|

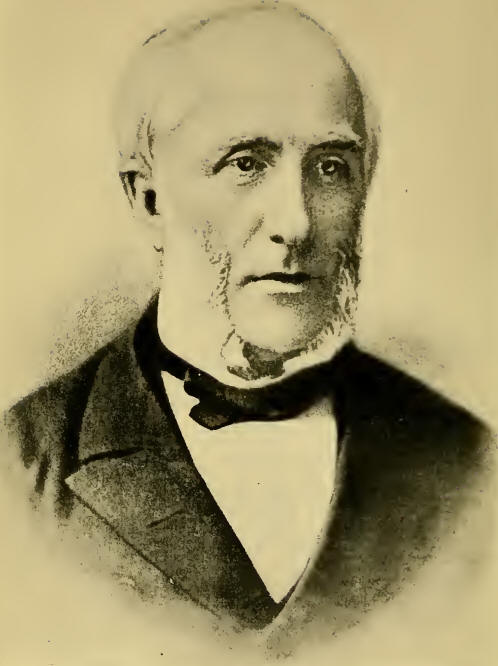

(1818-1880)

EARLY in 1864 when

party government in Canada had collapsed and leaders were casting about

for a solution, George Brown secured the appointment by the House of

Assembly of a committee of nineteen members to consider the difficulties

connected with the government of Canada. When the committee met

considerable time was consumed in banter and in debating whether their

meetings should be open or private. At last, when they had decided on

the latter course, Brown walked to the door, locked it and put the key

in his pocket. Then he said, to the astonishment of John A. Macdonald,

George E. Cartier and others, “Now, you must talk about this matter, as

you cannot leave this room without coming to me.”

The incident, which Brown related years afterward to a friend, is

illustrative of his own dominating, downright character. He was as

earnest as a crusader, as courageous as a knight at arms, and as

unyielding as an oak. For thirty years he was a towering figure in

Canadian life. He was a powerful and tireless campaigner, holding his

audiences far into the night with long speeches replete with

chastisement of his opponents. He was a fearless editor who filled the

columns of The Globe with high-tensioned opinions on every phase of

politics. He was a constructive statesman who was brave enough to forego

his most precious possession—party solidarity—and join a coalition

government to remove the first obstacle to Confederation.

George Brown and John A. Macdonald were political foes for more than

twenty years. Their lives paralleled and they constantly crossed swords.

Each was the idol of his party, though Brown’s unbending qualities

frequently caused trouble with men of his own side. Macdonald,—human,

winning and not less powerful, —was always in favor with his own party.

The two were forever in each other’s light and they were personal as

well as political enemies. Brown distrusted Macdonald for his sagacity

and perfection of statecraft. Macdonald disliked the serious, bold,

masterful Brown, whose editorial attacks were untempered and

unrelenting. Macdonald was social and convivial by nature. Brown was

stern and seriously attentive in his public duties. For years they were

not on speaking terms; then for public reasons they joined in the

coalition of 1864, yet a year later when Brown left the Cabinet their

intercourse entirely ceased. In 1867, Brown, addressing the Liberal

convention in Toronto when William McDougall and W. P. Howland were read

out of the party for remaining in the Macdonald Cabinet, declared his

feelings towards Sir John Macdonald by saying:

“If, sir, there is any large number of men in this assembly who will

record their votes this night in favor of the degradation of the public

men of that party (the Liberal) by joining a coalition, I neither want

to be a leader nor. a humble member of that party. If that is the reward

you intend to give us all for our services I scorn connection with you.

Go into the same government with Mr. John A. Macdonald (Cries of 46

‘Never’). Sir, I understood what degradation it was to be compelled to

adopt that step by the necessities of the case, by the feeling that the

interests of my country were at stake, which alone induced me ever to

put my foot into that government; and glad was I when I got out of it.”

These sentiments, making allowance for the exhilaration of a party

convention, reflect the sacrifice which Brown suffered for

Confederation. It is difficult in these days of temperate politics to

appreciate the degree of his sense of humiliation. Macdonald was his

chief adversary in life, the man whom tens of thousands of Canadians had

heard him denounce in his campaign utterances, and who was daily the

victim of his editorial lashings.

Yet on almost a day’s notice Brown, realizing the futility of further

fighting along party lines, joined his opponent and made Confederation a

possibility. Though Macdonald had many occasions to resent the attacks

of Brown and The Globe, he was generous enough in 1866 in a speech at

Hamilton to pay this tribute to Brown’s service:

“An allusion has been made to Mr. Brown, and it may perhaps be well for

me to say that, whatever may be the personal differences which may exist

between that gentleman and myself, I believe he is a sincere well-wisher

and friend of Confederation. I honestly and truly believe him to be so,

and it would be exceedingly wrong and dishonest in me from personal

motives to say anything to the contrary.”

On the other hand, Macdonald’s personal feelings towards Brown were

vigorously expressed in a letter to his mother in 1856, in which he

said:

“I am carrying on a war against that scoundrel Brown, and I will teach

him a lesson that he never learnt before. I shall prove him a most

dishonest, dishonorable fellow and, in doing so, I will duly pay him a

debt I owe him for abusing me for months together in his newspaper.”

Brown bore a relation of intimacy to Upper Canada similar to that of

Howe in Nova Scotia. He travelled it from end to end and pierced the

back settlements by horse and carriage long before the railways had laid

their network of steel. To the pioneers in the “Queen’s Bush” he carried

the message of political argument for which they hungered, and gladly

did they listen to his speeches until far beyond midnight. He moved

among the farmers, inspected their schools, visited their homes, and

talked sympathetically and knowingly of their crops. At night he would

address them in the largest hall that could be found, and frequently an

overflow meeting was necessary. Political beliefs were then held more

tenaciously than now, and the antiseptic effects of independence had not

made headway against the old “Grit” and “Tory” maladies. Many a meeting

was held in the hall above a driving shed attached to a tavern, and the

near presence of a bar did not lessen the enthusiasm of the occasion.

Candles were the illuminant, and their tiny flames did little to pierce

the gloom of the malodorous interiors.

Such heavy campaigning, combined with his editorial duties, would

overtax most men. George Brown was no weakling in any sense. He has been

described by a friend as a “steam engine in trousers,” and had he lived

in more recent times would no doubt be called “a human dynamo.” He

seemed never to stop working. His mind was ever on the alert, and his

body was able to keep pace with it. Living before the advent of

typewriters and the fashion of dictating, he laboriously wrote his

editorials by hand, using a pencil never more than two inches long. Mr.

J. Ross Robertson recalls the incident of the assassination of Lincoln

in 1865. He was on The Globe staff at the time, and on receiving the

despatch carried the news to Brown’s house, and waited while his chief

wrote an editorial on the subject, though it was then late at night.

Brown’s success and dominating place in the life of Upper Canada were

not the result of accident. His parentage and early training were the

natural preparation for such a life. He was born at Alloa, near

Edinburgh, on November 29, 1818, his father, Peter Brown, being a

respected citizen of the modern Athens, a friend of Scott and of other

worthies of that day. Dr. Gunn, head of the Academy of Edinburgh, which

George attended, spoke with insight at a public gathering when in

introducing the lad as he was about to declaim an exercise he said:

“This young gentleman is not only endowed with high enthusiasm, but he

possesses the faculty of creating enthusiasm in others.”

When George was twenty years old his father, having become heavily

involved financially, set out for America, bringing the youth with him.

Peter Brown founded The Albion, a paper for British-born residents of

the United States. In 1842 he founded The Weekly Chronicle, with himself

as editor and his son as business manager, and made it a paper for

Scottish-Americans. A year later George Brown visited Canada to seek

circulation for his paper, and the visit was the turning point in his

career. Tall, graceful, of good address, he was welcomed wherever he

went. After visiting Toronto he went to Kingston, where members of the

Baldwin-Lafontaine Government enlisted his interest in the fight for

responsible government, still far from won. George Brown persuaded his

father to move to Toronto, where The Chronicle was changed to The

Banner, making its first appearance August 18, 1843. The mission of The

Banner as an organ of the Free Church was soon found too limited, and

the Browns met the necessities of the case by founding The Globe, whose

first issue appeared March 5, 1844, it being the organ of the

Baldwin-Lafontaine Government and the champion of “Responsible

Government.”

No time was lost in declaring that “the battle which the Reformers of

Canada will fight is not the battle of the party but the battle of

constitutional right against the undue interference of executive power.”

Lord Metcalfe was quick to raise the loyalty cry, so often since used in

Canadian elections, and his party declared the contest to be between

loyalty on the one side and disaffection to Her Majesty’s Government on

the other. The Governor won in 1844, but the Reformers swept the country

in 1848, a result for which George Brown was largely responsible, and

the battle for responsible government was won.

Brown now required a fresh field for his endeavor, and in 1850 plunged

into an agitation for the secularization of the clergy reserves. The

Baldwin-Lafontaine Government retired in 1851 and its successor, the

Hincks-Morin Government, met with the opposition of Brown and The Globe.

About this time Brown became the recognized champion of Protestantism

because of his attack on the pronunciamento of Cardinal Wiseman, who had

been sent to England by the Pope. This ultra-Protestant view, for which

he has often been criticized on the broader ground of national

sentiment, alienated the Catholic vote in Haldimand, where Brown was

first a candidate for Parliament in 1851. His principal and successful

rival was William Lyon Mackenzie, then returned from his exile. JBrown

entered Parliament later in the year as member for the then backwoods

county of Kent, and at once took a commanding place. Clergy reserves

were secularized, and the seigniorial tenure was abolished a little

later, but Brown demanded representation by population and the abolition

of Separate Schools. His motion in 1858 disapproving of the selection of

Ottawa as the capital of Canada was carried, the Government resigned,

and Brown was called on to form a Cabinet. He chose his friend, A. A.

Dorion, as associate from Lower Canada, but the Governor-General

refusing a dissolution, the Premier and his Cabinet resigned after

holding office for two days. The former Ministers returned to office as

the Cartier-Macdonald Government, following what is known as the “Double

Shuffle.”

Such card game politics were but the beginning of the critical years

leading up to 1864. In November, 1859, the Reformers of Upper Canada, as

a great convention in Toronto, took an aggressive stand in denouncing

the union of 1841. They declared it had failed to realize the

expectations of its promoters, and favored a federation of the two

Canadas.

Brown, in his speech, said some of his friends throughout the country

were in favor of a federation of all the Provinces. “For himself, he

would not favor a federation so far extended. No, let there first be a

federation of the Canadas, and then bring in the other Provinces if they

found it advisable. Perhaps in saying this he might be looked upon as

behind the progress of the age. But he thought the great difficulty with

Canada was that she was too vast. Instead of stretching out, let them

trim their sails and scud along under close reefed topsails until they

got into smooth water.” The Reformers’ resolution was defeated in

Parliament at the next session, but it undoubtedly had an effect in

crystallizing public sentiment. Brown was defeated in his riding in

1861, and went abroad for his health, returning late in the following

year. The deadlock was now rapidly developing, and the country’s

business came to a standstill. To add to the embarrassment of the

situation, Britain was pressing Canada to take a greater share in her

own defence, for the vast American armies were on the eve of release

from the Civil War, with a bitter feeling against Canada for her alleged

sympathy with the South. In yet another way Canada's interests were

menaced by the impending abrogation of the Reciprocity Treaty which had

brought prosperity to the country.

Writing to his family on May 16, 1864, Brown sensed the crisis when he

said: “Things here are very unsatisfactory. No one sees his way out of

the mess —and there is no way but my way. representation by population.

There is great talk to-day of a coalition; and what do you think? Why,

that in order to make the coalition successful, the Imperial Government

are to offer me the governorship of one of the British Colonies! I have

been gravely asked to-day by several if it is true, and if I would

accept!! My reply was, I would rather be proprietor of The Globe

newspaper for a few years than to be governor-general of Canada, much

less a trumpery little province.”

On June 14 Brown, as chairman of the committee named to consider the

difficulties connected with the government of Canada, reported in favor

of “a federative system applied either to Canada alone or to the whole

of the British North American Provinces.” On the same day the Tache-Macdonald

Government was defeated and resigned.

The time had now come for action that would clear up the chaos once for

all. Coalition talk had been in the air for several weeks, and it is

somewhat uncertain who first gave utterance to it. The records show that

on the next day Brown spoke to two Conservative members, Alexander

Morris and John Henry Pope, and promised to co-operate with any

government that would settle the constitutional difficulty. A day later

John A. Macdonald and George Brown met in reconciliation. Macdonald

asked Brown if he had any objection to meet Galt and himself. Brown’s

reply was, “Certainly not,’:—the exact words have been carefully

preserved. The following day Macdonald and A. T. Galt called upon Brown

at the St. Louis Hotel in Quebec, and negotiations began which resulted

in the coalition being formed. Though the rival leaders were in amiable

converse, there was still a secret mistrust each of the other, as was

shown by the careful setting down of the conversation and the points

agreed upon. A farmer dealing with a lightning rod agent would not be

more careful. The first meeting failed of agreement. Later Cartier

joined the group and an agreement was reached in these terms:

“The Government are prepared to pledge themselves to bring in a measure

next session for the purpose of removing existing difficulties by

introducing the federal principle into Canada, coupled with such

provisions as will permit the Maritime Provinces and the Northwest

Territory to be incorporated into the same system of government and the

Government will seek, by sending representatives to the Lower Provinces

and to England, to secure the assent of those interested which are

beyond the control of our own legislation to such a measure as may

enable all British North America to be united under a general

legislature upon the federal principle.”

While Brown was ready to co-operate with Macdonald to secure

Confederation he was not ready to enter a Cabinet with him. Lord Monck,

the Governor-General, now took a hand by urging Brown to take office. In

his letter of June 21 Lord Monck said:

“I think the success or failure of the negotiations which have been

going on for some days with a view to forming a strong government on a

broad basis depends very much on your consenting to go into the Cabinet.

Under these circumstances I must again take the liberty of pressing upon

you, by this note, my opinion of the grave responsibility which you will

take upon yourself if you refuse to do so.”

Two days later Brown wrote to his. family that in consenting to enter

the Cabinet he was influenced by private letters from many quarters and

still more by the urgency of Lord Monck. Further, and finally, there was

the prospect that otherwise the whole effort for constitutional changes

would fail and the advantages gained by the negotiations be lost. “And

it was such a temptation,” he adds, “to have possibly the power of

settling the sectional troubles of Canada forever.” “The unanimity of

sentiment is without example in this country,” he goes on, and then

comes this introspective glance:

“And were it not that I know at their exact value the worth of newspaper

laudations, I might be puffed up a little in my own conceit. After the

explanations by ministers I had to make a speech, but was so excited and

nervous at the events of the last few days that I nearly broke down.”

Mr. Brown was not the only man who was excited. Sir Richard Cartwright

relates a comical incident of the day:

“On that memorable afternoon when Mr. Brown, not without emotion, made

his statement to a hushed and expectant House, and declared that he was

about to ally himself with Sir George Cartier and his friends for the

purpose of carrying out Confederation, I saw an excitable elderly little

French member rush across the floor, climb up on Mr. Brown, who, as you

remember, was of a stature approaching the gigantic, fling his arms

about his neck and hang several seconds there suspended, to the visible

consternation of Mr. Brown and to the infinite joy of all beholders,

pit, box and gallery included.”

Once the Canadian Parliament was committed to a settlement of the

constitutional question, events moved quickly. Mr. Brown joined his

colleagues in the visit to the Charlottetown Conference, spoke with them

afterwards in the Maritime Provinces, and took part in the Quebec

Conference in October when the basis of union was drafted. During this

conference some controversies arose and he was one of the majority who

favored a nominated Senate, thus differing from Mowat and McDougall. He

declared his belief that two elective chambers were incompatible with

the British parliamentary system, and that an elected upper chamber

might claim equal power with the lower, including power over money

bills. The delegates then visited Canada and explained the terms of the

proposed union.

Brown was now a thorough convert to the idea of the larger union and

expounded it with the same fervor that had lashed Upper Canada into

discontent over the union of 1841. Speaking at Halifax after the

Charlottetown Conference, he said:

“Our sole object in coming here is to say to you— 'We are about to amend

our constitution, and before finally doing so we invite you to enter

with us frankly and earnestly into an inquiry whether it would be or

would not be for the advantage of all the British American colonies to

be embraced in one political system. Let us look the whole question

steadily in the face—if we find it advantageous, let us act upon it, but

if not, let the whole thing drop.' That is the whole story of our being

here—that is the full scope and intention of our present visit.”

Mr. Brown also spoke at Montreal during the delegates5 tour, and at a

great banquet in Toronto he explained the scheme in detail. Upper Canada

was now agog with interest in the proposals and when the delegates

reached Toronto late at night a crowd of eight thousand met them at the

station.

Of the many worthy speeches delivered during the Confederation debate in

the winter of 1865, Mr. Brown’s stood out for its complete analysis and

well considered arguments. It may not have been the most eloquent

speech, but it presented the case for Confederation in an orderly and

convincing manner. Mr. Brown spoke for four and one-half hours.

“For myself,” he said, “I care not who gets the credit of this scheme—I

believe it contains the best features of all the suggestions that have

been made in the last ten years for the settlement of our troubles, and

the whole feeling in my mind now is one of joy and thankfulness that

there were found men of position and influence in Canada who at a moment

of serious crisis had nerve and patriotism enough to cast aside

political partisanship, to banish personal considerations and unite for

the accomplishment of a measure so fraught with advantage to their

common country.

“One hundred years have passed away,” he went on, “since the conquest of

Quebec, but here sit children of the victor and of the vanquished of

avowed hearty attachment to the British Crown—all earnestly deliberating

how we shall best extend the blessings of British institutions—how a

great people may be established on this continent in close and hearty

connection with Great Britain. Where in the page of history shall we

find a parallel to this? Will it not stand as an imperishable monument

to the generosity of British rule? Does it not lift us above the petty

politics of the past, and present to us high purpose and great interests

that may yet call forth all the intellectual ability and all the energy

and enterprise to be found among us?”

Mr. Brown gave seven strong reasons for supporting the union scheme: (1)

Because it will raise us from the attitude of a number of inconsiderable

colonies into a great and powerful people; (2) because it will throw

down the barriers of trade and give us the control of a market of four

millions of people; 58 (3) because it will make us the third maritime

power in the world; (4) because it will give a new start to immigration

into our country; (5) because it will enable us to meet without alarm

the abrogation of the American Reciprocity Treaty in case the United

States should decide upon its abolition; (6) because in the event of war

it will enable all the colonies to defend themselves better and give

more efficient aid to the Empire than they can do separately; and (7) it

will give us a seaboard at all seasons of the year.

Looking back, after fifty years, at Mr. Brown’s arguments and

expectations, it cannot be said that he overstated the case. His

conclusion was equally restrained and yet hopeful.

“The future destiny of this great Province,” he said, “may be affected

by the decision we are about to give to an extent which at this moment

we may be unable to estimate, but assuredly the welfare for many years

of four millions of people hangs on our decision. Shall we then rise to

the occasion? Shall we approach this discussion without partisanship and

free from every personal feeling but an earnest resolution to discharge

conscientiously the duty which an overruling Providence has placed upon

us? It may be that some among us will yet live to see the day when as a

result of this measure a great and powerful people may have grown up on

these lands—when the boundless forests all around us shall have given

way to smiling fields and thriving towns—and when one united government

under the British flag shall extend from shore to shore; but who would

desire to see that day if he could not recall with satisfaction the part

he took in this discussion?”

Brown’s connection with the coalition government was destined to be

short-lived. He seemed never to regard it in any other light. After his

return from the Quebec Conference, in a family letter he said: “At any

rate, come what may, I can now get out of the affair and out of public

life with honor, for I have had placed on record a scheme that would

bring to an end all the grievances of which Upper Canada has so long

complained.”

During the summer of 1865 he accompanied John A. Macdonald, Galt and

Cartier to England to confer with the Imperial Government regarding

federation, defence, reciprocity and the acquisition of the Northwest

Territories. In November of that year he resigned from the Cabinet. The

reason given was his difference with his colleagues regarding the form

of the possible renewal of reciprocity with the United States; he

favored a definite treaty as before, while they favored concurrent

legislation. It is altogether likely that this explanation was a mask

for his firmly held desire to make his exit from an unhappy environment.

On retiring he made it plain to Lord Monck that he would continue to

support Confederation until the new constitution became effective.

James Young in his “Public Men and Public Life in Canada” tells of a

meeting with Mr. Brown at Hamilton station just after his resignation.

He still showed signs of the mental and physical excitement through

which he had just passed. During the conversation Mr. Brown referred to

the differences over reciprocity, but said the relations between himself

and Macdonald had greatly changed since Brown had refused to consent to

his rival’s elevation to the Premiership. In short, Mr. Brown “had come

to the conclusion that for some time Attorney-General Macdonald had been

endeavoring to make his position in the Cabinet untenable unless with

humiliation and loss of popularity on his part.”

Having abandoned his temporary political allies —and sober historians of

both parties view the step as a mistake—Brown set himself to reuniting

his party. Oliver Mowat, who had gone into the Cabinet with him, was now

on the Bench, and he had been succeeded by W. P. Howland. William

McDougall, the other Reformer in the coalition, and Howland were pressed

by Macdonald to remain in the first Confederation Ministry, and did so.

Their day of reckoning soon came. On June 27, a few days before

Confederation became effective, they attended the Upper Canada Reform

convention in Toronto, were harshly treated by the delegates when they

spoke, and were read out of the party for their alleged “treachery.”

George Brown was the chief instrument of their undoing. He roused the

audience to indignation against his quondam friends. An impressive

picture of his appearance and denunciation of Macdonald on this occasion

is given by Sir George W. Ross:

“I remember well his tall form and intense earnestness as he paced the

platform, emphasizing with long arms and swinging gestures the torrent

of his invective. His manner was so intense, because of its flaming

earnestness, as to overshadow the cogency and force of his arguments.

Every sentence had the ring of the trip hammer. Every climax smelt of

volcanic fire— sulphurous, scorching, startling—and the response was

equally torrid."

Alongside George Brown’s services for Confederation must be placed his

work for the acquisition of the Northwest Territory. He became

interested in this question soon after his arrival in Canada, and in

1847 The Globe published in full a lecture by Robert Baldwin Sullivan,

who knew the value of the country, and pointed out the danger of the

westward trek of Americans resulting in their occupation of that

territory. Brown referred to the Northwest in his opening speech in

Parliament in 1851, and in 1852 The Globe published an article declaring

that the exclusion from civilization of half a continent for the benefit

of shareholders was unpardonable. The agitation was kept up despite the

jeers of less discerning editors and politicians. In a speech at

Belleville in 1858 Brown said:

“Sir, it is my fervent aspiration and hope that some here to-night may

live to see the day when the British American flag shall proudly wave

from Labrador to Vancouver Island, and from our own Niagara to the

shores of Hudson Bay.”

The seed had been sown largely through the vision and persistence of

Brown, and the acquisition of the Northwest came in 1869, through the

medium, it is true, of other hands.

Brown’s public life virtually ended at Confederation by his defeat in

South Ontario in 1867. Already in May of that year he had looked forward

to the freedom of retirement when in a letter to L. H. Holton of

Montreal he said: “My fixed determination is to see the Liberal party

reunited and in the ascendant, and then make my bow as a politician. . .

. To be debarred by fear of injuring the party from saying that is unfit

to sit in Parliament, and that is very stupid, makes journalism a very

small business. Party leadership and the conducting of a great journal

do not harmonize.”

Brown thereafter gave little attention to politics except through The

Globe. He left the party leaders free, save when they sought his advice,

which was freely given. He was appointed to the Senate in December,

1873, but took little part in its proceedings. He found it a dreary and

uninspiring place, and in writing of his reciprocity speech there in

March, 1875, he said, “it was an awful job,” and that “the Senate is so

quiet.” In the critical election of 1872 he made but one speech. He

divided his interest between his newspaper and his high-class Bow Park

Farm at Brantford. Here he spent happily the evening of his life, his

hours filled with peace after the fretful years of politics.

Mr. Brown was the second Father of Confederation to die at the hand of

an assassin. D’Arcy McGee was shot in 1868; Mr. Brown was wounded by

George Bennett, a discharged employee, on March 25, 1880, and died on

May 10, following. The country was grieved at the tragic ending of so

useful a career, and in the common sorrow criticism was stilled. A

politician who gave and received hard knocks was, after all, a

warm-hearted husband and father, and a man known and personally loved by

tens of thousands of his fellows. His passing caused a wave of regret,

and the years have effaced party feeling and steadily magnified his part

in laying the foundation of the expanding Dominion. |