|

(Emerald Lake, the

Blaeberry and the Bow. Traverse of Mount Gordon)

“Snow-draped 'peaks

we passed by, and turquoise lakes set amidst the old pinewoods and

ringed round by gaunt precipices, and above} the snow. Wonderful

waterfalls that plunged sheer for hundreds of feet into rock-cut canyons

where the wild waters raged in fierce tumult. Sometimes the whole

undergrowth amidst the black stems of the burnt forest would be aglow

with the many coloured ‘painter’s brush/ or a mass of gold orange

daisies would have their colour set against the black satin stems of the

charred trunks and a sapphire blue sky. The lure of the wilds always

called us onward ”

J. Norman Collie

Emerald Lake is a Happy

Hunting-ground for the traveller who has not the time or the experience

for wandering far from the railroad. When the train comes down from Lake

Louise, across the Great Divide at the pass of Kicking Horse, and has

puffed through the spiral tunnels, below the peaks of Cathedral and

Stephen,1 with a glimpse of far-flung mountains in Yoho Valley; when you

have come to Field and been driven across the river and through that

glorious arcade of slender jack-pines to the Chalet beside the rippling,

green water, with a shining mountain-range beyond—then only have you

found the threshold of true contentment.

Perhaps as you came

over the Divide, at Kicking Horse summit, you noticed a small monument

at the water-parting. It is dedicated to the memory of Sir James Hector,

physician and explorer with the Palliser Expedition, sent out by the

British Government, in 1857, to explore the country for possible

railroad routes. The pass (5329 feet), was discovered by Dr. Hector in

1858, after he had set out from Bow Fort, crossed the Continental Divide

through Vermilion Pass, and reached the headwaters of the Kootenay.

Thence, he tells us, they traversed a height of land, and descended the

Beaverfoot to its mouth, “a large flat, where the wide valley

terminated, dividing into two branch valleys, one from the northwest and

the other to the southwest. Here we met a large stream, equal in size to

Bow River where we crossed it. The river descends the valley from the

northwest, and, on entering the wide valley of Beaverfoot River, turns

back on its course at a very sharp angle, receives that river as a

tributary, and flows off to the southwest through the other valley.”

Hereabouts occurred an

incident of near-tragedy. Hector goes on to state:1

“One of our pack-horses, to escape the fallen timber, plunged into the

stream, luckily where it formed an eddy, but the banks were so steep

that we had great difficulty in getting him out. In attempting to

recatch my own horse, which had strayed off while we were engaged with

the one in the river, he kicked me in the chest, but I had luckily got

close to him before he struck out, so that I did not get the full force

of the blow. However, it knocked me down and rendered me senseless for

some time. After travelling a mile along the left bank of the river from

the N. W., which because of the accident the men had named Kicking Horse

River, we crossed to the opposite side. We passed many small lakes, and

at last reached a small stream flowing to the east, and were again on

the Saskatchewan slope of the mountains.”

There is another

approach to Emerald Lake, quite as interesting and even more

spectacular. In a short hour one may motor from Field to the charming

bun-galow-camp at Takakkaw, stopping for a moment where the glacial Yoho

River makes a foaming junction with the Kicking Horse. You will know

when camp is near by the roar of water—Takakkaw Fall, coming from the

Daly glacier more than two thousand feet above. Winding and twisting in

an age-worn groove, it makes a little leap toward the brink of the

precipice and drops its plunging volume sheerly for a thousand feet,

arching outward again in a great curve of spray and falling five hundred

feet more to Yoho River. It is the highest waterfall in the Canadian

Rockies, and one may spend hours watching the play of colours on the

brilliant spray—the shimmering rainbows at the river’s edge, that cling

in the rising mist.

From Takakkaw, a

well-kept trail rises to Yoho Pass and leads down again to Emerald Lake

which is spread out below. If the day be still young, it is pleasant to

stroll about on higher levels—the height of Takakkaw becomes apparent,

and its glacial sources are in view. The Yoho Valley is revealed, with

peaks of the Continental Divide beyond—Balfour, Gordon, and all the

rest—mantled in the icefield of the Waputik. Across the basin containing

Emerald Lake, in the west, is the Presidential Range; its rising summits

and glacier-hung cliffs are constantly in view if one follows the trail

toward Burgess Pass. Mount Burgess is the rocky peak so conspicuous from

the lake shore, and flanks the low, wooded saddle which itself is right

above the Kicking Horse and Field village. To reach it, the trail leads

along the cliffs of Mount Wapta and affords splendid distant views into

the south, where rise the mountains of the Ottertail. It will perhaps be

late in the day and the sunset a thing to remember: the sun-flickering

gone from the lake and the green turned to a dull, filmy blue; the

cliffs of Burgess rosy with light; the Presidential Range a silhouette

against an orange sky. In the long shadows of gathering twilight, the

trail leads down to Field or toward the lighted windows of Emerald Lake

Chalet.

Immediately north of

Kicking Horse Pass, the Waputik Range continues the Continental Divide

to Howse Pass. Only a little of it is seen from Yoho Valley, but, in its

northern portion, the icefields mantling the range have a combined area

of more than forty square miles, draining chiefly to Bow River, a South

Saskatchewan headwater.

We ate our lunch in the

Yoho Valley, Howard Palmer and I, beside the river’s bank at Takakkaw.

It was July 4, 1922, and we walked the Burgess Pass trail back to Field

as a bit of training before leaving for prospective climbs in the

Freshfield Group. It was a calm, warm day, and we were not yet in the

best of condition; still we were down in the village in five hours and

thought well of ourselves.

While the entire body

of snow and ice is more or less continuous, it is arbitrarily divided

into two portions—the Waputik Icefield, extending along the crest of the

continental watershed from Bath Creek to Balfour Glacier; and the Wapta

Icefield, triangular in shape, continuing from Balfour and Yoho Glaciers

to Baker Glacier and other tongues at its northern apex.

At Field, we were

joined by our guide and friend, Edward Feuz, Jr., well known for his

many first-ascents in the Alps of Canada. Two days later found us on the

trail, our pack-train of seventeen horses being under the care of Jim

Simpson, who for more than twenty years has pioneered these mountains.

Bill Baptie was the horse-wrangler, and Tommy Frayne our cook.

Saddington—we never did learn his first name, as he answered always to

the nickname of “Mouse”—a youngster of fifteen, came along to wash

dishes and help keep the straying horses in line.

On the first day we

went only as far as Amiskwi2 River, tributary

to the Kicking Horse, through heavy timber, but on a good trail which

demanded no cutting. It is the beginning of the western approach to

Howse Pass, seldom travelled, but forming one of the few routes which

permit progress close in on the western slope of the main range. For the

most part, the steep British Columbia side with heavy undergrowth,

stimulated by the great precipitation on the western slope, serves as an

efficient barrier to travel with horses. We crossed Emerald and

Kiwetinok Creeks, with bits of steep work in their canyon beds; and from

our campground, in the evening, looked across the river to ridges and

rocky summits of the northern Van Horne Range.

It took us all the next

day to reach Amiskwi, or Baker, Pass. There are heavily timbered

stretches, where one rides for many minutes with no view save patches of

blue sky and slants of sunlight in the tree-tops; then a sharp descent

to a rushing stream: the horses splash through the milky glacial water,

and one catches a glimpse of snow-peaks far up the valley. Northland

trails are ever thrilling, with a prospect that changes constantly. We

gazed up at peaks bordering on Yoho Valley, and at the flying-buttresses

of Mount McArthur, so conspicuous for miles along. The forest is dense;

in places there are windfalls, the tree-trunks piled up and interlaced

like gigantic jackstraws. If they lie across the trail, packs may be

caught or snagged awry, and the axe comes into play. Jim would be off

his horse—he was in the lead—making the chips fly and the woods resound

with the echo of his chopping. The way is soon clear, the horses urged

into line—there is a trail vocabulary especially designed for wayward

cayuses—and the outfit swings along, with sunlight shafting down as

through clouds after a summer storm.

Amiskwi trail parallels

the western wall of the Waputiks; the pass (6535 feet) is not a useful

one for mountaineering as it is scarcely possible to penetrate the range

from this side. In the evening we ascended the high ridge east of the

pass—Ensign Station— whence we obtained a magnificent view of the entire

area. Across the deep valley of Trapper Creek, apparently impassable for

horses, we looked to the summit of Mount Baker (10,441 feet), and to

Mount Ayesha (10,026 feet), with its little blue lake high in a

rock-bowl. Mount Collie (10,315 feet) adjoins it closely and connects

its southern ridge by a glacier-saddle with the peak once named for the

German explorer Habel, but known since the war by the more cumbersome

title of Mount des Poilus. It is possible that climbers might cross to

the Collie-Habel col;5 but cliffs and timber would cause much delay if

horses were taken into Trapper Creek. To the west, we had vistas of

Mount Laussedat (10,035 feet) and the high peaks along Blaeberry River;

while, farther north, the southern walls of the Freshfield Group rose

grandly, tinged with the deep rose and purple shades that precede

twilight.

The descent from

Amiskwi Pass to the Blaeberry is over one of the steepest trails in the

mountains. For a short distance from the pass summit, one zigzags up a

side-hill of open woods whence an impressive view is had of Mount

Mummery, a white giant, rising across the valley into two splendid

peaks, above a curling green glacier cleft by dark morainal lines. Mount

Cairnes (10,120 feet), with its massive ice-crown, stands out

prominently in the southern Fresh-fields. Then comes the down-trail,

steep and muddy, slippery for beast and man, three thousand feet to the

river below. A black bear preceded us, and from his uneven, sprawling

track we concluded that he was in somewhat of a hurry; at least we never

caught up with him and our pace was by no means slow and dignified.

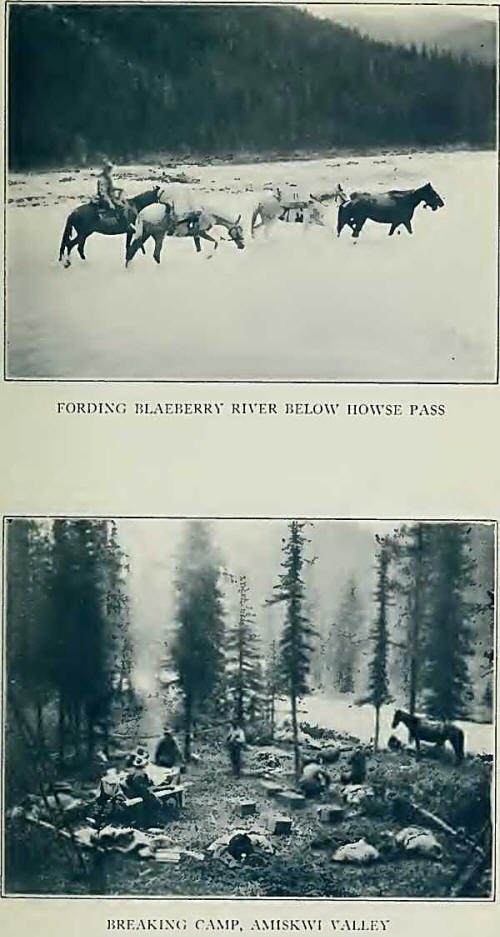

We forded the Blaeberry,

our long procession of horses trailing neck-deep through the water, and

camped in the meadows beyond. All afternoon, a second bear—perhaps a

neighbour of the Amiskwi traveller—wandered about our campground, and we

could see the tips of his ears above the scrub bush as he cautiously

raised up to investigate our presence. One of the boys chased him; he

clambered up to the top of a tall pine and sat disconsolately on a limb,

whimpering.

Our way to Howse Pass3

lay up the Blaeberry Valley, crossing and recrossing the diminishing

stream as we neared the summit. There are sharp little rocky peaks to be

seen at the head of Cairnes Creek, and a waterfall in a canyon farther

along. Much of the trail is washed out by the shifting river; what is

left becomes a tangle of undergrowth and obstructive timber, keeping Jim

out of his saddle and axes flashing. Camp was made below Mount Conway,

in a beautiful meadow not far from the pass summit, and we spent the

afternoon in making a visit to the cirque4

below Conway Glacier. On the very summit of Howse Pass a stop was made

to photograph a fat grey owl, that sat sleepily on the lowest limb of a

fire-killed tree and hissed at us when we reached toward him.

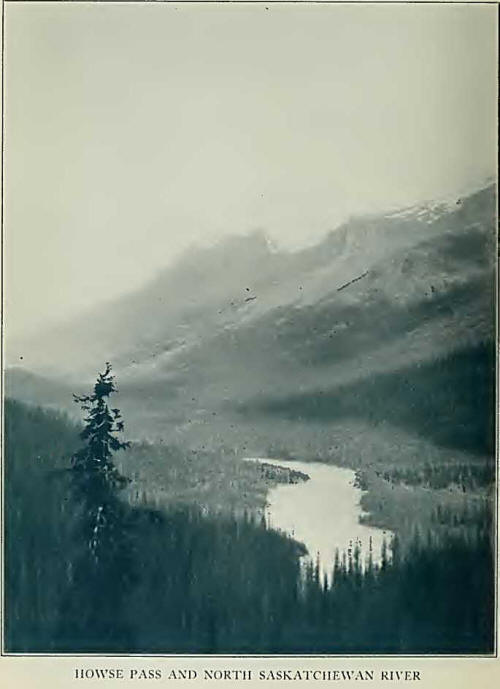

We were just at the

base of Howse Peak (10,800 feet), the highest of the Waputiks, a

serenely beautiful snow peak which had been in view as we came up the

Blaeberry and which flanks the pass on the eastern side. The range of

the Waputiks here diverges from the main watershed, and extends into

Alberta the peaks of Chephren—the western summit usually known as the

“White Pyramid”—Kaufmann, and Sarbach, which fill the Howse-Mistaya

river-angle. From the pass we ascended the timber cutting, marking the

Divide, through the forest for about a mile, and then spent a difficult

hour in the dense bush working out to the basin of Conway Creek above

the deep canyon into wrhich the stream descends. The basin is a large

one, extending into the heart of the Freshfield Group; a precipitous

hanging glacier cascades down from the north face of Conway, while the

main tongue curls over a terminal cliff several hundred feet in height

and sends down slender waterfalls to the cirque in which we stood.

Evening by the

campfire; crystal, with the last rays of sunshine back of the spire of

Mount Forbes. Summer evening is a long twilight, never growing dark, and

on this night a full moon rises, shedding its silvery glory over the

meadow. We can hear the distant jingle of bells as the horses move

slowly through the marsh-grass. The guides tell stories of old explorers

who passed this way in the long-ago; tales so fantastic that if the

shade of David Thompson or of Dr. Hector had walked in to listen, we

should have been unsurprised. If spirits return to haunt the best-loved

places may they not have joined us as invisible guests?

Next day was July 10th,

and we descended the canyon of Conway Creek to its junction with

Freshfield and Forbes Brooks; with many little fords, and fine glimpses

of the snowy Waputiks behind us. We emerged into a spacious amphitheatre

of joining streams, from which flows Howse River. A hotel would have

been here, had original plans matured and the railroad come this way;

but now there are only gravel-flats, with magenta fireweed, and game

tracks crossing and recrossing. South is the entrance to the Freshfield

Group, while westward, the massive outlines of Coronation Mountain, the

green saddle of Bush Pass, and the grim towering peak of Forbes,

complete a delightful and impressive panorama.

We were riding

leisurely along, admiring the beautiful prospect, when suddenly Jim,

ahead of me, began to urge his horse into full gallop. We followed

closely, and on a small gravel-cliff had the unusual experience of

catching a baby goat, that apparently had strayed from home. The little

animal was headed off by a horse on each side and a stream in front.

When several of us approached, the kid gave a frightened leap, fell in

the water and was rescued, kicking and struggling in the arms of Tommy.

It really was only coincidence that the cook should have made the catch,

but the wee beast no doubt expected immediate consignment to the pot. It

was interesting to see that the animal remained limp, as if dead, as

long as it was held tightly; but ready to stiffen like a steel spring

and bolt if the chance offered. We soon released it, and in our last

glimpse it was proceeding with all speed, but with a damp and injured

air, down the Saskatchewan gravel-bars.

As the Freshfield

Group, where we spent the days following, is described later,8 we shall

here continue on the Waputik trails. It was July 21st when we descended

Howse River to a point below the Glacier Lake stream. Alpine flora gives

the river-flats a gay appearance and game tracks are everywhere —moose,

bear, deer, and goat trails winding back and forth. Every evening we had

watched, through binoculars, the big billy-goats come out to feed on the

high alpland above the cliffs. And once, as we came late into camp, a

cow moose with her calf plunged back into the timber.

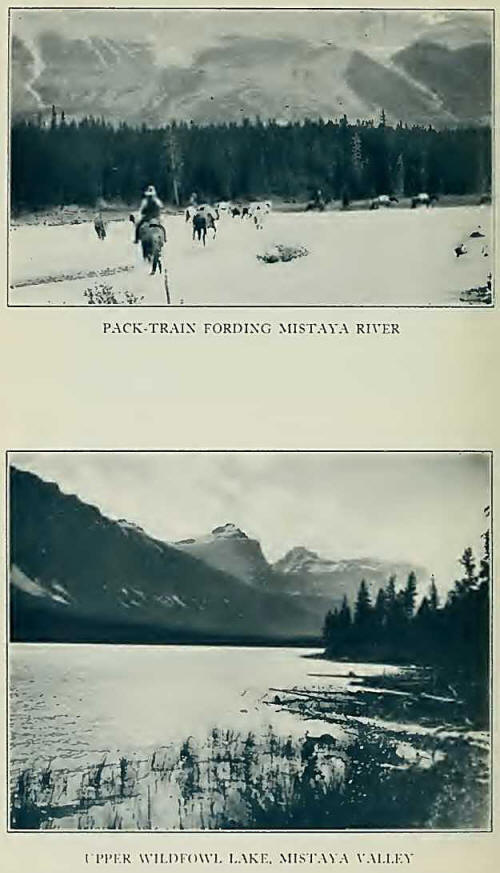

Since crossing the

Divide, at Howse Pass, we were again in Alberta. Next morning, rounding

the base of Mount Sarbach, we reached Mistaya5

River not far from the main Forks of the North Saskatchewan. It was a

chilly day, with fog and showers, one of the few on which we travelled

in the rain. A trail on the west bank of the stream avoids the old

difficult fords, and, at evening, camp was made at the base of Chephren.

Clearing weather cheered us, and we fairly revelled in the gorgeous

spectacle presented by the Kaufmann Peaks and the towers of Murchison,

all agleam with new snow, sparkling above the violet-tinted cliffs of a

shadowed valley.

The headwaters of the

North Saskatchewan— North Fork and Mistaya Rivers—parallel the

Continental Divide, in a broad, heavily-forested trench which continues,

across Bow Pass, to the upper Bow Valley, a South Saskatchewan

tributary. Perhaps nowhere else in the world can be found such a number

of large and beautiful lakes as those which are found here, directly

below the escarpment of a great mountain chain. Close to camp, the

Wildfowl Lakes reflect the rocky pinnacles that rise on the eastern side

of the Mistaya, and which give way to slightly lower and more separated

summits which buttress Bow Pass. Howse Peak and the Waputiks form a

stupendous, unbroken wall on the west. Trail to Bow Lake was followed on

the next day; a trail of gradual rise, with undulant, pine-crested

hillocks, whence one obtains glimpses into sequestered nooks, corners of

sapphire lakes, and occasionally, northward, the expanse of one of the

most extensive valley views of the Rockies— from Bow sources to peaks

near Nigel Pass and Bra-zeau headwaters. There are a few gaps in the

Waputik wall, through which we could see distant snowy peaks, beyond the

precipices of Mount Patterson (10,490 feet) with their slender,

interlocking icefalls.6 From the summit of Bow

Pass it is but a short walk to a rocky bluff above the ultramarine

expanse of Peyto Lake, with a view of the glacier and its ice-arch; one

follows the course of Mistaya River to the Saskatchewan Forks—spread out

like a map—with the snows of Mount Wilson visible beyond.

Bow Lake is the most

pleasant of camping places. Our tents were in a grove of old trees near

the water’s edge, where white-tailed deer came down to drink, heedless

of our presence. Just opposite, Bow icefall cascades downward through

the gap between Portal and St. Nicholas Peaks, the broken ice-snout

coming almost to the lake. Trout abound in the lake, big Dolly Varden,

but the larger ones always ruined our primitive tackle: a splash, a bit

of line flicking skyward on the end of a green pole, a man sitting down

with unexpected suddenness, and language usually reserved for private

conversation with the horses! Across the lake a wall of cliff, beginning

at Bow Peak, supports the Crowfoot Glacier; and, through a gap farther

east, the snow slopes of Mount Hector rise to a sharp peak.

The distance from Bow

Lake to the railroad, twenty-six miles, is broken by a camp on Hector

slide, north of which looms the jagged ridge of towers making up

Dolomite Peak. Down the valley one sees the peacock-blue water of Hector

Lake, and the delta made by the entering streams from the glaciers of

Balfour. And finally, through a rift in the clouds, the groups above

Lake Louise burst into view, Mount Temple and the Victoria ridge rising

above all the rest. The home-corral is near; the cayuses sense it, and

shy skittishly as the long-drawn whistle of a locomotive is heard far

down the valley.

From Bow Lake a year

later, in 1923, we reached rail by a decided variant of this route and

succeeded in annexing one more adventure of the Waputik trail. We had

come back from the Columbia Icefield, Dr. Ladd, Conrad Kain, and I, and

wished to avoid a repetition of the final day’s ride. So, deciding to

penetrate the mountain group and climb across to Takakkaw, we left the

horses, on July 24th, Simpson taking the pack-train by trail to Lake

Louise.

In an hour we had

rounded the lake to the gloomy canyon below the Bow icefall. So narrow

is the stream-cut gorge that not far from the glacier a single gigantic

stone forms a bridge, on which one may sit and look down into the

roaring cauldron of water below. Ascending the rocky ledges beside the

ice, we quickly gained height and eventually were able to cut our way

across the top of the fall to the Wapta neve.11 It presents a broad

expanse, somewhat crevassed, with long-ridged peaks rising from the

snow. Across the long slopes behind St. Nicholas and Olive we tramped,

to Vulture Col—its curious summit blocks suggesting an enormous bird

rising from a nest—and thence up the smooth, slanted slabs to the summit

of Mount Gordon.12 The weather was cloudless, but in the soft snow we

had taken nearly eight hours from our lake camp. From our elevation of

10,336 feet, we again paid our respects to old friends in the north,

from Freshfield to Columbia. Across the Balfour Glaciers we looked down

to Hector Lake, with cloud shadows moving lazily across; to the

Ottertail Group, and the peaks of Yoho.

We entertained the

audacious idea of going on to ascend Balfour, and actually started for

it; but a rumble of thunder, when we had glissaded to Balfour Pass,

warned us that we had accomplished enough for one day. Leaving Diableret

Glacier we ran down past

two lovely waterfalls

at the head of Waves Creek, the lower fall foaming and spraying through

a series of basins worn in the sandstone. We were not to go free. A

violent electric storm, with pelting hail, overtook us. The retreat of

Yoho Glacier makes it impossible to cross the ice-snout as in former

years. We made vain attempts to ford Yoho River; even when roped

together, the current was too swift for us. Conrad went clear under, and

came up looking like an alpine Neptune arising from the deep—still

holding his pipe between his teeth!

Finally we crossed the

canyon, lower down, making the passage roped, over a slanted log, with

serious damage to soaked clothing. Water rose and bridges went out. The

stream from Twin Falls, although one of the twins gave up the ghost some

years ago, was a raging torrent. We built a rickety structure from logs

and got over somehow; then wandered through the drenched brush to find

the trail, and finally arrived at Takakkaw as daylight was fading. A

last flash of lightning and a peal of thunder, resounding toward Little

Yoho, was as if Jupiter Pluvius and the witches of the Trolltinder were

having a final laugh at us. But we had defied these evil spirits and had

attained to knowledge of the fairy-like splendor of the Waputik. |