|

“Starving men are

early risers.”

Gabriel Franchere

“They were awakened

by the severity of the cold, and there was no walking to procure

themselves warmth: the day was never so long in coming, and the night

seemed never to have an end. They set out again at day-break, as

benumbed as Marmotts, and it was some time before they could recover the

use of their limbs.”

Bourrit

Feeling that we had

made a satisfactory reconnaissance of the Athabaska Pass and its

surroundings, we returned down the Whirlpool, on July 2d, and camped

near the Scott Glacier, beside a shallow lake in the wooded moraine. It

was a day of travel when Nature seemed pleased to show us her valley

inhabitants—the soaring eagle that guards the rock of McGillivray; a

lonely startled duck skittering across the Punch Bowl; marmots playing

and boxing in sunny snow-patches beside the balsam trees. Flowers

everywhere: columbine and heather; Dave, our Indian, riding ahead with a

bright bouquet nodding from his hat.

A night of

thunder-storms; the morning of July 3d clearing slowly after a

threatening dawn. Such an electrical display and a pounding of thunder

there had been—crashing and reverberating. During the flashes, white

ghostly figures could be seen scurrying about, making the canvas secure.

Now and then one would hear a muffled clanking on the gravel, indicating

that the interior of a tent had been vacated by axes which might serve

as impromptu lightning-rods. We believe this to be not entirely

superstition; on the ridge of Mount Brown many pitted slabs of shale

were found, with square-cut holes where metallic crystals had been

cleanly destroyed by electrical agencies.

We made a late start,

at half-past nine, expecting only to prospect the Scott icefall for a

route to the upper basin. Our camp in the Whirlpool Valley was quite low

(4500 feet), and it was on this account that we had first investigated

the higher level of Athabaska Pass. We now had our tents within a

quarter-mile of the ice, and soon passed the huge isolated boulders of

the terminal debris and were on the flat tongue. The nearly level ice

can be traversed for about a mile, and the eastern moraine, below Mount

Scott, brings one almost to 7000 feet before it becomes necessary to

rope and take to the ice again.

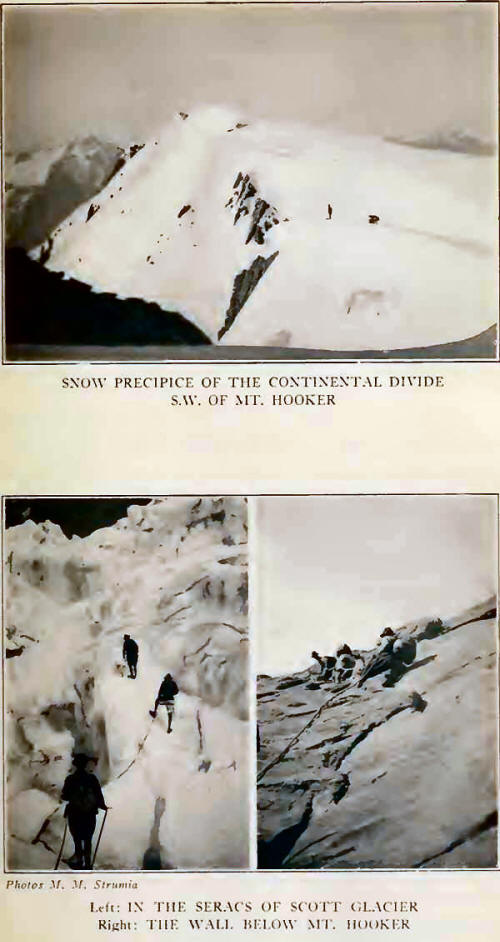

The glacier plunges

down from the Hooker neve, at an elevation of 8000 feet, through the

portal between Mounts Scott and Evans, with a width of nearly a mile.

The fall is extremely broken, with gigantic seracs on the verge of

tumbling. A fragmentary medial moraine is formed through the erosion of

a buttress, partially exposed in the middle of the icefall, at which

level there is a lessening of the ice slope before the final drop to the

bulbous tongue.

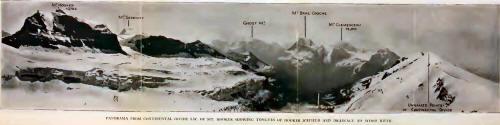

From our roping place,

one ascends another thousand feet before reaching the Hooker Icefield in

the extensive basin between Evans, Hooker, Ermatinger, Oates, and Scott.

This entails a good deal of step-cutting and some careful icemanship; it

was half-past one before we were through. The basin is more than three

miles across, and from cols in its bounding ridges—the eastern and

southern are on the Continental Divide—other icefalls, all badly

shattered, pour in until the field presents a wild scene of unsupported

pinnacles and broken seracs over an extended area. A. L. Mumm who, with

the guide Inderbinen, visited the lower reaches of the glacier in 1913,

wrote of it, “We were in the centre of an immense battlemented cirque,

and straight ahead of us, in particular, stood out against the sky the

most menacing array of towers and pinnacles I have ever seen.” There is

very little in other Canadian icefields with which to compare it: one

thinks rather of the northern glaciers of Mont Blanc as they come down

from the Grand Plateau, but the Hooker Icefield gives an impression of

greater breadth and breakage.

Turning eastward and

rounding the cliffs of Mount Scott, our way lay across a flat of snow,

toward a tumultuous waterfall, a broad gully of shale bringing us

quickly to an upper snow plateau between Mounts Scott, Oates, and

Ermatinger. It was a quarter past two.

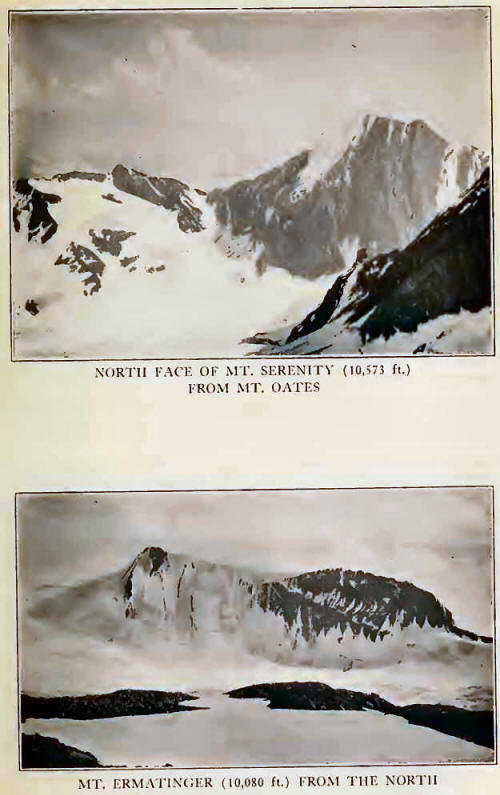

Mount Ermatinger is a

mountain of inspiring beauty: a long, knife-edged arete, rising from the

Hooker Icefield in a jagged crest of uptilted rock strata, continuing

into the north face and merging with a sheer, fluted wall of shining,

green ice. The ice-wall is nearly a thousand feet high, broad and

unbroken; in our combined experience we could think of but few so

glorious. More than anything else it suggested the oncoming mass of a

curling sea-wave, about to break and with the sunlight in its crest. Had

time and weather permitted it would have been ours within a few days,

the difficulties being easily avoidable. We passed it by with regret,

envying those who will first stand on its lovely heights.

We had still the

opportunity of making a climb and it was necessary to decide upon the

most accessible peak. We had been heading for what seemed to be the

highest of the group, believing it to be Mount

Scott. The peak

adjoining Ermatinger on the north we took to be Mount Oates; but on

closer examination of the ground we saw that this is a lower, unnamed

summit—which will give someone an enjoyably strenuous climb—and that the

peak we were approaching was really Mount Oates itself. We climbed to a

little col overlooking the South Alnus Glacier and followed up the ever

steepening shale and rock to the summit (10,220 feet). On the last

thousand feet the rope was discarded.

Not far away, and only

six hundred feet above us, were the shale-tops of Mount Scott, with a

lengthy talus slope of moderate angle running down to the snow plateau.

We had been told that the mountain would afford good rock-work, but from

this side it looks monotonously easy. Our own peak was immensely

preferable. The only way to climb Scott, with pleasure, will be by its

western wall.

Although it was 5.45 P.

M., we settled down to enjoy our surroundings. Below us, on the north,

there was a profound drop to the North Alnus Glacier, while down Alnus

Creek the waters of Fortress Lake were completely in view. Alberta, The

Twins, and Columbia limit the southeastern horizon, and one might trace

the Divide around the head of the Chaba icefields, across Fortress Pass,

up to the acute angle at Divergence Peak; and back again to the

conquered peak where some of us—not all—were hard at work

cairn-building. Thence southward goes the watershed, around the Hooker

basin and the subsiding ridges, shimmering in the saffron light of

evening, that carry it to Athabaska Pass. And beyond Mount

Ermatinger—we were

always looking back—the majestic northern walls of Serenity, its lower

slopes in the long shadows that fill the valley of Fortress Lake and the

head of Wood River.

The return was a race

with daylight. It took us only an hour to return to the top of the

seracs (7.15 P. M.), and two hours more to go down through the intricate

labyrinth. We were soon off the upper ice, and, thanking all natural

forces for the long twilight of northland July, made camp at half-past

ten, just as darkness became annoying. We are convinced that, in most

instances, approaching darkness is tantalizing in inverse ratio to the

distance from the frying-pan! On the upper snows it doesn’t matter so

much; in the last uncertain scrambling in the moraine and glacial brook

it brings out profanity.

July 4th was a day of

rest in camp. The National Holiday was celebrated with spasmodic efforts

at bathing and laundry, and in the futile attempts to construct

steam-bombs out of jam tins. Conrad was the object of much photographic

activity; all the horses of the pack-train followed him into the pond—we

had been out from Jasper for more than a week and there was a lot of

salt on his hide!

Next day, July 5th, an

ascent was begun which eventually took more time than we had expected.

In fact it turned out to be something of an endurance record for a

Canadian climb—a record that we have since been told we are quite

welcome to. We started for Mount Hooker at a quarter before five, taking

forty-five minutes to the ice and an equal time to the rocks at the foot

of the west wall of the glacier. In selecting the wall, below Mount

Evans, it had been hoped to establish a quicker approach to the upper

snows than had been found in the ice route to Oates. Further, the rocks

offered a more direct route to the mountain. It proved not to be so

short.

Two twenty-foot

chimneys were followed by ascending ledges and slabs, and consumed an

hour. We traversed southward and upward across a slanting watercourse

and crossed below a large waterfall in the center of the wall. By

re-entering this gully it seemed possible to ascend directly by broken

ledges. We had barely started when a whizzing, and Conrad’s cry of “Stonefalls!”

made us take to what cover was available. It was the beginning of a

raking fire in which we were all struck, but luckily without damage.

Conrad, calmly saying “Gentlemen, we must move a little to one side,”

relieved the tension; we quickly got out of range, in time to avoid a

heavy bombardment of larger boulders that came banging down over our

intended path and would surely have done for us had we persisted. We

realized afterward that in Conrad’s cool leadership, in emergency, we

had seen one of the finest things produced by mountaineering art.'

So, selecting a new

way, we went on; the ground became increasingly difficult; in one narrow

chimney of thirty-five feet the axes and sacks had to be roped up, and

the last man, looking up at a wrong moment, got the returning coils full

in the face and rather to the detriment of a treasured incisor. Above

the chimney was a low bulge of exposed cliff and the two formed a little

section on which an hour was spent. Easier ledges brought us up to the

glacier and we saw that the ice route would after all have been

decidedly preferable.

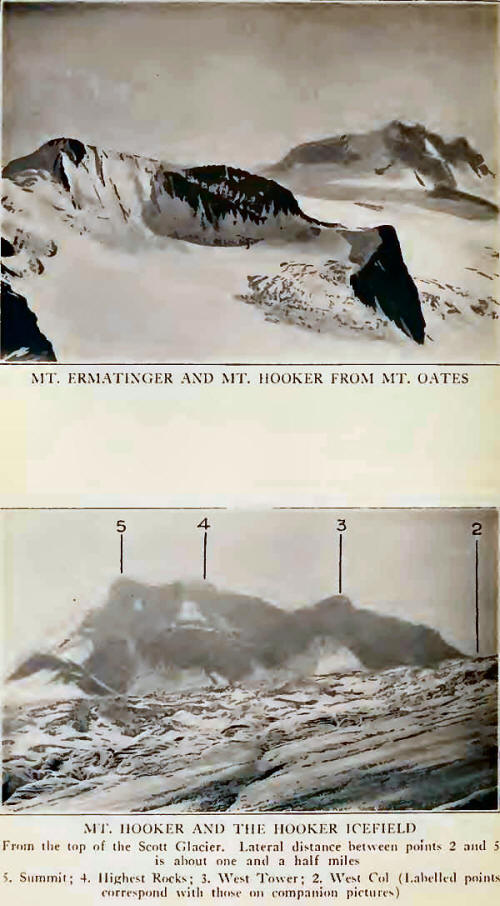

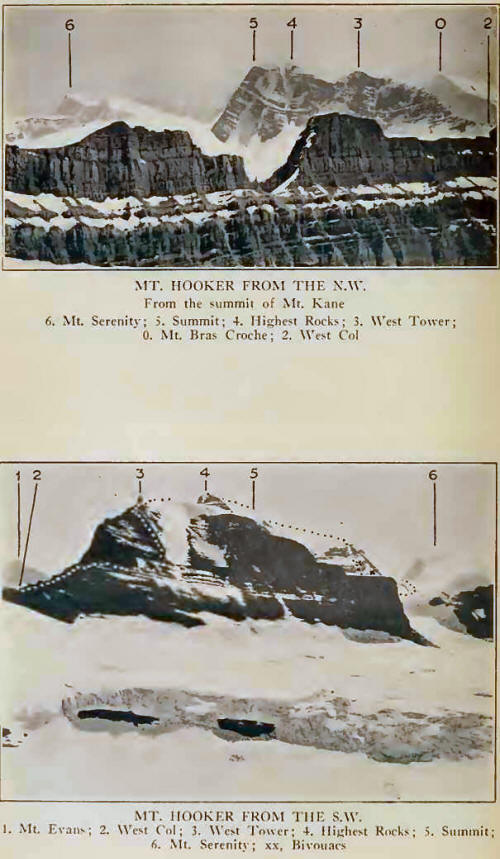

It was eleven o’clock,

and we halted twenty minutes for second breakfast. Mount Hooker was now

in front of us, across an extent of threatening seracs, with northern

cliffs surmounted by a twisted, corniced arete that makes direct ascent

impracticable. The eastern end of the mountain swoops down in a fearful

ice-bulge that seems to overhang, and, even from Mount Oates we had not

seen a plausible way up. And so we chose the western col, knowing it

might give us a long fight; yet we had seen this side from the Kane

Icefield and had found nothing better.

Crossing, not without

some windings through the crevasses, we reached a poorly bridged schrund,

and thence cut forty-five ice-steps to the col. We were at 9300 feet;

the delay was an unexpected one, and it had taken us from 1.45 until

2.30 P. M. to cross the schrund and reach the saddle. The sharp buttress

and tower rising from the col to the west arete were avoided by

traversing and ascending ledges on the south face, above the glaciers

draining to Wood River. Steepening pitches of no great difficulty, close

to the margin of a broad snow-gully, brought us to the mountain’s crest

below the rocky tower near the junction of the middle and western thirds

of the summit arete. It was at this point that I was taking advantage of

some awkward attitudes on the jutting rock, to take a picture of those

ahead of me. But the handling of the rope requires first attention, and

in caring for this a coil touched the open camera. Over it went, rolling

a few feet on the shale and dropping out of sight. It must have fallen

nearly two hundred feet before striking; we looked over the edge and

finally located it. Conrad eventually recovered the splintered box, and

beyond our wildest expectations the lens, shutter, and bellows were

intact. The roll-film had not been thrown out, and, although the picture

last exposed was ruined, the film eventually produced ten perfect

negatives out of twelve exposures. All which is recorded as evidencing

that miracles still occur!

The top of the tower is

shaly, but we avoided it entirely and maintained our altitude by

crossing a broad snow-shoulder extending southward. Here was a really

bad schrund, with flat, thin bridges, and a cornice lip—all which we

treated with marked respect and crossed cautiously on all fours. We

adopted the slow motions of the breast-stroke to this particular

situation, in a way that would have delighted a swim-ming-instructor.

We now gained height on

the main arete, for the first time able to gaze over the northern wall.

We pushed on rapidly, the heavy, compact snow-crust requiring

superficial cutting, and pulled through some small chimneys to the

highest rocks at" half-past seven. From below, we had thought that these

last rock-towers might be the highest point, but, arriving, it was plain

that the snow-crest beyond culminated in two wavelike points, with the

eastern the higher. After making a tiny cairn and leaving a record, we

followed the cornice base to the steep snow of the highest point. It was

eight o’clock, and more than fifteen hours had elapsed since we left

camp. Had David Douglas been with us he might well have thought his

estimate of height was not so far wrong! We anchored, and each,

separately, had a look over the cornice down the north wall to the

icefield. Smoke had just begun to come in from a distant forest-fire in

the direction of Canoe River; we gazed back along the line of dripping,

curling cornices into a red sun—it was as if one were living in the

atmosphere of an early lithograph of “The Alps,” so gaudy it was. Our

more rational interest, however, during the few minutes on the actual

summit (10,782 feet), lay in the fact that we appeared to overtop Mount

Scott. We later confirmed this from Mount Fraser, in the Rampart Group,

and are almost convinced that Hooker is the loftiest peak of the group.1

We would not, however, be understood as placing our eyesight in

competition with the work of the Interprovincial Survey; so for the

present Mount Scott must remain supreme, at least so far as elevation is

concerned.

It was becoming late,

and there was quite evidently insufficient time for us to get off the

mountain and return by the way we had come. We had no desire

*A similar and

independent conclusion was arrived at by the first party to ascend Mount

Serenity. Mr. Carpe informs me that both Palmer and myself were very

much surprised when the survey map came out showing Scott to be higher

than Hooker. It definitely did not make that impression from Serenity. I

should say that it (Mount Scott) seemed lower than Serenity. On

subsequent examination of photographs taken from the Fraser Group the

previous year, however, Scott appears to hide Serenity. Owing to the

late hour at which we reached the top of Serenity, I did not take

instrumental levels on anything. I have no reason to question the

Boundary Commission’s figures.” to return down the rock-wall in the

dark, nor, for that matter, at any time. So we started down a long

snow-shoulder, direct from the peak and descending westward of the

snow-flats which form an irregular pass between Hooker and Serenity. As

we walked down, close to the edge, about sixty feet of cornice split off

and sank silently, its impact far below producing echoing crashes. We

came to the southern extremity of the shoulder without seeing any way

down until the terminal buttress was reached. Following down the margin

of a broad couloir for a little way without trouble, another six hundred

feet of ledges would have taken us to the glacier.

We stopped for a moment

to look at the sunset: the base of the Wood River massif half hidden in

violent mist; the sky tinged with the faint green of arctic twilight,

with a tracery of smoke wisps, grey and red; Clemenceau’s pyramid lifted

into the heavens, with no apparent foundation, a floating thing, serene,

above Bras Croche, with the pearl-pink colorings of an oriental mosque.

.

Perhaps we were

hypnotized; the weather was fine, the view entrancing; we had come down

to the respectable level of 9600 feet, and it was too late to get home.

We planned a night on the rocks. What more natural than when we saw a

perfectly fine cave close at hand, we should make for it? It was roomy

and dry, with doorway rather larger than one would have selected for a

permanent habitation; but altogether not to be sniffed at. There was a

trickle of water only a few feet away, so we consumed most of our

remaining provisions and thought little of it.

We spread our things

about, crawled near to each other, and for a while slept quite

comfortably. And then the trouble began. About midnight there were

flashes of lightning and a rumbling of thunder. Rain fell, soon turning

to snow. A wind came up, gusty and carrying snow into the cave. We were

fairly well protected and kept dry. We got up at four o’clock, with the

first signs of daylight, peering out to find a dense fog which obscured

everything more than fifty feet away. There was a light covering of snow

on the ground and the sleet continued.

Roping, we started

downward, thinking to reach the glacier, round eastward to the pass and

get over to the Scott icefall. We got down to the glacier margin without

much difficulty, although progress was slow and care was required where

the rocks had become icy. The fog was most deceptive and we had trouble

in distinguishing height and pitch of quite simple bits of cliff;

judgment was frequently at fault.

And here we stopped. We

had map and compass and knew our direction; but the Wood River slope of

the Hooker Icefield is so fearfully put together with different levels

of serac and twisted, insinuated buttress, that we simply could not

tell, in the fog, just where the Hooker-Serenity pass might lie. There

were several chances of going astray and wandering over farther on the

Wood River side; which, away from our base of supplies, might be

disastrous. We stamped around in the snow for two hours and attempted to

reach the pass by keeping close to the southern butt' resses of Mount

Hooker. The fog, contrary to expectation, did not break, and the snow

kept coming down.

We were making very

little headway, so at ten o’clock, finding a protected corner, walled in

on three sides and roofed over by a gigantic slab, we decided to wait

out the storm rather than waste energy in fruitless efforts. The wet

snow had soaked us; our food was gone except for some bits of chocolate

and cheese; we had but a little extra clothing, and no means of making

fire. We were at 9300 feet and the snow kept on throughout the day. We

arranged things as well as possible, flooring the cavern with flat

slabs, blocking the open side with boulders and filling the chinks with

snow. Fog hid everything but near objects. We were wet and cold,

beginning to get hungry. All suffered more or less with intermittent

cramps in the thigh and abdominal muscles.

There was a good deal

of shivering, that was hard to conceal, done that night; and quite a bit

of gastric burning, not so evident, but none the less painful— luckily

we could get water in the cave. We had no way of keeping out the fine

blown snow, although we sacrificed the warmth of one rucksack to stop

the largest hole in the wall.

Morning came, a

cheerless dawn, but we had been watching for it. The snow seemed to be

lessening; the fog ebbed and billowed. Just before four o’clock, the

snow ceased; the fog wavered and lifted, so that as we looked out we

could see the ground below us and the way to the pass. We were a stiff

lot, but Conrad made a leap for his boots that startled us. It is hard

work putting on half-frozen shoes, and our guide was first out, pushing

over the snow-crusted boulders in the doorway in his hurry. Miserably

uncomfortable as we were, it was impossible not to think of Samson and

the pillars of the Temple!

Conrad went ahead to

break trail; the ground was not difficult, once the way was seen, and

the rest of us roped and followed. For a few minutes, as we zigzagged

down to the glacier, we could see the lower slopes of Bras Croche, of

Ghost Mountain, across Wood River, and Chisel Peak on Fortress Lake. It

was only a few hundred feet down to the ice and, as we slowly followed

Conrad’s track, the fog closed down gradually. We found Conrad returning

with the good news that he had found the pass and had been nearly to it.

He roped with us and we proceeded as fast as we were able. It began to

snow and blow harder than ever; but we were sure of ourselves. Our faces

and clothing became coated with ice, and hands were cramped through

holding a frozen rope. For an instant we saw a dark stretch of open

water in the lakelet on the pass summit, and everything was hidden

again. The wind blew with great violence, making balance on level ground

an uncertain affair; our tracks were not very straight, but the slope

began to be downward, and we knew we had come across into territory that

was familiar. Through rifts in the mist we recognized the cliffs of

Ermatinger and the eastern ice-bulge of Hooker, and came at last out of

the storm to the main icefall.

The seracs were all

snow-covered; but we would have tackled worse things to get off the

mountain. Conrad’s never-failing craft brought us down in good order to

the unroping place, and we followed the route used for Mount Oates, down

the eastern moraine and the glacier-tongue. Camp was reached shortly

after eleven o’clock. It was July 7th, and we had been out a little more

than fifty-four hours.

Things had been

happening at camp. High on the ice, above the place where we unroped on

descending, we noticed tracks of a man. Dave had become worried when we

did not appear on the second day, and had gone up in an unsuccessful

effort to find us. When we arrived at camp we found that he had left at

2.30 A. M. to ride to Jasper for help. Jack was in camp, mighty glad to

see us, and immediately got us a meal— several perhaps, all in a

row—which we devoured, and then turned in. Jack was sent off with

instructions to ride as fast as possible and turn back any search-party.

We learned later that Dave had ridden the forty-five miles from Scott

Glacier to Jasper in nine hours, secured new horses and, with Phillips,

had sent out a party, including Mr. Val A. Fynn, A. C., with the

Oberland guides Alfred Streich and Hans Kohler. If one were in real

danger, it would be impossible to conceive of a more efficient

live-saving unit.

By fast riding, Jack

turned back the search-party at the Whirlpool tie-camp; and before noon

next day he and Dave had come back to us. They needed sleep and their

horses were used up. The climbing party, after a few hours, recovered

sufficiently to do camp work in the absence of Jack and Dave; and the

impression remains that none of us missed a meal.

By the campfire that

evening, Conrad remarked that Mount Hooker was the most interesting

mountain he had climbed in recent years, and that the summit arete

reminded him of Mount Cook, in New Zealand. There are few Canadian peaks

that he finds worthy of such praise.

Mount Hooker, we

believe, teaches two lessons: first, that it rarely pays to wander over

broken glacier or snowfield in fog; second, that a party in good

condition can wait out a storm of considerable duration. Of the two

things, clothing is more important than food. One night out at the

9000-foot level is plenty; the second is bound to be unpleasant. On

Canadian peaks, however, one is rarely in a position where timber-line

cannot be reached. The storm in which we were caught was of unusual

duration; it continued for a total time of four days, snowing constantly

at higher levels. We were lucky to get out when we did; but we would

have come through eventually, no matter what the weather.

To show that our

climbing party did not return in a hopeless condition, it may be added

that the only damage done was in the shape of superficial frostbite of

the hands, acquired on the third day out, as the result of holding with

wet mittens on a hard-frozen rope. On July 9th, with only one day of

rest, our time in the area being up, the entire outfit made the twenty

miles to the Whirlpool tie-camp, and on the following afternoon was in

Jasper.

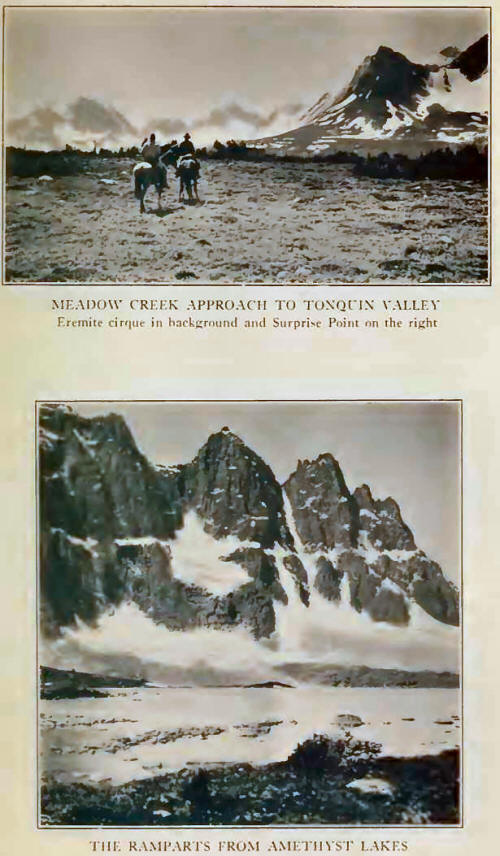

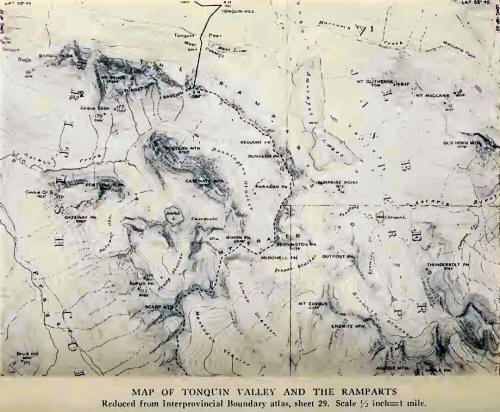

We were en route to the

Rampart Group and had hoped to find a pass through the valley of Simon

Creek over to Tonquin Valley. Because of the amount of spring snow this

was not possible; but on July 11th, we rode from Jasper, by the Miette

and Meadow Creek trails, to Tonquin Hill. Camp at the southern end of

Amethyst Lakes was reached during the following morning and Surprise

Point was climbed later in the day. On July 13th—eight days after the

start for Mount Hooker—we ascended the Fraser Glacier to the

Erebus-Fraser col; crossed to Simon Glacier, the head of the “North

Whirlpool”; made the first-ascent of Simon Peak (10,899 feet), the high

unclimbed summit of Mount Fraser and the loftiest of the Rampart Group,

and then traversed McDonell Peak (10,776 feet), back to camp. This is no

program for an exhausted climbing party! A week later we were climbing

in the Robson Group. But that is another story.

The ascent of Mount

Hooker was the fulfilment of a great desire. To see and to climb Mount

Brown and Mount Hooker will perhaps not be thought of as a remarkable

alpine ambition. They are probably not the peaks Douglas named; in fact

we remain in ignorance as to precisely where he went, what he did, and

what he named during his few hours at Athabaska Pass. The

Interprovincial Survey has unquestionably done the best thing possible

in perpetuating these classic names by applying them to a lovely peak on

either side of the pass. But the ambition to stand upon them is a deeper

thing than it appears; for the naming of peaks by Douglas, and the

over-estimation of altitude— no matter how strange and ludicrous the

mistake may seem; no matter who was at fault in figuring—these things

first led men in search of great Canadian heights. They came from the

far corners of the earth, following pioneer trails, seeking beauty. And

none there was who returned insensitive to the glory of that mountain

vastness.

So we turned back from

Athabaska Pass, on the Whirlpool trail toward the site of Jasper House,

feeling that we too had come under the spell of this overland route of

the long-ago, and, on Mount Hooker at least, had shared a little in its

adventure.

|