|

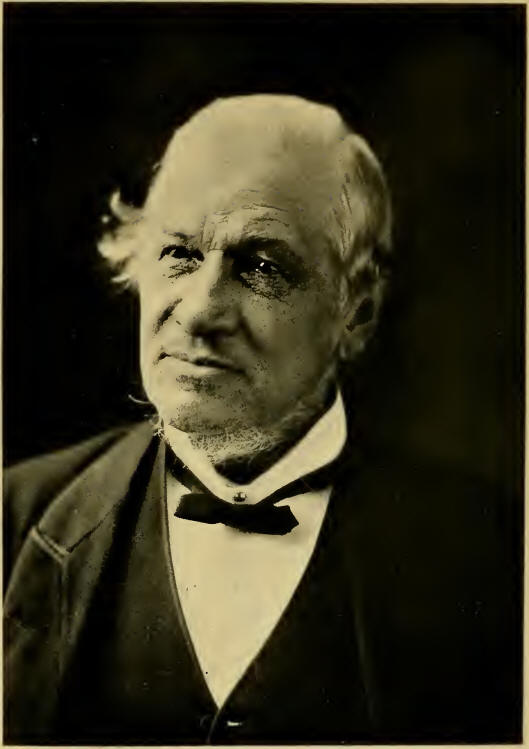

(1817-1893)

SIR ALEXANDER TILLOCH

GALT was a reservoir of ideas, a peerless exponent of finance and the

first man to force Confederation into practical politics in Canada. As a

father of protection, he penned a declaration of fiscal independence in

1859 which is one of the country’s steps in self-government. As the

first Canadian High Commissioner in London, he blazed a new Imperial

trail and proclaimed sentiments of loyalty which effaced the annexation

ideas of his early manhood. Throughout his public career he was the

champion of the Protestants of Quebec, and when he felt their rights

were prejudiced he resigned as Minister of Finance in 1866. His

constructive ability commanded general admiration, but fickleness and

independence robbed him of the fame and influence he deserved.

Galt’s portly, erect form was familiar for a quarter century of public

life, during which he counselled various leaders and supported different

ministries, but he never lost the respect of the people. His was the

generous, amiable personality of a robust, healthy man. He was a sincere

and earnest speaker, with a well-modulated voice and an amazing mastery

of facts, but he was not an orator. His diction was simple, without

flowers of eloquence, but was rather the cold, colorless language of the

economist.

Galt was essentially a practical man in politics. He left a successful

business and put at his country’s service a financial expertness rare in

public life. We think of Quebec as old and long settled, but Galt played

a large part in colonizing the Eastern Townships in the ’thirties and

’forties of last century. His father, John Galt, the Scottish novelist,

from whom he inherited his rich mental qualities, had preceded him in

the land business, being the founder and Commissioner of the Canada

Company, which colonized large tracts of the “Queen’s Bush” between

Toronto and Lake Huron and founded Guelph and Goderich.

Alexander Galt was born in London on September 6, 1817, and came to

Canada in 1834, as a junior clerk in the British American Land Company

at Sherbrooke. He rose step by step until in 1844 he became Commissioner

of the Company. He found its affairs in confusion, and by his ability

and understanding brought them to order and prosperity. His business

success attracted notice and in 1849 he was elected to Parliament for

the County of Sherbrooke. He sat through the stormy session of 1849,

when the Parliament Buildings in Montreal were burned, after the passage

of the Rebellion Losses Bill. This seemed to sicken young Galt of

politics for the time, for he retired to private life.

It was in 1849 that a group of influential Lower Canadians issued a

manifesto favoring annexation to the United States. A. T. Galt was one

of the signers of this document. It is easy now to condemn such an

extreme view of the country’s future, but Canadian prosperity was then

endangered by the adoption of free trade by Britain in 1846, and

Canadian pride was hurt by the indifference of British statesmen to

their colonies. It was then the fashion in Britain to say the colonies

cost more than they were worth. Galt was influenced, too, by a desire to

secure relief from the domination of the Catholic Church.

During the next four years Galt became President of the St. Lawrence &

Atlantic Ry., extricated it from its difficulties by amalgamation with

the Grand Trunk Ry., and participated in the construction of the Grand

Trunk from Toronto to Sarnia. From 1852 to 1859 he was a director of the

G.T.R. By 1853 he was back in Parliament, where he found scope for his

talents in financial, trade and commercial questions. Upon the fall of

the Brown-Dorion Government in 1858, Sir Edmund Head, impressed by

Galt’s striking speech that year in favor of a federal union, asked him

to form a Cabinet, but, realizing that his independent course, while

spectacular, left him without a following, he declined. George E.

Cartier, who was called on at Galt’s suggestion, took Galt as Minister

of Finance, promising to adopt federal union as a Cabinet policy. The

great issue of the time thus became a practical one.

Before tracing more in detail Galt’s contribution to Confederation, it

is instructive to note his services in forming Canada’s financial

policy. His first duty in taking office in 1858 was to restore the

shattered finances of United Canada. Revenues were low and expenses

high. It was his opportunity. Cayley, his predecessor, had been induced

by Isaac 8uchanan of Hamilton, the leading figure in the Association for

the Promotion of Canadian Industry, to give protection in the tariff to

several manufacturing industries. Galt went farther in 1859 and raised

the tariff from 15 to 20 per cent, on unenumerated articles. The object

of this tariff, he told the House on March 18, was “to encourage the

industrial portion of the community and to equally distribute the taxes

necessary for revenue purposes.” He ridiculed the idea that British

connection would be endangered, but before many months his policy had

made trouble in the old country and in the United States. An American

commission reported in 1860 that they were strongly impressed with the

lack of good faith shown towards the United States by Galt’s policy, and

Edward Porritt avers that feeling was so strong that even without the

Alabama case, the St. Albans raid and other episodes, the reciprocity

treaty would not have survived a day longer than it did.

If the United States was angry and retaliatory, the mother country was

sullenly acquiescent. Sir Edmund Head, in forwarding the new tariff to

the Colonial Secretary, was somewhat apologetic.

“I must necessarily leave the representatives of the people in

Parliament,” he wrote, “to adopt the mode of raising supplies which they

believe to be most beneficial to their constituents.”

Merchants of Sheffield protested against the new tariff and asked the

British Government to discountenance it as “a system condemned by reason

and experience.” The Duke of Newcastle, in forwarding the protest,

regretted that the law had been passed, but sa.d he would probably have

no other course than to signify the Queen’s assent to it. The Duke was

right, as he was pointedly told by Galt in the return mail.

“The Government of Canada,” Galt wrote, “acting for its Legislature and

people, cannot, through those feelings of deference which they owe to

the Imperial authorities, in any measure waive or diminish the right of

the people of Canada to decide for themselves both as to the mode and

extent to which taxation shall be imposed. . . . Self-government would

be utterly annihilated if the views of the Imperial Government were to

be preferred to those of the people of Canada. It is, therefore, the

duty of the present Government distinctly to affirm the right of the

Canadian Legislature to adjust the taxation of the people in the way

they deem best—even if it unfortunately should happen to meet with the

disapproval of the Imperial Ministry. Her Majesty cannot be advised to

disallow such acts unless her advisers are prepared to assume the

administration of the affairs of the colony irrespective of the views of

its inhabitants.”

Another important achievement by Galt at this time was the introduction

into Canada in 1858 of the decimal currency system, which replaced the

pounds, shillings and pence of the motherland.

There had been discussion of union of the British American Provinces for

years, but Galt forced the issue by his speech in the Assembly at

Toronto on July 6, 1858. He then outlined roughly the plan of union

which was subsequently adopted. He declared that unless a union was

formed the Province of Canada would inevitably drift into the United

States. He saw merits in the union of the two Canadas, which had

organized municipal government, settled the clergy reserves and

seigniorial tenure questions, and made the Legislative Council elective.

Yet the present Government, the strongest for several years, were unable

to carry their measures. The present system could not go on, it was

necessary to change the constitution, to adopt the federal principle.

Questions of religion and race now promoted disunion. If they adopted

the federal principle each section of the union might adopt whatever

views it regarded as proper for itself.

Canada, he said, looking to the future, was the foremost colony of the

foremost empire of the world. But in five months they had disposed of

measures that should have been passed in as many weeks. They had not

been able to take up the great subject of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and

unless they extended themselves east and west and made one great

northern confederation they must be content to fall into the arms of the

neighboring federation. Was it nothing to them to control all this

Hudson’s Bay territory? Such a thing was never known before that a

continent ten times as large as Canada was offered to a state. He

desired to see a wide and grand system of federation for the British

North American colonies. He believed a universal desire prevailed that

we should be no longer a colony—that we were fit for the dignity of

nationhood. And to such an aspiration no bar was offered by the Imperial

authority. He had no proclivities for office, he said. He only wished to

see the necessary policy for the country adopted, and he would give his

best support to any government who would carry out those principles.

Galt presented a resolution favoring federation, in part as follows:

“It is therefore the opinion of this House that the union of Upper with

Lower Canada should be changed from a legislative to a federative union

by the subdivision of the Province into two or more divisions, each

governing itself in local and sectional matters, with a general

legislature and government for subjects of national and common

interest.”

He also proposed:

“That a general confederation of the Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova

Scotia, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island with Canada and the

western territories is most desirable and calculated to promote their

several and united interests by preserving to each Province the language

control, management of its peculiar institutions and of those internal

matters respecting which differences of opinion might arise with other

members of the confederation, while it will increase that identity of

feeling which pervades the possessions of the British Crown in North

America.”

Strange to say, this clear-cut program attracted little notice at the

time. George Brown said he preferred representation by population, but

failing that he would take federal union of the Canadas. A little later

Galt entered Cartier’s Cabinet, taking with him the policy of

federation. Cartier, in announcing his Cabinet’s program, gave definite

form to the policy when he declared:

“The expediency of a federal union of the British North American

Provinces will be anxiously considered, and communications with the Home

Government and the Lower Provinces entered into forthwith on this

subject.”

At this time the climax of the deadlock had not been reached, but

political rivalries and racial jealousies were fast bringing about an

impasse. There were able men in plenty in public life, but the

inequalities between Upper and Lower Canada were causing ill-feeling and

anxiety, with no solution in sight. Cartier implemented his promise, and

with Galt and John Ross went to England. Their memorandum to the

Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, urged confederation on

grounds peculiar to Canada and considerations affecting the interests of

the other colonies and the whole empire. It referred to the demand for

increased representation for Upper Canada, which had resulted in “an

agitation fraught with great danger to the peaceful and harmonious

working of our constitutional system, and consequently detrimental to

the progress of the Province.” The memorandum set forth the desirability

of uniting Canada, the Maritime Provinces and Newfoundland, and added:

“The population, trade and resources of all these Provinces have so

rapidly increased of late years, and the removal of trade restrictions

has made them in so great a degree self-sustaining, that it appears to

the Government of Canada exceedingly important to bind still more

closely the ties of their common allegiance to the British Crown, and to

obtain for general purposes such an identity of legislation as may serve

to consolidate their growing powers, thus raising in the British Empire

an important federation on the North American continent.”

Little encouragement followed this formal appeal. The Colonial Secretary

showed no enthusiasm for the union, and writing a month later said the

Imperial Government could go no further at present, as they had received

a reply on the subject from only one Province.

Other events were to move the union scheme forward, and Mr. Galt found

his opportunity first as a diplomat in arranging the coalition and

afterwards as a Canadian delegate to the Charlottetown Conference. He

was one of the Ministers to sail on the Queen Victoria, the ship of

destiny freighted with the inarticulated hopes of a nation yet to be.

Galt’s unique powers as an exponent of finance were never used to better

advantage than here. At that momentous gathering, called to discuss “the

reunion of the Maritime Provinces,” as Tupper had aptly phrased it, Galt

made an impressive address.

“The financial position of Canada,” says John Hamilton Gray, the

delegate-historian of the Confederation Conference, of Galt’s speech,

“was contrasted with the other Provinces, their several sources of

wealth, their comparative increases, the detrimental way in which their

conflicting tariffs operated to each other’s disadvantage, the expansion

of their commerce, the expansion of their manufactures, and the

development of the various internal resources that would be fostered by

a further increase of trade and a greater unity of interest, were

pointed out with great power by Mr. Galt in a speech of three hours.

Statistics were piled upon statistics, confirming his various positions

and producing a marked effect upon the convention. It might almost be

said of him on this occasion as was once said of Pope, though speaking

of figures in a different sense:

“‘He lisped in numbers—for the numbers came.’”

From now on, for the next two years, Galt was a virile leader in

promoting the cause of union. At the Quebec Conference he played an

important part in finally adjusting the financial relations of the

Provinces under the union scheme, a point which at one time brought

deadlock and almost wrecked the convention. At a banquet during the

Quebec Conference Galt prophesied great prosperity as a result of

Confederation, pointing to the enormous free trade area of the United

States as an object lesson in promoting commerce.

At Sherbrooke, on November 23 of the same year, in an important speech,

Galt defended the union of 1841 as far as it had gone, and held that the

concession of representation by population would be attended by a

dangerous agitation. The Provinces of British North America, if united,

he said, would form a power on the northern half of the continent “which

would be able to make itself respected, and which he trusted would

furnish hereafter happy and prosperous homes to many millions of the

industrial classes from Europe now struggling for existence.”

“By a union with the Maritime Provinces,” he added, “we should be able

to strike a blow on sea, and, like the glorious old mother country,

carry our flag in triumph over the waters of the great ocean.” If Galt

meant the creation of a Canadian navy or a Canadian wing of the British

navy, history has shown him too optimistic on that one point. In this

speech Galt also upheld the rights of the minority in education in all

Provinces, rights which he said must be protected in the new

constitution.

Mr. Galt made one of the important speeches during the Confederation

debates in 1865, when in his thorough manner he discussed the economics

of the situation. He quoted the trade returns of the various Provinces

in 1863 as follows: Total exports and imports— Canada, $87,795,000 or

$35 per head; New Brunswick, $16,729,680, or $66 per head; Nova Scotia,

$18,622,359, or $56 per head; Prince Edward Island, $3,055,568 or $37

per head; Newfoundland $11,245,032 or $86 per head; a total of

$137,447,567. These figures compared with the total trade of the

Dominion of Canada of over two billion dollars in 1916—much of it, it is

true, a forced development from the war—are a flashlight on the success

which has followed Confederation, at least in that direction. Galt

foresaw much of this growth and in a passage in this speech gave rein to

his imagination:

“Possessing as we do in the far western part of Canada perhaps the most

fertile wheat-growing tracts on this continent, in central and eastern

Canada facilities for manufacturing such as cannot anywhere be

surpassed, and in the eastern or Maritime Provinces an abundance of that

most useful of all minerals, coal, as well as the most magnificent and

valuable fisheries in the world; extending as this country does over two

thousand miles, traversed by the finest navigable river in the world, we

might well look forward to our future with hopeful anticipation of

seeing the realization not merely of what we have hitherto thought would

be the commerce of Canada, great as that might become, but to the

possession of Atlantic ports which we should help to build to a position

equal to that of the chief cities of the American continent.”

The spade work for Confederation in Canada had now been done, though

much remained as yet to reconcile Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Galt

had his part in the mission to London in 1865. All was then smooth, but

in August, 1866, he startled the country by resigning as Finance

Minister on the determination of the Government not to proceed with the

Lower Canada education bill. This bill was promoted by the Protestant

minority of Lower Canada, and the Roman Catholic majority would not

permit it to pass unless a similar bill with reference to the Roman

Catholic minority in Upper Canada was also enacted. John A. Macdonald,

in voicing the Government’s position, said the policy advocated for the

minorities would give the Maritime Provinces an unfortunate spectacle of

two Houses divided against themselves. “Instead of a double majority,”

he said, “we should have a double minority.”

Notwithstanding his resignation from the Cabinet, Galt’s abilities were

requisitioned for the final stages of the Confederation bill, and he

accompanied the Ministerial delegation to England in the fall of 1866 to

draft the B. N, A. Act. He entered the first Confederation Cabinet as

Minister of Finance and, like Cartier, revolted at the proffered C. B.

as insufficient recognition for his services, and was subsequently, in

1869, made a K. C. M. G. His tractability was of short duration. In

November, 1867, he resigned from the Cabinet, and there has always been

an air of mystery as to the cause. Sir John Rose, who succeeded him,

told friends that he found the business of the Department in ragged

shape, so far as preparing for the next Budget was concerned, a fact

which might indicate irresolution for some time. The correspondence

subsequently made public shows that he resented the refusal of his

colleagues to go to the rescue of the Commercial Bank, in which he was

heavily interested. His letter of November 3 to Sir John Macdonald

affirms his decision to “withdraw from official life until at least I

have had the opportunity of putting my affairs in something like

order.”*

The portfolio of Finance was again offered him in 1869 if he would

renounce his views in favor of the independence of Canada, but he

declined. Galt then went into opposition to Sir John Macdonald, who

reciprocated the opposition with the utmost heartiness. Writing to Sir

John Rose on February 23, 1870, Sir John said:

“Galt has come out, I am glad to say, formally in opposition and

relieved me of the difficulty connected with him. . . . He is now

finally dead as a Canadian politician.”

Galt was, however, far from dead and buried. In 1876, in a letter to

Senator James Ferrier, he criticized Macdonald for his connection with

the Pacific Scandal. The Conservative chieftain, then in defeat and

dejection, expressed the anger of a man wounded in the house of a

friend, and responded half-heartedly to approaches for a renewal of

friendship. A year later the Mackenzie Government used Galt’s diplomacy

with good result on the Fisheries Commission at Halifax, and in 1880 Sir

John Macdonald made him the first Canadian High Commissioner to Great

Britain, declaring him to be “the most available man for the position.”

To Galt, however, the post was a disappointment, as he felt he was

little more than an emigration agent. He resigned in 1883. In a speech

in London on January 25,1881, Galt admonished the old country for not

entering upon a policy of settling her people in the Dominions. His

words have a strange flavor of the year 1917.

“I speak now,” he said, “not of Canada alone, but of her sister colonies

as well, when I affirm that within the limits of the British Empire

everything required by civilized man can be produced as well as in the

whole of the rest of the world; while if facility of access be taken

into account Canada stands on more than an equal footing with her great

rival, the United States. . . Canada is now doing her part in the effort

to colonize British North America, and it rests with the Government and

the people of England to do theirs.”

Galt’s last ten years of life were spent in comparative retirement,

interrupted by business investments in coal lands in western Canada. His

death in Montreal on September 19, 1893, from cancer qf the throat,

followed a long illness.

Sir Alexander Galt’s death drew praise from far and wide for his

services in shaping the young Canadian nation. He brought to the

councils of State a clear mind, an alert business judgment, and an

independent character. He left the memory of a sturdy, lovable man whose

services were generous and unselfish, and who was too big to be

controlled for sinister political purposes.

The Life and Times of Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt

By Oscar Douglas Skelton (1920) |