|

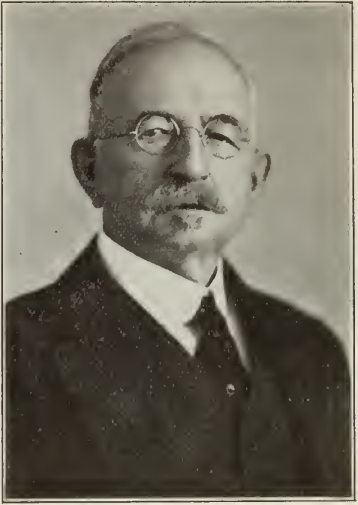

Canada’s most distinguished citizen, Lord

Shaughnessy, of Montreal, Canada, and of Ashford

County, Limerick, Ireland, died at his home in

Montreal, on Monday, December tenth, after an

illness of only twenty-four hours, leaving a record

of achievement behind him that has _ few _ parallels

in industrial history. His fine courage,

imagination, keen discernment and honourable

purpose, blended with remarkable ability, made him

great in purpose and successful in achievement.

No man ever had a higher conception of the

responsibilities of his position than Lord

Shaughnessy and few men ever discharged such great

responsibilities with so little friction. To grasp

the lever of a thousand phases of work with firmness

and confidence, to guide the destinies of the

greatest transportation system in the world,

required long, practical and thorough experience,

executive ability of a very high order,

discrimination and tact in selecting and dealing

with men.

That Lord Shaughnessy possessed these qualities no

one who knew him will dispute. A tireless worker, he

was throughout his life a man of indomitable energy,

endowed with strong commonsense and natural

faculties of a very high order, chief among these a

prodigious memory, responsive to the needs of the

moment — a surprise and sometimes a consternation to

those who witnessed its operation.

In 1882 Thomas Shaughnessy was selected by President

Van Horne for the position of general purchasing

agent. He was then under thirty years of age. In his

thirty-first year he was appointed to the position

of assistant general manager of the road, which he

held until 1889, being then appointed assistant to

the president. So valuable did he make himself in

that capacity that in June 1891 he was elected

director of the company and made vice-president.

Finally, on June 12th, 1898, when Sir William Van

Horne retired, Mr. Shaughnessy became president of

the Canadian Pacific Railway, and two years later

became also chairman of the board of directors,

which latter office he held to the time of his

death, being succeeded in the presidency on October

10th, 1918, by President E. W. Beatty.

In addition he was a director of a number of other

companies including the Bank of Montreal and the

Royal Trust Company.

For his services to Canada and the Empire, he

received the honour of knighthood (Knight Bachelor)

from King Edward in 1901.

In 1907 Sir Thomas Shaughnessy was accorded the

further distinction of Knight Commander of the Royal

Victorian Order.

Finally, on New Year’s Day, 1916, came the crowning

honour of his life, when he was elevated to the

peerage as a Baron of the United Kingdom by King

George. He chose the title of Lord Shaughnessy, of

Montreal, Canada, and Ashford County, Limerick,

Ireland, and took his seat in the House of Lords on

November 23rd, 1916.

He became a member of the Order of the Sacred

Treasure of Japan in 1901, and a Knight of Grace of

St. John of Jerusalem in 1910.

Lord Shaughnessy was one of the outstanding figures

in the world war. His advice was frequently asked

and followed by the Canadian and Imperial

governments. Upon the outbreak of hostilities he

placed the whole resources of the Canadian people,

ships and shops, at the disposal of the Allies,

while he himself threw wholeheartedly into the work

of recruiting in Montreal. His two sons, his heir

and his second boy, A. T. Shaughnessy, went to the

front and the latter was killed in France.

Lord Shaughnessy lived a quiet and unobstructive

life in his handsome residence on Dorchester Street

West. There he sometimes handled the cue on his well

appointed billiard table and relaxed so far as to

take a hand at bridge. He found in reading his only

other recreation. The few holidays he took he loved

to spend at “Fort Tipperary”, his beautiful summer

home at St. Andrew’s-by-the-Sea, N.B.

Lord Shaughnessy, K.C.V.O., Hon.M.E.I.C..

SHAUGHNESSY, THOMAS GEORGE, 1st Baron SHAUGHNESSY,

railway official; b. 6 Oct. 1853 in Milwaukee, Wis.,

son of Thomas Shaughnessy, a policeman, and Mary

Kennedy; m. 12 Jan. 1880 Elizabeth Bridget Nagle (d.

1937), and they had two sons and three daughters; d.

10 Dec. 1923 in Montreal.

Thomas G. Shaughnessy, the son of Irish Catholic

immigrants, was educated in public schools and at

the Jesuits’ St Aloysius Academy in Milwaukee. He

also studied for several months at the Spencerian

Business College in that city before entering the

service of the Milwaukee and St Paul Railroad at age

16. He served first as a clerk in the purchasing

department and then as a bookkeeper in the supply

division. In 1874 the railroad extended its service

to Chicago and was renamed the Chicago, Milwaukee

and St Paul, but popularly it was known simply as

the Milwaukee Road.

While employed in relatively low-level jobs,

Shaughnessy studied law privately for some time. In

1875 he was the successful candidate in a municipal

by-election in Milwaukee’s poor and predominantly

Irish Catholic Third Ward. He was re-elected several

times, serving continuously on the municipal council

from 1875 until 1882 and briefly, in 1882, as its

president. In 1875 he was made adjutant of the 1st

Regiment of the Wisconsin state militia. The

following year he sought, unsuccessfully,

appointment as clerk of the circuit court.

In 1880 William Cornelius Van Horne* became the

general superintendent of the Milwaukee Road and he

was soon favourably impressed by Shaughnessy’s

meticulous but, until then, unspectacular work in

the stores department. Van Horne promoted

Shaughnessy to the position of purchasing agent.

Theft, damage, and the unexplained disappearance of

goods, as well as collusion between suppliers and

purchasers, were perennial problems for railroads.

Shaughnessy and two others were chosen by Van Horne

in October 1880 to examine and report on the

administrative, security, and accounting procedures

in the stores departments of other large railroads.

Their report recommended numerous changes, which

Shaughnessy, who was appointed storekeeper

responsible for all major construction and operating

materials and supplies on 1 Jan. 1881, then

implemented on the Milwaukee Road.

Van Horne left the Milwaukee Road to become general

manager of the fledgling Canadian Pacific Railway on

2 Jan. 1882. He offered Shaughnessy the position of

purchasing agent for the entire CPR system.

Shaughnessy declined, but when Van Horne returned

for a visit in the fall of 1882 he accepted,

allegedly over a glass of Milwaukee beer. He began

work with the CPR in Montreal that November. The CPR

was then in serious financial difficulty. That

situation got progressively worse as construction

costs mounted and fund-raising efforts by syndicate

members, among them George Stephen, James Jerome

Hill*, and Donald Alexander Smith*, faltered.

One of Shaughnessy’s greatest accomplishments was to

reduce costs as much as possible. He introduced a

tight system of controls and accounting procedures

in the ordering and allocation of supplies and he

scrutinized all expenditures. Many materials,

particularly those needed by construction crews, had

to be requested weeks and often months in advance.

The company could save substantial sums if materials

were ordered to arrive only at the last possible

moment and then only in the exact amounts needed.

Unused or unneeded supplies were often subject to

deterioration and theft while in storage.

Shaughnessy had an essentially pessimistic view of

human nature, perhaps instilled in him by his

father, who had been a policeman and sometime

detective in an impoverished district of Milwaukee.

While he was active in local politics Shaughnessy

himself had seen much evidence of corruption and

waste. He was convinced that, given the opportunity,

suppliers, contractors, carriers, workers, and

anyone else would cheat the company. Constant

vigilance was essential. Everything had to be done

in accordance with the many rules and regulations he

introduced. He delighted in tracing even minor

transgressions and then publicly humiliating the

perpetrators, usually in writing to ensure that the

information became a part of the permanent record.

Even the company’s most trusted contractors and

senior officials were exposed to his wrath if, in

their efforts to get necessary work done on time,

they paid prices higher than was deemed appropriate

or if they failed in any other way to follow his

system.

Shaughnessy was a perfectionist. He had a particular

compulsion for cleanliness, washing his hands many

times a day. Whereas Van Horne ordered mountains

moved if they got in the way of his construction

program, Shaughnessy was more likely to berate

employees about a speck on the dining car cutlery,

imperfectly washed passenger cars, a spelling error

on a CPR hotel menu, and, of course, even minute

irregularities in any invoice. During the difficult

period of construction from 1882 to 1885, he and his

staff were exceptionally meticulous, some thought

paranoid, when reviewing bills in order to postpone

payments as long as possible. They looked for any

discrepancy in price, quantity, or quality of

material delivered or work done, no matter how

insignificant, which might justify delays or

substantial reductions in the company’s payments.

Shaughnessy resorted to and perfected many of the

tactics employed by companies teetering on the edge

of bankruptcy, paying only the minimum necessary to

avoid costly legal battles. In later years he took

particular pride in having delayed the payment of

millions of dollars and in slashing millions more

from bills with which he and his officials found

fault.

There were some obvious limits to these tactics. It

would not serve the CPR’s interest to push good

suppliers and contractors into bankruptcy or to

alienate them to the point where they would refuse

to have further dealings with the company.

Shaughnessy therefore collected detailed information

on their financial standing and obligations, paying

in cash only what they needed to remain in business.

For the balance, after all other stalling tactics

had been exhausted, he issued notes not immediately

negotiable and verbal promises of payment once

finances improved. The CPR’s interests, as

interpreted by him, always came first. He could be

exceptionally tough in difficult times, but was more

generous when the company’s position improved or

when alternative opportunities became available for

contractors and suppliers.

Shaughnessy’s skills earned him a reputation as a

stern, humourless, and rigid administrator; they

also won him a cherished promotion to assistant

general manager in 1885. This position allowed him

to impose his meticulous style of management on the

operations and expansion of the nearly completed but

still chaotic railway. He was not a man without

vision. Indeed, like Van Horne, he believed that the

CPR must become a multifaceted business empire. At

the same time his determination to make the entire

system run with clock-like precision provided a

perfect counterbalance to Van Horne’s visionary

enthusiasm.

Financial necessity, if not desperation, had made

Shaughnessy’s style of management essential in the

early years, but after 1888 the fortunes of the

company improved. Van Horne became president that

year and he and the directors named Shaughnessy

assistant president in September 1889. In 1891

Shaughnessy became a director and was elected

vice-president. Van Horne gradually assigned almost

all administrative responsibilities to Shaughnessy,

who succeeded him as president in 1899. The company

went on to achieve remarkable success, thanks in

part to good management but mainly to the rapid

settlement of the Canadian prairies [see Sir

Clifford Sifton] and the general improvement in the

economy. Prices of its shares, which hit a low of

$33 in the mid 1890s, rose to $283 in 1912, though

they would decline to $135 before Shaughnessy

resigned in 1918. The company operated 7,000 miles

of track when he became president in 1899; this

would increase to 12,993 miles in 1918. Vast sums

were spent in improving the track and rolling stock

and in numerous ancillary enterprises.

Shaughnessy was intimately involved in the

development of the Canadian Pacific’s steamship

service. During his presidency newer and larger

ships, tugs, barges, and ferries were acquired for

service on the Great Lakes, the inland waterways of

British Columbia, and the Pacific coast. A

profitable steamship service from Vancouver to the

Orient had been established in 1891 with three ships

forming the Empress Line. This service was

significantly improved during the Shaughnessy era by

the construction of new Empress ships, which were

then the fastest and best equipped on the Pacific.

In 1902 Shaughnessy decided the company should

establish its own Atlantic service. He took part in

the acquisition by the CPR of two Atlantic shipping

companies – the Beaver Line and the Allan Line [see

Andrew Allan*] in 1903 and 1909 respectively – and

in the addition of new ships, including some of the

most modern design. The Atlantic service earned only

modest profits, but it made the CPR one of the

world’s major shipowners.

The success of any large transportation system

depends on the passengers and freight carried and

CPR officials initiated or participated in numerous

projects designed to increase traffic. The most

important involved the settlement of prairie lands.

Vigorous attempts were made to attract settlers who

would purchase CPR land and generate freight.

Shaughnessy started major irrigation projects which

made almost 3,000,000 acres of dry land in southern

Alberta much more valuable. He also continued Van

Horne’s energetic efforts to augment passenger

traffic through the promotion of tourism. New CPR

hotels were built in Winnipeg, Calgary, and

Victoria. Those in Quebec City, Vancouver, Banff,

and Lake Louise were substantially enlarged and

smaller resort hotels in the Maritimes and several

chalets and camps in the mountains were added. All

had to meet Shaughnessy’s rigorous standards. The

Crow’s Nest Pass Railway, begun just before

Shaughnessy became president, captured the traffic

in coal, other minerals, and forest products of

southern British Columbia. Several mines and a large

smelter at Trail, B.C., had been acquired from

American promoters in 1898 and were merged in 1906

to form the CPR-controlled Consolidated Mining and

Smelting Company of Canada Limited. Coal was not

only an important freight commodity, it powered the

steam locomotives, so the company developed

important coalmining operations in southern British

Columbia. Under Shaughnessy’s watch the CPR became a

partner in several engineering, steel, rolling

stock, locomotive, and other manufacturing companies

whose products it needed.

For many years Shaughnessy represented the CPR on

the boards of major financial institutions with

which it had extensive dealings, including the Bank

of Montreal, the Royal Trust Company, the Accident

Insurance Company of North America, and the

Guarantee Company of North America. He received

numerous invitations from friends to invest

personally in a variety of ventures. A cautious man,

he placed his money in preferred CPR and CPR-related

securities. He did not amass the wealth of the great

American tycoons or even of some of his fellow CPR

directors, but he was almost certainly a millionaire

at the time of his death. He loved ceremony and

ostentation and was as meticulous about his clothes,

personal appearance, and private luxuries as he was

about the quality of the service provided by the

company. His two great loves were the CPR and his

family. He had little interest in philanthropy or

social causes.

Shaughnessy was a brilliant administrator who ran

one of Canada’s largest and most efficient

businesses in an effective, but cautious and not

very imaginative way. During his administration the

CPR, more than any other company, contributed to the

building of Canada as a nation. One of the most

important services the CPR provided was the

transportation of prairie wheat to export markets.

The main line made this possible, but it was the

massive construction of branch lines and the

significant reductions in freight rates during the

Shaughnessy years that allowed prairie homesteaders

far from the main line to establish successful

farms. The railway brought in the coal with which

the farmers heated their homes, but it also carried

manufactured products and supplies of all kinds,

dramatically expanding the economy of western Canada

and connecting it with that of central Canada. At

the same time, however, it became the primary focus

of regional discontent.

The CPR had always been viewed with considerable

suspicion in western Canada. It was alleged that the

rates charged were too high and that the services of

the company were not extended as quickly as they

should have been to newly settled areas. Many

believed both problems would be alleviated if the

CPR was exposed to effective competition. The

so-called monopoly clause in the railway’s charter

had kept rival American lines out of western Canada

until 1888, when political agitation in Manitoba

[see Thomas Greenway*] resulted in the cancellation

of that clause. Subsequently the CPR fought several

battles to exclude American railroads. As part of

its strategy it retreated from its attempts to

invade American territory. This change of policy

contributed to Van Horne’s resignation as president,

but it was offset by the success of the CPR in

beating back efforts by American lines to tap

western Canadian traffic. The construction of the

line through the Crowsnest Pass was particularly

important in securing the traffic of the southern

prairies and southern British Columbia.

In 1897, when the CPR was negotiating with the

federal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier* for a

subsidy to build the Crow’s Nest Pass Railway,

pressure from western farmers and their political

representatives had led the government to grant the

subsidy only if the railway significantly reduced

its rates. Under Shaughnessy’s administration, the

agitation for further rate reductions and more

branch lines both increased. In 1901, the Manitoba

government of Rodmond Palen Roblin* signed an

agreement with the promoters of the Canadian

Northern Railway, William Mackenzie and Donald

Mann*, to provide substantial guarantees for their

railway bonds in return for a significant reduction

in freight rates from Manitoba to the Lakehead. The

Regina Board of Trade later obtained an extension of

those lower rates to its city. To remain competitive

the CPR had to match the Canadian Northern’s rates.

In 1903 Charles Melville Hays* of the Grand Trunk

Railway, which was well established in Ontario and

Quebec, sought federal assistance to extend its

system to the Pacific. It too promised to compete

effectively with the CPR.

The federal and provincial governments believed that

wherever possible competition between railways

should be promoted as a means to ensure better and

cheaper service. Railways, however, often enjoyed

natural monopolies, particularly in sparsely settled

areas, so politicians moved to strengthen government

control. The authority of the small railway

committee of the Privy Council was greatly expanded

with the creation in 1903 of the Board of Railway

Commissioners [see Andrew George Blair*], which had

legal jurisdiction to settle many of the disputes

arising between rival railways and between railways

and the general public. It did not initially have

the power to set freight rates but, like the

Interstate Commerce Commission in the United States,

it had the power to order railways to reduce freight

rates which unfairly discriminated against some

customers. Many in western Canada were convinced

that the CPR’s ton-mile rates, which were higher

there than in central Canada, constituted such

discrimination. The CPR argued that the higher

western rates were justified by the cost of building

and operating the long and expensive line north of

Lake Superior. The Board of Railway Commissioners

eventually accepted this argument, enunciating it

explicitly in 1914.

Shaughnessy tried to deal with the threats of

competition prudently. He knew there was not

sufficient traffic to justify the construction of

two new transcontinental railways or the extension

of branch lines into the many sparsely settled parts

of the country. Under his administration the CPR had

constructed branches only where they could be

justified on sound economic grounds rather than on

grandiose promises of future development. When it

became clear in July 1903 that Ottawa would assist

the rival systems [see Blair], Shaughnessy proposed

a radical scheme under which the CPR would sell its

expensive but vital line north of Lake Superior to

the federal government, which could then double

track it and grant running rights to all competitive

railways. Shaughnessy was confident the CPR could

meet any threat except that posed by rivals enjoying

massive government assistance. Under his proposal

the subsidies would be sharply reduced and the CPR

would no longer be responsible for the operating

expenses of the difficult section, though it would

retain control over the entire system. Laurier was

wary of government ownership and feared that

Shaughnessy’s proposal would prevent competition.

After the Liberals won the election of 1904 the

construction of the two new transcontinentals

proceeded.

When war broke out in 1914 Shaughnessy gave his full

support to the war effort. He organized imperial

transport and assisted in the financing of the war

effort through loans to the government. Employees

were encouraged to enlist. Senior staff were lent to

the British and Canadian governments to purchase,

organize, and ship supplies overseas. Construction

workers were sent to rebuild damaged railways in

France and Belgium. The company’s largest and

fastest ships were requisitioned as transports and

auxiliary cruisers and the company’s machine shops

in Montreal and Winnipeg manufactured munitions and

military equipment. Shaughnessy suffered enormous

personal loss when one of his two sons, both of whom

served overseas, was killed in action in France.

Canada did not need, but it had obtained, three

transcontinental railways. All three adopted

aggressive competitive tactics. The CPR, which had

received federal cash and land subsidies, had a

decisive advantage over its rivals, which had

obtained only government guarantees for their bonds.

Both new transcontinental systems got into serious

financial difficulty during World War I. The CPR had

the necessary resources to take over parts or all of

the other systems, but such a solution was deemed

politically unacceptable by the Canadian government.

Instead, the federal government moved slowly toward

nationalizing them. The CPR’s directors, including

Shaughnessy, who had resigned as president in 1918

but would continue to serve as chairman of the board

until his death, found the notion of competition

with a government railway system abhorrent. A state

system would be vulnerable to political pressure to

offer unreasonably low rates and would then look to

the government to cover any deficits. In a desperate

effort to thwart such unfair competition,

Shaughnessy proposed in August 1921 the sale of the

assets of the CPR to the government in exchange for

a guaranteed return of interest and principal to the

holders of CPR stocks. CPR management – in

Shaughnessy’s opinion the best anywhere in the world

– would then sign a contract to manage the entire

system on behalf of the government. This proposal,

however, was also rejected by Ottawa. As a result,

the CPR was left to manage its operations in the

most efficient manner possible. Its profitability

was severely limited because it had to compete with

the Canadian National Railways (established in 1918

with the merger of the Canadian Northern, the

Canadian Government Railways, and other lines),

which could offer politically desirable but not

necessarily economically viable rail services. Only

extensive diversification and the earnings of

affiliated companies made it possible for the CPR to

retain its overall profitability in the later years

of Shaughnessy’s presidency.

Failing eyesight had led Shaughnessy to resign from

the presidency of the CPR. His frequent visits to

Britain and particularly his wartime work had

brought him into close contact with leading British

politicians, financiers, and businessmen who

recognized his administrative talent. They suggested

new areas of service to him after surgery resulted

in a partial restoration of his eyesight. He had a

long-standing interest in the affairs of his

ancestors’ homeland and became active after the war

in opposing the establishment of a republican form

of government in Ireland. There were rumours that he

might be named governor general of the Irish Free

State or be offered some other position in the

British government. No appointments was ever made,

however. He remained in Canada and continued to work

for the CPR until the time of his death, having

followed the advice he gave on his deathbed to his

successor, Edward Wentworth Beatty*, “Maintain the

property. It is a great Canadian property, and a

great Canadian enterprise.”

Thomas G. Shaughnessy had been made a knight

bachelor on 17 Sept. 1901, created a kcvo in 1907,

and elevated to the peerage of the United Kingdom as

Baron Shaughnessy on 1 Jan. 1916. He suffered a

massive heart attack on 9 Dec. 1923 and died the

following day. At the pinnacle of his career his

identity and that of the CPR seemed inseparable. His

achievement did not lie in the conception of grand

designs but in the management and execution of an

administrative system which carried the CPR to its

greatest business success as the country’s most

important and profitable multifaceted business

empire. He could not, however, ward off the

encroachments which left the CPR and the country

with serious railway problems.

Lord Shaughnessy,

who has died aged 81, was the rugged voice of

Canada in the Lords, where he took his seat

shortly before the Normandy landings, but waited

38 years before making his maiden speech.

Describing it as

more of a "spinster" effort, he rose as a

crossbencher to support a Bill to remove

Canada's constitutional document from the

Westminster Parliament to Ottawa.

Speaking partly

in French, he acknowledged that feelings of

alienation existed in both Quebec and Western

Canada, but emphasised that the Bill was "a

characteristically Canadian compromise" which

should not be amended.

"My Lords," he

boomed in his rich Canadian tones, "in political

terms, we are the masters of our fate and the

captains of our souls, and the resolution of our

differences must be made in Canada." Thereafter,

he remained a sedulous attender until he was

excluded by Tony Blair's reforms in 1999.

William Graham

Shaughnessy was the great-grandson of an

Irishman who emigrated from Co Limerick and

became a police detective in Milwaukee. His

grandfather became general purchasing agent and

later president of the trans-continental

Canadian Pacific Railway; in 1916 he was created

the 1st Baron Shaughnessy of Montreal and

Ashford, Co Limerick.

Young Bill

was born in Montreal on March 28 1922 and at 16

succeeded his father, a lawyer with the CPR,

while still at Bishop's College School in

Quebec. He went on to Bishop's University, then

left to be commissioned in the Canadian

Grenadier Guards.

Shaughnessy spent two years

stationed on the English South Coast, during

which he married Mary Whitley, an ATS officer,

in 1943, and took his seat the following year

under the benign eye of Viscount Bennett, the

former Canadian Conservative Prime Minister.

Six weeks later "Shag"

Shaughnessy, as he was known in his regiment,

landed on Juno Beach in July as part of 4th

Armoured Division. He bivouaced in a Sherman

tank for a couple of weeks before being thrown

into some of the toughest fighting, when the

division was sent to plug the gap between Caen

and Falaise. As he and his comrades moved into

the Rhineland, Shaughnessy was mentioned in

dispatches and became the last member of the

regiment to fire a shot in action, in May 1945.

Returning from the war,

Shaughnessy studied journalism at Columbia

University, New York, then joined the British

United Press news agency in Montreal, covering

general and sports news. After a time he moved

into the political arena, becoming executive

assistant to Douglas Abbott, the federal finance

minister in Ottawa, and helping the Liberals at

election time in the city of Westmount.

Commuting from Montreal to Ottawa

involved some strain, which was not eased when

he was involved in a run-in with the Montreal

police one night. He and his wife had an

argument with a taxi driver over a $1.55 fare

(about 11s 3d), which resulted in their being

driven to a police station, where Shaughnessy

spent the night before being fined $10.

Later, there were rumours that

they had been to a fancy dress party and that

the policemen they encountered was unconvinced

that the strong Irish features beneath the

Father Christmas outfit were those of a peer.

"If you're Lord Shaughnessy," the

officer is said to have commented, "I'm Santa

Claus." Despite appearances, however, this was

untrue, although Shaughnessy dropped a case for

wrongful arrest because of the publicity it was

attracting. Nevertheless, the incident is one of

the great urban myths of English Montreal.

Although the 1st Baron had been a

rich man, the Shaughnessy clan moved out of the

family house, a fine example of Scottish

baronial architecture in downtown Montreal which

is now the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Shaughnessy next went into the

pulp and paper business, owning a company called

W S Hodge, then moved to Calgary as

vice-president of Canada North West Energy, an

oil exploration company.

After a few years he was asked to

open a London office to supervise an offshore

drilling operation in Spain. But he retained

links with another oil exploration company in

the Caribbean and a firm of undertakers in

Toronto; he was also a member of the

Canada-United Kingdom Chamber of Commerce.

Shaughnessy was a member of the

Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments, but

did not speak often. Nevertheless, he would

occasionally rise, sometimes from what the

unwary assumed was a deep sleep, to remind the

House of Canada's contribution to Nato or to

defend General de Chastelain from suggestions

that he had no political nous.

When Lord Janner of Braunstone

stated that he had been picked on for being

Jewish as a boy at Bishop's College School

during the war, Shaughnessy was quick to deny

that there was any evidence of anti-Catholic or

anti-Jewish bias in his time there (shortly

before Janner).

Shaughnessy received a double

blow in rapid succession in 1999 when his wife

died and then he lost his seat in the ballot of

hereditary members permitted to remain in the

House. "Well, I must get on with the rest of my

life," he said afterwards.

Although he had sat as a

crossbencher in the House, Shaughnessy joined

the Association of Conservative Peers after

losing his seat, acknowledging Conservative

principles and becoming a regular attender at

its Thursday meetings.

Shaughnessy, who died on May 22,

is survived by two daughters and a son, Michael,

born in 1946, who succeeds as the 4th Baron;

another son predeceased him.

|