|

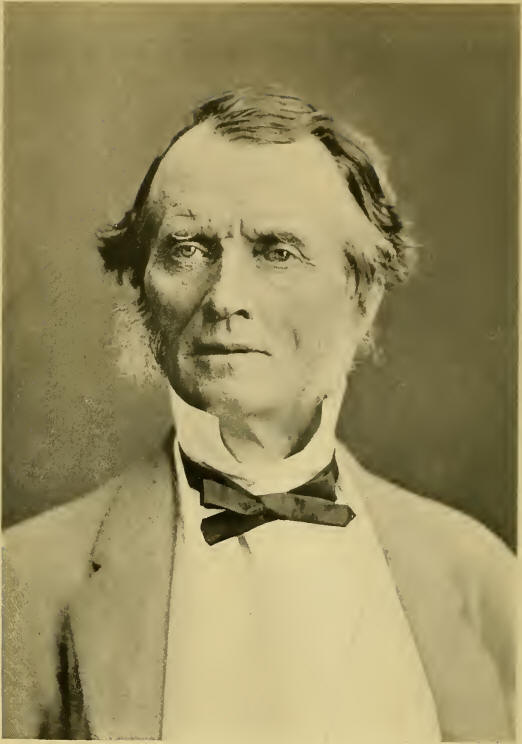

(1812-1872)

THE “Sandfield

Macdonald surplus” was for almost a generation a monument to the

principles and parsimony of the first Premier of Ontario. During its

accumulation its fate was ever the subject of teasing and speculation by

the Reform Opposition. In after years the Conservatives never failed to

discount the savings of the Mowat Government by laying credit to the

economies of John Sandfield Macdonald. How a surplus of three million

dollars could be gathered in four years from the frugal revenues of that

period will ever remain a mystery to the spenders of to-day. With

Sandfield Macdonald, retrenchment was a religion, and formed one of his

vows on taking office. It was a justified and natural course in a new

commonwealth barely emerged from pioneering, when food was plentiful but

money was indeed scarce.

Sandfield Macdonald was opposed to Confederation until its passage was

assured; then, with the ready adjustment which marked his whole career,

he accepted it and responded to Sir John A. Macdonald’s call to form the

first Government for Ontario. He was in public life almost continuously

from 1841 till his death in 1872, was Premier of Canada for two years in

the early ’sixties, and participated freely in the complex movements

which preceded Confederation. By temperament he was unsuited to the

compromises of office.

Conscious of this fact, he early described himself as a “political

Ishmaelite.” In an era when political lines were indifferently defined,

he frequently shifted his allegiance. In 1864 he moved the resolution in

the Reform caucus requesting George Brown to join the coalition

government to promote Confederation, but failed to recognize that this

implied sanction of the movement. His advancement in public life was due

to native ability—, courage and undoubted integrity, to popularity among

the Highlanders of eastern Ontario, and to his adherence to his own

opinions. He was caustic of speech and often irascible, though he was

capable of geniality and craft in settling political problems that

confronted him.

During most of his political life he was in opposition to George Brown,

and at times exhibited jealousy of the Reform leader. While driving from

Guelph to Elora to attend a meeting after the formation of the Brown-Dorion

Government, a party of Reform leaders, including Sandfield Macdonald,

Dorion, Mowat, Holton and others, were met by a reception committee en

route. One of these, Col. Charles Clarke, who relates the story, made a

general inquiry as to why Brown was absent. “Can’t you do without Brown

for a single night?” came the snappish reply from a voice within the

carriage, and the voice belonged to Sandfield Macdonald.

In 1858 John A. Macdonald, in a courteous and kindly letter, asked

Sandfield Macdonald to join his Cabinet, offering him a choice of

portfolios. The reply was a brusque telegram, saying simply: “No go.”

In spite of this, Sir John Macdonald had a kindly feeling for his

namesake, and in 1863, while battering the walls of the Sandfield

Macdonald-Sicotte Government in its declining days, was at pains to

state that he bore no personal feeling against the head of the

administration. The same kindly attitude—combined, it may be, with

political sagacity—led Sir John to ask Sandfield Macdonald to form the

first Cabinet in Ontario. The two new Premiers faced the electors in

their respective spheres in 1867, in what the Liberals resentfully

described as “hdnting in couples.” The one condition imposed by Sir John

was that the new Ontario Cabinet should be a coalition government, which

was to include two Conservatives, and three Reformers, including the

Premier. This condition led to bitter attacks by the Reform press, which

generally followed Brown’s lead in his denunciation of the “Patent

Combination,” as Sandfield Macdonald named his own Cabinet.

The opposition of Brown and the bulk of the Reform party drove Sandfield

Macdonald substantially into the Conservative camp, and his

administration suffered a raking fire from Edward Blake and Alexander

Mackenzie, then in their prime as destructive critics. Sir John

Macdonald was at this time in poor health, and his last recorded

references to his protege before the latter’s death were of sorrow and

disappointment at the overthrow of the Government in Ontario, whose head

refused to take advice. Writing to John Carling a few days after the

Government had resigned in December, 1871, Sir John said:

“There is no use ‘crying over spilt milk,’ but it is vexatious to see

how Sandfield threw away his chances. He has handed over the surplus,

which he had not the pluck to use, to his opponents; and although I

pressed him on my return from Washington to make a President of the

Council and a Minister of Education, which he half promised to do, yet

he took no steps towards doing so.”

John Sandfield Macdonald was a proud and fitting product of his

environment. He was born at St. Raphael’s, Glengarry County, Ontario, on

December 12, 1812, his father being a Highlander and a Roman Catholic.

It was characteristic of Sandfield that he attempted to run away from

home while yet a boy, and when his service in a Cornwall store led to

gibes from other boys at the “counter-hopper,” he quit the store and

took up the study of law. His education at this time was most imperfect,

but so keen was his mind that in eight years, or by 1840, he was

admitted as an attorney. The idol of the settlement, he soon developed a

profitable practice and in 1841 was elected to the Assembly. His

popularity with his constituents was without limit, and they returned

him again and again, either by acclamation or with sweeping majorities,

and once drove his opponent from the riding. He was an irresistible

campaigner in his own riding, and his methods were not without

originality. For electioneering journeys he secured a flimsy old

vehicle, tied up its wheels with cord, and went among his people saying:

“I am one of yourselves.” Though he lived in comfort for those days, the

farmers respected him for his success, and listened gladly to his

hesitating but pungent speech. He was a keen student of human nature,

and once when leaving home for a few weeks enjoined the chief town

“rough,” whom everyone feared, to guard his premises. The trust reposed

in him led the incorrigible to half kill several prowlers. Macdonald’s

standing in Glengarry was heightened by addresses to the electors in

Gaelic, a form of appeal used to advantage by other public men in the

Scottish settlements of Ontario up to recent years.

This tall, slight, impulsive young lawyer, with the massive head,

speedily attracted notice in the Assembly of the new Union of Canada. He

seconded the Address in September, 1841, and immediately joined in the

Reformers’ fight against Sir Charles Metcalfe and the “Family Compact.”

In 1849 he became Solicitor-General for Upper Canada. When the

Hincks-Morin Government was organized in 1851 the portfolio of

Commissioner of Crown Lands was offered to him, but he declined, seeking

unsuccessfully the post of Attorney-General West. Although he was

elected Speaker, he held a grudge against Hincks for the fancied slight,

and in 1854 recorded an adverse vote on the Address, and thus forced

Hincks to resign.

An illustration of Macdonald’s courage and independence was his advocacy

of non-sectarian education, and for opposing Separate Schools he

incurred the denunciation of his Church. Though brought up a Roman

Catholic, he was not a specially devout church member, and laughingly

referred to himself as “an outside pillar.”

Political alliances were often of unstable character in those days of

deadlock. Though Sandfield Macdonald and George Brown had opposed each

other for years, in 1858 the feud was healed and Macdonald joined the

Brown-Dorion Government as Attorney-General West. Brown and Macdonald

soon separated and the gulf between them steadily widened. During the

succeeding Cartier-Macdonald regime, Sandfield Macdonald alternately

attacked the Government and the Opposition. When that Administration

resigned in March, 1862, the Governor-General, much to the people’s

surprise, asked Sandfield Macdonald to form a Cabinet. The Macdonald-Sicotte

Government was the result.

The new Premier faced the abashed country with an extensive program. He

called for the “double majority,” a higher tariff for revenue purposes,

retrenchment in expenditures, a new insolvency law, and a new militia

bill, but his silence on representation by population offended the Upper

Canadians and led to vigorous attacks by George Brown and The Globe.

This dissatisfaction grew as the months passed, and in the following May

the Government went down under a double fire from John A. Macdonald on

one side and George Brown on the other.

Instead of resigning and retiring, the Premier came up with

reconstruction. The expelled Ministers promptly joined the Opposition,

and by March 21, 1864, the Sandfield Macdonald-Dorion Government

resigned without even a want of confidence motion. Macdonald’s speech

announcing the resignation of the Government possessed a wistful note.

“The time has come,” he said, after reciting their troubles, “when we

ourselves should make a fair acknowledgment of the difficulties in which

we are constituted and place our resignations, as we have unanimously

done to-day, in the hands of His Excellency.”

“Hear, hear. It ought to have been done long ago,” broke in D’Arcy

McGee, cruelly.

“If I have said anything with the appearance of malice,” the Premier

added, “I did not intend it in the sense in which it may have been

understood. I owe no grudge against anyone on the other side. I desire,

so far as I am concerned, to give and take, and shall be as ready to

forget as to forgive injuries.”

Sandfield Macdonald’s opposition to Confederation was captious rather

than profound. It is true he maintained that union ought not to be

effective without submission to the people, but his various speeches

during the debates of 1865 were marked by petty criticism. The delegates

from the Maritime Provinces, he said, had gone to Charlottetown to form

their own union, and their deliberations were interrupted by the members

of the Canadian Government, who offered them greater inducements and

undermined the plans for which they had met. The minds of the people of

Canada, he said, had been unhinged by the proceedings of the past year,

and political parties had been demoralized. “The Reform party,” he

declared, “has become so disorganized by this Confederation scheme that

there is scarcely a vestige of its greatness left. ... I never was

myself an advocate of any change in our constitution; I believed it was

capable of being well worked to the satisfaction of the people, and we

were free from demagogues and designing persons who sought to create

strife between the two sections.”

This disinclination to countenance change gives Sandfield Macdonald the

color of a reactionary, despite his place in the Reform party during

most of his public life. Sir James Whitney, who studied law in

Macdonald’s office, used to say that he was by habit of mind

Conservative rather than Liberal.

Although Sandfield Macdonald’s comments on Confederation revealed a

waspish habit of speech, there was much humor which the solemn 1865

Assembly enjoyed. He attacked the Coalition Government then in power,

and said its record would be as bad as that of 1854.

“Who moved that the honorable gentlemen representing the Liberal party

should go into the Government?” asked Alexander Mackenzie,

significantly.

“I found they were going—that the honorable gentlemen had full speed and

that nothing could restrain them,” was the evasive reply.

Annexation talk was prevalent in the Maritime Provinces at this time,

and Sandfield Macdonald used this fact in arguing against Confederation.

If an attempt were made to coerce them to join Canada, he said, they

would be like a damsel who is forced to marry against her will, and who

would in the end be most likely to elope with someone else.

“Sir,” he added with dignified emphasis, “it has been my misfortune to

have been nearly nineteen years of my political life in the cold shades

of Opposition, but I am satisfied to stay an infinitely longer period on

this side of the House if that shall be the effect of my contending for

the views which I have expressed.” Even the enactment of Confederation

was slow to mellow Macdonald’s opposition, though he became at once a

Provincial Premier. On July 23, 1867, speaking at Greenwood, in South

Ontario, he said the new constitution “would not remedy the evils

complained of in the past, but would increase them.”

Macdonald’s political position was anything but clear from his addresses

at this time. “If the Conservatives expected I would yield to them,” he

said at Greenwood, “they were mightily mistaken.” He said he was the

most obstinate man in existence except George Brown, and yielded his

opinions to nobody. He would like to see “John A.” or anybody else

dictate to him the course he would follow.

Late in August, in his nomination speech at Cornwall, Sandfield

Macdonald spoke of the peaceful revolution in Canada as evidence of the

high enlightenment of the people and of their eminent fitness for

self-government. He sincerely hoped there might be no cause to regret

the step taken. He had said in the last session that “now that the

change was accomplished, he would give all the aid he possibly could to

the new constitution.”

When Sandfield Macdonald met the Legislature in the autumn of 1868 he

startled the House with his radical program. He proposed and put through

measures to abolish the property qualification for members of the

Legislature to establish one-day elections, increase free grants to

settlers from 100 to 200 acres, and to sweep away legislative grants to

sectarian institutions. Problems of drainage, boundary awards and

settlement of accounts with Lower Canada crowded on the Government

during these early days of Ontario.

As the years passed, the Premier was growing petulant and at times gave

offence to deputations by his outspoken utterances. A famous instance is

when a party of men from Strathroy asked for a grant and were met by the

insolent query, “What the h— has Strathroy done for me?” In the

elections of March, 1871, the Liberal Opposition made undoubted gains.

They claimed to possess a majority, though the same claim was made by

the Government. When the House met on December 7 there were eight

vacancies, and Premier Macdonald played for time that these might be

filled. The Opposition, however, saw their chance, and bombarded the

Government with want of confidence motions. The Government were unequal

to the struggle. Their railway subsidies were especially attacked, and

four times they failed to secure a majority on divisions. Edward Blake,

then Liberal leader, demanded a declaration of policy with regard to the

surplus, and said the country was crying out for its disposal. Alexander

Mackenzie and Sandfield Macdonald indulged in recriminations as to

whether the latter had betrayed the Reform party, and who was really the

leader of that party. Macdonald said that he was “now and since 1867 had

been denounced simply because he organized his own party and manned his

own ship.”

One of the Ministers, E. B. Wood, gave way under the storm and resigned,

and finally on December 19 the Premier announced that he and his

colleagues had handed in their resignations. Then, in a rather painful

scene, as all recognized that the end of a long, useful public career

had come, concurrently with physical weakness, the Premier “appealed to

the honorable gentlemen opposite if he had said anything of a personal

character in the heat of the debate which had given offence, he asked

forgiveness now, as he had intended no offence and hoped that this would

be accepted as an apology, and if they were as ready to forgive as

himself, it would be mutual.”

Edward Blake succeeded to the Premiership of Ontario; Sandfield

Macdonald retired to his home in Cornwall, where he died on June 1,

1872, his end hastened by the sting of defeat. He was buried among his

beloved Highlanders.

Sir James Whitney, as Premier of Ontario, speaking at the unveiling of a

monument to John Sandfield Macdonald in Toronto, in November, 1909,

said:

“Mr. Macdonald was a man of great force of character and individuality.

These were his dominant characteristics. Once he formed an opinion or

came to a conclusion, it was not easy to turn him aside. Consequently

party limitations and conditions galled him, and as a rule he went his

own way and voted as he thought proper. The position he occupied in the

political world was indeed unique.”

On the same occasion, The Globe, writing of Mr. Macdonald, for so long a

political opponent, said: “It fell to Mr. Macdonald’s lot to organize

the public service of this Province and give direction to its

legislation. How well he did this work is best shown by the fact that

the lines he laid down and the precedents he set have never since been

greatly departed from.” |