|

“The first travellers

called them the Glittering Mountains, on account of the infinite number

of immense rock crystals, which, they say, cover their surface, and

which, when they are not covered with snow, or in bare places,

reflect to an

immense distance the rays of the sun. The name Rocky Mountains was given

them, probably by later travellers, in consequence of the enormous

isolated rocks which they offer here and there to view.”

Gabriel Franchere

“The more elevated

portions are covered with perpetual snow, which contributes to give them

a luminous, and, at a great distance, even a brilliant appearance;

whence they derived, among some of the first discoverers, the name of

Shining mountains.”

Washington Irving

PREFACE

There is told, in the

Northwest, the story of an old prospector of whom, returning home after

many years, it was asked what he had to show as the equivalent of so

much lost time; and he answered only, “I have seen the Rocky Mountains.”

The desire to venture forth to the strange places of the earth is inborn

in most of us and we can quite understand the reply. Yet time and

opportunity seldom permit us to wander far from the beaten track.

Modern travellers,

however, due to increased transportation facilities, are at a distinct

advantage in comparison with the wanderers of a century ago, whose

journeys were made under conditions of great difficulty. Even fifty

years ago people were not found in the Rocky Mountains on pleasure bent.

In the opening of land areas, mountain ranges are things to be passed by

in the way most accessible; and not until a population becomes well

established does it begin to acquire the aesthetic sensibility which

enables it to devote a portion of its energy to the search after natural

beauty. This has been true of all highland countries—the Alps, the

Andes, the Himalaya, and the Rockies.

Thus, although travel

across the Rocky Mountains of Canada began more than a century and a

half ago, and the early fur-traders had considerable knowledge of the

passes and river routes, description of the upland valleys, the great

blue lakes, the vast icefields, has been reserved for wanderers of the

last three decades.

The Canadian portion of

the Rockies extends from the United States boundary at the 49th parallel

of Latitude, near the margins of Glacier National Park, to a point near

Latitude 54° where the 120th parallel of Longitude is crossed and the

range becomes sub-alpine. For more than four hundred miles it stretches

—a chain longer and less broken than the Continental Alps—and, in its

primeval state, who in a life-time can know it all?

Yet today many of us do

know something of it. For the tourist, passing through by rail, there

are splendid glimpses into the mountain land of Canada. Its margins are

accessible to everyone. Thousands of visitors have been to Emerald Lake

and the Yoho Valley; to Lake Louise and the Valley of the Ten Peaks; to

Banff and its delightful environs; and hosts of travellers, on a more

northerly route, are becoming acquainted with the vast wonderland of

Jasper Park. Engineers, however, being for the most part unimaginative

as far as scenery is concerned, put railroads through by the lowest and

easiest passes: natural beauty is incidental.

Hence it is that the

main chain of the Continental Divide, practically uncrossed by low

passes between the Canadian Pacific and the Canadian National Railroads,

is a land never seen by the casual tourist. It is true that the Howse

Pass and the Athabaska Pass were frequented in the days when the

fur-trade flourished, and were later thought of as suitable for rail

transportation routes; but, with the present locating of the roads,

these pass areas have returned to the oblivion of more than a century

ago.

Yet not quite. Alpine

wanderers, few in number to be sure, have come with their pack-trains,

have lingered a little while, and returned to tell of the marvelous

grandeur of new horizons. A few have told their story well. Others, due

to hardship and shortage of provisions, have come back with their goal

just beyond a bend. So if one be asked to compare the Rockies of Canada

with some other range, such as the Alps, it can only be said that we

know too little of them as a whole to place them fairly in apposition

with other mountainous regions.

If one realizes that

the things which characterize alpine areas are often found below the

snow-line, comparisons are not so difficult. In the Rockies of Canada

one seeks in vain for cattle herds, chalets, or funiculars; and in their

stead are found the pack-train, a bed of pine-boughs under an open sky,

and old trails of the Indians. And so this book is written to tell you

of the things beyond the margins; of natural wonders which will be the

heritage of coming generations. In the light of more accurate

topographical knowledge and established nomenclature, it seems not out

of place that a new volume should be added to the small list dealing

with mountaineering and exploration in the Canadian Rockies.

The author, with but

few intermissions during the past decade, has been actively interested

in the peaks and icefields at the sources of the Saskatchewan and

Athabaska Rivers. It is his desire to place on record the results of

three major expeditions into the mountain area of the Continental Divide

between the Canadian Pacific and the Canadian National Railroads,

together with less strenuous excursions among some of the beauty spots

which every trans-Canadian traveller should see. In this way it is hoped

that a volume will have been produced alike of interest to the leisurely

excursionist and to the more strenuous climber of peaks.

The Expeditions of 1922

and 1923 were undertaken for the purpose of investigating the icefields

and peaks at the headwaters of the North Saskatchewan River.

In 1922 the Freshfield

Icefield was visited and its highest peak, Mount Barnard, with a number

of others, ascended for the first time. A preliminary study of the

motion in the Freshfield Glacier was undertaken at this time. During

this season the upper Blaeberry, Howse, Mistaya, and upper Bow Valleys

were traversed.

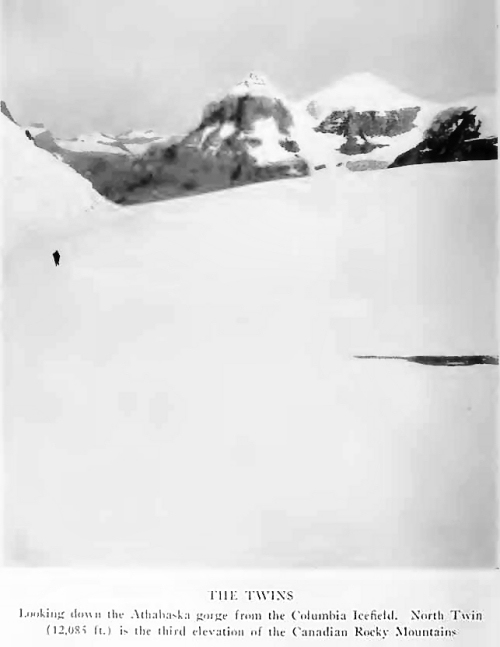

In 1923 the author

visited the remaining icefield sources of the North Saskatchewan along

the Continental Divide. Alexandra River, the old “West Branch,” was

followed to its sources, and a base camp made on the margin of the great

Columbia Icefield, Canada’s tri-oceanic divide. The mountaineering

results were of importance and extensive data regarding the details of

the icefield were secured. The icefield was twice crossed, from

Saskatchewan to Athabaska sources. First-ascents were obtained of

formidable Mount Saskatchewan, and of North Twin; the latter, 12,085

feet in elevation, being the third of triangulated heights in the

Canadian Rocky Mountains. Mount Columbia, 12,294 feet, the second

elevation of the range, was climbed for the second time. With horses a

remarkable crossing was made, by way of the Saskatchewan Glacier, from

the head of the “West Branch” to the sources of the Sunwapta; and, from

below Wilcox Pass, Mount Athabaska was ascended.

The Expedition of 1924

deals with a more northerly section of the Continental Divide, situated

at Athabaska River sources—the historic location of the earliest

mountaineering in Canada. The narrative extends to the Mount Robson

area, where the author had previously camped in years before the

appearance of the “modern conveniences” that now exist.

This then is a book of

mountaineering, not presenting the Canadian Rockies in their entirety—no

single volume will ever do that—but including many of the finest things.

It is also a book of mountain travel, under conditions such as perhaps

the European traveller experienced in the Alps during the Eighteenth

Century. Finally it is a book of mountain history; for here is Geography

in the making, and with a tradition behind it—a story that has never

been properly gathered together, and whose details, in part at least,

are gone forever.

While our own

performances have been thought worthy of the printed page, they can

never mean to the reader quite what they mean to those who took part in

them. You must go yourself to comprehend the daft enthusiasm which

follows such a journey. No one but ourselves can ever be identified with

those days of crag and precipice; of ice and snow in sunshine and storm;

those days with the pack-train winding along northern trails; those

nights—starlit nights in the country of fur-trade routes—with song and

story beside the campfire. Those things are ours forever, while life

lasts. Our guide, Conrad, and he is a philosopher, used to say, “It is

good to have been once young, if only you have happy memories.” A modern

writer has paraphrased the thought in saying, “Memories are given us

that we may have roses in December.”

This is the record of

our mountain memories, which may perhaps have the power of shedding

afterglow, even though the light be dim in comparison to realities. And

yet, if you glimpse but a bit of it, great indeed will be our reward.

A great deal of

painstaking research was required in collecting the early historical

material for the present volume, but as far as possible every

source-book has been examined. The old narratives are exceedingly rare,

and not to be had in every library. For this reason they have been more

fully quoted than otherwise, in order that they may afford an available

authentic record of events occurring within the mountain area before the

advent of modern travellers.

A certain amount of

topographical material has been inserted, and those who care to follow

it in detail should secure the Atlas of the Alberta and British Columbia

Boundary, Part II, containing maps which will be of service. The Atlas

may be obtained from the Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of

the Interior, Ottawa.

Not all that follows

makes its appearance for the first time;1 but the outlines of several

chapters, pub-ished in the Alpine Journal, the Bulletin of the

Geographical Society of Philadelphia, the Canadian Alpine Journal, and

elsewhere, have been largely rewritten, amplified, and moulded to

conform to a progressing narrative.

Acknowledgement is due

to the many who, by their favors and suggestions, have made this book

possible. The Topographical Survey of Canada, comprising a group of

gentlemen most cordial, has allowed the use of a selection of

photographs obtained during the fieldwork of the Interprovincial

Boundary Commission. The Smithsonian Institution has agreed to the

reprinting of Mr. Palmer’s paper on the Freshfield Glacier. Messrs.

Osgood Field, Val. A. Fynn, Wm. S. Ladd, Howard Palmer, Harry Pollard

and Max Strumia have permitted the use of photographs. Dr. James A.

Morgan, of Honolulu, has kindly secured for me a photograph of Douglas’

Tombstone. The editors of the Alpine Journal, Appalachia, and the

Canadian Alpine Journal have loaned a number of the engraved blocks.

During 1922 and 1923,

the pack-trains were in charge of James Simpson, a pioneer and hunter of

wide experience, a powerful mountaineer, a man of resource and

initiative, and withal, a true friend; to whom, in company with Conrad

Kain and Edward Feuz—the leaders of the mountaineering—the author has

taken pleasure in dedicating this book.

J. M. T.

2031 Chestnut Street Philadelphia, Pa. December, 1925

CONTENTS

Chapter I. Lake Louise:

The Entrance to the Northland.

Chapter II. Trails of the Waputik.

Chapter III. The Freshfield Group.

Chapter IV. The Mountains of the Alexandra Angle.

Chapter V. The Ascent of North Twin.

Chapter VI. Mount Saskatchewan and Mount Columbia.

Chapter VII. Passage of the Saskatchewan Glacier.

Chapter VIII. Athabaska Pass and the Voyageurs, 1811-1827.

Chapter IX. Athabaska Pass and the Voyageurs, 1846-1872.

Chapter X. Nineteenth Century Speculation in Regard to Altitude at Athabaska Pass.

Chapter XI. The Mountains of the Whirlpool.

Chapter XII. Climbs from the Scott Glacier.

Chapter XIII. The Ramparts and Mount Fraser.

Chapter XIV. In the Shadow of Mount Robson.

Chapter XV. Trail’s End.

Appendix A. Summary of Ascents, Between Kicking Horse and Robson Passes,

1922-24.

Appendix B. Summarized Itinerary of Expeditions, 1922-24.

Appendix C. A List of Some of the Loftiest Triangulated Peaks of the

Rocky Mountains of Canada.

Appendix D. The Freshfield Glacier, Canadian Rockies (by How and

Palmer).

Appendix E. David Thompson and the First Crossing of Howse Pass.

Appendix F. The Panorama from Mount Columbia.

Appendix G. A Note on the Original Journals of David Douglas. |