|

“No game was ever

worth a rap For a rational man to play,

Into which no accident, no mishap Could possibly find a way ”

Everest Expedition,

1924

It was during my first

season of real mountaineering in the Northwest that I saw Mount Robson.

Our climbing had been in widely separated regions that summer—in the

Rockies, along the Canadian Pacific; in the Selkirk Range. We had

tramped through the Cascades, voyaged up the coast in a tiny steamer to

the islands of southeastern Alaska, and had camped by the glaciers that

come down to Taku and Atlin. It was late in the fall when we started

eastward from Prince Rupert, on the Grand Trunk road; there was a

delightful crispness in the clear September air, sharpening the outlines

of jagged little peaks of the Coast Range that lifted above the dim

violet of distant, forested slopes, and the nearer brilliance of

yellowed birch and poplar banking the Skeena River.

And then, for a day,

our train had followed the canyon of the Fraser, past the hilly mining

country near Prince George; and, at evening, we were on the bend near

Tete Jaune, with the glorious massif of Robson towering afar. Clouds

were gathering, and the vision was soon gone; but we had one splendid

moment when the mountain’s crest was golden, above a mist-wreathed base.

Of course I had read

about the mountain before. It was first described by Lord Milton and Dr.

Cheadle, early travellers through the North Thompson Valley, in their

book, The North-West Passage by Land. “On every side,” we are told,1

“the snowy heads of mighty hills crowded round, whilst, immediately

behind us, a giant among giants, and immeasurably supreme, rose Robsons’

peak. This magnificent mountain is of conical form, glacier-clothed, and

rugged. When we first caught sight of it, a shroud of mist partially

enveloped the summit, but this presently rolled away, and we saw its

upper portion dimmed by a necklace of light feathery clouds, beyond

which its pointed apex of ice, glittering in the morning sun, shot up

far into the blue heaven above, to a height of probably 10,000 or 15,000

feet. It was a glorious sight, and one which the Shuswaps of The Cache

assured us had rarely been seen by human eyes, the summit being

generally hidden by clouds.”

The very origin of the

mountain’s name is lost in the past; but the Indians had their own names

for it, long before the arrival of white men.

Mr. H. J. Moberly,

factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, gives the following information in

regard to the name of the mountain: “Years before the Hudson’s Bay Co.

and the Nor’-West Co. joined (1821), it was the custom for the Nor’-West

Co. to outfit a party for a two years’ trip, hunting and trading. They

went west and north, even as far as the border of California. One party,

under the charge of Peter S. Ogden, some two hundred men, chiefly

Iroquois and French Canadians. When west of the Rockies, he scattered

his hunters in different parties under the charge of a foreman, to hunt

for the season. One of his camps, under the charge of a man named

Robson, was somewhere in the vicinity of this mountain, and it was the

rallying point where all other parties came together for their return

east.” wyn,1 Director of the Geological Survey

of Canada, as early as 1871, reported that the Indians told him their

name for the mountain signified “The lines in the rocks.” As Dr. Dawson,

in a paper presented before the Royal Society of Canada in 1891, informs

us,2 “The Kamloops Indians affirm, that the

very highest mountain they know is on the north side of the valley at

the Tete Jaune Cache, about ten miles from the valley. This is named Y

uh-hai-has-kun, from the appearance of a spiral road running up it. No

one has ever been known to reach the top, though a former chief of

Tsuk-tsuk-kwalk, on the North Thompson was near the top once while

hunting goat. When he realized how high he was he became frightened and

returned.” The Cree Indians call Robson simply “The Big Mountain,” but

this seems to be a modernism; old men, with whom I have talked, say that

their tribe never had a special name for the peak.

Mount Robson is the

highest summit in the Rockies of Canada; but, like many a lesser peak,

its height has diminished with recent measurements. The first

triangulation, that of McEvoy, resulted in a figure of 13,700 feet; but

the more recent determination of the Interprovincial Boundary Commission

has brought this down to 12,972 feet. Thus an old illusion is shattered,

and no peak of the Rockies of Canada attains thirteen thousand feet.

Dark was the night when

the train pulled through Yellowhead Pass and down to Jasper. This was in

the days before hotels, and one obtained lodging in rooms above the

grocery-store; or, if the vacation was an extended one, in the “tent

city” on Lake Beauvert, where the attractive Lodge of the Canadian

National is now situated. The Grand Trunk was then running a through

train to Prince Rupert only on alternate days; so in order to go back

next day for a better view of Mount Robson—as I had decided to do—it was

necessary to get permission to ride on the freight. There was less

trouble about it at that time than there is now, and I know of no more

delightful way of seeing the mountains—I refer of course to the railway

zone— than from the caboose of a slow-moving “side-door pullman.” If the

engineer happened to be very good-natured, you rode up front on the

cow-catcher; with every opportunity for photographs, and, perhaps, if

there was a delay in waiting for an express to pass, the chance to go

fishing with the train-crew.

Roadbeds of the

mountain area, recently constructed, were not yet equal to the

rolling-stock which passed over them. We started off early in the

morning, up the valley of the sun-flecked Miette, and on through

Yellowhead Pass. Standing on the rear platform, looking across at the

heights of Mount Fitz-william,5 we were startled by a crashing and

grinding.

Jumping off, we saw

that a spread rail and a buckled truck had wrecked the whole train

ahead, and that several huge loads of groceries had spilled down the

embankment of the Fraser River, with more than one car slanted out on a

precarious angle and threatening to follow.

So the engineer wired

for a wrecking crew, and the trainmen got out their fishing-tackle. We

were only half way to Robson, and I walked back along the tracks to

Lucerne to await another train that was due on the Canadian Northern

road. I have never regretted this pleasant stroll; there was no reason

for hurrying—a small boy informed me that my train would be four hours

late—and the time was passed on the lake shore, where ducks were

swimming and the placid water mirrored the peaks of Yellowhead.

It was again dark when

we started westward. In a few minutes, across the Fraser, we could see

the fires lit by the train crew to assist them in clearing the wreck of

our freight. The night was calm and clear, and a red, waning moon rose

over the hilltops as we neared Moose Lake and the Rainbow Range. I had

no very accurate idea as to the exact location of Mount Robson, or just

how one would set about getting near to it. We had seen it from Tete

Jaune, and realized that the mountain lay north of the Fraser; but of

the trails through the intervening valleys and forests we knew nothing.

Still I knew that I could again see it from the railroad, and under

better weather conditions; I thought it might be possible to find a way

across the river. I was quite determined to go as close as possible to

that loftiest of mountains.

It is a strange and

interesting little adventure to look back upon. I knew practically

nothing of the ways of the trail; I had no equipment save a camera and a

rucksack filled with provisions; it was late in the month of September.

The train slowed down to let me off by the box-car filled with hay,

which then served as Robson Station. It was midnight; I was alone, and a

cold wind blowing from the west and the rising moon were my sole

companions when the train had passed around a bend and out of sight. I

could not see that much was to be gained in waiting for morning to come;

it was almost impossible to restrain my eagerness for a sight of the

mountain. And so I started off along the tracks in the semi-darkness.

Youth does such things.

And suddenly the vision

appeared! Mist and vapour play strange tricks with one’s judgment of

size and distance—moonlight affects it to perhaps an even greater

degree. I had walked several hundred yards along the tracks, and then I

stopped, scarcely believing what I saw. There it was; Robson, “the

mountain of the spiral road,” seeming to touch the very heavens, flooded

with soft light and gleaming like molten silver. The light of the moon

seemed to become tangible, as if one were swimming in a luminescent haze

that altered and exaggerated refraction. I had seen higher peaks before,

and have since stood on the summits of many, but nothing has ever

equalled the impression of stupendous height that Robson gave on that

starlit night of years ago. It seemed to me then as if I were gazing up

to the throne of some Divinity; although maturer years have somewhat

tempered this idea to the thought that there is merely a feminine

quality in some mountains which makes them best seen at night.

But certainly that did

not enter my head at the time. I sat down on a trestle and dangled my

legs over the side, and looked and looked. But contemplation of the

sublime cannot maintain the body at an even temperature on a freezing

night. I got up and moved slowly along, rubbing my eyes and still half

afraid they were deceiving me. And then a piece of luck: a bobbing

twinkling light along the rails ahead. It was carried by Bert Wilkins,

an outfitter then working for Donald Phillips, who had come out looking

for me. I had met him for a moment when the train came through a few

days before and had told him that I would try to come back. He still had

some horses down in the Grand Forks and in a few minutes we had arranged

for a pack-train trip to Robson Pass. I was glad at the thought of

having company who knew the way.

The keeper of a

section-house put us up for the night, and next morning we went down for

the horses. There was then no bridge over the Fraser; but a logjam, long

since departed, afforded a place of crossing. We rounded up the cayuses,

and finished a tremendous breakfast of bear meat, potatoes and steaming

coffee. On the preceding day Bert had shot a large black bear on a

nearby berry-slide, and the hide was now nailed up on the door of the

shack. A “homesteader,” whose section is in the angle of the Grand

Forks, came over and joined us as cook. We were off shortly after seven

o’clock, three riders and two pack-horses, not long after the first

sunbeams reached us across the high hills bordering the Fraser. One

crosses the old freight road and, entering the woods, leaves

civilization behind.

The trail is

unforgetable in its beauty, with spruce and cedar trees straight and

perfect above a carpet of berries, fern-brakes, and devil’s club;

tropically luxuriant. The stream descends in cascades and rapids, with

the southern cliffs of Robson almost above one’s head. Far behind, in

the direction of Tete Jaune, rises the multicolored ridge of Mica

Mountain in the Cariboos. We are soon in Robson’s shadow and the top is

no longer in sight. Turning a corner we come out on the shore of Kinney

Lake, with the slopes of Little Grizzly and the pinnacle of Whitehorn

far above. Just now there is not a cloud to relieve the deep blue of the

sky, nor a ripple on the lake to disturb the images of tall trees and

soaring peaks. Some day there will be a hotel here and perhaps a

funicular; how much the worse!

Rounding the northern

shore of the lake, through the trees along the water’s edge, we cross

the expansive delta of glacial silt at its western end and take up the

trail again in the Valley of a Thousand Falls. There is a beautiful

glacier and a rock spire at the valley head, and if not quite a thousand

falls come streaming down from the cliffs on either side, the number is

at all events most satisfactory and surpassed only by the beauty of

their unbroken height. We cross through rushing streams, and slowly

climb up the thousand feet or more of zigzag trail, cleverly engineered

with wooden trestles, to the upper levels where the roar of Emperor

Falls is heard—dissonant to our vocal efforts in urging the horses

along.

Across the deep

valley-trench, Whitehorn is magnificent with its icy arete and hanging

glaciers, above a black precipice streaked with threadlike, silvery

waterfalls. Beyond the misty rainbows formed in the cauldron of Emperor

Falls, above tier on tier of horizontal strata and cliff-belts, rises

Mount Robson, steep and snowless, into an enormous wedge. Skirting a

burned-over, level area, and emerging from the woods, we reach the

marshy flats at the western end of Berg Lake, with distant views to

Robson Pass. The north side of Robson is sheer, but snow again appears.

The little basin at the foot of the snowy Helmet gives rise to the five

thousand feet of icefall known as the Blue, or Tumbling Glacier. There

are few places in the world where lake scenery can equal this prospect;

as we ride along, bits of the ice-front break off with a crash and the

fragments add to the number of floating bergs already sparkling in the

dark-blue water.

Just east of Tumbling

Glacier is the rocky promontory of Rearguard, with the tongue of the

Robson Glacier protruding beyond. The eastern end of the lake, Robson

Pass, is the end of our day’s ride. Stiff and tired, we slip down from

our sweating ponies, fatigue somewhat lessened by thoughts of a square

meal soon to be ours. The outfit was very sporty and had packed along a

portable stove, on which bear steak and potatoes were soon sizzling and

sending up delectable odours that distracted one’s attention from the

business of putting up tents. It was bitterly cold when the sun went

down, but we moved close to the fire, while Bert regaled us with tales

of sheep-hunting in the north country.

When I crawled out of

my blankets in the morning there was a film of ice on the nearby brook.

The northern face of Robson was clear and tinged with a rosy pink; and

promising noises from the cook-fly suggested a successful day ahead.

Breakfast over, we set out to explore the lower reaches of Robson

Glacier. Clambering over the morainal debris and up the tongue to the

glacial surface, we made our way over the parallel ridges of ice which

run in the longitudinal direction of the glacier. The tongue splits on

Robson Pass, a Pacific-Arctic watershed, some of the water flowing to

Berg Lake and reaching the Fraser, while another brook runs northward to

Lake Adolphus and Smoky River—a Mackenzie headwater. The glacier

originates in the high saddle and extensive neve fields between Robson

and Mount Resplendent, an extensive area of serac and crevasse running

eastward to the base of a curious buttress, resembling a candle-snuffer

and known as the Extinguisher, whence the level and unbroken glacier

runs northward for more than three miles to the pass. To the west, just

seen along the cliffs of Rearguard, Whitehorn lifts to a needle-point;

northward, the view is closed by Mount Mumm and peaks near Moose Pass

that border the valley of the Smoky.

During the afternoon we

sauntered over to Lake Adolphus and took a nap on the mossy banks. There

were superb views of the dazzling cone of Resplendent, and the glacier;

but Robson itself was hidden by the cliffs of Rearguard. Day ended in

glorious sunset, with afterglow on the snowy peaks. Even the cook could

not draw us into the tent until the last bit of gold and purple

colouring had merged into the green and dull grey of nightfall.

We made an early start

on the down-trail next morning and were back at the corral in the Grand

Forks by eleven o’clock. I spent a couple of hours fishing in the Fraser

and landed several small trout for lunch, rather opportune, for by this

time there was not much left of the bear steaks. It was the off day for

train service, so we decided on a hunting trip in the cabins at the

mouth of Grand Forks, and successfully bagged a choice assortment of

pack-rats that had grown sleek and fat from their forays on our

provisions. On the day following, we packed several fifty-pound sacks of

potatoes from the homestead’s garden to the railroad, and had still

energy enough to ride horses over to the old freight-road where we shot

three coyote that we had noticed in the edge of the grass. It was a tame

sport, but the fur was in good condition and the hides were soon tacked

up beside the bearskin.

In the evening we rode

bareback for a little way along the Fraser trail, driving the other

horses ahead toward Jasper.

It was not for a number

of years—the Great War had come and gone—that we could come back again

to Robson; not until the summer of 1924. In that season we were

completing our exploration of the Continental Divide, northward from

Lake Louise; we had been to Athabaska Pass and to the peaks of Tonquin

and on to Yellowhead. It was a July day, the 17th and cloudy to be

exact, when Conrad Kain, Alfred Ostheimer, and I unloaded our packs

before a crowd of curious tourists at Robson Station.

This time we had come

to climb; there would be more of hard work and less of sentiment than on

my first visit. But how changed things were! Cabins had sprung up like

mushrooms; there was a broad trail, almost a road, leading to a

well-engineered bridge spanning the Fraser canyon; permanent camps on

the summit of Robson Pass made it unnecessary to use horses or even

carry provisions. It was getting altogether too civilized! We put our

packs on our backs and started off, arriving in due course at Kinney

Lake. There we met the Oberland guides employed by the Canadian

National, Hans Kohler and Alfred Streich. They had been of the party

that came looking for us on Mount Hooker, and were now making themselves

acquainted with the Robson district prior to the camp of the Alpine Club

of Canada.

We had a pleasant walk

together, next morning, when we all went up to the cabins at Robson

Pass. We had not yet seen the top of Mount Robson, weather seemed to be

getting worse instead of better, and we were quite ready to believe the

Indians’ statement that it was, after all, rarely beheld by human eyes.

Fog hung in the valley, blowing in from the Fraser; then, in a change of

wind, coming back again from the Smoky. The mountain rises so much above

its immediate surroundings—scarcely a peak nearby approaches within two

thousand feet of its elevation—that, by its very isolation, it becomes a

storm centre. I thought longingly of the cloudless September days in

another year.

Enforced inactivity was

making us jumpy; so, on July 20th, although it was cloudy and a high

wind blowing, we all decided that something must be done. It occurred to

us to try Resplendent (11,240 feet), and go up as far as we could. So we

started out at halfpast six, and made our way to the glacier, wandering

up to the seracs and through a portion of them, killing time in the hope

that the wind would die down. It seemed amusing to try the rocks of the

north arete, the crest of which had been but twice followed throughout.

We roped below a little schrund, as well-guided a party as has ever

tackled a Canadian mountain. Ostheimer, with Kohler and Streich, made

one rope; while Conrad and I followed behind, showing wisdom therein, as

we could use them for a wind-break while they cut the steps. Streich had

quite a job of it; it was terribly cold, and the slopes below the rocks

were steep and hard. However, in an hour we were in the lee of a rocky

pinnacle and enjoying a second breakfast of bread and sardines. Conrad

and I then went ahead and found some quite delightful climbing in a

short stretch of chimneys and slanting slabs, where handholds were few

and body-friction alone kept one from swinging sideways on the rope. At

one o’clock we were on the upper snow-level below the peak; everything

was enveloped in swirls of mist, but the wind had lessened in force and

we could occasionally see for a short distance ahead. Resplendent is not

an easy mountain on which to lose the way, and though there was no view

to be had, Conrad led us through the fog to the steep-corniced summit in

another ninety minutes. There was still enough of a gale so that the

last portion had to be done carefully; Streich cut up to the cornice,

while the rest of us crouched down in the driving snow and anchored.

Each of us had a look over the edge, and then we beat a retreat to the

western snow-col at the head of Robson Glacier.

The fog-level had risen

to 10,000 feet, and under the edge of its grey blanket we looked far out

across the sunlit Fraser Valley to the borders of the Cariboos and peaks

beyond. Still no sign of a real break in the weather. As we descended

with long glissades into the main basin, the Bess Group was visible in

the north. There was just one momentary glimpse of Robson’s peak, rising

like a sword-point, vanishing again in the veil of billowing cloud. We

were back in camp, with good appetites, just twelve hours after our

start, feeling that we had accomplished something even under unfavorable

conditions.

Camp was being put up

for the annual activities of the Alpine Club of Canada, and the first

hikers arrived next afternoon. On the 22d, although the clouds hung low,

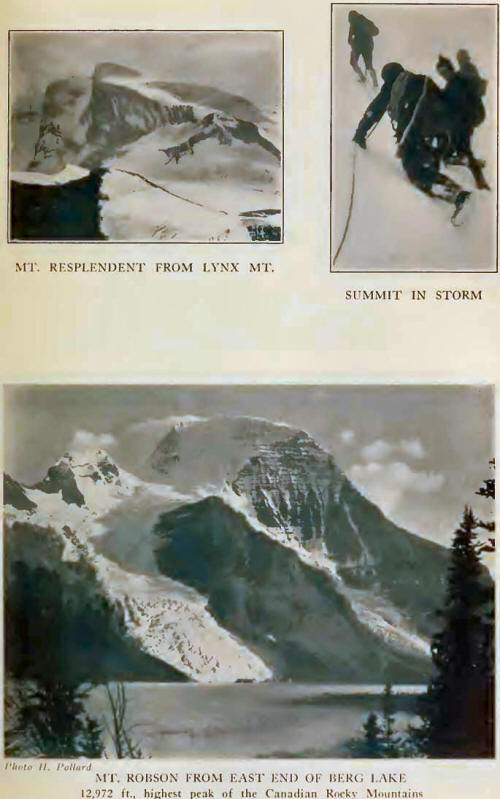

a large party on three ropes ascended Lynx Mountain (10,471 feet), an

attractive peak of the Robson cirque, commanding a widespread view of

the Robson and Coleman Glaciers and of Resplendent Valley. One ascends

snow-slopes, with a few steps to be cut, nearly to the southwestern

saddle whence a broad highway of rising shale leads to the summit. It

took six hours to reach the highest point, and but half that time for

returning, with many a boisterous glissade in the softening snow

carrying us almost to the glacier. Resplendent and Robson appeared

several times; never quite clear, but moist and shadowy in the mist.

Down Resplendent Valley we could see the slender needle known as the

“Finger of Kain,” and far to the south, momentarily of course, we

thought we could discern the jagged outlines of the Rampart Group.

Professor Coleman may

be considered the first to approach Mount Robson with the idea of

climbing it. As early as 1907, he and his companions had come over the

Saskatchewan and Athabaska trails from Laggan, and had reached the head

of Grand Forks Valley. They returned in the year following, going in

from Edmonton and gaining Robson Pass by way of Moose River and the

Smoky. After several attempts in bad weather, a final climb from the

glacier broke down at 11,000 feet.

In August, 1909, Rev.

G. B. Kinney and Donald Phillips attained the summit crest by way of the

northwest arete and western face. It was a fine, sporting effort and

deserves the credit of a first-ascent. Later in the summer a party of

distinguished British mountaineers—Messrs. Amery, Hastings and Mumm,

under the guidance of Moritz Inderbinen—had a further try at the eastern

face, but desisted after a narrow escape from an avalanche. The very

highest point was not attained until A. H. MacCarthy and W. W. Foster,

with Conrad Kain, reached it during the summer of 1913. Their route was

also by the dangerous eastern slope, but descent was made in a

southwesterly direction, with a night out, to Kinney Lake.

Writing for the Alpine

Journal, Conrad said of the southwestern ridge, “There is no doubt that

this ridge will be the future route to ascend to the summit of Mt.

Robson. But the climb cannot be done from Lake Kinney in one day. It

will be necessary to build a hut at the head of the Lake Kinney Valley.

The snow conditions on the highest peaks in the Canadian Rockies can

never be compared with those in the Alps, as there are more avalanches

in the Rockies on account of the dryness of the atmosphere, which leaves

the snow powdery and unpacked. And so I may say that Mt. Robson will

always be a risky climb, even on the easiest side, on account of

avalanches.”

In an article for the

Canadian Alpine Journal Conrad was no less emphatic, writing, “In all my

mountaineering in various countries, I have climbed only a few mountains

that were hemmed in with more difficulties. Mt. Robson is one of the

most dangerous expeditions I have made. The dangers consist in snow and

ice, stone avalanches, and treacherous weather.” During the ten years

since, Conrad no doubt modified this opinion of the mountain; but his

view in regard to the length of the climb was unchanged. He had so

carefully prospected the southwestern slopes of the mountain that the

real climbing difficulties were reduced to a minimum; but the danger

from falling ice could never be ignored. And so, although we had come to

the very foot of the all-highest, I had very little idea of doing more

than look up at it from lesser height. But the wretched weather had most

of the time effectually prevented even that much. Under the direction of

Phillips, a high camp (at about 6500 feet) had been placed near the last

trees in the gully above Kinney Lake; we had seen the white speck of a

tent, high on the green point, when we had come by the lake a number of

days before. We were rather pleased to be chosen to make an attempt with

the first official party from the main camp; as a matter of fact, our

vacation time was drawing near a close and the trial must be made now or

postponed for a long while.

And so, on July 23d,

with Messrs. Geddes, Moffat, and Pollard, Ostheimer and I—all members of

the Alpine Club of Canada—packed down to Kinney Lake. Conrad, of course,

led the way, adding considerably to our remarks about the unpromising

weather. As this would prevent serious climbing on the morrow we decided

to spend the night at the lake rather than go up to the higher level.

Mount Robson may be

considered as a gigantic wedge, rising—although structurally the lowest

point of a syncline—in buttressed heights to the summit icecap,

ten-thousand feet above the Grand Forks Valley. On its northern slopes,

exposed for only seven thousand feet, it presents a spectacle of snow

and ice; but the western and southern slopes, above timber-line, are

comparatively bare and rocky. It was this southern aspect that we had

beheld from the mountains of the Whirlpool, during our journey to

Athabaska Pass, when we marveled at the lonely isolation of the great

peak. From that point of view, the precipitous southeastern shoulder had

been so foreshortened as to be almost indistinguishable; but now, from

the shore of Kinney Lake, the lower cliffs and couloirs, with their

lines of horizontal strata, attracted our attention.

Next day it took five

hours to mount the steep trail through the woods to the climbing-camp.

Conrad had the heaviest pack of all—only slightly smaller than

himself—and was forced to “build a fence” of willow-twigs in order to

accommodate a pail and several loaves of bread on top. The afternoon was

spent in camp-work: chopping wood, carrying water, and in constructing a

well in the nearby gully.

Above the cliffs, a

little to the north of our tents, we could see rolling clouds which hid

the crest of Robson, but which lifted enough to show us the green seracs

of a lower icefall, from which two crashing avalanches came down just

before we started supper. Sitting on the limb of an ancient,

storm-gnarled tree, one felt that it would be quite possible to throw a

stone into the grey waters of Kinney Lake, three thousand feet below.

The lake was now in shadow, but the sun, breaking through the upper

levels, flooded Whitehorn with a luminous red-gold light. To the

southwest we could see across the bordering hills of Fraser River,

almost to the head of Canoe and North Thompson Rivers, and beyond to the

Cariboos, whose winding central glaciers were steeped in lavender, and

heliotrope—last pale colours of evening.

During the night the

clouds rolled back, and we started out at four o’clock on the finest of

clear mornings. In two hours we had climbed over long slopes of shale

and scree to the limits of vegetation, in the top of a small cirque near

the lower icefalls. These ice-falls, two in number and separated by a

narrow partition of cliff, owe their formation to a reconsolidation in

the avalanche ice that breaks off from the summit cap. Walled in on one

side by the southeastern shoulder it is forced, for the most part, into

the couloirs bounding the head of Kinney Lake Valley.

Early in the morning,

it was quite safe to cross close below these falls; we were quickly

through the short distance, floored with shattered blocks, without a

sign of anything giving way above. Then up and up the crest of a long,

rocky ridge, where the sun met us, to a flat ledge with a trickle of

water that met the requirements of a breakfasting place. On such a

level, Conrad told us, a hut should be constructed. It would necessitate

the carrying up of fuel, since timber-line is more than a thousand feet

below, but it would immensely facilitate the ascent.

We sat there, eating

bread and jam, a little below the first snow, and looked across to the

shoulder. Above the icefalls, under which we had recently crossed, is a

level of hardened snow swept by tracks of immense avalanches that had

come from the great furrowed icecap that sparkled above us. The cap

itself, from the western crest of the mountain to the top of the

southeastern shoulder is guarded by a veritable barrier of ice, some

hundred feet high. This is the real danger of the southwestern route:

one must work up through this upper fall, not often feasible, or

traverse under it, or a portion of it, toward the western arete.

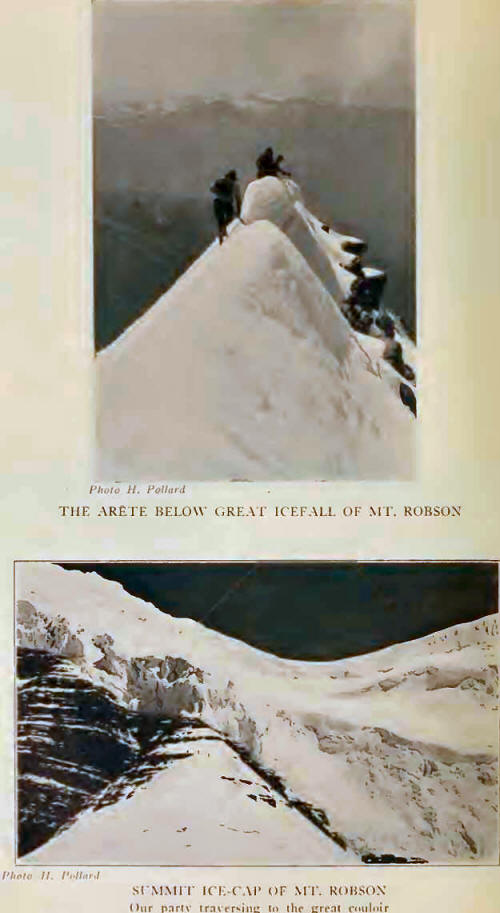

We were soon on the

snow; Conrad, Ostheimer and I on one rope, striking up a sharp

snow-crest that connects the rock ridge from the southwest with the base

of the ice-cap. We stopped to reconnoitre, while the other rope came up.

In the ice-cliff there was a choice between a frozen chimney, nearby,

blue and steep, which Conrad pronounced hazardous for the leading man,

and a lateral traverse on horizontal, snow-covered ledges, below the

seracs, to a break that seemed to afford access to higher slopes. The

traverse seemed the only course; but it looked nasty. It meant an

exposed crossing through the head of the great southwest couloir, so

conspicuous from the Grand Forks Valley. It was past the noon hour, the

ice was in the full light of a hot sun for the first time in a

fortnight; and the summit of the mountain, although less than two

thousand feet above us, showed us plainly enough that to go on meant a

night bivouac. Not very much more than two weeks before we had had two

long nights of shivering in the caves of Mount Hooker, and Ostheimer and

I were not keen for an immediate repetition of that mode of existence.

Just then there was an

ominous cracking, and Conrad shouted: “It’s coming down,” and we all

ducked under the nearest ledge. Fortunately only a few small cakes fell,

and these not near us. Still it does not take a very big piece to put

one hors de combat, and the business might not yet be done with. I made

up my mind that the amateurs on our rope must turn back. Everyone has

his own standard about what is to be done under such circumstances—mine

is that there is plenty of good mountaineering to be done without

knowingly placing oneself in an exposed position, requiring time for its

passage, where ice or rock may come down. I sometimes subject this to a

very liberal interpretation; but on this day, toward the end of a long

and successful season, I was not willing to take a chance on the good

behaviour of those ice-pinnacles.

The others felt

differently about it and inclined to go on. Conrad said, “Gentlemen, it

is risky. I am willing to go on if you wish.” So we decided that Conrad

should rope with them and continue, while Ostheimer and I on the rope

remaining should descend the ridge below, and continue to the high camp.

So we parted, wishing each other the best of luck.

The four were

immediately lost to sight behind a hummock of snow, while we descended

in the steps cut on the way up. We were near the level of Whitehorn,

with a widespread view across the Fraser Valley. It seemed to us worth

while to ascend the little rock-point which forms the very apex of a

buttress just south of the main couloir. From near Kinney Lake it seems

to rise as a sharp spire; but from below one does not see the snow that

extends behind and toward the ice-cap. We built a little cairn, and sat

down to watch the climber’s progress. All at once there was a grinding

crash in the direction of the couloir, and some large blocks of ice came

tumbing down. The men were still out of sight, but that shower of pieces

must have been uncommonly close to them. They were untouched, however,

and a little later we saw them gain the icecap through the break in the

seracs. Still later, as we descended, we saw them high up on the snow,

half hidden at times by veils of mist.

We had come down nearly

to the lower icefalls; we stopped to finish off some sardines and

coffee, seating ourselves on a broad ledge that seemed almost to

overhang Kinney Lake. Then something made us turn our gaze to the lower

ice. There was not a sound, but as we looked the entire front of

pinnacles began to move. Slowly the green wall tottered and sank,

splintering laterally and sweeping the path through which we had come in

the early morning. Then came the crashes. We sat as if petrified until

the last echoes died away. Conrad heard the noise, on top of Mount

Robson. He told me, afterward, that they spent the night near where we

had been sitting and thought that the avalanche had caught us. But no

such misfortune overtook us, and before dark we were in the blankets

beside the campfire.

Conrad and his

successful party came in at four o’clock next morning, all rather

tired—a night on the rocks is never restful. I got up, did what I could

to help get breakfast ready, and then packed down-trail to Kinney Lake,

eventually making Robson Pass in time for a belated lunch. The last pull

was a hard one. And so, after more than a thousand miles of trail-riding

through the Canadian Alps, with success on many high peaks, in more than

one long season, I have not conquered Robson—yet.

It is not fair to the

mountain to say that conditions are always such as have been described.

Later on, within only a couple of weeks, in 1924, a total of twenty

people had reached the summit without mishap. Perhaps after a few days

of sunlight the ice conditions were better. But to my mind there is

always a potential menace in those westerly-exposed seracs. If enough

parties try it, there will at some time be an accident from avalanche. I

have not yet forgotten whit Conrad wrote after the first-ascent, in

1913, “I do not know whether my Herren contemplated with a keen alpine

eye the dangers to which we were exposed.”

Mountaineering includes

a philosophy too optimistic for one ever to dwell on defeat; there is

always happiness in having tried with good comrades. Perhaps it were

best that I should never attain that height; I might think the less of

it. For, to me at least, it would be nothing short of sacrilege to stand

on the very summit of the majestic mountain that, when little more than

a boy, I went hunting for—and found—in the pale splendour of northern

moonlight.

7I have at least made

climbing contact with the first three of the 12,000 ft. peaks of the

Rockies of Canada. I wonder if some energetic climber will ever have all

four peaks—Robson, Columbia, North Twin, Clemenceau—on his list? |