|

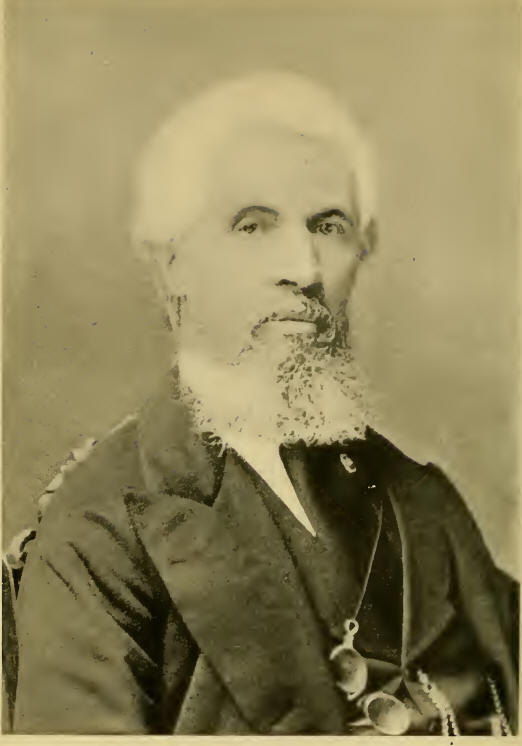

(1811-1881)

AN under-sized, slim,

wiry man, with a nervous, energetic air, a lawyer whom D’Arcy McGee

called a “hair-splitter,”—this was Christopher Dunkin, who introduced

temperance legislation into the Province of Canada, and who delivered

the ablest speech against Confederation in the memorable debates of

1865. On temperance the world in general, and Canada in particular, has

moved far beyond him. On Confederation his doleful prophecies have not

been realized, though events have justified some of his criticisms. It

is a curious fact that A. A. Dorion, the French Catholic, feared that

Confederation would overwhelm the French race in the Dominion, while

Dunkin, the Protestant, was alarmed, in turn, for the welfare of his own

race under the local government of Quebec. Time has shown that no

Canadian Government could live without liberal support from Quebec,

while the chief complaint of Quebec Protestants is that the French are

crowding them out by increase of population.

Christopher Dunkin was the lawyer in politics. He was voluminous in

speech, drew fine distinctions, often not obvious to others, and he was

totally lacking in eloquence. He was serious, earnest, and scholarly,

and, as Sir William Dawson has said, would have made a good college

president. His professional life was successful, and many a wealthy

client found his way to the office of Bethune & Dunkin in Little St.

Janies Street in Montreal, a thoroughfare so narrow that dexterous young

men might almost leap across it. Montreal in those days was still

largely British and Protestant, a survival of early fur trading days, as

contrasted with the overwhelming.French element of the present time.

Dunkin took up law late in life, being called to the Bar in 1846, at the

age of 35, but except for four years of public office, from 1867 to

1871, he gave the rest of his years to that profession, the last ten

being spent on the Bench.

Dunkin was born in London, England, on September 24, 1811, and after an

education at London and Glasgow Universities he migrated to the United

States, where he taught Greek for a time at Harvard University. He came

to Lower Canada a little later and edited The Morning Chronicle in

Montreal for a year, in 1837-8. About this time he came under the notice

of the Earl of Durham, and was appointed Secretary of his Education

Commission, and later was Secretary of the Post Office Commission. On

the adoption of Union in 1841 he was appointed Assistant Secretary for

Lower Canada, holding the post until elected to the Assembly in 1847.

These varied experiences, together with his legal training, gave Dunkin

an education for public life. He sat for Drummond and Arthabaska until

1861, and for Brome from 1862 until his retirement. Yielding to a clamor

for a resident member, he moved to Knowlton in the middle ’sixties, and

with his wife, formerly Miss Mary Barber of Montreal, a superior woman,

took part in welfare work for the benefit of immigrant girls.

His party affiliations were Conservative, but on the issue of

Confederation, as in other matters, he acted with independence.

One of Dunkin’s historic legal cases was his argument on the seigniorial

tenure question. In 1853, when L. T. Drummond introduced a Government

measure proposing to reduce such of the lands as were held to be

exorbitant, and to obtain judicial decisions as to their legality,

Dunkin appeared at the bar of the House, and for an entire evening

presented with great skill the question from the seigniors’ point of

view. The bill was finally passed by the Assembly, but rejected by the

Legislative Council.

Dunkin’s great speech against Confederation was made during the lengthy

debate at Quebec in the winter of 1865. Though he apologized for being

physically unfitted for the task before him, he occupied the evening of

February 27 and the entire afternoon and evening until almost midnight

of the next day. He began with a well sustained prepared utterance, but,

as he proceeded, the interruptions of other members, chiefly his

opponent Cartier, though good-natured, broke its continuity and resulted

in a certain diffuseness. Dunkin’s speech was not eloquent, but it is

regarded as the most elaborate and effective argument given against

union. He said he believed he was opposed to powerful odds, and that

there was a feeling of hurry and impatience in the House. He had always

been a unionist in the strict and largest sense of the term, he said. “I

desire to perpetuate the union between Upper and Lower Canada. I desire

to see developed the largest union that can possibly be developed—I care

not by what name you call it—between all the colonies, provinces and

dependencies of the British Crown.”

In this sentiment Dunkin resembled Howe of Nova Scotia, another Imperial

federationist. Half a century was to pass without the idea being

advanced in any formal way, though the outbreak of war in 1914 revealed

an Imperial unity of feeling that no mere federation of parliaments

could have developed.

Dunkin said the Confederation scheme amounted practically to a division

of Upper and Lower Canada, and on that account he was irrevocably

opposed to it. He even saw in it a tendency to a not distant division of

those Provinces from the British Empire. He favored rather a slow change

and growth as in the physical world. There had been no demand for

Confederation; the idea had no place in the public mind. Representations

had been made to the Imperial Government in 1858, and when the

despatches were laid on the table in 1859 “nobody asked a question about

them.”

In 1864, Dunkin recalled, George Brown had secured a committee to

consider constitutional changes. “That honorable gentleman did a very

clever thing in embodying in his motion extracts from the unfortunate

defunct despatch of Messrs. Cartier, Galt, and Ross.” “It was a

fortunate despatch,” Cartier broke in,— “unfortunate for you but

fortunate for us.”

“It is an old proverb that says, ‘He laughs well who laughs last,’ ”

Dunkin replied.

“I expect to laugh the last,” answered Cartier.

“We have yet to see,” Dunkin went on, “in the first place, whether the

thing is done, and then, if it is done, if it succeeds.”

“If ’twere done, ’twere well it were done quickly,” was the ready sally

from D’Arcy McGee.

Dunkin admitted that he had voted and spoken for Brown’s committee, and

had sat on it, but claimed the Confederation part of their report had

been opposed by John A. Macdonald himself and had been inserted

unexpectedly at the last moment.

Analyzing the scheme in greater detail, Dunkin said it promised

everything for everybody, and yet the terms were ambiguous,

unsubstantial, and unreal. They were called upon to admit that the work

of 33 gentlemen done in seventeen days was much better work than that of

the framers of the United States constitution, or even the constitution

of the motherland. The House of Commons was to follow largely the

American House of Representatives, which he considered the wrong model.

He regarded the American Senate as “the ablest deliberative body \ the

world has ever known,” but the method of choosing the Canadian Upper

House would make for a lower quality of men. The duty of advising and

aiding the head of the government in the discharge of executive

functions fell wholly upon the executive council, while in the United

States the Senate had large executive functions.

“Without responsibility for their advice,” said Cartier, interrupting.

“We have responsibility, and in that respect our system is better.”

Dunkin then prophesied there would be difficulty in giving all classes

and sections of the country representation in the Cabinet, a prophecy

which was subsequently justified by Sir John A. Macdonald’s experience

in forming his Cabinet in 1867.

“It will be none too easy a task,” Dunkin said, “to form an executive

council with its three members for Lower Canada, and satisfy the

somewhat pressing exigencies of her creeds and races.”

“Hear, hear,” said Cartier.

“The Honorable Attorney-General East probably thinks he will be able to

do it,” said Dunkin.

“I have no doubt I can,” responded the man of action, with his usual

confidence.

Lack of uniformity, Dunkin said, would characterize the constitutions

and legislation of the various provinces. The federal right of

disallowance would result in clashes with the local governments. Dunkin

expressed fear that lieutenant-governors would be appointed whose past

political career might render them unwelcome to the majority in the

provinces.

Experience has not found this a substantial grievance, as

lieutenant-governors are a social rather than an executive force.

Though the champion of the Protestants of Quebec, Dunkin sought to

awaken the fears of the French. “The moment,” he said, “you tell Lower

Canada that the large sounding powers of your general government are

going to be handed over to a British American majority, decidedly not of

the race and faith of her majority, that moment you wake up the old

jealousies and hostility in their strongest form. The French, he

continued, “will find themselves a minority in the general legislature,

and their powers in the general government will depend upon their power

within their own province, and over their provincial delegations in the

federal Parliament. They will themselves be compelled to be practically

aggressive to secure and retain that power.”

The financial outlook caused anxiety for Mr. Dunkin. Local governments

would depend largely on the general government for revenue. He pictured

provincial candidates boasting to their electorate of the increases in

subsidies they had secured from the Dominion, and added: “I am afraid

the provincial constituencies, legislatures, and executives will all

show a most calf-like appetite for the milk of this most magnificent

government cow.”

Dunkin had no love for the Intercolonial nor for the idea of Western

expansion. He saw no great commercial or military advantages in the

former, and if it had political value the mother country should aid in

its construction. Expansion could only be coupled with expenditures they

had not yet dreamed of. One of his last arguments was an appeal to local

pride:

“The Federal Government of the United States takes its place in the

great family of nations of the world; but what place in that family are

we to occupy? Simply none. The Imperial Government will be the head of

the Empire as much as ever, and will alone have to attend to all foreign

relations and national matters; while we shall be nothing more than we

are now. Half a dozen colonies federated are but a federated colony

after all. Instead of being so many separate provinces with workable

institutions, we are to be one province, most cumbrously

organized—nothing more.”

Why not, he concluded, go on with the institutions they had? The one

thing needed was “the exercise by our public men and by our people of

that amount of discretion, good temper, and forbearance which sees

something larger and higher in public life than mere party struggles

and-cries without end; of that political sagacity or capacity, call it

what you will, with which they will surely find the institutions they

have to be quite good enough for them to use and quietly make better,

without which they will as surely find any that may anyhow be given them

to be quite as bad for them to fight over and make worse.”

Though Dunkin had argued almost exhaustively against Confederation, when

it became apparent that no action on his part could achieve its defeat

he declared, in 1866, his determination to aid in making it as

beneficial as possible. He assisted in forming the preparatory

legislation and championed the educational rights of the minorities in

both Upper and Lower Canada. When the first Quebec Cabinet was being

formed in 1867 by Mr. Cauchon, Dunkin declined a portfolio on the ground

that Cauchon had been unjust to the Protestants of Quebec in opposing

Langevin’sf bill, giving them control of their own schools. As Dunkin’s

decision was followed by other Protestants’ refusal, Cauchon could not

form a Cabinet. Chauveau was called on, and Dunkin entered his

Administration as Treasurer. Two years later he joined the Dominion

Cabinet as Minister of Agriculture and Statistics, and in October, 1871,

was made a puisne Judge of the Superior Court of Quebec.

Christopher Dunkin’s name is inseparably connected with temperance in

Canada. He was a religious man with a strong sense of public duty, and

the Temperance Act which bears his name was a pioneer measure of reform.

When taunted with the statement that no county would carry it, he said

he would resign if his own county of Brome would not accept it. It was

adopted and remained in force during his lifetime.

When Dunkin introduced his temperance bill in 1864 he naturally did not

attract enthusiastic notice. The country was honeycombed with taverns

and distilleries, and no social gathering was considered complete

without the liquor that then had few enemies. There had been agitations

in the Maritime Provinces and in the United States against the “demon

rum,” but the permissive legislation known in history as the Dunkin Act

was the first measure of its kind in Canada. Its title in the Statutes

of 1864 is: “An Act to amend the laws in force respecting the sale of

intoxicating liquors and the issue of licenses therefor, and otherwise

for repression of abuses resulting from such sale.” It was the

forerunner of the Scott Act and the local option laws of later days, and

for some years a sprinkling of municipalities became comparatively “dry”

under its provisions.

Mr. Dunkin’s explanation of the bill attracted almost no notice in the

newspapers of the day, a fact which illustrates the paucity of interest

in the subject. The Globe's despatch from Quebec on May 12 said:

“Mr. Dunkin, in moving the House into committee on his Temperance bill,

explained its provisions clause by clause, speaking upwards of two

hours, and afterwards repeated some of his explanations in French, which

language he speaks with much fluency and correctness.”

On the 18th the House spent the afternoon and evening in committee on

the bill, made some amendments and reported it, thus giving a start they

doubtless little appreciated at the time to a chain of legislation which

has since covered the greater part of Canada in much more drastic form.

In the serenity of age Judge Dunkin passed his ten years on the Bench,

going about among his own people in a dignified and altogether suitable

profession. His circuit of Bedford and Beauharnois gave him contact with

the two races whose language he had mastered and whose contrasting

peculiarities he understood. He was a painstaking and earnest Judge,

holding the respect of lawyers and enjoying the confidence of litigants.

He encouraged agriculture and was an inspiration to the progressive

farmers of that stock-raising region.

Judge Dunkin passed away at his home at Knowlton on January 6, 1881,

having reached his three score and ten, leaving a reputation for

singular uprightness and devotion to duty. |