|

“The scenery we were

entering was at once strange and exciting. The common features of Alpine

landscapes were changed; as if by some sudden enchantment we found

ourselves amongst richer forests,

purer streams, more

fantastic crags.”

Douglas Freshfield

For

many years there had existed, among the outfitters, the desire to find a

direct route practicable for horses between the heads of Castleguard and

Sun-wapta Rivers. If this could be done, it would shorten the

transportation time between Thompson and Wilcox Passes. We had had a

good look at the glacier from the summit of Castleguard, and, while the

climbing party was occupied with Mount Saskatchewan, Jim had been

prospecting for a way down.

Two

days after our ascent of Columbia, on July 16th, we broke camp at

Castleguard. It was the loveliest day imaginable, and we hated to go;

the peaks stood out against a turquoise background, so beautifully sharp

and clear, with filmy wisps of multi-coloured, diaphanous mist clinging

to their lower slopes. The tents were down and the last horse packed; we

knew that some day we would come back.

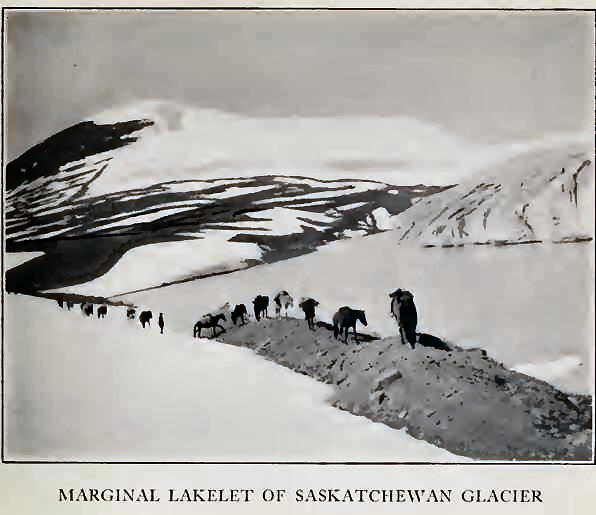

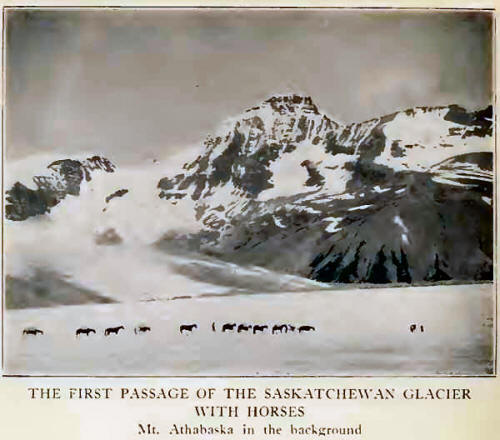

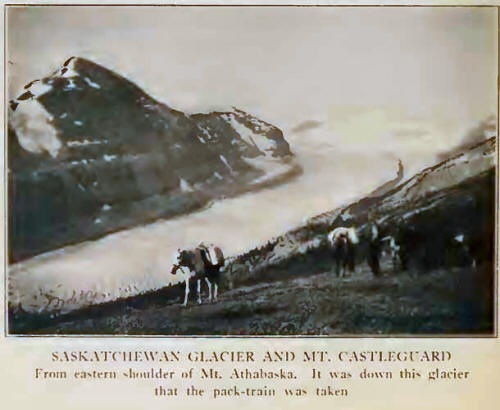

The

ultimate sources of Castleguard River head in a low divide,1

with meadows which we crossed to a tiny marginal lake by the

Saskatchewan Glacier, nearly opposite Mount Athabaska. A shore of flat

moraine permitted the pack-train to progress to level ice. Our horses on

the glacier made an unusual pronto identify

the route, and because of the dominating peak, the name “Castleguard

Pass” is suggested for the pass between the head of Castleguard Valley

and the Saskatchewan Glaciers.

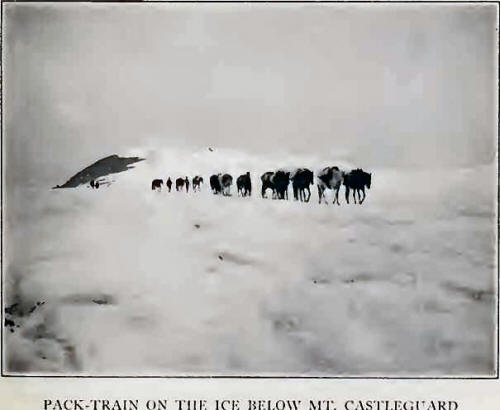

cession; but, at first timid, they soon became accustomed to their

surroundings and, like true mountaineers, hopped over the little cracks

and crevasses. It was necessary, in avoiding a lateral glacier entering

from the south, to take to the central ice for a short distance. The

horses were taken down the glacier for more than four miles, with

devious winding around the large transverse crevasses. The steep

terminal moraine, with treacherously balanced boulders and slippery

glacial mud, was most troublesome, requiring some trail-building and

considerable care to avoid damage to the pack-train. But before evening

the last horse was safely off and camp finally made below the tongue on

the flats toward the south side near a pleasant waterfall. Close by, the

stream enters a narrow canyon, spanned by a natural bridge; apparently

no one else, with horses, had ever stopped at our Glacier Camp.

At

daybreak, without difficulty, we took the horses northward over a

meadowed shoulder east of Mount Athabaska, about 7500 feet in elevation,

whence we looked back and over the tremendous expanse of green ice to

Castleguard. We could scarcely believe that the cayuses had come down

such a place. The descent to Sunwapta Pass was direct, through grassland

and open timber to the river, whence we followed trail across the true

Saskatchewan-Athabaska divide to camp not far from the tongue of

Athabaska Glacier.

It

was a place to remember. The valley-flat, bordered by ancient

timber—from whose dusky shadows rushing brooks emerge—is sparsely

covered by thickets of scrub-evergreen and willow. We spent delightful

minutes in watching the antics of gopher: furry little beasts, and

childishly curious. Franklin grouse, the “fool-hen” of the Northwest,

were abundant; the hens often paraded close to the tents, bringing

several chicks for our inspection and showing not a trace of fear.

Several lakelets on the Athabaska moraine are remarkably deep and blue

for their size; their shores are a salt-lick, crossed and recrossed by

game tracks; four sheep bounded away when we first walked there. Several

days later the cook served up a savory dish which tasted very much like

mutton. None of us could guess where it came from; but, from the grin on

Jim’s face, it is barely possible that he might have solved the riddle.

The

Athabaska Glacier is the chief source of Sun-wapta1

River, the Sunwapta Pass, some four miles southeast of Wilcox Pass,

dividing ultimate sources of North Saskatchewan from Athabaska drainage.

Wilcox Pass is really not a pass at all, but a detour on the Sunwapta,

by which the eastern meadows of Wilcox Mountain are rounded to avoid a

deep canyon below the Athabaska tongue. The glacier itself is

spectacular enough; it descends in three icefalls, from the Columbia

field, through the gap between Mount Athabaska and The Snow Dome. The

tongue flows for more than five miles and spreads in an enormous

uncrevassed fan close to the trail. The headwater of the Sunwapta is

augmented by the fall of Dome Glacier, plunging down between The Snow

Dome and Mount Kitchener. Nowhere else did we observe a greater quantity

of falling ice; scarcely an hour passed without resounding crashes

announcing a streaming avalanche.

By

the north glacier and the northwest arete we made, on July 19th, the

third ascent of Mount Athabaska (11,452 feet). It is such a radiant,

dazzling mountain when the sun shines on its unbroken northern snow; and

it was a pity that we had wretchedly bad weather. The route, above

timber-line, was entirely on snow until the final crest was reached and

an occasional rocky outcrop found. There are several steep slopes where

one must traverse laterally for short distances under a bit of hanging

glacier; some enormous blocks lie frozen high up in the slope, and here

only were we glad that the day was not too bright. Less than six hours

brought us to the summit, a rising snow-wedge, without cornices. It was

snowing hard, and through holes in the fog we had just occasional

glimpses of the Saskatchewan Glacier. There was little to indicate the

presence of the Columbia Icefield, and although it was discovered from

this very point it would have been unseen if the first-ascent had been

made under weather conditions such as we experienced.

The

northwest glacier, by which we descended, is a variant of former routes,

but interesting and repaying because of a tumbling icefall which one may

safely approach. On the moraine we picked up a large trilobite fossil,

quite different from the small shell-fossils which load the strata below

the summit of Nigel Peak across the valley. There is a fine view over

the Athabaska Glacier to the peaks of Diadem and Woolley beyond; but

lowering clouds prevented our seeing very much of it, although the sun

came out again as we reached the lower moraine and walked back to camp.

We

had now completed our northern program as far as weather had permitted.

North Twin, Saskatchewan, Columbia, Athabaska, and lesser peaks had

fallen. The distances covered had been great: we had made two journeys

across the Columbia Icefield— North Twin a round trip of more than

thirty miles; Columbia but slightly less. North Twin, Saskatchewan, and

Columbia had been captured within five days, perhaps constituting, if

there be honour in it, a long-distance and altitude record in Canadian

mountaineering.

Simpson told us an interesting tale, portions of which I was able to

amplify, regarding the fate of Professor Coleman’s folding boat. It

seems that this craft, which had been taken to Athabaska Pass in 1893

for the purpose of navigating the Committee Punch Bowl, was utilized on

the return journey to carry one of the party down the Saskatchewan from

the Kootenay Plains to Edmonton. A canvas boat, presumably the same one,

was again taken by Coleman’s party in 1907, when travelling from Laggan

to Mount Robson. That it never arrived beyond the sources of the

Athabaska is indicated by the statement,3 “As our loads were

heavy and some of the horses had sore backs we cached the folding boat

and fifty pounds of supplies, enough to take us home from this point, in

a thick spruce-tree, fastening everything up tight in bags to keep out

winged or four-footed marauders. We hoped thus to make better time. This

cache we were fated never to see again, and if some later traveller has

not lifted it from the crotch among the branches of the old spruce, it

may be there still in its waterproof wrappings.”

The

cache, near Athabaska Glacier, remained untouched for several years.

Then along came an outfit and camped beside it. An outfitter, waking

suddenly in the night at the scratching of a small animal at the tent

door, and with dreams of a grizzly still confusing him, fired his gun

point-blank. The porcupine seems to have escaped unscathed, but a gaping

hole was blown in the side of the folding boat.

Later in the season Simpson took the boat down to the Saskatchewan

Forks, repaired it and used it for several years at the ford. It was

finally burned up by a couple of Indians who, for reasons unknown, bore

Jim a grudge. Thus ends the strange maritime history of a craft whose

lengthiest voyages were made on the back of a pack-horse through high

mountain regions!

On

July 20th, camp was broken, and in seven hours we had negotiated the

“Big Hill,” past Panther Fall, and the miles to Graveyard Camp. We could

not help walking out on the river-flat that evening for a last look at

Mount Saskatchewan. It is such a magnificent peak, the landmark of the

entire valley, and it seemed no less glorious now that it was ours.

On

the following day we crossed the Saskatchewan ford, camping below Mount

Murchison, and in the afternoon enjoyed a much-needed bath in a warm

shallow lake behind the tents. The old route was followed up the Mistaya

to Wildfowl Lakes and Bow Pass. We had come back from the sources of the

North Saskatchewan—it was journey’s end. |