|

(1814-1873)

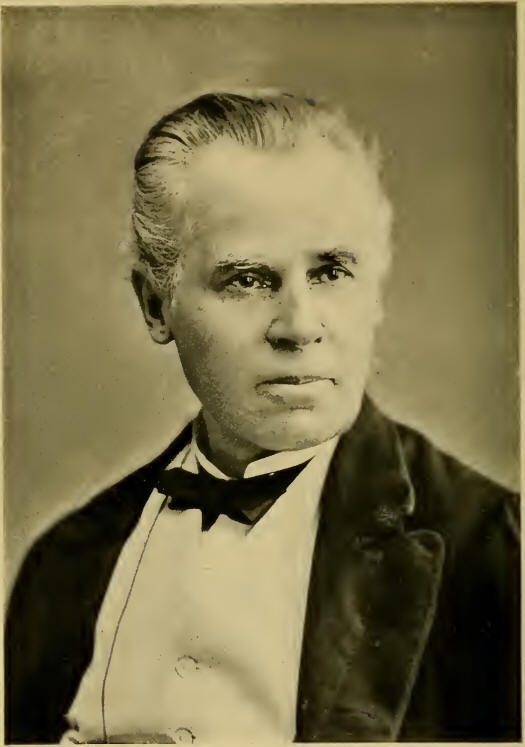

SIR GEORGE ETIENNE

CARTIER sprang from stock whose roots were thrust deep in Canadian soil.

His family, who, according to legend, were collateral descendants of

Jacques Cartier, the discoverer of Canada in 1534, had lived in the St.

Lawrence valley for nearly two centuries. Their later home by the

Richelieu was on the great secondary highway of the ancient regime. Here

settled in 1672 the officers of the Carignan-Salieres regiment, their

light blue uniforms and courtly manners soon to give place to the

homespun and the neutral tints of a pioneer life. Nearby Beloeil lifts

its shadowy mass above a wide, flat landscape, and the Richelieu gurgles

complain-ingly over the rapids at Chambly as if in distress for its lost

prestige.

Such an atmosphere naturally created in a youth a strong love of French

Canada, his homeland. Cartier was to Lower Canada what Brown was to

Upper Canada, a leader devoted to the interests of his own people, and

who upheld them even at the cost of alienating the neighboring Province.

Brown roused Upper Canada into resentment against the French-Canadians.

Cartier resisted Brown’s demands for representation by population until

deadlock and coalition raised both above party warfare and Confederation

resulted. While Brown declared the union of 1841 a failure and demanded

its repeal, Cartier as firmly defended it and insisted on the

maintenance of equal representation.

It is instructive to compare Cartier with a great French-Canadian of a

later day. Cartier was fiery, impetuous, full of energy; Laurier is

serene, dignified and quietly efficient. Cartier led his people to

Confederation in face of powerful opposition, but supported by the

clergy; Laurier led Quebec in 1896 for toleration, despite the influence

of the Roman Catholic Church. Cartier plodded patiently through a

codification of laws and promoted the construction of the Grand Trunk

Railway; Laurier inspired a great immigration policy to fill Canada’s

waste spaces, and projected a second transcontinental railway to give

breadth as well as length to the Dominion. Each was of Canadian stock of

many generations, but each rose to the call of his time in his national

and imperial duty. Cartier’s day ended just as Laurier’s sun appeared

over the morning horizon.

After bitterly resisting Brown’s plan of representation by population

because, he said, it would be unjust to Lower Canada, Cartier joined

hands with Brown in 1864 for the greater union of the British North

American colonies. For his vision and statesmanship he paid the usual

price demanded by smaller minds. He was accused of inconsistency, but he

replied that he did not regret his earlier decision. He was taunted with

sacrificing his race, but he responded that he was safeguarding their

nationality and their religion. He was opposed by influential men of

both races in his own Province, until almost alone among the influential

men, he carried the banner of union.

Fortunately for Confederation, it was favored by the Roman Catholic

authorities. That most conservative influence now rallied to the side of

British institutions, as against the dangers of American republicanism,

just as it had rejected the overtures of Washington and D’Estaing during

the American Revolution. Without Cartier’s influence Confederation could

not have carried in Lower Canada, at least without delay, and without

Lower Canada it could not have become a fact. Cartier was honestly a

convert to union at the hand of A. T. Galt. That champion of

Protestantism gave a powerful speech for union in 1858. Cartier, who

soon thereafter become Premier of United Canada, was so impressed he

asked Galt to join his Cabinet. Galt did so on condition that union

would become a Cabinet question. Cartier kept his word, and in 1859 made

the first definite step towards union by despatching a mission to

England on the question, consisting of Galt, Ross* and himself. These

delegates urged action by the Imperial authorities, but to their

approaches the Maritime Provinces, save Newfoundland, responded that

they were not yet ready to discuss the question.

A network of electric and steam railways now pierces the alluvial valley

of the Richelieu, once the highway of blood-thirsty Iroquois, and the

home of Madeleine de Vercheres and her brave pioneer compatriots. Walls

of old stone windmills that creaked as they ground the habitants’ grain

still dot the landscape.

It was here at St. Antoine that George Etienne Cartier was born on

September 6, 1814. His grandfather, Jacques Cartier, was a man of some

means, an exporter of wheat to Europe. The home was called “The House of

Seven Chimneys,” and in it centred the social life of the community.

Here gathered the thrifty, simple-living habitants and joined in folk

songs, such as “A la Claire Fontaine,” luring, if weird, compositions

that prevail to this day in Quebec, and constitute the only Canadian

folk songs worthy the name. Cartier, even in his later years, had a good

singing voice, and his own contribution to the music of his country, “O

Canada, Mon Pays, Mes Amours,” written at the age of twenty, is still a

popular song in his Province. Cartier’s father was a man of genial

spirit and his mother a woman of intelligence and piety. They realized

the advantages of education, and when George was in his tenth year he

was sent to the Montreal College, where he remained for seven years,

graduating in law in 1835.

At this time Lower Canada was aflame with the agitation for responsible

government which culminated in the rebellion of 1837. The magnetic

Papineau was the hero of hundreds of eager young minds. Cartier was soon

to fall under his spell and take up the campaign against the conduct of

the Governor and the Executive Council. Popular demonstrations against

the authorities began in the spring of 1837, even the sedate Louis

Hippolyte Lafontaine declaring:

*Louis Joseph Papineau, (1786-70), a tribune of the people in Lower

Canada, whose agitation against executive tyranny resulted in rebellion

in 1837, followed by an inquiry and the granting of responsible

government.

“Everyone in the colony is discontented; we have demanded reforms and

not obtained them; it is time to be up and doing.” The Sons of Liberty

had attracted the impetuous support of Cartier in the 1834 elections,

and he became the bard of the movement, composing the song, “Avant tout

je suis Canadien” (“Before all I am a Canadian”). It will thus be seen

that French-Canadian indifference to the outside world is of long

duration. Cartier, however, lived to be a rigid constitutionalist and

stout champion of British connection. Indeed, he never admitted his part

in the rebellion of 1837 was due to antipathy to Britain, but rather to

the tyrannical government which then prevailed in Canada. Dr. Wolfred

Nelson became the militant head of the rebellion in Lower Canada. He was

a Montrealer, of English origin, 6 feet 4 inches tall and generally

popular. In the skirmishes on the Richelieu Cartier was his aide, and at

the fight at St. Denis brought reinforcements across the river. When the

uprising failed Cartier fled towards the American boundary and later to

Plattsburg, N.Y., whence he returned a few years later when the

“patriots” had been forgiven.

A man of Cartier’s ardent temperament was quick to attach himself to a

worthy cause, and Papineau having ceased to b6 a political factor he

allied himself in the early ’forties with Lafontaine, who, with Robert

Baldwin, was called on to form a government—a responsible government—in

1848. This was, as F. D. Monk has said, “the blessed day of the birth of

free government for our country, the true birth of our nation.”

Cartier was now 34 years old, a successful lawyer, and a man of

boundless energy. He had already worked on the fringe of politics, and

in 1848 was elected to Parliament for the constituency of Vercheres. He

entered the Assembly the next year, in time for the bitter debates over

the Rebellion Losses Bill, ending in the burning of the Parliament

buildings at Montreal on April 25. Cartier took little part in this

struggle, and he was not one of the signers of the manifesto favoring

annexation to the United States which was prepared that year by

prominent Montreal men in their Gethsemane of political disappointment.

Responsible government had been secured, and the next reform sought was

the abolition of seigniorial tenure. Cartier supported Baldwin and

Lafontaine in this cause, which finally triumphed in 1854.

From then on, Cartier was almost steadily in office until his death. His

law practice had given him a financial foundation and enabled him to

live up to one of his beliefs that “property is the element which should

govern the world.” The all but universal suffrage which prevailed in the

United States was to him a matter of abhorrence. He joined the

MacNab-Tache Government in 1855 as Provincial Secretary, and in 1857

became Lower Canada’s leader in the Macdon-ald-Cartier Cabinet. During

this period of prosaic service Cartier, while not himself a great

jurist, carried through the codification of the civil laws and laws of

procedure of Lower Canada, a work of several years and of the utmost

value in a country of diverse races. When this task was completed in

1864 Cartier rose like a weary Titan and said: “I desire no better

epitaph than this: ‘He accomplished the civil code.” His effort to pass

a militia bill providing for an active force of 500,000 to drill 28 days

per year savored too much of militarism even in 1862, when Canada was

threatened from the warring republic to the south. The Government was

defeated on the issue and resigned.

In the great transportation movement of the day, the building of the

Grand Trunk Railway, Cartier took an aggressive part, corresponding to

that of Sir Charles Tupper with the Canadian Pacific a generation later,

or of Sir Wilfrid Laurier with the Grand Trunk Pacific in 1903. In 1852

he presented two acts in the Legislature, one to incorporate the Grand

Trunk Railway Company, to build between Toronto and Montreal, and the

other to incorporate a company to construct a railway from opposite

Quebec to Trois Pistoles, and for the extension of such railway to the

eastern boundary of the Province. As early as 1846 he had been an ardent

advocate of railway building, and in 1849 said, with vision:

“There is no time to be lost in the completion of the St. Lawrence and

Atlantic road if we wish to secure for ourselves the commerce of the

West.”

During the construction of the Grand Trunk the company’s credit on

several occasions became dangerously low, and Cartier led in the

agitations for aid. For several years he was the company’s legal

adviser, but to criticism of this anomalous position for a Cabinet

Minister he replied that the company was too poor to pay even a

dividend.

Anyone familiar with lumbering operations in Canada knows the nature of

a log jam. Timber dumped into a river floats down stream freely until it

strikes an obstacle, when the logs pile up and make a blockade and

seemingly hopeless confusion, only to be cleared when the “key log” is

removed. The events leading up to the early ’sixties in Canadian

politics may be likened to a log jam. Political cliques and the

dominance of small issues, quarrels and jealousies between leaders,

stagnation in public business—all these created a hopeless situation

that called for decisive treatment. Men of outlook in all parties saw

the solution in a revolution which would bring about the union of the

British American Provinces. Where was the “key log” of this confused

situation? It was found in the idea of a coalition which was proposed

and realized in 1864. George Brown had been pressing for years for

representation by population, as Upper Canada was increasing much more

rapidly than her sister Province, but to all these appeals Cartier

turned a stony heart.

“Has Upper Canada conquered Lower Canada?” he asked in 1858, and added,

menacingly, “Lower Canada will adopt other political institutions before

submitting to such a motion as that of the member for Toronto” (Brown).

In 1861 Cartier admitted that Upper Canada had 400,000 to 500,000 more

population than Lower Canada, and if that progressive increase

continued, it might be necessary to modify the nature of the union, but

a year later, in a fiery reply to a similar demand from Upper Canada, he

said he and John A. Macdonald were in agreement on the question and they

“demanded the support of this House to maintain that equality which is

the only foundation of the union.”

Cartier’s obstinate rejection of Upper Canada’s demands made the finding

of the key log in the legislative jam all the more urgent. It came when

Brown offered to join with any government to put union on the

legislative program. Cartier, the “little corporal” of Lower Canadian

politics, the defender of the most conservative element in the two

Canadas, the man who had gone to Ontario in 1863 to boldly challenge

Brown and expound the French-Canadian viewpoint in the enemy’s

country—Cartier laid down his arms and entered into the negotiations

which resulted in the coalition government.

This resolution on the part of violent opponents to work together- for

the common good, though an inspiring spectacle in the light of history,

created astonishment and resentment among people who were too near great

events to appreciate their significance. For the moment, however, the

feeling of relief at the breaking of the deadlock overcame opposition,

and the preliminaries to Confederation proceeded with despatch. The

memorandum sent by Cartier and his colleagues to the Colonial Secretary

in 1858 asking for Imperial sanction of union was the first practical

step. This had been followed by Brown’s alternative plan to federalize

United Canada by two or more local governments, with some joint

authority to control matters common to both Provinces. When the issue

was finally forced in 1864, Cartier’s importance was derived largely

from his power in Lower Canada, though in framing the resolutions he was

a weighty factor in securing a federal rather than a legislative union.

Sir Richard Cartwright, speaking in Parliament in 1881, acknowledged the

services of Cartier in these words:

“I believe that, save one other man, he (Cartier) did more, he risked

more, he sacrificed more to bring about Confederation than any other man

in Canada. The only man who risked as much and sacrificed as much as he

did was the late Hon. George Brown. To these two gentlemen, I believe,

the Confederation of these Provinces was largely due, and I am bound to

say that to both of them, in that respect, this country owes a great

debt of gratitude.”

Cartier joined his Canadian colleagues in attending the Charlottetown

and Quebec Conferences in 1864. It is doubtful if any of them fully

realized the full meaning of their mission as their steamer sailed into

Charlottetown harbor that September morning, bearing Canadians to confer

with the delegates from the Maritime Provinces. Before they returned,

however, Cartier, speaking at a banquet, expressed the hope that there

would result from their deliberations “a great confederation which will

be to the benefit of all and the disadvantage of none.”

It is a part of the history of the period that the new idea was not

quickly adopted, and, magnificent as was the vision of the eloquent

promoters, years passed in the Maritime Provinces before union was

sanctioned by the people. At the Halifax banquet a few days later

Cartier reached a high note.

“We can form a vigorous confederation whilst leaving the provincial

governments to regulate local affairs,” he said. “There are no obstacles

which human wisdom cannot overcome. All that is needed to triumph is a

strong will and a noble ambition. When I think of the great nation we

could constitute if all the provinces were organized under a single

government, I seem to see arise a great Anglo-American power. The

Provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia represent the arms of the

national body embracing the commerce of the Atlantic. No other will

furnish a finer head to this giant body than Prince Edward Island, and

Canada will be the trunk of this immense creation. The two Canadas

extending far westward will bring into Confederation a vast portion of

the western territory.”

Though the Premier of Canada, Sir E. P. Tache, presided at the Quebec

Conference, Cartier was a more influential figure from Lower Canada. In

forming the resolutions, Cartier’s master stroke, says John Boyd, his

biographer, was in securing a federal instead of a legislative union,

which would have swamped French-Canadian interests. His own view was for

double chambers in the provinces, while Brown favored single chambers.

As a consequence Ontario has a single chamber Legislature while Quebec

followed Cartier’s idea.

The heavy artillery in the great Confederation fight in the Canadian

Parliament in 1865 was soon brought into action. Macdonald, Brown and

Cartier were early speakers, but they did not have it all their own way.

Powerful debaters took the opposite view, though the union cause

succeeded after seven weeks. Cartier’s speech was one of his greatest

efforts. He spoke in French and occupied three hours. He defended his

opposition to representation by population and said perpetual political

conflict would have followed its enactment. On the other hand, he did

not fear for French-Canadian interests under Confederation, even though

in a general legislature they would have a smaller representation than

all other nationalities combined. He saw dangers in the war then going

on in the United States, and said: “We must either have a confederation

of British North America or be absorbed by the American union.” The

duties of defence, he pointed out, could not be freely carried out

without a confederation.

Then followed a declaration showing the strong loyalty of the man who

less than 30 years before had borne arms against the Canadian

authorities:

“Is the confederation of the British North American Provinces necessary

to increase our power and to maintain the ties which attach us to the

mother country? As far as I am concerned I do not doubt it.” The

rejection of the temptations of Washington in 1775, he showed, was

“because the French-Canadians understood that they would preserve intact

their institutions, their language and their religion by adhesion to the

British Crown.” “If Canada,” he added, “is still a portion of the

British Empire, it is due to the conservative policy of the

French-Canadian clergy.”

Cartier went on to say—and it is a statement worth recalling in later

days of racial differences—that the clergy of Lower Canada were

favorable to Confederation. “Those of the clergy who are high in

authority, as well as those in humbler positions, have declared for

Confederation not only because they see in it all possible security for

the institutions which they cherish, but also because their Protestant

fellow-countrymen, like themselves, are also guaranteed their rights.”

All was going well for the union cause, but shadows lay ahead. The

trouble makers for Cartier were A. A. Dorion, L. H. Holton, L. S.

Huntington, Christopher Dunkin and other influential Lower Canadian

members, from all wings of the Assembly, who strongly opposed

Confederation. Dorion and Holton did not oppose the principle of union,

but declared the time not yet ripe. Holton denounced the scheme as one

which would “plunge the country into measureless debt, into difficulties

and convulsions utterly unknown to the present constitutional system.”

While he would not despair of his country, he looked, if union carried,

for “a period of calamity, a period of tribulation, such as it has never

heretofore known.”

Henri Gustave Joly opposed the scheme because he believed it would be

fatal to French-Canadian unity, while others accused Cartier of having

surrendered to George Brown, who was pictured as the inveterate enemy of

the race. H. E. Tachereau of Beauce, although elected a Government

supporter, opposed the union as “a death-blow to our nationality, which

was beginning to take root on the soil of British North America.”

Public meetings in the Province followed, in an endeavor to rouse

opinion against union, and in these Dorion was joined by L. A. Jette,

afterwards Lieutenant-Governor of Quebec, L. O. David, now a Dominion

Senator, and others. The opposition only confirmed Cartier in his

determination. After the resolutions had been adopted in both Houses he

joined Macdonald, Brown and Galt in a mission to England to discuss

Confederation, defence, reciprocity and other matters. In a speech in

London, he said:

“We desire the adoption of Confederation, not only to increase our

prosperity and our strength, but also to be in a better position to

participate in the defence of the British Empire.”

Another ministerial visit to England was necessary at the end of 1866 to

frame the British North America Act, and on their return in 1867 Cartier

in a speech at Montreal made public the important fact that the Canadian

constitution had been approved and confirmed by the British Parliament

in the form in which it was drawn by the delegates. This represented a

long step in colonial self-government. Cartier said:

“The Canadians" said the English Ministers, ‘come to us with a finished

constitution, the result of an entente cordiale between themselves, and

after mature discussion of their interests and their needs. They are the

best judges of what will be suitable to them. Do not change what they

have done; sanction their federation.’ Yes, that is the spirit in which*

England received our demand. We required her sanction; she gave it,

without hesitation, without wishing to interfere in our work.”

During a visit to England in 1868 Cartier supplemented this declaration

in a speech at the Royal Colonial Institute when he said:

“It is a great source—I will not say of pride—but a great source of

encouragement, to the public men who then took part in that great

scheme, that it was adopted by the English Government and by the English

Parliament, without, I may say, a word of alteration.”

When Confederation honors werse bestowed in 1867 Cartier declined to

accept the proffered C. B., declaring it to be insufficient and

therefore a slight to him as a representative of one of the two great

Provinces of Confederation. Considerable feeling was aroused in Quebec,

and shortly afterwards, on the intervention of Dr. Tupper, Cartier was

made a baronet. The irony of it was that he had to borrow the money

needed to pay the fees in connection with the decoration.

The elections of 1867 confirmed Quebec in her acceptance of

Confederation. Opponents of union main: tained their campaign before

voting, but Cartier was strongly supported by the Roman Catholic

ecclesiastics, both high and low, who threw the scale, as on previous

occasions, in favor of British rule and against any danger of

republicanism. Out of 65 seats in the Province the anti-unionists

secured only 12. Cartier was now Minister of Militia and Defence in the

first Confederation Cabinet, and was one of Sir John A. Macdonald’s most

trusted colleagues. He was a potent force in the construction of the

Intercolonial Railway, that much delayed highway, and contended for the

adoption of the northern, or Bay de Chaleur, route, both for commercial

and military reasons. His organization of the Canadian defence

prevailed, with additions, until the outbreak of the great war in 1914.

Cartier accompanied William McDougall, a colleague, to England in 1868

when the negotiation for the purchase of the Hudson’s Bay territory, now

comprising the great prairie Provinces of the West, from the Hudson’s

Bay Company, was carried out successfully. Owing to McDougall’s illness,

the bulk of the work fell on Cartier.

This was one of the last of the French-Canadian leader’s great

undertakings. He had much to do with the legislation connected with the

Pacific Railway scheme in 1872, and introduced the bill providing for

grants of 50,000,000 acres of land and $30,000,000 in cash, but before

it was implemented he had broken down with an attack of Bright’s disease

and sought treatment by London specialists. In the election of 1872

Cartier suffered a crushing defeat by L. A. Jette, a rising young

French-Canadian, whom he flouted by saying his conduct was “bold and

foolhardy.” Cartier’s aggressiveness on this occasion, his trouble with

the Church over a minor internal matter, and dissatisfaction over his

supposed desertion of the Catholics of New Brunswick, when non-sectarian

schools were established there, brought disaster. In the hour of his

humiliation he was forced to accept the seat of Provencher in Manitoba

at the hand of Louis Riel, the rebel leader of two years previous.

Cartier reached London in October, 1872, and was encouraged to believe

he would soon recover. His letters to Sir John A. Macdonald and others

were full of hope and even defiance. The old lion was cornered but not

cowed. In April the Pacific Scandal storm broke at Ottawa, and its

thunder and lightning reached the sick room in London. Cartier was

politically seriously compromised by the charges. He had been an

intimate of, and intermediary with, Sir Hugh Allan, head of the railway

syndicate, who, as was proved in the inquiry, had contributed $350,000

to the Conservative campaign fund, and thousands of it had gone to

Cartier’s war chest, though his personal honesty was never called in

question. He could not leave for Ottawa; he could not meet the charges

in London. He was marooned and condemned. He died on May 20, 1873, a

brokenhearted man.

Among Cartier’s associates there was genuine sorrow at his passing, but

party feeling at the climax of the scandal charges prevented crocodile

tears from his political opponents. His body was brought to Montreal and

given an imposing public funeral, after which his former colleagues had

to return to their own defence.

There was pathos in the death of Cartier. He had given his life to the

service of his country. For thirty-five years he had been in politics.

Much of that time he had labored incessantly, at high pressure for long

hours. Nature had gifted him richly for administrative work, and

leisurely colleagues were ever ready to use him as a pack-horse. His

body was the embodiment of nervous force and energy, his expression was

one of vivacity and animation. The “little man in a hurry” was of medium

height, strong and robust, of ruddy complexion, fastidious in dress and

commonly wearing the Prince Albert coat affected by public men of his

day. His courage was unbounded, his temperament dominating and absolute.

His wife, a daughter of Edward Raymond Fabre, of Montreal, a woman of

piety and devotion to her family of three daughters, survived until

1898.

Cartier stands as the representative of the masses of Lower Canada at

the critical hour of Confederation. A Catholic and strong champion of

his race, he was tolerant and even popular with Protestants. His vision

marked him a nation builder, his strategy enhanced his power as a

parliamentarian, his faithful performance of prosaic routine earned the

gratitude of a nation in its birth throes.

Sir George

Etienne Cartier, Bart.

His life and times, a political history of Canada from 1814 to 1873 by

John Boyd (1914) (pdf) |