|

“Even where all men

go, none may have stopped; what all men see, none may have observed

James D. Forbes

The fur-trade was now

at its height and, for more than forty years after David Douglas, groups

of travellers continued to cross the Continental Divide by way of

Athabaska Pass. Few indeed are the individuals who were able or took the

trouble to write down their experiences; yet those who did so form a

strangely interesting company—a priest, a soldier, an artist, a

physician, a surveyor. Remarkable it is that the diverse pursuits of

these men should eventually lead them through a common ground; fortunate

that their dissimilar viewpoints were for a little while united in the

interpretation of the wonders of nature. What matter if the

interpretation was often vague and faulty? The wonder of it is that

every man who left a written record of his journey—though his outlook in

other respects differed completely from that of his fellow-travellers—was

spellbound by the natural marvels confronting him.

In April, 1846, the

Jesuit Father, Pierre Jean De Smet—he who first described the geysers of

the Yellowstone—en route to Oregon Missions, crossed the pass westward.

Spending some time in the Athabaska Valley, and being well received by

its inhabitants, he informs us1 that “Lake Jasper, eight miles in

length, is situated at the base of the first great mountain chain. The

fort of the same name, and the second lake, are twenty miles higher, and

in the heart of the mountains. The rivers Violin and Medicine on the

southern side, and the Assiniboine on the northern, must be crossed to

arrive there, and to reach the height of land at the du Committee s

Punch Bowl, we cross the rivers Maligne, Gens de Colets, Miette and Trou,

which we ascended to its source.”

The missionary gives a

sympathetic description of his leave-taking: “As the time approached at

which time I was to leave my children in Christ, they earnestly begged

leave to honor me, before my departure, with a little ceremony to prove

their attachment, and that their children might always remember him who

had first put them in the way of life. Each one discharged his musket in

the direction of the highest mountain, a large rock jutting out in the

form of a sugar-loaf, and with three loud hurrahs gave it my name. This

mountain is more than 14,000 feet high and is covered with perpetual

snow. On the 25th of April, I bade farewell to my kind friend Mr.

Frazer, and his amiable children, who had treated me with every mark of

attention and kindness.”

Roche de Smet is still

a landmark of Jasper Park, but the visitor of today will not recognize

it from the description of the worthy father!

De Smet further

describes his route, and the objects which interested him: “We resumed

our journey the following day and arrived about nightfall on the banks

of the Athabaska, at the spot called the ‘Great Crossing.’ Here we

deviated from the course of that river, and entered the valley de la

Fourche du Trou. As we approached the highlands the snow became much

deeper. On the 1st of May, we reached the great Bature, which has all

the appearance of a lake just drained of its waters. Here we pitched our

tent to await the arrival of people from Columbia, who always pass by

this route on the way to Canada and York Factory. Not far from the place

of our encampment, we found a new object of surprise and admiration. An

immense mountain of pure ice, 1500 feet high, enclosed between two

enormous rocks. So great is the transparency of this beautiful ice, that

we can easily distinguish objects in it to the depth of more than six

feet. One would say, by its appearance, that in some sudden and

extraordinary swell of the river, immense icebergs had been forced

between these rocks, and had there piled themselves on one another, so

as to form this magnificent glacier. What gives some color of

probability to this conjecture is, that on the other side of the

glacier, there is a large lake of considerable elevation.1

From the base of this gigantic iceberg, the river Trou takes its rise.”

All this information De

Smet has been communicating in letters to his friends at home: “You have

learned that I had arrived at the base of the Great Glacier, the source

of the river du Trou, which is a tributary of the Athabaska, or Elk

River. I will now give your reverence the continuation of my arduous and

difficult journey across the main chain of the Rocky Mountains, and down

the Columbia, on my return to my dear brethren in Oregon.

“Towards the evening of

the 6th of May, we discovered, at the distance of about three miles, the

approach of two men on snow-shoes, who soon joined us. They proved to be

the fore-runners of the English Company, which, in the spring of each

year, go from Fort Vancouver to York Factory, situated at the mouth of

the river Nelson, near the fifty-eighth degree north latitude. In the

morning my little train was early ready; we proceeded, and after a march

of eight miles we fell in with the gentlemen of the Hudson’s Bay

Company. The time of our reunion was short, but interesting and joyful.

The great melting of the snow had already begun, and we were obliged to

be on the alert to cross in due time, the now swelling rapids and

rivers.

“The news between

travellers, who meet in the mountains is quickly conveyed to one

another. The leaders of the company were my old friends, Mr. Ermatinger,

of the Honorable Hudson’s Bay Company, and two distinguished officers of

the English army, Captains Ward [Warre] and Vavasseur [Vavasour], whom I

had the honour of entertaining last year at the Great Kalispel Lake.

Capt. Ward is the gentleman who had the kindness to take charge of my

letters for the States and for Europe.

“Fifteen Indians of the

Kettle-Fall tribe accompanied him. Many of them had scaled the mountains

with one hundred and fifty pounds weight upon their backs.”

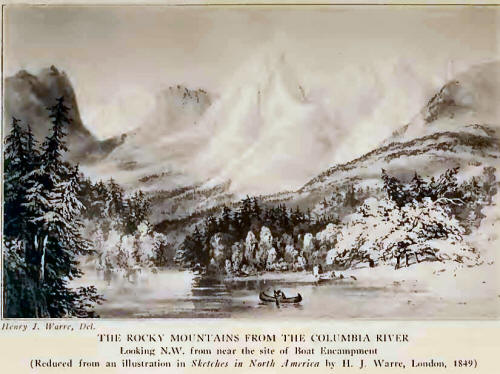

The gentlemen

encountered by De Smet are worthy of some notice. In 1845, when there

was a possibility of trouble between England and the United States

regarding the Oregon boundary, Capt. Henry J Warre,. and Lieut. M.

Vavasour, R.E., were sent by the British Government on a secret mission

to seek out routes for troops through the Rocky Mountains. Returning,

they left Fort Vancouver on March 26, 1846, travelling via Fort Colville

to Boat Encampment at the Columbia Loop.

Captain Warre’s account

of the crossing of Athabaska Pass is brief; but he seems to have been

none the less impressed, for he says,2 “We had

for many days been surrounded by magnificent mountains, and had passed

through such a beautiful country, that the effect of this grand and

solitary scene was partially destroyed by the sublimity of that which

had preceded it. The mountains are about 10,000 feet in height,

unequalled in any part of Switzerland for the ruggedness of their peaks

and beauty of form, capped and dazzling in their white mantle of snow.

“On the fourth day we

ascended the ‘Grande Cote’ to the height of land on which are situated

two small lakes, from whence flow two rivers, the waters of which flow

into different oceans—the Columbia into the Pacific, and the Athabaska

into the Frozen Ocean.

“We had scarcely walked

ten miles, when the joyful sound of human voices assured us of more

immediate relief, and we soon encountered a party of men who had been

sent to meet us with provisions, accompanied by Le Pere de Smet, a

jesuit priest from Belgium, and chief of the Roman Catholic missionaries

in the Columbia district, who was on his return to that part of Oregon.”

Captain Warre was a

trained artist: he published his journal, now one of the rarest items in

the literature of the Northwest. The plates accompanying the few pages

of text are exquisitely done, and present the earliest attempt to

illustrate adequately the scenery of the Columbia Valley.

Following De Smet came

the wandering artist, Paul Kane, to whom Governor George Simpson had

granted permission to cross with the Hudson’s Bay Express. Kane’s

purpose was to make portraits and pictures among the various Indian

tribes—a work which he carried into effect.

Of his westward

crossing, in November, 1846, he writes: “We were now close upon the

mountains, and it is scarcely possible to conceive the intense force

with which the wind howled through the gap formed by the perpendicular

rock called ‘Miette’s Rock,’ 1500 feet high, on the one side, and a

lofty mountain on the other. The former derives its appelation from a

French voyageur, who climbed its summit and sat smoking his pipe, with

his legs hanging over the fearful abyss.

“Today we attained what

is called the Height of Land. there is a small lake at this eminence

called the Committee’s Punchbowl; this forms the headwaters of the

branch of the Columbia River on the west side of the mountains, and of

the Athabasca on the east side. It is about three-quarters of a mile in

circumference, and is remarkable as giving rise to two such mighty

rivers; the waters of the one emptying into the Pacific Ocean, and the

other into the Arctic Sea. We encamped on its margin, with difficulty

protecting ourselves from the intense cold.

“The lake being frozen

over to some depth, we walked across it, and shortly after commenced the

descent of the Grande Cote, having been seven days continually

ascending. The descent was so steep, that it took us only one day to get

down to nearly the same level as that of Jasper’s House. The descent was

a work of great difficulty on snow-shoes, particularly for those

carrying loads; their feet frequently slipped from under them, and the

loads rolled down the hill. Some of the men, indeed, adopted the mode of

rolling such loads as would not be injured down before them. On reaching

the bottom, we found eight men waiting, whom M’Gillverey and the guide

had sent on to assist us to Boat Encampment, and we all encamped

together.”

Kane and his party took

ten days between Jasper House and Boat Encampment—fast time for loaded

men under winter conditions of travel. Just a year later, we find the

artist returning homeward over the pass. He took the hardships of the

road without grumbling and not without a certain good-humour: “We

started one hour before daybreak to ascend the stupendous Grand Cote,

and soon found the snow becoming deeper at every step. One of our horses

fell down a declivity of twenty-five to thirty feet with a heavy load on

his back, and, strange to say, neither deranged his load nor hurt

himself. We soon had him on the track again as well as ever, except that

he certainly looked a little bothered. The snow now reached up to the

horses’ sides as we toiled along, and reached the summit just as the sun

sank below the horizon; but we could not stop here, as there was no food

for the horses. We were therefore obliged to push on past the

Committee’s Punch Bowl, a lake I have before described.

“It was intensely cold,

as might be supposed, in this elevated region. Although the sun shone

during the day with intense brilliancy, my long beard became a solid

mass of ice.”

What a picture it must

have made—that lonely procession, passing the frozen summit lake, in the

twilight; the bothered pack-horse (how well-packed he must have been!)

led by an artist-adventurer, burdened, in that pre-Gillette era, with

his frozen whiskers!

But a more modern day

was dawning. The British Government, interested in locating passes and

routes suitable for railroads, sent out an Expedition, under Captain

John Palliser, which remained in the field during the years 1857-60.

Their physician and chief explorer was Dr. Hector, afterward Sir James

Hector, a man renowned among the Indians for the cures he made among

their people; and well remembered for his long and speedy

winter-journeys with dog-teams.

In February, 1859, Dr.

Hector was at Jasper House contemplating a visit to Athabaska Pass. He

mentions4 that Jasper House “is a small post of

the Hudson’s Bay Company which had been abandoned for some years, but

was this winter again occupied and placed under the charge of Mr.

Moberly, who received us most kindly.

“Jasper House is

beautifully situated on an open plain, about six miles in extent, within

the first range of mountains. As the valley makes a bend above and

below, it appears to be completely encircled by mountains, which rise

from 4000 to 5000 feet, with bold craggy outlines; the little group of

buildings which form the ‘fort’ have been constructed, in keeping with

their picturesque situation, after the Swiss style, with overhanging

roofs and trellised porticos. The dwelling-house and two stores form

three sides of a square, and these, with a little detached hut, form the

whole of this remote establishment. The general direction of the valley

of the Athabasca through the mountains seems to be from south to north,

with a very little easting. Four miles below the fort the Athabasca

receives a large tributary from the W. N. W., which is known either as

the Assiniboine or the Snake Indian River. Opposite to the fort, from

the opposite direction, comes Rocky River, and these two streams, with

the Athabasca, define four great mountain masses. Thus, on the east side

of the river there is the Roche Miette, which although really some miles

distant, seems to overhang the fort. Higher up the valley is Roche

Jacques, and on the west side of the valley, and opposite to these two,

we have the Roche de Smet and Roche Ronde. These names were given long

ago to the mountains, at a time when a great number travelled by this

route across the mountains.”

Dr. Hector always

enjoyed a mountain-scramble, for a few days later he notes, “I started

with Moberly to ascend the Roche Miette, and as we had to follow down

the valley for some miles and cross the river, we took the horses with

us so far. I now saw where we had forded the river the other night in

the dark, and it certainly looked an ugly place, and if we had only seen

where we were going, we might have hesitated to attempt it. Having

ridden about six miles from the fort, we left our horses, and commenced

the ascent of the mountain, carrying with us a small pair of snow-shoes,

with which to cross any bad places we might come to; but as we found the

snow was everywhere hard, with a glassy surface that supported our

weight, we soon left them behind. Indeed it was only at intervals that

we required to cross patches of snow, for we followed a ridge or

‘crate,’ as they call it, from which it had been swept by the violent

wind of the last few days. After a long and steep climb, we reached a

sharp peak far above any vegetation, and which, as measured by the

aneroid, is 3500 feet above the valley. The great cubical block which

forms the top of this mountain, still towered above us for 2000 feet,

and is quite inaccessible from this side, and is said to have been only

once ascended from the south side by a hunter named Miette, after whom

it was named.”

On February 10th Dr.

Hector started up the Athabaska, in company with Moberly, the guide

Tekarra, and a Canadian named Arkand. On the following day they reached

a point opposite to Miette’s House where there was once a trading post,

at the point where the track branches up the Caledonian Valley to Fraser

River, from that which leads to Boat Encampment and the Columbia.

Dr. Hector was now on

the present site of Jasper, describing it as follows: “The valley of the

Athabasca, above Miette’s House, is very wide, and is bounded to the

east by a long mountain composed of the earth shales, with only a few

detached masses of the more massive strata capping them. We now

descended to the south, and passed the Campement du roches, where we

found many signs of former travellers, and among others our friend

Hardisty’s5 name, written on a tree last summer

as he returned from the Boat Encampment, where he had been sent to meet

Mr. Dallas. We then reached the Prairie des Vaches, where we encamped,

intending to take our horses no further, as beyond this point there is

little or no pasture at any season, but especially in winter.”

No further progress was

made, because “Tekarra’s foot is so much inflamed with his hunting

exertions, that he will not be able to guide us up the valley to the

Committee’s Punch Bowl, so I changed my plan and followed up the main

stream of the Athabasca instead. At noon we reached the mouth of

Whirlpool River, which is the stream that descends from the Committee’s

Punch Bowl, and I found the latitude 52° 46' 54". Leaving the rest to

follow up the Athabasca, I ascended a mountain opposite to the valley of

Whirlpool River, and had a fine view up it towards the Boat Encampment.

Having been directed by Tekarra, I easily recognized Mount Brown and

Mount Hooker, which are much like the mountains toward the source of the

North Saskatchewan. They seemed distant thirty miles to the south by

west. At night fall we encamped where high rocky banks begin to hem in

the river.

“After following up the

river for ten miles we found it became quite a mountain torrent, hemmed

in by lofty and rugged mountains, two of which, that were very

prominent, I named after my friends, Mr. Christie7 of Edmonton, and

Moberly.”

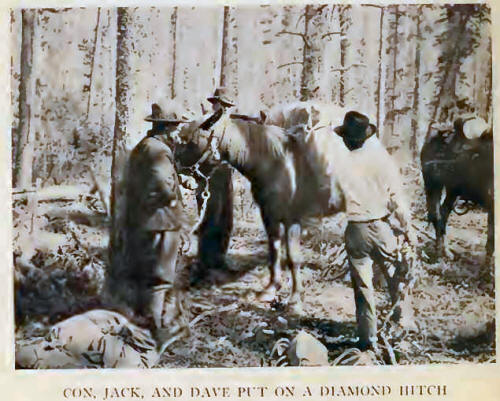

Then came the later,

final exploring for the railroads. During the summer of 1872, Walter

Moberly, having been ordered to discontinue his survey for the Canadian

Pacific Railroad through Howse Pass, came northward across Athabasca

Pass.

On the Columbia River

he writes,8 “We ran many rapids and portaged others, then came to a lake

which I named ‘Kinbaskit,’ much to the old chief’s delight.”

Moberly did not go all

the way to Boat Encampment, but says that on August 27th, “We resumed

our journey and crossed a high ridge, from which the view was

magnificent, part of the Selkirk Mountains, where we could see hundreds

of snow-capped peaks. We waded the [Wood] River many times, and camped

at the foot of Mount Brown, opposite the old camping ground of the H. B.

Company.

“We now began the steep

ascent by the old H. B. Company’s trail to reach the depression between

Mounts Brown and Hooker—the ‘Athabasca Pass’— gaining an elevated

valley, with grassy glades and groves of firs. Where the walking was

fair we made good headway, and camped a short distance north of the

celebrated ‘Committee’s Punch Bowl.’ Following along, and gradually

ascending Mount Brown, we saw a grizzly bear above us, and shot a

ptarmigan, and then coming on a well-beaten cariboo trail, reached the

top of a ridge, with a high conical peak immediately on our right, and a

mass of hard perpetual snow on the north side of the ridge, down which

we went with difficulty, seeing the fresh tracks of four cariboo. There

was a fine view from the top of this ridge, the mountains in the north

forming a magnificent amphitheatre, some five miles in width, and the

innumerable torrents, dashing down the rocks, with white foam like

silver spray, the thick groves of dark fir, the grassy flats and many

small lakes, or ponds, rendering it enchanting.

“From what I saw of it,

my impression is that there is a pass through from the Canoe to the

Whirlpool River, which at some future time may be utilised, but I cannot

be quite certain of the pass, as my examination was very limited, and,

therefore, imperfect. The stream I followed is the true source of the

Fraser, and I had thus been within a comparatively short time at the

sources of the two large rivers of the Pacific Coast, the Columbia and

the Fraser.”

Moberly later returned

to Kinbasket Lake and assisted in getting the remainder of his outfit to

the site of Henry House, where they wintered. His description6

indicates the difficulties under which the early survey parties labored:

“On the evening of the 1st of October the trail was passable though not

finished, as a great deal of corduroying was needed to the foot of Mount

Hooker, a distance of about twenty miles from the Columbia, and nearly

all the animals on the way between the Boat Encampment and the above

point. On the 2nd I started back for Party T, from the foot of the

mountains, taking Messrs. Green and Hall a part of the way up Mount

Hooker to show them where to open the trail and get the supplies to. My

endeavor now was to get the supplies all to the height of land, the

ascent to which in one place is at an angle of about seventy-five

degrees, so that should I not be able to pack them all the way to the

Athabasca depot, before being stopped by the snow, they would be over

the height of land, and there would be a descending grade along the

Whirlpool and Athabasca rivers over which to convey them on dog-sleds.”

Thus we have followed

the stories of the voyageurs over a period of sixty years, forming a

historic tradition excelled in by no other area of the Canadian Alps.

The narratives are many, scarcely two in exact agreement as to detail,

exaggerated as were the tales of the early European alpine wanderers:

yet all possessing a certain fascination in the evident appeal of

natural phenomena to men unaccustomed to mountain travel, but

nevertheless impressed by the strange wonders of a higher level.

Athabaska Pass was one

of the first trans-continental gateways of North America—the first

through which came any large number of white people. Through it passed

pioneers to whom, in a measure, we owe the foundation of civilization on

the North American Continent. Fortunate are we that something of their

story has been preserved. How utterly strange that their difficult

“Height of Land” should become an alpine playground of today! |