into the sea, salmon will frequent it. As the British Columbian

coast extends 7000 miles, and the rivers are legion, the opportunities

for the indulgence of the rod are numerous. There are conditions,

however, essential to good sport, which must be borne in mind. Some

rivers, like the Fraser, are too highly coloured

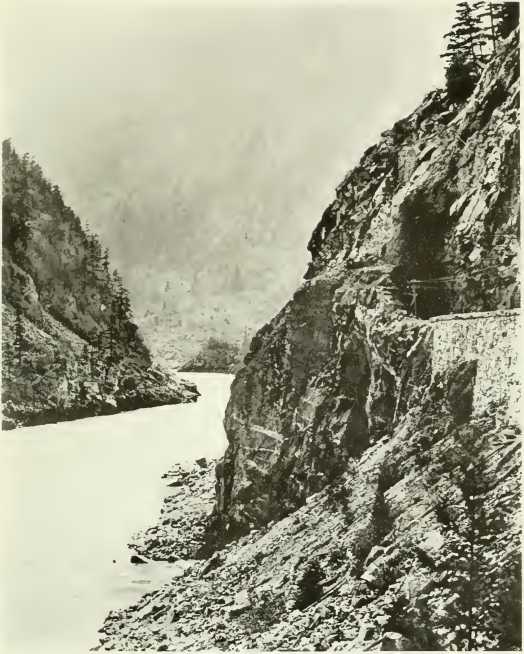

KRASER CANON

for the use of fly or

bait. A glance at the river from Lytton to Westminster gives

indisputable proof of this. The Canadian Pacific Railway keeps close to

it all the way, and at no point does the water grow clear, owing to

thick glacial deposits. The colouring makes it all the more prolific for

net fishing.

There are, however,

important tributaries which are clear and in good order for the

indulgence of the angling craft. The fish soon leave the main river and

press their way up these all along the coast.

I sailed up the Fraser

many miles, and although on the look-out for salmon, which were running

at the time, I saw none breaking the water. The moment we entered a

tributary where the water was clear they were to be seen rising all

round us.

Another condition to be

noted is the depth. The main rivers are very deep, especially when they

reach the low-lying valleys and are nearing the sea. Fly-fishing in such

places is out of the question. Salmon that take the fly are generally

found in pools in comparatively light water, where they rest for a day

or two on their long journey. It is on these the angler depends for

sport. The running fish rarely takes any lure. Among the boulders and

swirling eddies, one instinctively looks to find him. There sheltered

behind the big stones which break the force of the water, the fly is

likely to attract. Even spinning or trolling is not very profitable in

the great depths unless one happens to cross a resting fish.

In a clear river such

as the Galway in Ireland, where the movements of salmon can be studied,

a fly covers the quarry many times before he takes. He can be seen

raising his head as it crosses his resting-place, moving off a little

and returning to the same spot again, as if irritated by its

persistence, and at last shooting towards the top and seizing it.

The only bait that can

be seen in the deep Canadian rivers is a large spoon or minnow, which

sinks deeply and flashes vividly. The charge brought against the Pacific

salmon of not taking the fly should by rights be laid against the nature

of the river.

The best rod for the

purpose is a regular spinning or trolling pattern. It should be about u

feet long, and supple enough to control the movement of the fish without

breaking the tackle. A four-and-a-half-inch diameter check reel, capable

of holding from 120 to 150 yards of fine silk line is needed.

Green-heart, carefully tested, is suitable material, or the very best

built cane. Both of these I included in my outfit. I was also provided

with a 16-feet cane salmon fly rod, Hardy Bros.’ “Connemara” pattern,

and a Houghton 10-feet fly rod for trout, by the same makers.

The Fraser River flows

through the great Cariboo and Lillooet districts, into which several

broiling creeks empty themselves. Of these Alkali, Dog, Canoe, and Big

Bar creeks are the chief. Fish Lake, from which Canoe flows, is

suggestive of piscatorial

resources. North Fork

joins it above Lillooet, and Seton Lake and Cayoose River below it. The

ample volume of Kamloops Lake and River debouches into the Fraser at

Lytton, and there are numerous creeks between that and Keefer on the

Canadian Pacific Railway, such as Skuppa, and Neklipium.

Salmon River, below

Keefer, is a short spawning stream, but too far off the coast to hold

clean fish. The Coquihalla River at Hope is more promising, the distance

to the sea being under 70 miles. It is a fine sweep of water,

intersected with creeks, at the mouth of which there are good angling

pools. The principal tributary of the Fraser is undoubtedly the Harrison

River, 45 miles from the sea. At the rate which salmon travel it is only

about a day’s journey from Westminster.

The Harrison rises in

the lake of the same name, 6 miles from the Fraser. The lake itself is

about 25 miles long. It is fed by the Lillooet Lake and River.

I stumbled on the

Harrison on my way up the Fraser, and propos of the paucity of

information, no one seemed to know anything about its angling qualities.

It is as broad as the Thames at Hammersmith, beautifully wooded, with

peeps of mountain ranges, some of them snow clad. A steamer plies

between Chiliwack and Harrison Mills, passing through the Fraser Canon.

As soon as the boat

turned into the tributary, I noticed salmon breaking the water in

various places. Two Indians in a canoe were drawing a drift net, but the

boat rounded a promontory before they made a haul. There were local men

on board the steamer, belonging to Harrison Mills and Chiliwack, and I

made the round of them in the hope of obtaining information on the

angling. Trout could be got in the rapids, a few miles up the river, but

salmon would not take any lure. That was the sum of the information

obtained. I tried the captain, but drew another blank.

On landing at Harrison

Mills all aspirations to mount my rod and try my luck were discouraged

Nobody, it would seem, had cherished ambitions of the kind before. There

was an Indian settlement on the river, and I made my way towards it. A

squaw informed me in broken English that the “braves” were away

hop-picking. I explained my object, and was directed to a shack lower

down stream. There I found an Indian in the antepenultimate stage of

dressing, who bundled on a jacket, and came forward to answer my

questions.

“Any salmon fishing on

the river?” I asked.

“Yes, with a net,” he

replied, eyeing the rod in my hand, as constituting part of the

question.

“Won’t they take a

spoon-bait or fly? You see them rising,” I added hurriedly, noticing his

lips beginning to shape a “no”—but it came all the same.

“Why not?”

“These big fish take no

bait in this river,” came again the emphatic declaration. “We can net

some,” he said, as a concession to the disappointed shrug of my

shoulder.

“Look here,” I said, “I

have three hours before my train goes. Take me out for that time. I will

make it worth your while.”

“Yah, sure! but we’ll

catch no fish. How will that suit you?”

“Never mind, you won’t

lose anything by it.”

We started in a light

boat, and I mounted a 2-inch spoon, gilt on one side and silver on the

other, using a strong gut trace with a light sinker. Flies I judged out

of the question in such deep water.

Taking the centre of

the river, the Indian rowed me down-stream for a quarter of a mile. I

utilized the time in carefully noting the direction the fish were

taking. The centre, where the water was deepest, did not seem to be

their course so much as the sides, that nearest the right bank being the

favourite run. The current took that direction, and there were a good

many large rocks and other conditions favourable to the formation of

pools where the fish rested. The water on the left bank was weedy in

places, which indicated a slackness in the stream in that direction.

I trolled a short line

on the way down, but fishing with the current is never very successful.

The Indian, who evidently knew nothing about angling, possessed the next

best merit for my purpose—docility—and made himself a willing machine.

Up-stream I let out about sixty yards of line, and exhorted my guide to

row slowly. For half an hour nothing transpired, and I varied the

experiment by using a longer and at times a shorter line. Passing round

a rocky island there was a sudden convulsion imparted to the rod, and

the reel gave a vigorous shriek. I had hooked a fish. I awaited the rush

which generally follows when a salmon is hooked under such

circumstances, but it never came. Like a great many fish, my

introductory specimen unkindly severed his connexion at the earliest

possible moment. My guide looked incredulous, and fortified his unbelief

by the theory of a rock or weed.

We had not to wait very

long, however, for the triumph of a nobler faith. A hundred yards higher

up the river the reel again gave out signals of distress, and continued

to roar after I had accepted the gage of battle and used all the

resisting power of the rod. The fish made slightly down and across

stream. I applied all the brake I could with my finger, but the pace was

rapid, and the friction of the line nearly cut the skin. The usual wiles

of the playing fish were adopted in turn by my first Harrison River

captive. He rested after the run, giving me time to recover twenty or

thirty yards of line, filling in the interval with vigorous head-shaking

and jiggering. I directed my guide to row towards him. The pause on the

fish’s part was a brief one. The slack caused by the movement of the

boat stimulated his activities, and he dashed off again, not crying halt

until a distance of one hundred yards was covered. The rush brought him

to the surface, where he rolled over like a porpoise, showing a fine

broad side and a huge tail. The water divided before him with a hiss,

and a white-flaked surface marked the place where he floundered.

“After him!” I cried to

the Indian. A salmon like that, if he has a mind, can empty a reel.

Sharp as the line could be recovered, I wound it in. A fish that breaks

the water after a long run is generally tamed for a few moments, and

every angler knows how to take advantage of the pause. When next he

began to move, only about a length of a dozen yards separated us. He

headed up-stream, and doggedly resisted, keeping pace with the steady

strokes of the oar. I had met that kind of fish before; it is the usual

policy of the springer “to take it aisyjust to rest himself after racent

exertions.” The counter policy is to make the resting stage as hard as

possible; I bent the rod in pursuance of it.

“How long is this going

to last?” I wondered. I had not to wait long for the answer. He was only

sitting out a dance, and was at it again “like the divil,” as my Irish

gillie would say. Twenty minutes elapsed before there was any change in

the tune. Once more he turned down-stream, as if he was getting into

strange water and hankered after more familiar haunts. I encouraged him,

and the boat was brought round. Off he went, but saving his gills by

taking a slant—straight down-stream is drowning for a fish. Again I

called to the guide to be after him. The impassive countenance of

Hiawatha leaped into life, the spirit of the chase inbred in his blood

underwent a resurrection. The oars flashed. “Yah, sure!” he cried with

alacrity.

I tried to get below my

quarry, and so command the course, an old trick of toning down a fish

given to mad rushes, but he saw through it, and slanted off despite

vigorous pressure. A clear hour passed before there was any sign of

capitulation. Then the runs grew shorter, and I got him nearer to the

surface. I could see the fine proportions of the prize, and if he wanted

a little longer time, I was not going to hurry him.

Meanwhile, a telescopic

gaff in my game bag was placed in readiness. The grunt of surprise that

the Indian gave as he saw the fifteen inches drawn out to five feet, I

place amongst the interesting incidents of the day. At length, I got the

fish to the surface, and drawing him within reach of the steel, gaffed

him.

An hour and ten minutes

had passed from the time he drew the first screech from the reel. A

noble fish, perfectly fresh, and in magnificent condition. He scaled 25

lbs. exactly.

“You have forty minutes

yet to catch your train,” was Hiawatha’s comment.

“Are you good for the

day?” I asked.

“Yah, sure.”

“Then we shall spend it

on the river.”

We landed, and I

replenished my stock of tackle and laid in luncheon for the day. The

Indian suggested going higher up. There were plenty of fish everywhere,

but the river widened out so much that they were scattered. I had to

spend a couple of hours discovering the new lie. I did not think we

improved our angling prospects by the change, but making the best of it,

I watched the salmon, and discovered two or three distinct lines where

they were showing. The Indian’s sharp eyes were of great service in the

scouting business, and the way he brought the boat on them showed

considerable skill.

The Harrison above the

bridge takes a broad sweep, washing the base of a pine-clad mountain, a

favourite resort of bears.

Wild duck, feeding in a

bed of weeds, drew out of cover at our approach, and in well-ordered

file followed their leader into more remote shelter. A large

saddle-backed gull was settled on a narrow sandbank abreast of the

mountain. Far down the river the sunlight was streaming through a gap

between the hills, and lit up a patch of water with a brilliance that

made a more striking contrast with the dark^ background of forest pines.

Another fish soon

rewarded our vigilance. A good part of the morning performance was

repeated, but the item was got through more expeditiously. In forty

minutes the salmon was in the boat, and scaled 24 lbs.

We did nothing more

before luncheon, except to lose a spoon-bait which had proved the

attraction to the two fish landed. A good many uprooted trees and sunken

logs are scattered over the river, and one of them appropriated it.

Another spoon, but an inch longer, replaced it. It was a huge weapon, a

vulgar thing, inconsistent with the good taste of a well-bred salmon,

but it was “Hobson’s choice,” and up it went. The rise seemed to go off

between 1 and 3 o’clock, and I proposed returning to the lower reaches,

where so much time would not be wasted in getting on the fish.

We passed two or three

island rocks covered with blueberry bushes in full fruit, and had to

resist the temptation to tarry and eat. “I must get the third fish,” I

exclaimed to Hiawatha, as he gracefully plied the oars with scarcely a

splash. A loud clatter from a fir tree that overhung the bank called

attention to a squirrel. He shot up a great arm and, ensconced in the

fork, swished his tail over his head in an attitude of defiant security.

Ah, Adjidaumo, “Tail in air, the boys shall call you,” befriend us, as

thou didst the great Hiawatha. We too would catch the "king of fishes”;

and Adjidaumo swished his tail again, and gave us a send-off chatter.

The sharp prow of the

boat silently parted the water on either side, and clear of the wake of

the skiff the great spoon revolved, its blend of silver and gold sending

electric flashes through the river. It clears a shallow here, dips into

a deep pool lighting a space all round it. A Dolly Varden sees it and

sidles out of the way. A cohoe plucks up-courage, is about to make a

snap at it, hesitates for a moment, and it goes by. But higher

up-stream, in the shelter of a boulder, rests the modern Nahma, “king of

fishes.” His great tail sways to and fro, his head flicks from side to

side in swift glances at drifting twig and fallen leaf. His old

environment in the far-off sea, still and calm with the silver sand

beneath him, is forgotten, and he rises to the surface once more, and

breaks it in exuberance of life. A glimpse of metallic light is caught

as he slowly returns. He twists half round and instinctively stiffens

himself, simulating the lifelessness of a log. Nearer comes the rash

invader of the king’s territory, and swift as lightning there is a

plunge, and his great jaws close on it like a vice in a masterful grasp.

But the hidden sting of his captive smites him to the bone. “Ah, Nahma,

thou hast been rash in thine onslaught this time. Put forth thy best

strength now. Masterful as thou art, thou wilt need it. Biter that thou

hast been, truly art thou bitten!”

He is across the

stream, plunging and shaking his great head in mad resentment of such

unwonted infringement of his liberty. How mighty he is in battle, and

the decks must be cleared to snatch from him the victory; a jam in the

rings, a tangle in the reel, and he will smash like packthread the stout

silk line, or snap in sunder the most powerful rod!

In response to his

first plunge the reel gives. He mistakes the act of yielding for

weakness, and seeks to better the odds by increased pace and fiercer

battle. In the forty-mile swim from the sea there has been nothing in

the pace to match that sample. He rises for a moment, so close to the

boat that Hiawatha sees him, and exclaims, “Oh, if I had my spear!”

Shame on thee, Hiawatha! Think of thine ancestor who wrestled fairly

with the green corn until he mastered it. It is not thus we fight the

Nahma of the stream. Skill against strength is the principle; a fair

fight and no favour.

An hour goes by . . .

another half follows, and by this time the captive had traversed up and

down a mile of water. Now he lies on his broad sides, inert on the

surface. The hands of the watch marked five minutes past four when he

was hooked; it had reached ten minutes to six when he was gaffed. I was

almost unequal to the task of lifting him over the gunwale, and sank

with aching back and limp arms from the prolonged strain.

“You fish for the sport

of it,” said Hiawatha, in a final comment, as if a new vision of the

chase had stirred him.

Again there was a

chatter in the pine tree,

“Oh, my little friend,

the squirrel,

Bravely hast thou toiled to help me

Boys shall call you Adjidaumo.”

The fish weighed 26

lbs., a hen species, and, like the others, in the pink of condition.

These salmon are made

for fighting. They are short and thick and possessed of great muscular

power. If English anglers, who speak disparagingly of their powers

compared with the European species, would use lighter rods and tackle

than those generally employed on the Campbell and other rivers, I think

they would find a sporting entity in them in no respect inferior to

Scotch and Irish springers.

The capture of three

fish aggregating 75 lbs. created a little sensation amongst the

villagers, who assembled en masse to inspect them. Some of them looked

at the apparently frail rod and fine line and shook their heads in

incredulity. It seemed impossible that such tackle could hold out

against such odds.

The next morning the

proprietor of a large sawmill took me in his motor-launch up the rapids.

The fish passed through them on their way to Harrison Lake and the

Lillooet River, which constitutes their spawning ground. It is an ideal

place for the fly, delightful streams and swirling eddies, where a Jock

Scot or a silver doctor would soon give a tight line. It was impossible

to fish it from a motor-launch, and I had only two hours to spare before

catching the train which I gave up the previous morning.

The conoes run about

the time of the spring fish, and they are as ready for the fly as the

European grilse. I read in the Harrison River rapids the possibility of

the best salmon angling, and the application of the gentle art in its

most scientific form. |