|

(The Ascent of Simon Peak)

“Lo! Evening comes on

its wings of darkness. Oh my soul bow down and tame your voice of mutiny

into the hush of evensong. On the banks of the dark a million lights are

lit—those starsj for the worship of Him through His silence; leaning on

the wall of the end of the day, make your peace with the Endless.”

Rabindranath Tagore

The Indians believed that

Jasper Park was the lurking-place of prehistoric monsters. David

Thompson knew of this superstition, as he mentions,1

“Continuing our journey in the afternoon we came on the track of a large

animal, the snow about six inches deep on the ice; I measured it; four

large toes each of four inches in length to each a short claw; the ball

of the foot sunk three inches lower than the toes; the hinder part of

the foot did not mark well, the length fourteen inches, by eight inches

in breadth, walking from north to south, and having passed about six

hours. We were in no humour to follow him: the Men and Indians would

have it to be a young mammoth and I held it to be the track of a large

old grizled Bear; yet the shortness of the nails, the ball of the foot,

and its great size was not that of a Bear, otherwise that of a very

large old Bear, his claws worn away; this the Indians would not allow.”

We ourselves never came

in contact with this unclassified beast, although we had looked for it

throughout our journey to the Mountains of the Whirlpool. We came to the

conclusion that it was a dragon, dwelling in Ostheimer’s interior—his

appetite indicated clearly that he was feeding something beside himself.

But then he may have thought similar things about us; canned peaches

were our special weakness.

It was when we arrived in

Tonquin Valley that we really located the solution of the mystery—the

Ramparts. When one sees that range, curving in sinuous, unbroken length,

with spaced peaks like vertebral spines age-old and worn, it takes but

little imagination to think of it as the dorsal skeleton of some

gigantic creature of ages past. It is the glacier dragon of the Middle

Ages turned to stone. In reality it forms a part of the backbone of a

continent for it is situated on the main Divide; best of all, it is

easily accessible.

Visitors to Jasper Park

are invariably advised to visit Tonquin Valley. Much has been written of

its spectacular scenery—its unique combination of lake, precipice, and

ice—which presents itself with a singular beauty almost unequalled in

alpine regions of North America. From high peaks of the Whirlpool we had

glimpsed its towers and glaciers in the north, and had looked into

misty, forested valleys at Fraser headwaters. We knew that Simon Peak,

the highest elevation of Mount Fraser and the loftiest summit of the

Divide between Fortress Lake and Yellowhead Pass, had yet to be climbed.

And so we went.

The Athabaska2

is an important river even to its very sources. It was not far from

Jasper House that David Douglas, in the spring of 1827, met the

philosophical old guide Jacques Cardinal who, observing that he had no

spirit to offer, turned toward the river and said, “This is my barrel

and it is always running.” The Athabaska flows from two important passes

of the Divide: Athabaska itself and Yellowhead. The Athabaska Pass we

already knew, and a portion of the Yellowhead route was to be followed

on our way over the Meadow Creek trail to Tonquin.

The pass of Yellowhead,

in the old days, was the gateway to the settlements of New Caledonia, as

British Columbia was then known. It assumed importance a few years after

the lower reaches of its great western river had been explored by Simon

Fraser, John Stuart, and Jules Quesnel, in 1808. The fur traffic through

the pass had become so extensive that, about 1820, the pass was commonly

known as Leather Pass. Then came the gold rushes to the Cariboo, in 1861

and 1862, when the pass was used by crowds of adventurers on their way

to the North Thompson River. Among the earliest travellers who came

through Yellowhead, bound for the North Thompson and Kamloops, were

Viscount Milton and Doctor Cheadle, in the summer of 1863. Accompanied

by the wandering eccentric, Eugene O’Beirne—the mysterious Mr. O’B.—and

a one-armed Assiniboine guide with his courageous squaw, these gentlemen

were the first to describe Mount Robson, and, indeed, much of the

Yellowhead region. Their book, The North-West Passage by Land, among

many interesting things, contains their dramatic discovery of the

Headless Indian, who no doubt perished on the way to Cariboo.

The story4 and its sequel

are worth re-telling: “The corpse was in a sitting posture, with the

legs crossed, bending forward over the ashes of a miserable fire of

small sticks. The ghastly figure was headless, and the cervical

vertebrae projected dry and bare; the skin brown and shrivelled,

stretched like parchment tightly over the bony framework, so that the

ribs showed through distinctly prominent; the cavity of the chest and

abdomen was filled with the exuvia of chrysales, and the arms and legs

resembled those of a mummy. The clothes, consisting of woollen shirt and

leggings, with a tattered blanket, still hung round the shrunken form.”

Nine years later, in 1872, several hundred yards up the bank of the

river, the head was found by members of the T. Party, Canadian Pacific

Survey. They buried the head with the body; but it was exhumed later in

the year by Dr. Moren of Sandford Fleming’s Pacific Expedition. The

skull, placed in the Canadian Pacific offices in Ottawa, was destroyed

by fire in 1873.

Poor old Shuswap cranium;

what a wandering career it had! But since we ourselves were starting out

on the Yellowhead trail, it is scarcely to be wondered at that our own

heads were filled with thoughts of these strange events that transpired

within the memory of our fathers.

Jasper was our

starting-point for Tonquin Valley; and, on the morning of July 11th, the

day immediately following our return from Athabaska Pass, we headed the

pack-train westward into Miette Valley toward Yellowhead. An Iroquois

hunter was this Tete Jaune, whose original Cache was not at the station

of the Canadian National now bearing the name, but at the mouth of the

Grand Fork of the Fraser. And there he hid the furs he obtained on the

western slope before bringing them to Fraser. On the day of the

starting, furs would have been useless as skis; we were riding in our

shirt-sleeves and the sun beat down unmercifully. Worst of all, when we

wanted a drink we had to scramble down the steep bank to the river.

Still we were in no danger of having a recurrence of the sad misfortune

which befell Sandford Fleming: “The Chief’s bag got a crush against a

rock, and his flask, that held a drop of brandy carefully preserved for

the next plum-pudding, was broken. It was hard, but on an expedition

like this the most serious losses are taken calmly and soon forgotten.”

We should have been less philosophical; but now, sagging low in our

saddles, with dust of the trail rising in a golden cloud and obscuring

all but the heads and the packs of horses behind us— with water close at

hand, we were just too lazy to climb down and get it. As this was our

third consecutive day of long riding, we felt our lethargy was

excusable.

We had looked backward to

Mount Edith Cavell— “La Montagne de la grande traverse”—southward and

closing the Athabaska Valley, with a face “so white with snow that it

looked like a sheet suspended from the heavens.” It was hidden as we

crossed an old trestle above the sparkling Miette and the horses plodded

on beyond. We eventually came near to Geikie station where begins the

trail up Meadow Creek, cut out by the park rangers in 1922. A

beautifully engineered affair, it rises first in breathlessly steep

zigzags and curves for a thousand feet above the Miette to an upper

forested level that swings into the side-hill beyond a canyon in the

creek bottom. Snow peaks are seen across the valley, a brilliant little

group centered about Mount Majestic; we gazed upon them first from the

base of Roche Noir as the horses splashed through a stream near the

mouth of Crescent Creek. A few minutes later we climbed again to higher

slopes where the trail leaves the darkness of mossy nooks and giant

trees, and emerges in thinning timber to willow meadows near Tonquin

Hill. From camp beside a gurgling brook we gazed out to the northern

outposts of the Ramparts—Bastion, Turret, and Geikie—fantastic wedges

and pinnacles, tinged with the metallic glow of light through the

western passes.

That night we were

entertained by the amusing story which Conrad had to tell of a

mountaineering parson with whom he had travelled. It seems that the

parson was much worried about the future salvation of our guide’s soul,

and tried to convert him to the fold. He said one day, “Conrad, when you

have been in a tight place on the mountains, has the Angel of the Lord

never stood by you and told you to be unafraid?” Con, who is an amiable,

open-minded philosopher, replied that no such angelic visitation had

ever occurred, but that he was ever hoping for such a miracle. The

parson earnestly advised him to pray for it, adding, “I am sure that

there are mountains in the after-world. I have always desired to make

the ascent of the Matterhorn, a feat which my financial condition has

prevented. The after-world is, therefore, made up for different degrees

of attainment. If I live my life righteously, I shall perhaps find my

Matterhorn in the world to come. You, remaining unbeliever, will surely

pass eternity on a prairie.”

The doom sounded harsh to

Conrad. A few days later, on the trail, a straying horse snagged a pack

and fell bodily into the creek. Much to the surprise of Conrad, the

parson burst into expressions of profanity that are seldom associated

with the clergy. Con wheeled his horse and rode back. “Shake hands,

parson,” he called, “sometimes I think you are almost a man. I don’t

know for sure how far down in dot after-world you come; but chust be

yourself, and maybe yet we climb dot Matterhorn together!”

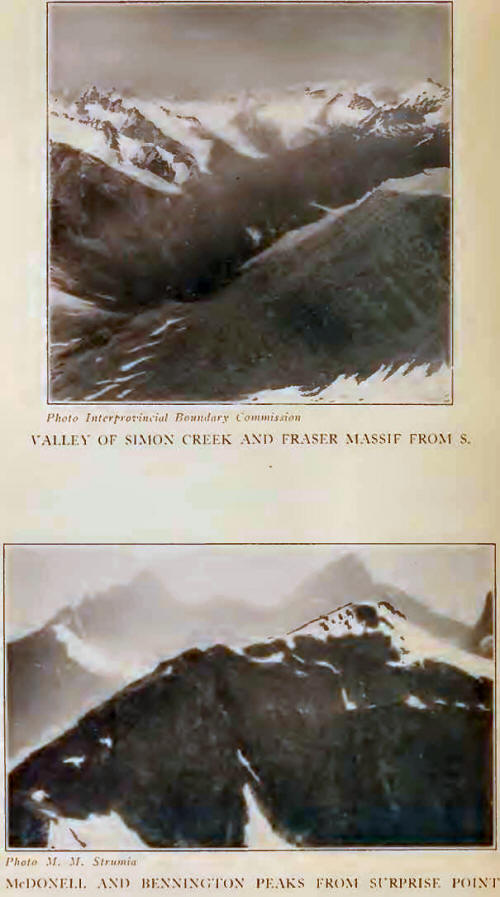

This bit of alpine humour

may relieve a few paragraphs of topographical explanation, which will

make clearer what follows. The Rampart Group forms the chief mountain

uplift of the Continental Divide between Athabaska and Yellowhead

Passes. Its western slopes are drained by the head of Fraser River and

its tributary creeks, Geikie and Tonquin. On the east, Simon Creek,

Astoria River, Maccarib and Meadow Creeks flow into the Athabaska

system.

Following the Divide

northward from Whirlpool Pass (5936 feet), the first peaks of any

importance form the western wall of the basin in which a number of

glaciers converge, like wheel-spokes, at the head of Simon Creek—the

“North Whirlpool.” These peaks are Whitecrow (9288 feet), Blackrock

(9580 feet), Mastodon (9800 feet), and Scarp (9900 feet). All are

attractive rocky summits, with long radiating ridges and interconnected

snowfields. Just east of the Divide, Needle Peak (9668 feet), requires

special mention because it will no doubt afford some very interesting

and spectacular work for ambitious climbers of the future. It is a

slender flake of rock, with broad base flanking the mouth of Simon

Creek; the best approach is by way of Whirlpool River in two long days

from Jasper.

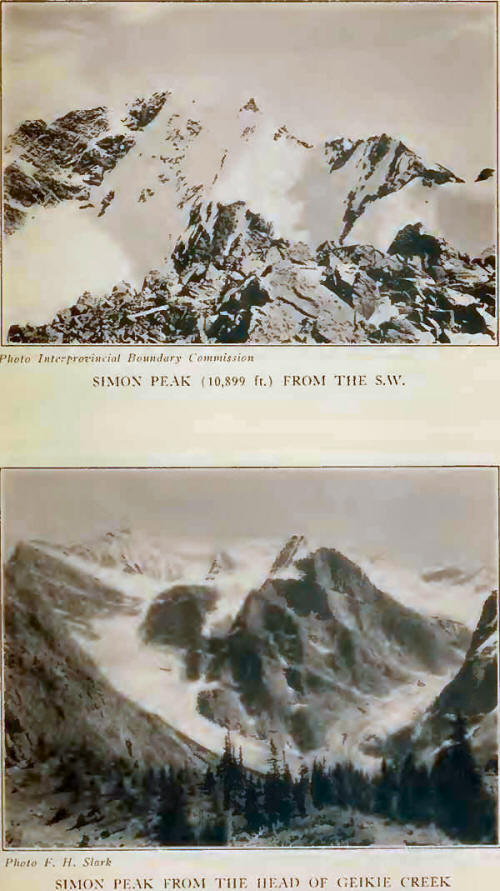

At the head of Simon

Creek the Divide rises to Mount Fraser, the culminating elevation of the

group, and over its three peaks6—Simon (10,899 feet), Mc-Donell (10,776

feet), and Bennington (10,726 feet) — to the rampart-wall of aiguilles

beyond.

The Fraser Glacier, on

the southeast side of the Fraser massif, occupies a pass between the

head of Astoria River and the “North Whirlpool,” Simon and Mastodon

Glaciers forming the chief sources of Simon Creek, although a tongue

from the Fraser Glacier also enters its headwater. The main drainage

from the Fraser Glacier, however, is into Astoria River.

Simon Fraser (1776-1862)

was born in Bennington, Vermont. The Fraser River was named for him late

in 1808, by officers of the North-West Company, at which time he was

Superintendent of New Caledonia. His wife was the daughter of Col. Allan

Mc-Donell, of Dundas County, Ontario.

Southeastward from the

Fraser neve there extends an interesting and unvisited group of peaks

bounding the Eremite Glacier cirque. These peaks are Outpost, Erebus

(10,234 feet), Eremite (9500 feet), Alcove, and Angle, all of them lying

in Alberta, within easy climbing distance from Surprise Point and

Amethyst Lakes.

From Mount Fraser the

Divide circles over the sheer wall of the Ramparts—Paragon (9800 feet),

Dungeon (10,000 feet), Redoubt (10,200 feet), and Bastion (9812

feet)—dropping abruptly to Tonquin Pass (6393 feet), the crest of the

range then swinging westward into British Columbia and supporting the

precipitous trio: Turret (10,200 feet), Geikie (10,854 feet), and

Barbican (10,100 feet).

The headwaters of Astoria

River are derived in part from Chrome Lake, into which flow rushing

streams from the Eremite and Fraser Glaciers; but a somewhat larger

creek rises in the Amethyst Lakes, two lovely bodies of water closely

connected with one another and lying close below the stupendous east

wall of the Ramparts.

Moat Lake is finely

situated in the eastern hollow of Tonquin Pass and sends a stream to

join with a northern outflow from Amethyst Lakes; and, in an expanse of

willow-covered, marshy ground, drains both to Meadow and Maccarib

Creeks.

In the western cirque of

the Ramparts, glaciers streaming from Mount Fraser drain to Geikie

Creek. Scarp and Casemate Glaciers slope off abruptly to" Icefall Lake;

while the long, winding Bennington Glacier is separated from them by the

jagged rock arete extending northwest from Simon Peak and supporting the

dark towers of Casemate (10,160 feet), and Postern (9720 feet).

In the central part of

Jasper Park, just west of the Whirlpool-Athabaska junction, Mount Edith

Cavell (11,033 feet), had been climbed by Messrs. Gilmour and Holway in

1915. In the same year a portion of the Park was surveyed by Bridgland,

but no station except Surprise Point was made in the Rampart-Fraser

range. No climbing party left a record on this portion of the

Continental Divide until 1919, when Messrs. Carpe, Chapman, and Palmer,

from campground at the southern end of Amethyst Lakes, made

first-ascents of McDonell and Paragon. They were the first to see Simon

Peak and the Bennington Glacier at close range and to appreciate their

grandeur and importance. Mr. Carpe, at that time, obtained an altitude

of 10,900 feet for Simon Peak and the party recognized it as the main

apex of the massif. It was not then thought of as a part of Mount Fraser

because the Bridgland map had applied the name “Mount Fraser”

specifically to the east peak. The use of “Mount Fraser” to cover the

whole massif—Simon, McDonell, Bennington—is a recent development, and

has been incorporated with the maps of the Interprovincial Survey.

Members of the latter survey, in 1921, occupied many high points as

stations, including Beacon (9795 feet), Whitecrow (9288 feet), and Rufus

(9053 feet) ; and connected the triangulation with the earlier Bridgland

survey of the central area of the Park.

In the fourth volume of

Modern Painters, John Ruskin expressed his doubts as to whether we live

in a world just in its prime or in the ruins of former Paradise. One

realizes instinctively in the valley of Tonquin that the carving of its

great rock spires is still in the formative stage. The work is still

going on; the mountains are but roughly hewn out, with an

impressionistic technique as fantastic as it is fanciful. The great

slopes of sharp chips and ragged blocks indicate plainly that Nature has

but shaped out the plan; there is as yet nothing of the soft smoothness

of finished work.

It was a gay day, bright

with sunshine, when we rode the trail toward Amethyst Lakes. The

surveyors who christened the Ramparts thought of it as a castellated

range and bestowed upon the peaks the mediaeval names suggested by their

counterparts—Turret, Bastion, Redoubt, Dungeon, Postern, and Casemate.

But the crest is so sinuous and angulated that, as we looked toward it

from across the valley floor, we felt that the analogy to the spiny

remains of a petrified dinosaur or some similar creature was an equally

good one. Certainly there were never any man-built castles in Jasper

Park; but did we not know from the Indian stories that it had always

been the abode of dragons?

In the valley of Maccarib

Creek, on a sloping alp-land, is a tiny cabin. Freshly painted with a

bright red roof, it serves as the palatial home of Ranger Goodair—that

is, when he is at home. We had met him on the Whirlpool River, where he

had been of service to us in helping cut trail during our attempt to

reach the head of Divergence Creek and the base of Mount Fryatt. A

quiet, pleasant man, he had had the usual interesting career of those

whom one runs across in the far places. Studying medicine in London, he

enlisted and went to Africa during the Boer War, remaining afterward in

the South African diamond fields, wandering as a prospector to strange

corners of the earth, and at last finding a life in the Canadian

wilderness that pleased and held him. We could quite understand it, and

not without a touch of envy.

We followed the trail

through flowering meadows— heather and paintbrush—on the shore of

Amethyst Lakes; broad sheets of translucent blue reflecting the steep

buttresses and crescentic hanging glaciers of Redoubt and Dungeon. There

is one conspicuous horizontal snowy ledge, mid-high in the wall and

continuous with scarcely a break save where icy gullies cut through at

right angles from the high notches in the jagged crest-line. In a little

while camp was pitched in the trees near the southern margin of the

lakes, and we eagerly awaited Jack’s announcement that luncheon was

served. I dare not tell you what we would have for breakfast or dinner,

but lunch in those days might include pork-and-beans, fried potatoes,

buffalo-pemmican, salmon, bannock with jam, and dried fruit. There was

no serving of courses, everything was on one’s plate at once, and

nothing ever left over. .

Surprise Point is an

amusing little pinnacle that rises above the camping place to a height

of 7873 feet. It looks so easy, but is really quite a scramble if one

tries it in moccasins and with each hand encumbered by a camera. Strumia

and I climbed up during the afternoon, in something less than two hours,

although we made frequent stops to photograph some queer little rickety

towers of the ridge, that looked for all the world as if a giant’s child

had been playing at building blocks and had finally disjointed his

construction with a push. There is not much room on the summit, but we

found a ledge where snow was melting and a place where we could stretch

out for a snooze on the warm rocks. We stayed there for more than three

hours in rapt absorption of the lovely overlook on peak, meadow, and

winding stream. Tonquin Valley is wide and almost filled by the

glistening stretches of the two Amethyst Lakes, whose waters are

connected only by a narrow channel between two little wooded peninsulas.

The lakes are larger than many we had seen, and with their flat,

meadowed shores it is almost as if a bit of the prairie had been

transported and placed there to contrast with the Ramparts’ wall. It was

all spread below us like a map, and only when the westward sun threw a

dark serrated silhouette of the range down upon the water did we tear

ourselves away and race down to the campfire.

Simon Peak, although it

is the culminating height in the group, is most retiring and quite

invisible from campground at Surprise Point. Next morning, July 13th, we

left at half-past five with the idea of finding and climbing it if we

could. An old game trail was followed through the dense forest to the

ancient moraine and the stream which comes from the Fraser Glacier. We

entered a shadowed glen where the bed of the creek is somewhat wider and

the waters spread into limpid pools that perfectly reflect the

symmetrical outlines of Bennington, towering above a line of stately

pines. Unfortunately the ground is marshy and forms a breeding place for

mosquitoes, which followed us in clouds until the breeze from the ice

drove them away.

Hurrying up some rising

grassy slopes we were soon among the enormous morainal blocks below the

glacier, and in a few minutes had rounded a tiny blue marginal lake to

the ice itself. Past a corner of Outpost the circle of little peaks

bounding Eremite Glacier presented themselves in snowy line. Eastward we

looked down upon the curious yellow brilliancy of Chrome Lake, and into

the Astoria Valley where Mount Edith Cavell raises a shaly, snowless

gable to a sharp point wholly unlike the great white face one sees from

Jasper. The Fraser tongue is almost unbroken and we rapidly gained

height on long slopes of snow and moraine. A little to the south rises

Erebus, in a series of steep cliffs and receding ridges in step-like

formation that would make direct attack a difficult procedure.

Foreshortening makes the peak seem very sheer, but toward Simon Creek,

southwesterly, it breaks down into an easy gradient of shaly strata.

We had heard that Simon

Peak possessed a formidable ice-crest, and for that reason it had seemed

best to reconnoitre a little in order to spy out a satisfactory route.

In two hours and a half from camp we reached the nearly level

snow-plateau on the Erebus-Fraser saddle and could look over to the

radiating glaciers at the head of the “North Whirlpool.” It was quite

unnecessary to make use of climbing-rope and I went on ahead to a higher

slope whence I could photograph the rest of the party on a wind-blown

snowy ridge below, with Mount Erebus for a background. Distantly in the

south, the Scott Group and the mountains near Athabaska Pass were

visible through a thin veil of forest-fire smoke. We stopped for a few

minutes and then crossed two small snow basins to the head of Simon

Glacier. We sat down for lunch in the shadow of a curious little tower,

perhaps forty feet high and looking for all the world like a “pill-box”

of wartime days. It was a blunt needle with steep walls which nearly

aroused us into an attempt to climb it. Food, however, proved more

enticing.

The actual peak of Simon

was still hidden, but we could now see that it would be possible to get

onto the glacier, cross to its head and ascend steep slopes toward the

col between our objective and McDonell Peak. This plan was duly followed

out and we were soon a considerable distance up the snow. Due care was

necessary in avoiding the base of a small icefall which enters the

snowfield at the edge of our proposed route, and blocks of blue ice

imbedded far out on the snow gave indication that little avalanches

sometimes came down. We crossed a deep schrund below a rocky wall, over

a bridge that was narrow and steep, and then mounted steadily over

down-tilting strata where water cascaded down and filled our sleeves if

we were not careful in our choice of hand-holds. There was a gully in

the margin of the icefall where a careful watch was made to avoid the

flakes of shale which frequently scaled down and sailed over a rocky

bench to lower snows.

It was soon possible to

cross above the top of the fall and take to the rocks, after which we

made good time to the ridge above. For the first time we now saw Simon

Peak, a little to the north, icy, and with superb frozen cornices

overhanging the gorge of Bennington Glacier. The rope became a real

necessity; Conrad cut steps along the southern slope where the ice

fragment swished down and vanished. There were patches of quite hard

ice, slowing our progress, and more than a hundred steps were made to

the first snow point of the final crest. Beyond us lay a higher cornice,

and then a short level of rocks and shale forming the summit; it was

just half-past one when we arrived and took off the rope. The

difficulties had been less than we expected.

It was a pleasurable

surprise to find a rock outcrop on the very highest point of our

mountain, and we sat down in a comfortable spot to have lunch. It was

not the best of days for a distant view, as smoke hid many of the far

peaks that we had hoped to see. Most spectacular, however, was the gorge

of Bennington Glacier. Formed by the snows that lie in the northern

cirque of Mount Fraser’s three peaks, it winds sinuously below the

barren west wall of the Ramparts and disappears around the corner of

Casemate—the lowest portion of visible ice being more than four thousand

feet below our viewpoint. The glacier is more than three miles long and

gives rise to Geikie Creek flowing to Fraser River; the long northern

arete of Simon Peak walls the ice on the west and plunges down in

snow-powdered precipices and broken ridges that support the gigantic

towers of Casemate and Postern. Beyond the muddy waters of Icefall Lake

are two smaller pools of a clear, transparent blue, and on the meadows

across Geikie Creek we discovered the tents of Messrs. Fynn, Geddes and

Wates who were carrying out a mountaineering campaign in the vicinity.

Above their camping-place

rises Mount Geikie; a tremendous grim wall it is, seared and fissured by

ice-filled couloirs, and surmounted by two fine towers sprinkled with

new snow. We thought that the rocks would be scarcely dry enough for

climbing, and were pleasantly surprised to learn that a successful

ascent was achieved only a few days later.5

During our little stay on the highest point of Mount Fraser we gazed at

Geikie’s fascinating crags and could scarcely believe that our summit

was by a few feet the loftier.

It was now quite plain

that nothing of difficulty intervened between Simon and McDonell Peak;

so rather than retrace our roundabout route, we built a cairn, walked

back in the ice-steps, and traversed McDonell. We were just one hour

between summits, Strumia leading up the ridge on steep crags where every

hold was firm and belays for the rope were found wherever required. We

had some thought of going on and adding the unclimbed Bennington Peak to

our bag; but it looked long and not too interesting; storm clouds were

blowing over and we decided to go on down. Besides it was half-past

three and Ostheimer, as usual, was beginning to think of supper.

Long slopes of scree and

shale lean down to the Fraser Glacier; we took off the rope and were

soon far below. Peals of thunder were heard in the north, and a shower

of rain swept by as we left the ice. At five o’clock we were once more

among the mosquitoes— Con heard them buzzing nearly half a mile away and

put a turn of the rope about his ice-axe lest they carry it off—and

spent a miserable hour fighting them in the woods below our camp. On

arrival we found Jack and Dave stretched on the grass, looking through

the binoculars toward the Astoria meadows. What they at first had

thought was a grizzly turned out to be a cariboo; and on watching we

counted no less than twenty-five of them feeding and slowly moving

across the grassy slopes. As we turned toward the fire, drawn by the

appetizing odors from Jack’s cookery, the clouds were breaking above the

Ramparts and a broad shaft of golden light formed a bright pattern on

the Eremite Glacier.

Early in the morning we

broke camp and returned to Moat Lake, a ride of some three hours. The

sky was overcast and the spires of the Ramparts were all hidden in

trailing mist. Our tents were set up near the little ponds on the summit

of Tonquin Pass, with a frontal view of the cliffs of Bastion and

Turret. During the afternoon Conrad and Strumia went over to examine the

northern wall of Geikie, but were able to see little of the upper

portion because of low clouds that swirled about without lifting. Below

the Turret pinnacle is a narrow gully, with broad, funnel-shaped top

which collects the stones that come rattling and banging down night and

day. Dave told me that the Indians for generations had known of this

place of “mountain thunder.” Sunset glow cast crimson and purple lights

on the buttresses of Geikie and Barbican, with sulphur light suffusing

the transparent mists through which the higher ridges were occasionally

revealed.

Although the next day

came with a grey dawn, Conrad and Strumia went out for a climb on

Bastion. Dave rode off to explore a pass leading toward Yellowhead. Jack

and I watched the mountaineers cut over a steep slope of snow high up

and disappear into the hollow beyond. A lazy afternoon was spent in

photographing groups of the pack-horses and their reflections in calm

pools near Tonquin Pass. The climbers were back in time for supper,

having reached a lofty notch through which they looked down upon

Bennington Glacier. The final wedge, like a huge stone spade, had been

out of the question under such weather conditions and with the limited

time at their disposal; the path was hidden in fog and there was nothing

to do but come down. As they neared camp they came upon a huge old

antlered cariboo within a range of twenty feet; they held still, but the

great beast scented them and moved off snorting and pawing the ground.

It was our last night in

camp with the outfit, and as usual the weather showed signs of immediate

clearing. My conviction is that Conrad is the reincarnation of

Scheherazade, with several hundred extra yarns thrown in. Would that we

had the wit to reproduce his own inimitable style! At all events he was

in great form that evening, and treated us to tales of startling

adventure: snake-collecting in Egypt, sheep-herding in Australia,

gold-washing in the Northwest, wanderings in the South Seas, hunting in

the Siberian Altai. The most beautiful place in the world, he believes,

is the island of Madeira; there he would like to spend a little of his

old age before retiring to a cottage in the Tyrol. And the most

interesting place of all is New Zealand. Among the many strange things

which befell him there, none had a more amusing sequel than his

experiment in spiritualism:

During a long climbing

tour in the New Zealand Alps, Conrad had a mystical lady under his

guidance who often attempted to communicate with spirits of the

departed. Her guide appearing interested, she imparted much information,

and after his return to Canada sent him a considerable amount of

literature on the subject. So one night, Con told us, he attempted to

mesmerize himself into a trance. Placing a lighted candle on the foot of

the bed, he lay down and gazed steadily at the flame. He was on the

point of arriving at that exalted state when his spirit would be free of

its body, when his big toes suddenly received a horrible scorching from

hot candle-grease. The candle fell over and bedding blazed up. With a

fearful yell he made a dive for a bucket of water, extinguished the

conflagration, but ruined the floor and almost drowned his wife in the

room below! We were almost hysterical with mirth before the end of the

story and narrowly escaped rolling into our own fire.

Gradually recovering our

equanimity we noticed that from behind Maccarib and Oldhorn, beyond the

little lakes, a full moon had come up to light the shadowy walls of the

Ramparts. Pinnacle after pinnacle caught up a gleaming moonbeam as if

hidden sprites were racing along the ridges and touching them with

torches into a silver glow. Slowly rose the moon; not in solemn

grandeur, but rather with full face smiling as if in sympathy with our

merriment. A wind from the Tonquin Pass was gently moving the pine-tops;

there was a tinkling of bells as our horses wandered across the meadows. |