|

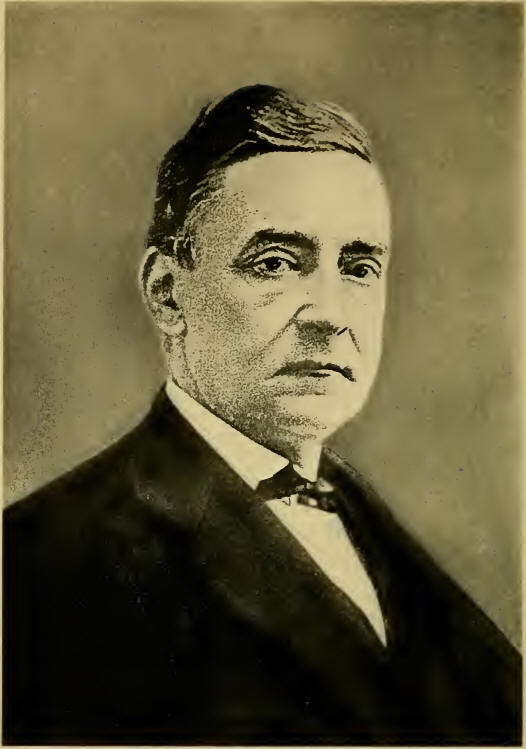

(1818-1891)

JUDGED by the sordid

standards of the spoilsman, the public life of Antoine Aime Dorion was a

failure; out of two decades of public life he held office for but a few

months. Judged by standards of honest duty, his life was successful; he

held his ideals and remained an unblemished public servant. Dorion was

the ally of George Brown, as Cartier was the ally of John A. Macdonald.

Dorion and Cartier represented the agelong fight between progress and

reaction; but it was Cartier’s fortune to win and achieve, Dorion’s to

lose and oppose. While history justifies Cartier’s advocacy of

Confederation, it cannot wholly condemn the conscientious objections of

Dorion. Cartier was an impetuous optimist, who saw unlimited progress in

union. Dorion was an honest pessimist, who believed a union of all the

Provinces too great an undertaking. Cartier was converted to union in

1858 by the arguments of Galt. Dorion favored a federation of the two

Canadas as early as 1856. Cartier was backed by the priesthood and lured

by national expansion. Dorion by prophesying the domination of the

British province seriously threatened the Confederation cause.

Dorion’s steadfast opposition led to a pathetic breach with George

Brown. They had been deskmates in the Assembly, their ideas were

similarly radical, they consulted on all things and agreed on most

things.

They joined in forming the Brown-Dorion Government, of a few days’

duration, in 1858, but they parted on the coalition of 1864. Brown threw

away his political advantages to join his foes and aid Confederation.

Dorion and Holton* opposed the coalition and declared it was a mere

scheme by Macdonald to hold office. This beautiful friendship between

Brown and Dorion had stood the tension of interprovincial warfare, when

Brown abused the Lower Canadians and Dorion championed his own people,

but it split on the issue of union, to which Dorion’s opposition was in

detail rather than in principle. On Brown’s resignation from the

Cabinet, a year later, the old relations were resumed, and held until

Brown’s death in 1880.

Antoine Dorion came of a noted family of French-Canadian public men, his

father, P. A. Dorion, his grandfather, an uncle and a brother all being

at some time members of the Assembly or Legislative Council. He was born

in the parish of St. Anne de la Perade, in the County of Champlain, on

January 17, 1818. After local schooling, his father, a general merchant,

sent him to Nicolet College, and he was called to the Bar in 1842. He

was soon conspicuous in law in Montreal, and showed political capacity,

though he was not elected to Parliament until 1854. Papineau, then a

veteran and bearing the tarnish of the Rebellion of 1837, was still

powerful, and round him gathered a group of energetic young men, who in

1850 formed the Parti Rouge, asserting one of the most radical platforms

ever presented in the country. The French revolution of 1848 had just

inflamed the youth of Europe, and the young bloods of the Parti Rouge

considered themselves worthy of the men of Paris. Their newspaper,

L’Avenir, advocated universal suffrage, an elective judiciary, abolition

of property qualifications for members of the Legislature, abolition of

State religion, and even annexation to the United States. “In former

ages,” said UAvenir, “Christianity, sciences, arts and printing were

given to the nations to civilize them; now popular education, commerce

and universal suffrage will make them free.”

Before this onslaught, which had its counterpart in Upper Canada in the

“Clear Grits”- of the day, Lafon-taine retired from public life in 1851,

despondent at the division in his party. The man who had accomplished

responsible government three years before was now too conservative! In

1854 Papineau’s tempestuous public career ended, and with his retirement

A. A. Dorion became the leader of the Rouges. The new party reached its

zenith at the elections of that year, when nineteen Rouges were returned

to the Assembly. The majority were young men of earnestness and ability,

and their fault was in their youth. Time modified their views, and

Dorion’s radicalism was the foundation of the future Liberal party of

Quebec.

Dorion entered Parliament equipped for the large part he was to play in

public life. He was already distinguished at the Bar, his education was

thorough, and his manner courtly and polished. He declined to join in

the coalition of 1854, and for the next four years was a destructive

critic of the Administration. Cartier offered him the post of Provincial

Secretary in 1857, but he declined. In the elections of December and

January following, the Rouges paid the penalty for their alliance with

the “Clear Grits,” and their ranks were sadly thinned. Dorion was

returned, and in the following August he joined in the formation of the

Brown-Dorion Government after the fall of the Macdonald-Cartier Cabinet.

The new Government’s resignation after two days followed a

misunderstanding with the Governor, Sir Edmund Head, who refused a

dissolution.

The importance of this Ministry lies in the understanding reached by

Brown and Dorion on future policies. The French-Canadian leader agreed

“that the principle of representation by population was sound, but said

that the French-Canadian people feared the consequences of Upper

Canadian preponderance, feared that the peculiar institutions of French

Canada would be swept away. He therefore thought that representation by

population must be accomplished by constitutional checks and safeguards.

Brown and Dorion parted in the belief that this could be arranged. They

believed also that they could agree upon an educational policy in which

religious instruction could be given without the evils of separation.”

The agreement was destined to failure through the return of the

Cartier-Macdonald Government to office by the “Double Shuffle.” Dorion

was defeated in 1861, Sicotte becoming Rouge leader, but returned the

next year and held office as Provincial Secretary for a few months in

the Sandfield Macdonald-Sicotte Government. Dissatisfaction with the

Government’s policy on the Intercolonial Railway led to his resignation

in January, 1863, but he was again in office for a few months as

Attorney-General East in the reconstructed Sandfield Macdonald-Dorion

Cabinet. This ended Dorion’s Cabinet service, except for six months in

the Mackenzie Government a decade later. His intervening years were

marked by the many duties of an Opposition critic armed with a rapier,

and never using the coarser weapons of an untrained mind.

The Confederation battle in Lower Canada was marked by party, racial and

personal considerations. It was the heyday of George Etienne Cartier,

and his dashing courage attempted to carry all before it. Dorion was one

of a group of exceedingly able men who opposed him. Dorion’s position

bears some resemblance to that of Joseph Howe in Nova Scotia. Like Howe,

he had been an early advocate of a form of federation. As early as 1856

he had moved this resolution:

“That a committee be appointed to inquire into the means that should be

adopted to form a new political and legislative organization of the

heretofore Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, either by the

establishment of their former territorial divisions or by a division of

each Province, so as to form a federation having a federal government

and a local legislature for each one of the new Provinces, and to

deliberate as to the course which should be adopted to regulate the

affairs of United Canada in a manner which would be equitable to the

different sections of the Province.”

Thus Dorion admitted the unsatisfactory conditions which then existed.

Brown, his deskmate, was preaching the failure of the union, and in 1859

the Upper Canada Reformers called for its repeal. The union, which began

in 1841 with equal representation, though Lower Canada then had 625,000

people to Upper Canada’s 455,000, was an increasing annoyance with

890,000 in Lower Canada and 952,000 in Upper Canada by 1851. Lower

Canadians could point to their own generosity in granting equal

representation, but the disparity grew so rapidly as to accelerate the

discontent beyond the Ottawa.

It might have been expected that Dorion would have followed the gleam

and taken the larger view. In 1859 he saw only two logical alternatives:

dissolution of the union or federation, on the one hand, and

representation by population on the other. Two years later he had

admitted the time might come when a federation of all the Provinces

might be necessary. But when the great test came he broke with Brown,

fought Cartier and the Church—which in turn bitterly opposed the

Rouges—and assumed the role of a Faint-heart.

Before the Quebec Conference was a month over, Dorion was on record as

an opponent of the scheme and issued a lengthy manifesto to his

constituents in Hoche-laga. “It has always appeared to me,” he said,

“that the present circumstances of the several Provinces do not render

such a union desirable, and that we might by a treaty of commerce and

reciprocity assure to each Province all the advantages which might be

procurable or derived from a union. I do not see anything in the scheme

of federation to induce me to alter my opinion.”

Dorion’s speech in the Confederation debates, on February 16, 1865, was

one of the ablest contributions from the opponents of union. Some of his

prophecies of evil, such as his strictures on the nominated Senate, have

been justified; others were unfounded and quickly forgotten. True to his

early advocacy of elective public servants, Dorion opposed the

nomination of Governor-General, local Governors, Senators and

Legislative Councillors as portending “the most illiberal constitution

ever heard of in any country where constitutional government prevails.”

As a consistent opponent of the Intercolonial Railway, he pictured the

Grand Trunk as backing the new project of Confederation in order to

secure the building of the new line to the eastern Provinces. That

railway, it is quite true, has brought deficits and patronage evils, but

its value as a backbone of national connection and sentiment cannot be

denied. Dorion, like Oliver Mowat in Upper Canada, was strong for

provincial rights, and opposed the veto power retained by the central

government.

“Do you not see,” he said, “that it is quite possible for a majority in

a local government to be opposed to the general government; and in such

a case the minority would call upon the general government to disallow

the laws enacted by the majority? . . . What will be the result in such

a state of things but bitterness of feeling, strong political acrimony

and dangerous agitation?”

It is fair to say that, while the powers of the central government have

been restricted under court decisions, the value of a strong authority

has been generally conceded. Dorion declared he would not say he would

be opposed to Confederation for all time. Population might extend over

the wilderness between the Maritime Provinces and Canada, and commercial

intercourse might increase sufficiently to render Confederation

desirable. He denied that he had ever favored union of all the

Provinces, and declared he stood, as for years past, for a federation of

the two Canadas.

On one thing Dorion was firm, and that was the protection of the

interests of the people of Lower Canada, whom he saw threatened with a

legislative union. “The people of Lower Canada,” he said, picturing the

feared oppression of a minority, “are attached to their institutions in

a manner that defies any attempt to change them in that way. They will

not change their religious institutions, their laws and their language

for any consideration whatever. A million of inhabitants may seem a

small affair to the mind of a philosopher who sits down to write out a

constitution! He may think it would be better that there should be but

one religion, one language, and one system of laws, and he goes to work

to frame institutions that will bring all to that desirable state; but I

can tell honorable gentlemen that the history of every country goes to

show that not even by the power of the sword can such changes be

accomplished.”

Dorion’s pessimistic view reached its climax in his conclusion:

“I will simply content myself with saying that for these reasons, which

I have so imperfectly exposed, I strongly fear it would be a dark day

for Canada when she adopted such a scheme as this. It would be one

marked in the history of this country as having had a most depressing

and crushing influence on the energies of the people in both Upper and

Lower Canada, for I consider it one of the worst schemes that could be

brought under the consideration of the House, and if it should be

adopted without the sanction of the people, the country would never

cease to regret it.”

Barely was the momentous debate in Quebec concluded before Dorion and

his Rouge associates were at work among the people. A score of

French-Canadian counties favored a plebiscite, and more than 20,000

persons signed petitions against final action without a popular vote.

Dorion, L. O. David, Mederic Lanctot and others spoke against the union

measure. Wilfrid Laurier, then a young lawyer of twenty-three, spoke at

St. Julie, in Montcalm County, in February, 1865, along with other

opponents, including the fiery Lanctot, then his law partner. Laurier’s

words are not recorded, except to say that he supported the other

speakers, and resolutions in support of Dorion’s policy were adopted.

So the battle went on, the Rouges meeting the people, but unable to make

headway against the combined Cartier and clerical influence, then

sweeping the Province.

Dorion and nineteen other members of the Assembly, including Holton and

Huntington, issued a final “Remonstrance” in October, 1866, addressed to

the Earl of Carnarvon. In this they asked, in moderate language, for the

submission of union to the people before it became effective. “We seek

delay,” they said, “not to frustrate the purposes of a majority of our

countrymen, but to prevent their being surprised, against their will or

without their consent, into a political change which, however obnoxious

and oppressive to them it might prove, cannot be reversed without such

an agitation as every well-wisher to his country must desire to avert.”

Such appeals to reason broke down before the forces united for union.

The final undoing of the opposition came through a characteristically

adroit move by Sir John A. Macdonald. In the summer of 1867 he chose as

the first Premier of Quebec, P. J. O. Chauveau, a fr end and former

follower of Papineau, but now a staunch upholder of Catholicism. With

Cartier at Ottawa and Chauveau at Quebec, the habitant was not alarmed

for his future.

Dorion was elected to the House of Commons in 1867 and continued, in the

reunited Liberal party, an alert critic of the new Administration. In

the first session he resumed his activity against the Intercolonial

Railway by moving—unsuccessfully, of course—that the route should not be

determined without the consent of Parliament. In 1873 he was associated

with Edward Blake as Liberal member of the Committee to probe the

Pacific Scandal, but they eventually refused to act in the capacity of a

commission as asked by the Government, when the Oaths Act had been

disallowed as ultra vires. When the Mackenzie Government came in on the

wave of anger aroused by the scandal, Dorion became Minister of Justice.

His few months of office at this time were marked by the passage of the

electoral law of 1874 and the Controverted Elections Act.

Dorion was now fifty-six years old, and twenty years in politics had

worn his body and absorbed his means. He was offered and accepted the

office of Chief Justice of Quebec, for which his legal abilities and his

just character eminently fitted him. Seventeen years of unswerving

devotion to duty on the Bench enhanced the respect and affection in

which he was held. At the end of May, 1891, while political strife

throughout Canada was hushed as citizens of all parties watched the

passing of Sir John A. Macdonald, Dorion was stricken with paralysis, in

the midst of his service, and died at his home in Montreal on the last

day of the month. The Conservative chieftain, who had been his

antagonist for so many years, followed in less than a week.

A polished gentleman of another day passed in Dorion. “A man of

exquisite courtesy of manners,” Sir Wilfrid Laurier wrote of him, “he

yet always was somewhat distant. He never had recourse to the easy

method of winning popularity by promiscuous familiarity. He never

pandered to the vulgar tastes, never deviated from the path which seemed

to him the path of truth. He never craved success for the sake of

success; he steadily struggled for the right as he saw the right. He met

defeat without weakness, and when success came, success found him

without exultation.”

Dorion’s actual accomplishment in legislation is slight; his noble and

serene character stands out with a white light in the murk of political

warfare.

“Canada has had few nobler servants than Antoine Dorion,” wrote J. S.

Willison in “Sir Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal Party.” “A man of

magnanimous spirit, of beautiful character, and of rare sagacity, he

fought through a long public career, in a bitter and factious time,

without a stain upon his shield, unsoured by reverses and untouched by

sordid bargainings for the spoils or the dignities of office.” |