|

“Our course lay, for

the most part, over vast fields of snow, but the early portion of it

presented scenery of surpassing beauty, far more magnificent and

dazzling than that of the day before. There were broad and bridgeless

chasms, whose depths the eye, from their dizzy edges, vainly sought to

ascertain;—towering masses, in forms that, from their strangeness,

seemed unreal;—spires of brightness, grottos and palaces of frost,—here

recent, soft, of snowy whiteness,—there older, hardened, passing into

crystal azure,—sprinkled with frozen dew, festooned with silver fringe;

their inmost caverns dark,—vast stalactites of ice, in line, guarding

the portals.”

Dr. Martin Barry

The Continent of North

America possesses two hydrographic apices which are remarkable for the

river systems extending therefrom. In each of these areas occurs a

watershed of the triple-divide type whose streams form great and lengthy

rivers, flowing enormous distances to terminate in widely separated

bodies of water.

The southerly of these

interesting regions is found, near Latitude 43°, in the Wind River

Mountains of Wyoming, south of Yellowstone National Park. Here rises the

Snake River, flowing to the Columbia, its waters carried through British

Columbia and emptying into the Pacific at the northwest corner of

Oregon. Not many miles distant are sources of Green River, flowing

southwest to the Colorado and reaching the Gulf of California. Eastward,

branching headwaters of the Missouri find their way to the Mississippi

basin and the far-off Gulf of Mexico.

Less well known is the

Canadian watershed to be found in Latitude 52°. There, in a region

extensively glaciated, are sources of river systems whose waters make

their way for hundreds of miles, by winding, devious routes to three

separate oceans.

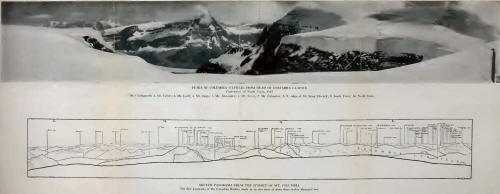

The Rocky Mountains of

Canada form the Alberta-British Columbia Boundary and extend northward,

from the Montana line, at the 114th Parallel, until the 120th Parallel

is reached, near Latitude 54°, and

the range becomes

subalpine. Great icefields mantle the Continental Divide between the

Canadian Pacific and the Canadian National Railroads, the scenic

grandeur culminating in the Columbia Icefield, in Latitude 52° 12'.

This icefield, the

largest known in Canada, containing approximately one hundred and fifty

square miles, forms an unusually compact triple-divide. From its snows,

on the Continental Divide, attaining an elevation of 10,000 feet over a

large area, are formed the headwaters of the Athabaska, which, by way of

Great Slave Lake, joins the Mackenzie system whose delta is beyond the

Arctic Circle. Western ice-tongues supply Bush River, tributary to the

Columbia and reaching the Pacific. From many converging streams on the

eastern slope is formed the Saskatchewan River, emptying into Lake

Winnipeg whence the Nelson River continues the drainage to Hudson Bay

and the North Atlantic.

Thus do two mountain

uplifts form the drainage sources for much of Continental America

between Mexico and Alaska.

The two water-partings

possess no little of historic interest. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark

Expedition, reaching the forks of the Missouri, pioneered the Jefferson

River and crossed to the Clearwater branch of the Columbia on their way

to the Pacific Coast. Only a little later, Canadian fur-traders, in

1807, made use of the Howse Pass in travelling across the Rocky

Mountains, from the North Saskatchewan—the Kootenay Plain—to the

Columbia Valley. In 1811, the Athabaska Pass was opened by David

Thompson of the North-West Company and served for many years as a

much-frequented route between Athabaska trading posts—Fort Edmonton,

Henry House, and Jasper House—and the Columbia Loop.

Anyone who has even

superficially examined the map of a Continent, will realize that rivers

of any length possess sources in elevated portions of the earth’s

surface. It is the land uplift, usually a mountain region, in which

occurs the greatest precipitation; the ranges and inland table-lands, or

even lofty plateaus, serve the further purpose of providing the

potential energy, the vis a tergo, for stream flow. It will be further

understood that such a region is topographically more complex than an

area of coastal plain; and that, to unravel the complex features which a

mountain range often possesses and which are frequently hidden, it is

quite essential for a field observer to attain lofty ridges—if not the

very summits themselves—in order to discover what may lie beyond.

The Columbia Icefield,

one of the largest subarctic fields, was first seen, in 1898, by J.

Norman Collie,1 who described the view from the

summit of Mount Athabaska, as follows: “A new world was spread at our

feet; to the westward stretched a vast ice-field probably never before

seen by human eye, and surrounded by entirely unknown, unnamed, and

unclimbed peaks. From its vast expanse of snows the Saskatchewan Glacier

takes its rise, and it also supplies the head-waters of the Athabaska;

while far away to the west, bending over in those unknown valleys

glowing with the evening light, the level snows stretched, finally to

melt and flow down more than one channel into the Columbia River, and

thence to the Pacific Ocean. Beyond the Saskatchewan Glacier to the

south-east, a high peak (which we have named Mt. Saskatchewan) lay

between this glacier and the west branch of the North Fork, flat-topped

and covered with snow, on its eastern face a precipitous wall of rock.

Mount Lyell and Mount Forbes could be seen far off in the haze. But it

was towards the west and north-west that the chief interest lay. From

this great snow-field rose solemnly, like ‘lonely sea-stacks in

mid-ocean/ two magnificent peaks, which we imagined to be 13,000 or

14,000 feet high, keeping guard over those unknown western fields of

ice. One of these, which reminded us of the Finsteraarhorn, we have

ventured to name after the Right Hon. James Bryce, the then President of

the Alpine Club. A little to the north of this peak, and directly to the

westward of Peak Athabasca, rose probably the highest summit in this

region of the Rocky Mountains. Chiselshaped at its head, covered with

glaciers and snow, it also stood alone, and I at once recognised the

great peak I was in search of; moreover, a short distance to the

north-east of this mountain, another, almost as high, also flat-topped,

but ringed round with sheer precipices, reared its head into the sky

above all its fellows. At once I concluded that these might be the two

lost mountains, Brown and Hooker.”

The high rock-peak,

which Collie thought might be Mount Brown, was later named Mount

Alberta, while the glacier-clad mountain was christened Columbia. Two

fine peaks, one rocky, the other snow-covered, which from the level of

the icefield hide Alberta, became known as The Twins.

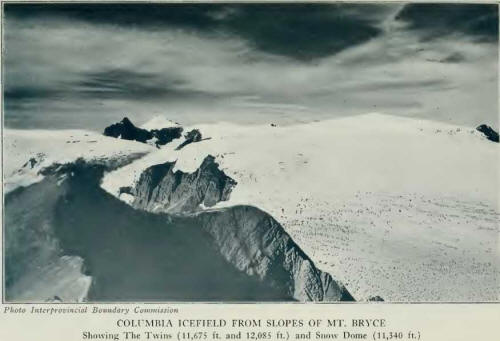

From Thompson Pass, the

Continental Divide swings northward across the eastern shoulder of Bryce

(11,507 feet), and, traversing the centre of the icefield, rises to the

summit of The Snow Dome (11,340 feet), the hydrographic apex of the

Saskatchewan, Athabaska, and Columbia River systems. Almost doubling on

itself, the Divide then turns sharply southward and westward to the

summit of Mount Columbia.

This splendid peak,

attaining the elevation of 12,294 feet, according to measurements of the

Interprovincial Survey, is the second peak of the Canadian Rockies and

is overtopped only by Mount Robson (12,972 feet), the highest of the

entire range. Robson is situated on the Continental Divide, there a

Pacific-Arctic watershed, north of Yellowhead Pass; but it rises from no

icefield comparable to the Columbia.

North Twin, a near

neighbor of Columbia, reaches the height of 12,085 feet, making it the

third elevation of the range and the loftiest summit entirely in

Alberta.

From Mount Columbia,

the Divide crosses Mount King Edward (11,400 feet), and Chaba Peak

(10,540 feet), and peaks along the crest of the Chaba basin, gradually

descending to Fortress Lake Pass (4388 feet).

In the deep valley

north of Mount Bryce, and below Columbia, three crevassed glacier

tongues supply Bryce Creek, which joins with Rice Brook from

Thompson Pass and the

glaciers west of Mount Alexandra to form the North Fork of Bush River

and drain to the Columbia Valley. From Mount Castleguard (10,096 feet),

the Castleguard Glacier tongues form northern sources of Alexandra

River, while to the east of Castleguard Valley minor, separate

snowfields supply Castelets and Terrace Creeks. Above Terrace Valley

rise the shattered, forbidding cliffs of Mount Saskatchewan (10,964

feet), filling in the angle between Alexandra River and the North Fork.

The northern margin of

the Columbia Icefield is bordered by the broad snows of Mount Kitchener

(11,500 feet), and The Twins—South Twin, 11,675 feet; North Twin, 12,085

feet—the latter, as we have seen, the third of triangulated peaks in the

Canadian Rockies. Between The Twins and Mount Columbia a magnificent

precipitous cirque contains the plunging, banded Columbia Glacier and

the tongue from The Twins, draining to the main Athabaska River. The

Twins and Mount Kitchener, grouped with peaks farther north—Stutfield

(11,320 feet), Woolley (11,700 feet), Diadem (11,060 feet), and

Alberta—make up the gigantic massif, as yet but partially mapped,

between the Sunwapta and Athabaska Rivers.

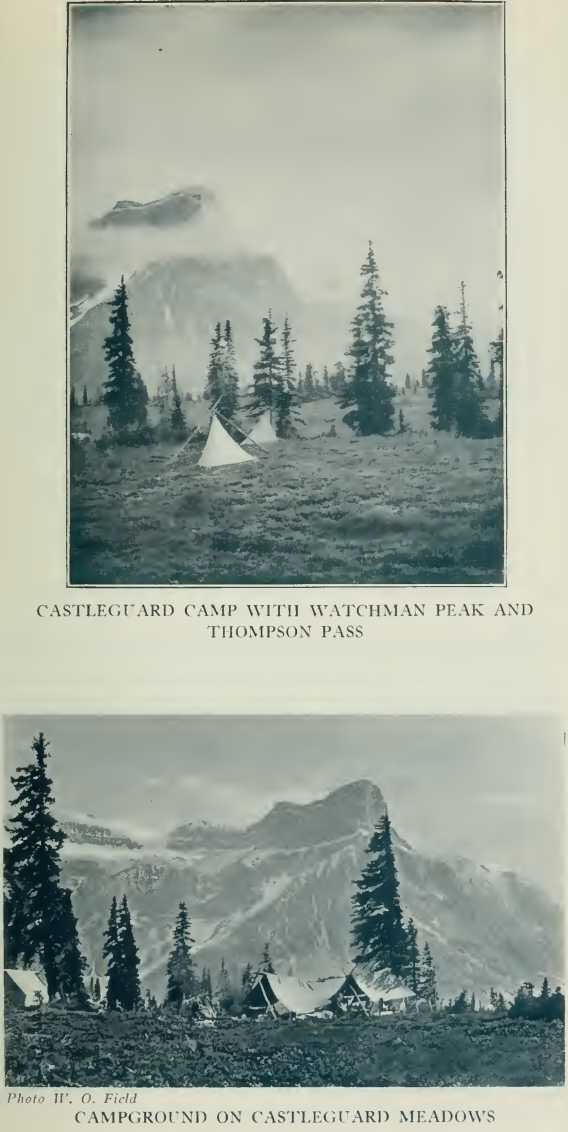

To see these things we

had come up-trail, past Outranks old “Camp Columbia,” with its

surprising waterfall, to campground above 7000 feet in the meadows below

Mount Castleguard and its ice-tongues. Here, indeed, is the spot of

which wranglers dream: plenty of water, wood everywhere, horse-feed for

months; and the horses can’t get away! Castleguard Camp fulfills one’s

idea of Alpine Paradise. A meadow, acres of it,

with a heather carpet

and flowers beyond description; little cascading streams; a tiny canyon,

where leaps an arching waterfall. Can you imagine it at evening? Smoke

from the campfire rising through tall trees beside the tents;

horse-bells tinkling in the distance, as they might on a foreign alpland;

snow summits of Lyell turning heliotrope and violet; shadowed walls of

Castleguard Valley seen to the Bend; Watchman Peak, with Thompson Pass

patched by sunlight, and glimpses of far-away ranges in the west; Mount

Bryce, stupendous, its icy peaks silhouetted and incandescent; the low

southern Castleguard tongue brilliant with light reflected from the

Columbia Icefield; Mount Castleguard itself, and Athabaska, at the

valley head, old-rose and golden. One despairs in the telling of it. It

is a place to which one will return.

From camp, one is but a

short distance from Thompson Pass. Two hours’ walk to the valley head

leads over a low divide to the Saskatchewan tongue, whence Mount

Athabaska could be climbed. East of camp, a range of minor peaks, of

which Terrace (9750 feet) is the chief, separates Castleguard from

Terrace Valley. It is easy to cross a low snow pass below the southern

slopes of Athabaska South station, and reach meadows below Mount

Saskatchewan. Finally, in two hours one may ascend the Castleguard

Glaciers to the eastern ridge of Mount Castleguard, at 9000 feet, whence

a route to the summit is obvious; or, what is of equal interest, one may

circle to the northwest and attain the Columbia neve without having

crossed a single crevasse of any size. As many of the icefield climbs

are of great length, the gaining of altitude and

the avoidance of

icefalls is an immense advantage over Outram’s route to Columbia by the

low southern Castleguard tongue or Collie’s attempted route through the

crevasses of the Athabaska Glacier.

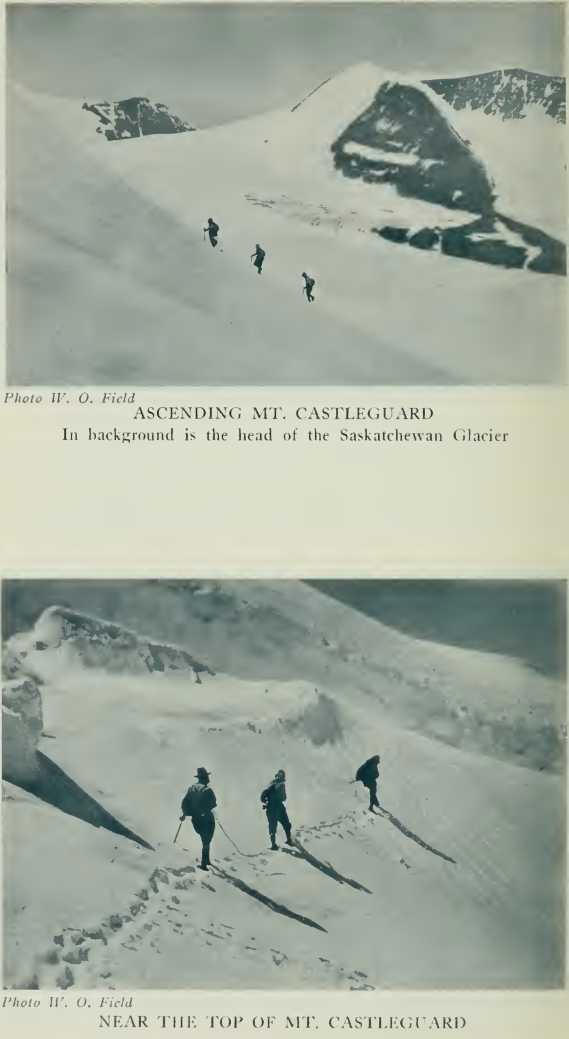

Mount Castleguard, of

which we made the first traverse, on July 6th, affords the finest near

views of the Columbia Icefield. Our entire party went up, including

Simpson, our cook, and our wrangler. Above the eastern ridge, which we

attained by way of the easy central glaciers, are short stretches of

steep snow. A little bergschrund is crossed and the summit reached in

four hours from camp. The mountain dominates Saskatchewan Glacier and

presents a splendid overlook across the icefield, which stretches

endlessly westward toward Mount Columbia and northward to The Twins.

Little misty clouds scud along in the breeze, their shadows wandering

out across the snow and separated by splotches of sunlight. Mount Bryce,

in its sheer grandeur, is nearby, with range after range beyond the

wooded depths of Bush Valley. Mount Forbes lifts a white fang in the

south, while nearer are the flanks of Lyell and Alexandra streaming with

glaciers.

Jim and Conrad are

lying flat on the shale, with a map spread out; there is a great

pointing of fingers toward distant valleys, and the remarks which come

to my ears indicate that fur-bearing animals next trapping season had

best look out for themselves. Ladd and Frog are dividing the last piece

of cheese, and Frog is not getting the best of it. Tommy and I sit with

our backs against the summit cairn; one corner of it is decked with a

mossy fringe of hoar-frost, which

is dripping in the

sunlight and falling into several cups to which we have constructed

elaborate aqueducts of flat stones.

Two hours on the summit

flew rapidly, and we descended the northern Castleguard snow-ridge in

spraying glissades to the icefield. Columbia seemed so near to us; it

was early in the afternoon and we walked some distance toward it before

turning homeward. It was a day of enjoyment for all, although the

momentary disappearance of Tommy through a snow-bridge was startling. We

were fond of our cook, and our morale in those strenuous days depended

much upon his oft-repeated bellow of “Come and get it.” Four meals in a

day never seemed too much!

Next morning a climbing

party of four again ascended to Castleguard shoulder, hoping to reach

Mount Columbia; but cold wind and snow-squalls prevailed, and drove us

ignominiously back to camp where we made short work of a fresh batch of

Tommy’s biscuits. Our labor was not entirely useless, for we packed up

to the ridge a supply of clothing, condensed fuel, and a small tent, to

serve as a high camp in emergency.

July 9th was a day of

threatening weather. Ladd went down-trail toward the Castleguard stream

and tried the fishing, but with indifferent success. Conrad and I made a

little first-ascent of Terrace Mountain (9750 feet), by its southern

glacier and the col at its head. The glacier is small, but offers an

array of wavy, wind-blown ridges of snow, in whose hollows we counted no

less than twelve lakelets, interconnected by ice-tunnels. The mountain,

situated between Castleguard and Terrace Valleys, is without difficulty,

three hours bringing us to the corniced summit, whence one obtains a

map-like view of the Columbia Icefield with its glacier-tongues

extending out, like tentacles of some monster of pre-history. Altogether

it is one of the most satisfactory views in the vicinity, and the

overlook to Mount Saskatchewan served us well a few days later.

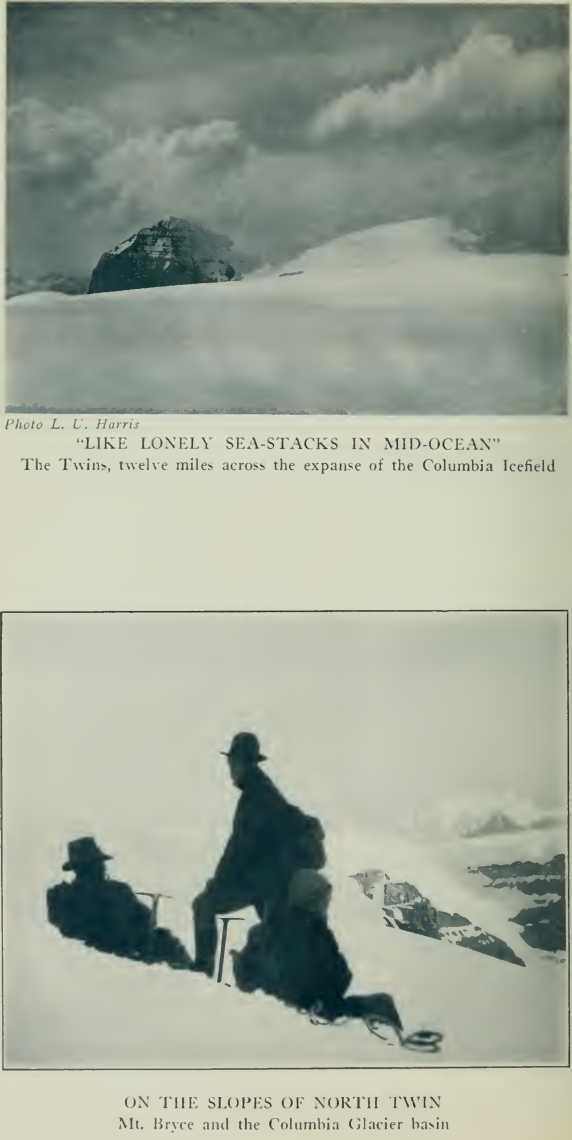

To ascend the unclimbed

North Twin (12,085 feet), had been the great prospective of our journey.

On July 10th we attained this goal. With an early start (3.20 A. M.), in

two hours we were high on the Castleguard ridge and off on the margin of

the icefield. New snow had fallen during the days preceding; bands of

mist raised fingers, swirling skyward, as if to warm them in the glow of

morning. Columbia and The Twins, afar, showed only their upper heights

above the undulating snowy wastes.

We came to know the

Columbia Icefield on that day. It was six o’clock when we left the

ridge. Soft snow and distance: North Twin is twelve miles in air-line

from Castleguard shoulder, but looks less than half of that. One

descends, above the head of Saskatchewan Glacier, into a broad, nearly

level basin, whence the slopes rise gradually along the base of an

unnamed snow-crest adjoining Athabaska on the west. Just this much takes

hours; and, on rounding the head of Athabaska Glacier to the base of The

Snow Dome, one is but half way to North Twin.

The Snow Dome does not

rise conspicuously from the icefield; it is broad-based, situated west

of the Athabaska Glacier, and slopes gradually up to a summit slightly

more than a thousand feet above the main field. It is more attractive

when seen from Wilcox Pass, in which direction it presents gigantic

ice-crowned cliffs and terraces, with a spectacular icefall ending near

the Athabaska tongue. The chief interest of the mountain is in its

position as hydrographic apex of the region. From its slopes, melting

snow flows to the North Saskatchewan; to the Athabaska, through the

Sunwapta River; to the Columbia, by way of Bush River headwaters. These

rivers, flowing to three different oceans, spring from one of the

greatest of Continental watersheds.

As we skirted the

western slopes of The Snow Dome, North Twin loomed apparently close at

hand; but distances are as deceptive as on the ocean, and nearly level

snow hides many deep depressions. We circled widely to avoid crevasses

at the head of Columbia Glacier, which slopes to the Athabaska Valley.

The Twins are an isolated pair, ringed by cliff and icefall, North Twin

alone being connected with the icefield by a snow col—a ribbon of

snow—leading down toward Habel Creek. And after weary hours,2

when one has crossed the last long slopes and plateaus, it is necessary

to lose altitude in crossing this deep saddle to gain the peak.

Here we made the first

stop, for lunch, at two o’clock. Over the head-cirque of Columbia

Glacier rise Mounts Columbia and King Edward, above icy terraces and

benches of cliff. South Twin is close at hand, with grim, pinnacled

walls, towering to a sharp ice-peak, difficult in appearance, and only

to be attacked by the col connecting it with its northern relative.

Framed by North Twin and the snow-humps of Stutfield, the valley of

Habel Creek is a foreground for cliff-ringed and unclimbed Mount

Alberta.3

Our own peak,

immediately above us, its corniced summit ridge intermittently hidden by

snow-flurries and wind-blown mist, rose in a slope of glistening snow,

steep and unbroken. Conrad was leading, I was second, and Ladd last on

the rope. The wall of snow was ever before us as we went up; there was

considerable step-cutting, not in hard ice, but in crusted snow, and our

pace slowed before the top of King Edward came into view above the sharp

arete of South Twin. We reached the summit just thirteen hours after

leaving camp: fleeting glimpses of winding rivers in the west and of

shining summits in the direction of Maligne Lake and Wilcox Pass were

blotted out in the closing mist.

Still, it was warm

enough—just a moderate breeze blowing—and we remained twenty minutes on

the summit; but the view we hoped for never came. The descent to the col

was without incident (4.40-5.40 P. M.) ; we had made the first traverse

of the Columbia Icefield, from Castleguard Valley to the head of Habel

Creek—from the Saskatchewan to the Athabaska slope —and the last

untrodden twelve-thousand-foot peak of the Rocky Mountains of Canada had

fallen to us.

Someone, following in

our track, may one day understand that journey back across the

icefield’s vastness. For an analytical mind, it will at least afford

insight of the psychology of fatigue: the half-hour in a blizzard,

obscuring the trail and exhausting us; the clearing at sunset, with

crimson and orange light banded against masses of lead-blue storm clouds

behind The Twins; mist and snow-banners wreathed about and trailing from

Columbia and catching up the light —we three mortals in the middle of

the field, in all its immensity, struggling on in insufficiently crusted

snow until the light failed.

We had brought some

portable fuel and a small kettle with us and left it on a snowy hummock

far out on the icefield against our return. It was dark when we

approached it, but we soon had some water melted to slake a burning

thirst. While Conrad and Ladd were attempting to make tea, I walked on

alone to the slopes below Castleguard. The unbroken snow was hardening a

little, the air comfortably cool, and only a gentle wind stirring. I sat

down to wait for the others. Beyond Athabaska dark clouds hung and

lightning flashed; in another direction, above Mount

Bryce, stars appeared

in all the glory of high altitudes; in the western horizon there was

still a pale afterglow, and bits of mist floated about on the surface of

the icefield, as if earth and sky were mingled in one.

The rest of the party

came up; I had seen the flickering lantern, and located them by their

shouts. We roped up together and went on through the night, over the

Castleguard shoulder and down the long slopes beyond. It is not easy to

thread crevasses in the dark—lucky that we knew the way, but how we

cursed that lantern! When we pulled into camp, it was three o’clock, and

morning was on the hills as it had been when we departed.

Twenty-three hours we

had been out; we were very tired, and the grass beside the campfire

seemed luxurious in its softness as we sat there breakfasting in the

light of the rising sun.

|