|

Going west—Stave

River—Minnow and spoon-bait— Coquitlam River—Vancouver angling—Scarcity

of gillies—Off to the Narrows—Angling in the Pacific—Playing a salmon in

a swift tide—Dame Fortune’s amends—Off Vancouver Island— The Campbell

River—The Cowichan River—Advocacy of the fly—The best months—Trout

fishing—The fly season—The fry season—A visit to Seymour Creek—A lonely

forest—Track of the grizzly—In search of a trail—The Vedder river—A

charming retreat—Wading for Dolly Vardens—Capture with the fly—A magic

evening scene—The North Thompson River— The Columbia River—Kootenay and

Okanagan—The course of the Columbia River—Great trout lakes.

GOING further west,

between Mission Junction and Whomack on the Canadian Pacific Railway,

there is the Stave, another salmon river. It runs from Stave Lake, five

miles distant from Ruskin. The lake itself is only about three miles

long, and is fed by a triplet of small rivers flowing from the north.

Fraser salmon run up the Stave to spawn. It has many swift reaches,

where conoes and spring fish rest, and are in a mood to take the fly. If

the river is discoloured, a medium-sized spoon or a large Devon minnow

are suitable lures. The Fraser is beautifully flanked at Ruskin, with

hills well coated with thick brushwood. Lurking shadows play about their

shoulders, and over their summit the snow-clad heights of the Selkirk

Mountains flash and sparkle. A quail rises on the banks of the river,

and flies at a pace that gives this bird, almost extinct in England, a

valued place amongst American winged game. It slows off halfway across

the water, but the impetus has been so great that the wings do not flap

until it drops into cover on the opposite bank.

Coquitlam River is the

nearest of any importance to the sea, east of Westminster. It, too, is a

tributary of the Fraser, and flows from Coquitlam Lake, only a few

miles’ distance from the main river. Whilst it is scarcely equal to the

Stave or Harrison from an angling point of view, it holds a high place

amongst the sporting rivers of the province. The lure intended for the

smaller game is often taken by big fish, and a valuable addition is made

to the basket.

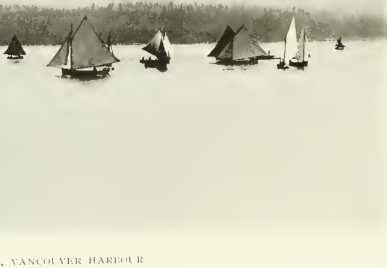

At Vancouver the salmon

angler again can mount his trolling rod and enjoy good sport in the

Narrows, where the Pacific sweeps in at full tide. There the peaceful

harbour, sheltered by mountain and forest, affords anchorage to the

great ocean steamers which sail to the Orient. -

The novelty of

rod-fishing for salmon in the open Pacific was so unique that I embarked

on the expedition with keen interest.

The difficulty in

Vancouver is to find a boatman to whom the destiny of the angler and the

fishing can be safely entrusted. It speaks well for the prosperity of

the city that there is practically none of the sporting leisure classes,

such as one finds in dumping quantity in Ireland and Scotland. There the

shoemaker’s last and the crofter’s hoe are willingly set aside for a day

with rod or gun. In Vancouver it is otherwise. One might spend a week in

quest of an efficient attendant, and fail to discover him. The makeshift

is a person to be studiously avoided. In desperation I picked up one,

who undertook to row me to the fishing ground, and to my horror I found

he was not acquainted with the elementary principles of rowing. The tide

had carried us out for about a mile without particular effort. When it

came to facing a cross-current his incompetence was so marked that I had

to take the oars myself and row to North Vancouver, where I dismissed

him and procured an Indian substitute.

I was fortunate,

however, on another occasion to find an Irishman who was taking a day's

holiday, and to whose qualifications as an excellent boatman was added

the ardour of an enthusiastic angler. In his hands I was perfectly safe,

and I cherish the most pleasant recollections of his skilful services.

On the first ebb of the

tide, we put off, skirting the shores of Vancouver Park, a piece of

virgin forest where the finest specimens of Douglas pines are still

preserved. The Narrows derive the name from the closing in of the

mountains on either side of the sea, leaving only a space of about half

a mile for traffic. A lighthouse is placed on the extreme land point on

one side, and the remains of a forest, intervening between the sea and

distant mountains, are on the other. The pent-up ocean flows in and out

at an enormous pace through the cutting. Three creeks join the sea at

the Narrows; the furthest west is Capilano, the next Lynn, and the third

Seymour.

The cohoe salmon run up

these creeks and hang about at the mouths during the summer-time

awaiting a spate.

Large spring fish are

found amongst them, but not in any number. The condition of the tide

determines the angling ground. With a spring ebb, the salmon come far in

and are caught between the lighthouse and Capilano Creek. As the tide

passes to the neap stage, one must go further out, and seek them off

Whitecliffe Point and the mouth of the Squamish River.

There is no difficulty,

however, in discovering their whereabouts. Cohoe are as lively as

grilse, and rise to the surface as freely. The first day I found them

off Capilano creek in shoals; a dozen at a time they sprang out of the

water. Unfortunately it was too deep to fish for them with a fly,

although up the creeks they take it freely. A spate is needed to put

these mountain torrents in condition, and during my stay they were

almost dry. There was nothing for it but to mount a spoon-bait. Cohoes

which do not average more than 7 lbs. prefer a small lure. Some anglers

embellish it with a red tassel a la pike mode, but I confined myself to

an unadorned pattern. The tide was at full ebb when we began to troll.

There was no need to be told which were the best places; the salmon

themselves soon indicated their whereabouts. Direct against the current

or across it yielded the best results. The fish feel the force of the

outgoing tide to a degree that makes them eschew its full strength, and

confine themselves to the edge on either side.

My first fish took the

spoon just on the margin, and fought as hard as any grilse that I have

caught, and my experience covers hundreds. He first kept to the slack

water, where he gave a couple of short runs and tried to divest himself

of the spoon by jiggering. This policy proved to be unavailing, and he

dashed off, and either by accident or malice prepe7ise got in the midst

of the current. The tide was running like a mill race—a mile a minute it

looked— and fifty yards of line were stripped off the reel before the

fish stopped. It is an old dodge of a salmon to get into a swift current

and stick there, swaying his broad tail from side to side. The worst

part of the business was the enormous quantity of driftwood that the

outflowing tide was carrying. I was in constant terror of getting my

line foul, a hundred yards of which were out at the time. At one moment

a huge log, fifteen to twenty feet long and thick in proportion, swept

right across the line. I held my breath and set my teeth in expectation

of calamity, but, marvellous to relate, it rolled over it without a

touch. It was time, however, to shift my quarry, and tightening up the

line and throwing the rod well back, I treated him to the Irish

discipline of “ giving the butt.” Gradually he came, and once on the

move I followed up the advantage until I had him in slack water. But the

dragging cost me the fish. He came close to the boat, near enough for us

to admire his broad sides and tail, when he quietly slipped off within a

few feet of the gaff.

Dame Fortune made

amends by giving me a brace, 6h lbs. and 4\ lbs., within the short time

at our disposal, beside which I hooked and lost a couple more. It is a

common experience to lose a large proportion of salmon on the

spoon-bait, particularly grilse, which cohoes resemble not only in

appearance, but in the softness of their mouths.

Off Vancouver Island

this kind of fishing can also be indulged. The open sea near the coast,

at the mouth of rivers and creeks, is prolific of salmon life, and fine

creels can be made. On the island some of the best known salmon angling

is to be obtained. The Campbell is the chief river, which yields record

fish annually. It rises in Buttles Lake, flows through upper Campbell

Lake, thence to Campbell Lake proper, and joins the sea above Willow

Point, opposite Cape Mudge, covering a distance of about forty-five

miles. The mouth of the river is the best place for fishing. Some angler

has yet to establish the possibility of alluring these big fish with a

fly. It is a misfortune that they are got so readily with a trolling

rod. Few anglers go to the trouble of applying more scientific methods

to their capture. The art of trolling requires no technical knowledge,

whilst the fly does; and only a small proportion of those who visit the

Campbell River are proficient in its use.

Next to the Campbell is

the Cowichan, which is easily reached from Victoria. It rises in

Cowitchen Lake, and flows through Duncan, falling into Cowitchen Harbour

about ten miles from its source. In its physical features it differs

from the Campbell, being swift and with abundant rapids suited to the

fly. The lake itself is good at the outlet, where a great many fish

gather.

July and August are the

best months for spring salmon on Vancouver Island. During September the

Campbell River ceases to yield heavy fish. The cohoes run freely during

that month, and can be caught in the Pacific and the creeks which

intersect the island along the coast.

It may be said of

salmon-angling generally, that its success is dependent upon the time

the fish run from the sea. It is then that they take a bait or rise to

the fly. Their sporting propensity wears off during their stay in the

river. I know, from long Q experience of Irish salmon fishing, that a

pool may be well stocked and not one out of a score will look at the

angler’s lure, the exception being the fresh arrival from the sea. It is

of the first importance, therefore, to obtain accurate particulars in

regard to the time the fish run. The omnibus information, that salmon

angling is good from July to November, is too general to be of value.

What we know is that the time varies on different rivers—some are early,

others late. This goes on from year to year without much change. The

danger is that one may travel hundreds of miles to a river and, on

reaching it, be as badly off as the man a hundred miles from anywhere

with the wrong cartridges.

Trout, on the other

hand, are permanent residents, and the angling season is more

indefinite. Here again a knowledge of their habits is valuable. When the

fly is on the water, is always the best time for angling. This rule is

of universal application. There is a set-off in many parts of the

Dominion against cultivating the acquaintance of the streams during that

period. It is the time when the pestilential black fly bites a piece out

of the angler’s flesh, sucks his blood, and then flies off with the

piece! Waiving that point, May and June are the best months. In July and

August the fry appear in the rivers and lakes in myriads, and receive

the trout’s undivided attention. This is the case at home, and I found

it exactly the same in the Dominion. When the fry appear the fly is at a

discount, minnows and spoons doing most of the execution. These spinning

lures imitate the habits of live bait, being bright and wriggling, which

trout and bass seize with avidity.

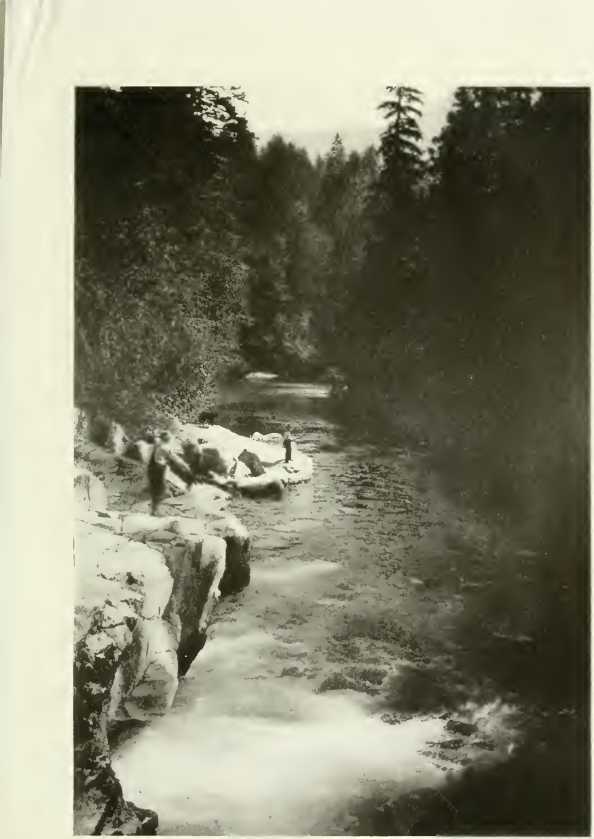

FISHING A VICTORIA CREEK

As far as my

observation went, there is very little fly on the rivers and lakes in

September.

There is a further

circumstance that is demoralizing to trout in Canadian waters. When the

salmon run up the rivers to spawn the trout follow them, intent on

devouring their ova, which are deposited on the gravel beds. So absorbed

are trout in this pursuit that they rarely look at any other food. They

are then freely caught with salmon roe, a poaching method of angling

that is most reprehensible. I fear it is widely practised in the

Dominion.

All the salmon rivers I

have mentioned hold trout. There are many others scattered all over the

province. The Cowichan in Vancouver Island is excellent, and very fine

specimens are taken in it. With a canoe, using a light rod and

medium-sized flies, good sport may be enjoyed. The creeks all round the

coast may be reckoned upon. During the flitting of the natural

Ephemeridae the best baskets are made. On .the mainland, near the city

of Vancouver, the creeks already referred to are favourite resorts for

the angling community.

The water was so very

low during my stay in that district that I was able to see the fish in

the deep pools.

Seymour Creek is a

swift river that flows through a cutting in the forest, and may be

described as a type of the streams that trout frequent. It is very deep,

and in some parts is so closed in that it can be heard but not seen.

From high banks its line can be traced for miles through the forest, a

black shadow by contrast with the green foliage and lichened rocks.

Other reaches are streaks of light, where the rapid water breaks into

sparkling crystals over log and boulder. The victims of the great forest

fire which, years ago, swept the district with disastrous effect, still

stand in charred magnificence. Black and dismantled Douglas pines rise

hundreds of feet, towering far above the living trees which, by

comparison, are insignificant. The solitude of the place was typified by

a lonely crow that rose and flitted before me, always choosing the stump

of a dead fir as its perch, as if its blackness and detachment were in

keeping with its mood. I followed a corduroy wagon road for some miles

in quest of the trail which led to the river. I could tell whether it

was leading to or from the creek by the crescendo or diminuendo of its

roar.

One human being only

crossed my path in the forest; he was armed and in quest of bears. He

showed me where one had been shot a few days before.

“Black bear?” I asked.

“No, a grizzly.” Of the trail I was searching for, he knew no more than

myself. I tried to force a way to the river by means of a steep

declivity, but, after scrambling down a hundred feet, I came upon a

ledge of rock and, on looking over, found myself on the summit of a

precipice which might have served for an eagle’s eyrie. I beat a

cautious retreat. It was the kind of place one not in search of a

grizzly might find him, and, being practically a cul de sac, might lead

to unpleasant consequences. Bears are not given to attacking except as

the easiest way of making their escape. Having nothing in the shape of a

weapon more formidable than a salmon gaff, I declined the risks.

One thing soon learned

in the forest and mountains is, that without a guide it is inadvisable

to leave the beaten track. At length I discovered the trail, which

proved a most difficult one. The way was blocked by fallen trees, abrupt

descents, and other impedimenta inimical to flesh and clothing. I was

compelled at one point to scramble over a charred log, which blackened

my nether garments beyond the point of defensible respectability. The

day had been exceedingly hot, and the mutterings of a thunderstorm could

be heard in the distance. When I got to the river I found it very low,

like Capilano and Lynn. The force of the current during spate could be

deciphered in the stones in the river’s bed. They were as smooth and

polished as pebbles on the seashore.

The only time to get

fish during low water was at dusk or break of day. I met an angler on

leaving Vancouver that had fished the creek that morning. He had taken

half a dozen good fish which looked to be from lb. to 4 lbs. weight.

They were all caught before sunrise. Similar results might be achieved

after sunset, so I was informed, but I had no mind for facing the forest

in the dark, as in Canada there is only a brief period of twilight.

Pursuing the journey

inland, there are many good trout rivers. The Coquitlam and Stave,

already mentioned as tributaries of the Fraser, fish well before the

salmon begin to run, and trout abandon themselves to the quest of spawn.

Another place that repays a visit is Lillooet River, flowing from

Lillooet Lake, and only a short journey from Stave. It amply rewards the

aspirations of the fly fisher.

Vedder River is about

six miles from Chiliwack, on the south side of the Fraser. It is

interesting not only from an angling, but from a scenic point of view.

It is exceedingly beautiful, and one of the most delightful retreats.

There is a hotel built on the river, and a new and more commodious

establishment is in prospect. The old one lost a considerable portion of

its frontage through floods, that are at times terrific. The river is a

sharp descent from Chiliwack Lake, only a few miles distant, and rises

and falls rapidly. A couple of winters ago, the wooden bridge that

spanned it, and the tennis court

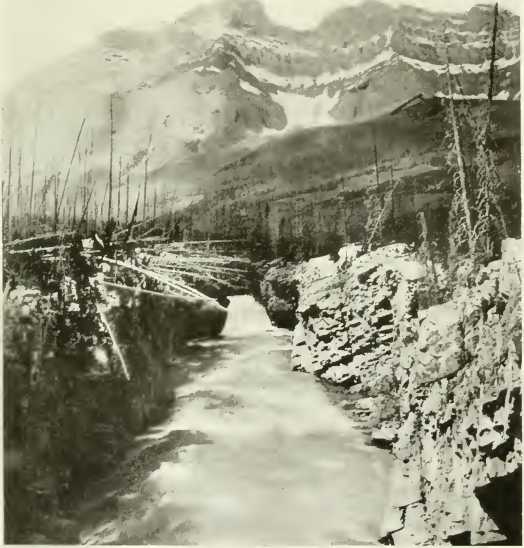

A MOUNTAIN CAXON, WHERE TROUT ABOUND

fronting the hotel,

Were washed away. The bridge has been replaced by an iron structure, and

a more elevated spot has been selected for the hotel. It is a convenient

centre for angling trips. The trout run to a large size; four to six

pounders are not uncommon. They are taken with small spoons or minnows.

Dolly Vardens are plentiful in the Vedder, which can be caught with the

fly up to I lb. or lb., and on a light rod and tackle they give lively

play.

It was my good fortune

to meet at Chiliwack a young architect from Vancouver who had graduated

in the English School of Angling. Both he and his wife were enthusiasts.

The latter, donning high rubber boots, defied the numerous fords, whilst

her husband and myself, equipped with waders, fished the deeper pools.

The river is intersected with tributaries, and the main stream separates

and unites many times in its precipitous course. Shallow noisy reaches,

followed by pools with a silence befitting their depth, and a cataract

here and there, are the conspicuous phases of the river. Where a March

brown or a Wickam fancy tripped over the gravelly shallow, the flash of

a Dolly Varden would appear, its blood-red and orange spots glinting in

the sunlight. Then the rod would quiver, and the chase down-stream

begin. The Vedder possesses all the exciting elements of sport—swift

rapids, swirling eddies, dangerous snags. A branch trailing in the

stream would invite sanctuary to the lively captive; how to steer him

clear and keep one’s balance was a problem painful enough at the moment,

but how delightful in retrospect!

Deep pools where we

knew the bigger fish lay were approached in a different fashion. There

was abundance of fry and minnows in the creeks. These we captured with a

dry fly, and mounted them on a Thames flight, the only method of

outwitting the wary game. My companion earlier in the week broke his

cast in a fish that must have been 6 lbs. The trout could be seen the

next day, springing out of the water, with the gut hanging from him,

apparently indifferent to this unusual appendage. Further up the creek

the forest trees, interlacing in thick impenetrable foliage, cast a cool

shade over the river, a vista of a magnificent range of mountains

amongst the glaciers, where the river rises, showing beyond. The peaks

stood clear-cut above the pine-clad woods, and in the evening light,

there stole that wonderful violet atmosphere that sheds such a

mysterious halo over God’s everlasting hills.

Of larger rivers there

are many, where the different species of trout are found. The North

Thompson, which joins the Fraser at Lytton, flows through Kamloops Lake.

Rising in the Quesnel region, and drawing its life from the union of a

small triplet of lakes, of which Albreda is chief, it winds in a

southern course, receiving the contents of other streams at various

points. Its water is clear, and most of the trout species make it their

habitat.

The Columbia River also

flows through the Quesnel northern district, south of Canoe River,

traversing hundreds of miles. Its course lies through Golden,

Windermere, East Kootenay and Nelson, an interminable stretch of water.

Kootenay and Okanagan

Rivers offer further angling facilities, as well as the Skeena and

Eagle.

The Great Lake trout

can be caught trolling, and battle royals can be had with fifteen and

twenty pounders in the Shuswap, Kootenay and Kamloops lakes. There the

formidable steel-head trout of the Salmonidai order is discovered, as

well as the larger specimens of the Salmo kamloops, or Dolly Varden.

These fish, like our European Salmo fario, affect cannibal habits on

reaching the years of discretion and scorn the fly. |