|

(The Ascents of Mounts

Kane and Brown)

“Geography is an art

as well as a science. And in parenthesis I may say that I doubt whether

any science is complete which has not art behind it. We shall never be

able fully to know and understand the Earth or to describe what we see

if we use our intellectual and reasoning powers alone. If we are to

attain to a complete knowledge of the Earth, and if we are to describe

what we learn about it in an adequate manner so that others may

participate in our knowledge, then we must use our hearts as well as our

heads. We must be artists as well as meticulous classifiers, cataloguers

and reasoners.

“And, therefore, I

hold that if the function of Geography is to know the Earth and to

describe the Earth, then the objection that the description of its

Natural Beauty is outside the scope of Geography is not a valid

objection. The picture and the poem are as legitimate a part of

Geography as the map.,}

Sir Francis

Younghusband

Twenty years ago, with

an objective group of peaks several hundred miles distant by trail, a

journey to a remote district was not to be lightly undertaken. The early

days of mountaineering in the Canadian Rockies began when there was as

yet no railroad through Yellowstone Pass. Consequently, most

expeditions, at that time—even when bound for the far north—started from

points on the Canadian Pacific Railroad, Banff or Lake Louise.

A. P. Coleman1 and his

companions are responsible for the early enthusiasm, resulting in the

repeated searches for the mysterious high peaks of Athabaska Pass. In

1888, they attempted to enter the region by way of the Columbia Loop,

and actually reached Kin-basket Lake before abandoning the enterprise.

In 1892, a second attempt, by way of North Saskatchewan and Athabaska

headwaters, led them to Fortress Lake —which but for the absence of

Mounts Hooker and Brown, and the discrepancy in the size of the lake,

might have been the Committee Punch Bowl.

In 1893, a third

expedition, led by Coleman, successfully reached the Athabaska Pass. The

highest mountain on the western side of the pass was ascended, and was

considered to be the peak which Douglas climbed.

They also ascended

M’Gillivray’s Rock, the point where Mount Hooker is indicated on the

Palliser map, but noted that “a much higher, finer peak rises a few

miles east of the Punch Bowl, with fields of snow and a large glacier,

and was estimated at about eleven thousand feet.” Because of the small

size of the Committee Punch Bowl, a folding canvas boat, intended for

use on the lake, remained in its pack-cover.

None of the other early

expeditions actually reached Athabaska Pass, although the search for the

high peaks was by no means given up. Wilcox and Barrett in 1896 reached

Fortress Lake. Wilcox triangulated the massive glacier-bearing peak to

the west—the present Mount Serenity—at 10,500 feet.

Habel, the German

explorer, in 1901, spent several days near the lake and mentions

Serenity as “a very prominent snowy mountain, visible nearly from top to

bottom, in shape similar to Mont Blanc.”

Collie, who came out

from England first in 1897, became interested in the Brown-Hooker

problem. In those days, knowledge of the topography was so imperfect

that it was thought that the North Fork of the Saskatchewan had its

source in the neighbourhood of Athabaska Pass. Collie had seen high

peaks in the north, from the slopes of Mount Freshfield, and, in 1898,

visited many of them by way of the North Saskatchewan. The Athabaska

Pass was not reached, but the climbers had their reward in the discovery

of the huge Columbia Icefield.

Following the visit of

Coleman, the next attempt at mountaineering from the pass was made, in

1913, by Messrs. Howard and Mumm,3 of the Alpine Club, accompanied by

the guide Moritz Inderbinen. On the way in from Jasper, minor summits

were attained; but in the immediate vicinity of Athabaska Pass the

weather became so unfavourable that little could be done. Mumm and

Inderbinen ascended Mount Brown and later visited the great glacier—the

present Scott Glacier—at the source of Whirlpool River.

The first ascent of

importance in the Whirlpool Group was that of Mount Serenity, made from

Fortress Lake, in 1920, by Messrs. Carpe, Palmer and Harris. The route

to the summit, by way of the Serenity Glacier and the southern arete,

required ten hours from a camp at the glacier tongue.

In 1920, the

Interprovincial Survey visited the Athabaska Pass and established the

present nomenclature. A large number of stations were occupied,

including Mount Brown, McGillivray Ridge (Mount Brown E.), Alnus and

Divergence Peaks.

The Survey Commission4

published the following conclusions in regard to the Hooker-Brown

problem:

“Mt. Brown. The

mountain ascended by Douglas and named Mt. Brown by him is the one

rising directly on the west side of the pass summit, the altitude being

9156 feet, 3405 feet above the pass.

“Mt. Hooker. The

location is not so clear. Douglas writes in his journal, (1) ‘A little

more to the south is one nearly the same height, rising more into a

sharp point which I named Mt. Hooker.’ (2) ‘I set out with a view of

ascending what appeared to be the highest peak on the north or left-hand

side.’ Against these statements is the fact that the direction of the

valley at the summit of the pass is practically north and south and

consequently Douglas’ ‘north or left-hand side’ would truly be ‘west or

left-hand side;’ so also with reference to Mt. Hooker, ‘a little to the

south is one nearly the same height’ would truly be ‘a little to the

east is one nearly the same height.’ Douglas’ idea of his direction

seems to have been as inaccurate as his idea of altitude. On a bearing

18° north of east lies a peak, rising into a sharp point,

Mr. Cautley describes,

among other things, the discovery, just north of the pass summit, of the

musket-balls lost by David Thompson a hundred and ten years before. (See

Chapter VIII, p. 111.) which is distant approximately six miles from the

summit of Mt. Brown and which has an altitude of 10,782 feet, or 1626

feet more than that of Mt. Brown. It seems more likely that this is the

mountain Douglas refers to as Hooker. (This is the mountain seen by

Coleman and Stewart, and estimated at 11,000 feet.)

“From the vicinity of

Fortress Lake this mountain peak stands up in a sharp white cone. It is

not conceivable that the long, evenly crested ridge (i. e., Mc-Gillivray’s

Rock) rising directly above the Punch Bowl from Athabaska Pass summit

has anything to do with the question. It was, therefore, recommended to

the Geographic Board that the 10,782 foot peak about six miles easterly

from Mt. Brown be confirmed as Mt. Hooker, which has been done.” Thus

rests the question officially.

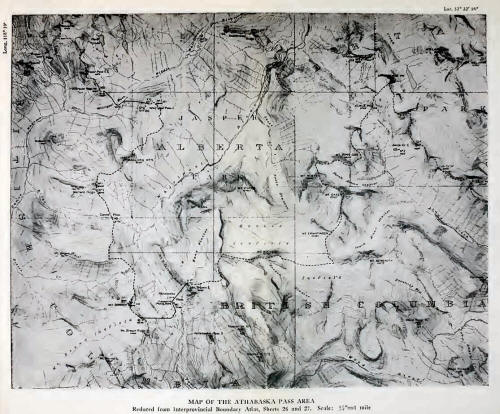

For a moment let us

consider the modern topography of the mountains south of Jasper. The

Whirlpool Group occupies the rough triangle enclosed between the

Whirlpool and Athabaska Rivers on west and east, and by Fortress Lake

and Wood River on the south. It includes the portion of the Continental

Divide between Fortress and Athabaska Passes, an airline distance of

twenty miles, and its continuation to Whirlpool Pass. The air-line

distance between Athabaska and Whirlpool Passes is eight miles.

The northern tip of the

group, in the angle of the Whirlpool-Athabaska junction, although

visible and but a day’s trail-riding from Jasper, has yet to be mapped.

In this angle is a striking peak, known by local name as “Whirlpool

Mountain,” south of which, with its upper crags visible from Jasper

above the eastern shoulder of Mount Edith Cavell, is Mount Fryatt

(11,026 feet), one of the outstanding mountains of the Park. Other peaks

east of the Divide, included in the mapped area, are Lapensee (10,190

feet), and Belanger (10,200 feet), just south of Fryatt; while farther

east, Mount Christie (10,160 feet), and Brussels Peak (10,370 feet),

culminate a sub-group toward the Athabaska. Only a few miles north of

Fortress Mountain, Mount Catacombs, attaining 10,800 feet, is the chief

peak in the southeastern section.

From Fortress Pass

(4388 feet), and Fortress Mountain (9908 feet), the Divide westward

includes no peaks of importance as far as the head of Alnus Creek. At

the western end of Fortress Lake, Alnus Valley enters Wood River at an

acute angle from the northwest. At the head of Alnus Creek, low passes

lead over to Divergence Creek, a Whirlpool tributary, and form a major

trench extending through the Whirlpool Group.

It is chiefly with the

area west of Alnus and Divergence Valleys that mountaineering interests

have been concerned, as this portion of the group contains important

peaks and many of the finest scenic features.

At the head of Alnus

Creek, on the Divide, is Divergence Peak (9275 feet), whence the

watershed swings sharply southward, crossing the summits of Alnus (9673

feet), Ross Cox (9840 feet), Scott (10,826 feet), Oates (10,220 feet),

and Ermatinger (10,080 feet) The watershed now swings abruptly westward,

crossing Mount Hooker (10,782 feet), and, route from the Whirlpool to

Wood River, and we noticed tracks, high on the snow, on several

occasions.

The air-line distance

between Divergence Peak at the head of Alnus Creek, and the Committee

Punch Bowl on Athabaska Pass, is twelve miles. On the Pass summit (5736

feet), are the Punch Bowl and two other adjacent lakelets, giving rise

to terminal sources of the Whirlpool River, on the east, and Wood River,

through Pacific Creek, on the west.

The Continental Divide

continues from the Pass, rising westward to the summit of Mount Brown

(9156 feet), thence turning northward and dropping to the icy lakes at

the head of Robert Creek, and to Canoe Pass (6772 feet), connecting

Whirlpool River with a branch of Canoe River. Crossing Mallard Mountain

(9330 feet), the Divide reaches Whirlpool Pass (5936 feet), linking the

Middle Whirlpool with the Mazama Creek branch of Canoe River. It will

thus be seen that there are no peaks of importance immediately west of

Athabaska Pass and the Whirlpool; the Divide is relatively low and can

be crossed at several points. The feature of interest is the large area

of glacier and snowfield on the southwest side of Mount Brown, extending

into the angle between Wood and Canoe Rivers. The Continental Divide

bends considerably in rounding the head of Whirlpool River, consequently

the air-line distance between Divergence Peak and Whirlpool Pass is only

about eight miles, practically equal to the distance between Athabaska

and Whirlpool Passes.

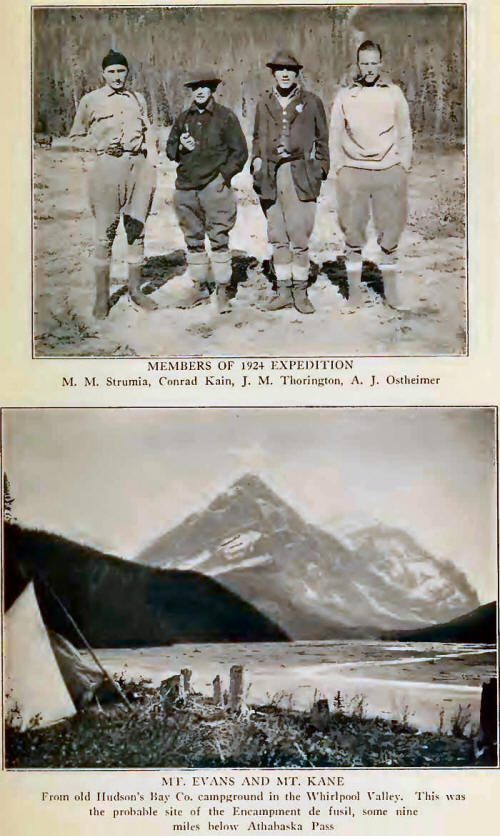

The author’s

expedition, in 1924, was the third to reach the Athabaska Pass for

purely mountaineering purposes. Fortunate were we in coming to a place

so little known—new peaks were everywhere at hand. Within a short space

of time we were able to make the first-ascent of Mount Hooker and other

peaks of the vicinity, and to explore the intricacies of the Kane and

Hooker Icefields, as well as a portion of the vast topography of the

Mountains of the Whirlpool.

From the Canadian

National Railroad, with fourteen horses furnished by the well-known

outfitter Donald Phillips, our party, including Mr. Alfred J. Ostheimer

and Dr. Max Strumia of Philadelphia, myself, and the guide Conrad Kain,

left Jasper on June 26th, bound for Athabaska Pass. In charge of the

horses came David Washington Moberly, a Cree breed, grand-nephew of

Walter Moberly who years before served as locating engineer for the

Canadian Pacific. Our cook, Jack MacMillan, had assisted his father in

building the first trails to Emerald Lake, and had worked for the

pioneer Tom Wilson in the old days.

By road leading from

The Lodge, across the Miette bridge, toward the snows of Mount Edith

Cavell, we started up the Athabaska Valley, a broad trail bringing us to

the mouth of Whirlpool River, the stream which we were to follow to its

southern sources. Here was the location of the old ford—la Grand

traverse— by which the voyageurs crossed to the Prairie de la Vache, or

Buffalo Prairie, on their way to Jasper House.

Past the snow-powdered

crags of Kerkeslin, through a broad valley, there are glimpses of

distant peaks on the Sunwapta and Chaba; while looming in the Athabaska-Whirlpool

angle, companion to many another dark tower, the precipices and

pinnacles of the Whirlpool Mountain, grim and repellent, hide the

towering mass of Fryatt, loftiest of the Whirlpool Group.

Through a small

lumber-camp, where railroad-ties are cut and floated down to Jasper, we

passed and camped by the Whirlpool, quiet pools nearby reflecting Needle

Peak, guardian of the entrance to Simon Creek—the old “North Whirlpool.”

Across the river, sunset colouring of the range blends with the dull,

glowing embers of our campfire: soft wind-music in the jack-pine tops;

rush of the river; distant bells tinkling—first days on the trail are

well-remembered.

The second elevation in

the central area of Jasper Park,5 Mount Fryatt, has long been recognized

by climbers as a mountain difficult to approach. Situated back from the

river, with heavily-wooded slopes, a formidable looking peak it is;

rising so much above its neighboring valleys that mountaineers have left

it severely alone. The Interprovincial Survey had photographed it from

the southwest, from the head of Alnus Creek, revealing the presence of

three attractive lakes and high meadows at the sources of Divergence

Creek, the Whirlpool tributary immediately west of Mount Fryatt.

On June 27th we crossed

the Whirlpool by a lumber-camp bridge, and attempted to take our horses

up the creek west of Whirlpool Mountain to a low pass leading over to

the head of Divergence Creek, where it seemed possible that we might

establish a high camp. We were unsuccessful in our effort. After several

hours in the dense timber, we gained an elevation of less than 6000

feet, where canyons and cut-banks make the creek bed almost impossible

for horses. It would have been necessary to spend one or two days

cutting trail through the high timbered shoulder on the west bank of the

stream in order to reach the desired upper levels.

While we were

investigating the route, several restless pack-horses succeeded in

dislodging one of their fellows over a low rock ledge, the horse turning

a complete somersault and landing head downward in the water. It

required quick and skillful work on the part of the guides to cut the

pack ropes and prevent the struggling animal from drowning. As usual,

more damage was done to the packs than to the horse; but the delay

assisted our decision not to proceed farther. So we recrossed the

Whirlpool and camped on a terrace, by an old cabin not far from the

mouth of Simon Creek.

Passing by the

cook-house of the lumbermen, we were just too late to witness a lively

incident. The cook, preparing lunch, had heard some scratching noises on

the roof of the house. Thinking it was a squirrel, he did not pay much

attention to it, but, happening to look up suddenly through the little

skylight above, found himself looking squarely into the face of a large

black bear. Both were immensely startled, the bear being much the more

frightened of the two. The cook threw a frying-pan full of hot grease

straight up in the air; bruin made an unceremonious dive over the eaves

and galloped off amid a shower of kettles and dishes. We arrived in time

to help the cook gather up his scattered utensils, and to confirm his

story by examining the muddy paw-marks on the cabin roof.

When we returned along

this trail, more than a week later, we found that a sudden rise of water

had carried away the bridge over the river. So future visitors,

approaching Mount Fryatt from this direction, will cross a difficult

ford. From our camping place, evidently a very old one, we could see far

sunlit peaks —Scott, Hooker, Evans, Kane—toward the head of Whirlpool

River. How thrilling is the anticipation aroused by the first distant

view of an unexplored group!

Morning came, brilliant

after a night of heavy showers. In two hours we had forded Simon Creek,

happily without wetting any packs. Then over parallel timbered ridges,

with intervening muskeg and shallow reedy ponds, emerging on river-flats

opposite the ribbed cliffs of Mount Scott, with new snow melting and

sparkling. Then into the timber again, arcaded groves of cottonwood,

with the Middle Whirlpool coming down in no apparent bed of its own, but

spreading about the gnarled tree-roots, and the pack-train splashing

through. It was as if one wandered in a splendid irrigated garden; a

garden of primeval trees, grey-green in their veils of hanging moss,

with tops so interlaced that only here and there might shafting sunlight

penetrate the forest shadows.

As we neared the

timbered point which is the campground, the magnificent ridges of Mount

Hooker, with walls of twisted strata above the Scott icefall, slowly

revealed their grandeur. Near our tents was an old roofless log-cabin,

of spacious dimensions, with hand-forged nails in its crumbling walls.

There are huge stumps in the clearing, so rotted that a touch will

topple them over. We picked up bits of hand-made boxes with marks of the

Hudson’s Bay Company still legible. Not far away, on a bit of cliff,

four goats looked down in silent astonishment at our caravan’s arrival.

In the evening, white-tailed deer passed close to the campfire on their

way to the river: graceful and unafraid they moved along the

gravel-bars, from one silvery pool to another, and disappeared at last

in the sun-glint along the edge of the bush.

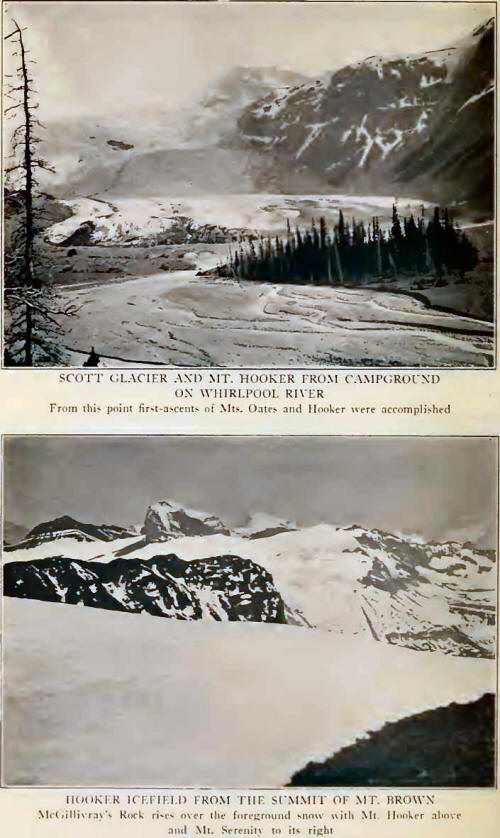

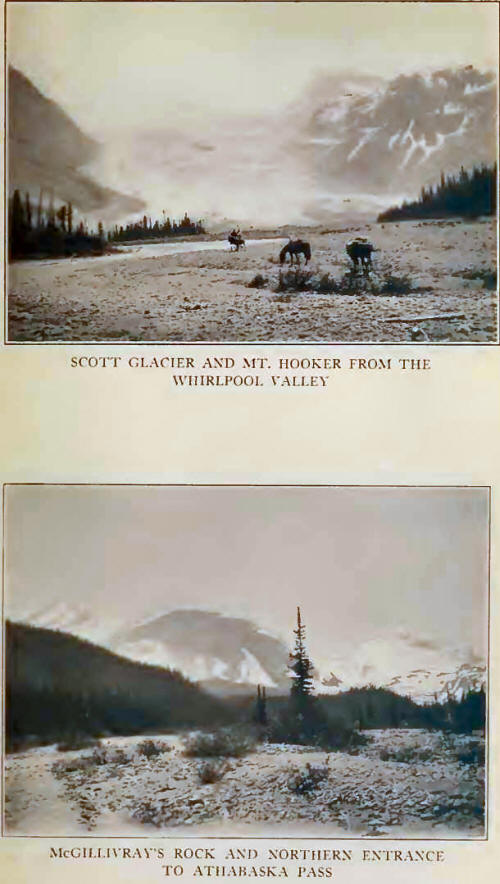

The Scott Glacier will

be much visited in days to come because of the tremendous spectacular

icefalls in which it plunges down to the valley level, to spread in a

broad flat tongue toward the wooded morainal fans far below timber-line.

We passed close below it on our next day’s travel and were to know it

better within a short time. The upper neve spreads below the northern

wall of Mount Hooker, and one must journey far in the Canadian Rockies

to find ice-scenery which can compare with the wild splendour of this

view. The western margin of the glacier is flanked by the symmetrical

rock peak of Mount Evans, contrasting with the sheer snowy wall of Mount

Kane just beyond, resembling the southern portion of the Victoria ridge

above Lake Louise. From the col between Evans and Kane a slender

precipitous icefall hangs in apparent defiance of the laws of gravity,

pale-blue with a tinge of green, and its tiny stream ending in an airy

waterfall that sprays to a rock-bowl close to the trail.

Rounding the shoulder

of Mount Kane, trail leads through evergreen timber and thickets of

pussy-willow, and patches of spring snow. Crowded clusters of anemones

and avalanche-lilies press up through the melting margins. In the shadow

of McGillivray’s Rock, with the snows of Mount Brown ahead, we enter on

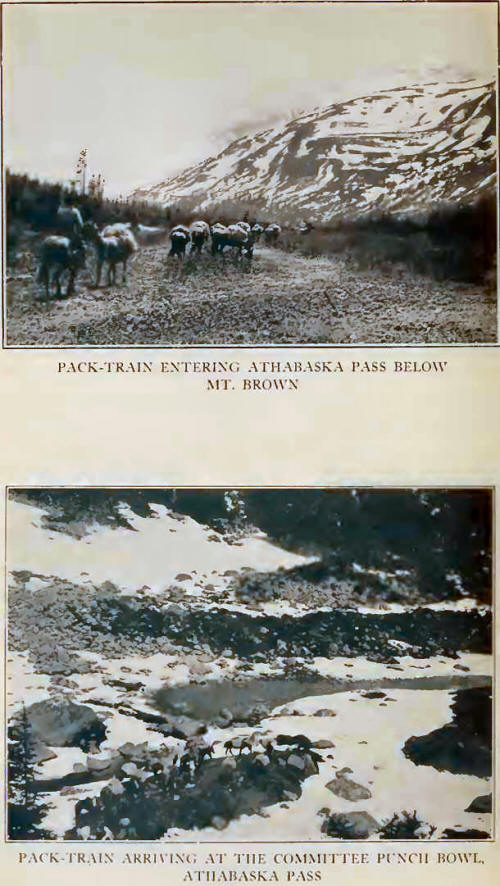

the Athabaska Pass.

The valley broadens

above the gorge at the foot of Kane, snow becomes deeper, entirely

covering the trail; pack-horses, floundering at first, gradually gain

confidence in their footing. A gaunt cariboo stalks up and over a nearby

ridge, moving so slowly. How surprising, to reach the summit lakes on

the pass and stop by the central one—the Committee Punch Bowl! A skim of

ice lay on the water, too cold for bathing; and, unlike Coleman, we had

not brought a canvas boat. But one of us can at least be credited with

having swum a horse across the Great Divide! Here Thompson and Douglas

had come; here Ross and Simpson had drunk their wine; here had passed De

Smet and Kane, and all the rest. . . .

The lakes are desolate,

lonely tarns, and in winter may be entirely covered. Of course there are

no lofty mountains on either side, and one is almost at a loss to pick

out Mount Brown, for on the western side of the pass are several summits

all about equal in height and resembling each other in outline. It is

all so plain in Douglas’ journal; a visit to the pass is the really

confusing thing. A traveller of today, writing on the spot, could never

describe the pass and its peaks in Douglas’ words—the journal and the

lay of the land simply do not agree.

On account of the snow,

we placed camp among the trees on Pacific Creek about a mile below the

pass summit, with a group of serrated splintered peaks in view down the

valley of Wood River.

Hoping to reach Mount

Hooker, on June 30th we left camp at 5.20 A. M. Following the north

margin of the glacier-tongue coming from the shoulder of McGillivray’s

Rock and the Kane Icefield, in two hours we had reached the upper snows.

But on crossing to a higher ridge of the Divide, at 9300 feet, we found

ourselves cut off from Mount Hooker’s southern wall by an impassable

snow precipice, overhung with cornices and dropping to the broken Wood

River glaciers of the Hooker Icefield. The arete connecting with Hooker

rises into an intervening peak which would have to be traversed and

forms a route impossibly long for a single day. So realizing that we

were defeated, we followed our ridge northward and tramped the long

stretches of snow to the Kane-Evans col, which we reached over a small

schrund and up some slabby chimneys. We were now at the head of the

hanging glacier which is so striking in appearance when seen from the

Whirlpool, and upward over snow and ledge made our way to the top of

Mount Kane. It was a few minutes after two o’clock when we arrived.

A little to the

southeast there is a break in the curiously banded rock-wall separating

the Kane Glacier and Hooker Icefield, affording a possible approach to

Mount Hooker; but from Athabaska Pass it will be a very long journey.

Beyond the north face of Hooker the view extends to far-away Athabaska

sources, with Mount Alberta, The Twins, and Mount Columbia, stupendous

even through the distances.

The Wood River Group is

seen from an unusual angle and presents a fine array of glacial cirques

on the northwest, by which the flat upper snows of Bras Croche might be

reached and other peaks explored. Yet one hesitates to recommend a visit

by way of Athabaska Pass and the low, timbered reaches of Wood River.

The northern snows of

Mount Kane, so steep they are, seem to overhang the Whirlpool. It was

the first summit from which all four of the 12,000 foot peaks of the

Rockies are visible that any of us had attained. Far beyond the Rampart

Group and southern Fraser sources, our gaze was held by Mount Robson.

Towering nearly two thousand feet above its highest neighbours, its

elevation emphasized by low surrounding valleys, one is yet attracted

more by the mountain’s isolation than by its appearance of height. No

great group masks its precipices. From our viewpoint the peak is a

steep-angled pyramid, slightly blunted in the summit ice-cap, a

streaming glacier continuous with the neve in a vertical rise of nearly

4000 feet, and the southeastern shoulder, conspicuous from the Grand

Forks Valley, so fore-shortened as to be almost unrecognizable.

The west is a chaos of

unravelled topography: the northern peaks of the Columbia Loop, the

Fraser-Canoe divide, the Gold Range, the Cariboos and far peaks of the

Fraser Valley. Long familiarity with the main chain of the Canadian

Rockies cannot dull the overwhelming sense of hopeless awe aroused by

the extent of those unnamed western peaks.

It is not easy or

profitable to describe precisely the Kane traverse. Suffice it to say

that the arete west of the summit affords a delightful climb of several

hours, with work which does not lack in excitement. The snow-ridges

encountered are quite narrow, with airy drops to the Whirlpool Valley;

the arete possesses a blunt central tower, with opportunities for

interesting hand-and-friction traverses on the southern slabs. A last

curling ladder of snow leads to scree slopes, and broken rock descending

to the glacier. We walked home across the Kane field, in the lengthening

shadow of McGillivray’s Rock, and the evening glow on the ranges beyond

Wood River. At precisely 8.20 P. M., Jack was requested to cook an

enormous supper for four!

On the following day we

wandered up Mount Brown, past ice-glazed lakelets on benches of snow,

like gigantic steps, above the Committee Punch Bowl. Then following the

eastern margin of the Brown Icefield, we took what climbing we could

find—the rope was unnecessary—and were soon walking up the long shale

ridge to the top. The ascent took five hours, and we arrived at a

quarter before three; the time was slow, but it was a blistering day and

we were a lazy lot. Still it makes one doubtful whether David Douglas,

under winter conditions and with limited time due to a late start, could

have reached this particular summit.

The Brown Icefield

drains to Canoe River and to Wood River; the peaks on its western

margin, all unnamed, are attractive and should preferably be reached

from a camp at the head of Jeffrey Creek. The unnamed pass through the

Divide, immediately north of Mount Brown, deserves a visit. Three lakes,

icy and varying in hue, form the sources of Robert Creek and drain to

Canoe River. The Wood River and Columbia Groups are practically in line,

Alberta and The Twins visible, but Columbia hidden by square-topped Bras

Croche. Two hours passed; cameras clicked busily, pipes were smoked; we

snoozed in the sunlight. The view delighted us—we could not think of it

as being “too awful to afford pleasure.” In another two hours we had

glissaded merrily back to the campfire, tracking in over the lower

snow-patches just before seven o’clock. |