|

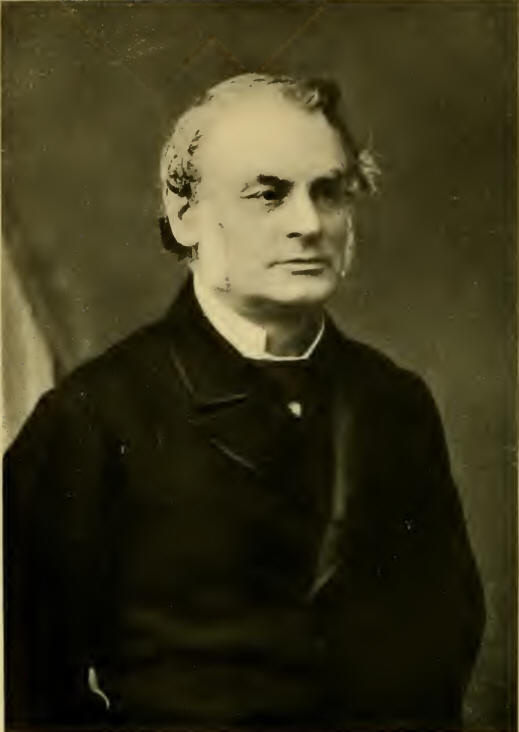

(1818-1896)

WHILE Upper Canada was

all but unanimous for » » Confederation, and in Lower Canada Cartier was

rapidly conquering opposition, down in the Maritime Provinces there was

antagonism which almost paralyzed the whole movement. The burden of the

battle for union in New Brunswick fell largely on Samuel Leonard Tilley,

once an apothecary’s apprentice, later Premier of his Province, and

destined to stand high in the councils of the new, wide Dominion. For

his trying task, Tilley brought qualities of no ordinary strength. He

was energetic, kindly, honest, gentlemanly, with scarcely an enemy in

the world. He was a fluent, forceful speaker, with an attractive

presence and a penetrating political judgment. He was a Puritan in

principle and the first statesman in British North America to introduce

a prohibitory liquor bill.

Tilley’s strong principles did not lessen his friends, for he had a

saving sense of humor. When he was Finance Minister at Ottawa he carried

his temperance practice into effect at his official dinners. But on one

occasion, as the plum pudding was brought in, covered with a rich blue

blaze, John Henry Pope, of Compton, one of the members present, said in

a stage whisper:

“’Pon my word, I never saw ginger ale burn like that.”

Tilley joined in the roar of laughter that followed.

Isolated, unprotected and in need of liberal development, New Brunswick

early felt the need of union. In 1853 when the first sod was turned for

the railway from St. John to Shediac, the directors of the new line,

addressing Sir Edmund Head, then Governor, expressed the hope that the

British Provinces should become “a powerful and united portion of the

British Empire.” Sir Edmund Head endorsed the sentiment and hoped the

people of Canada and the Maritime Provinces would speedily realize that

their interests were identical. The desire for railways was an abiding

ambition for the Province, and the Intercolonial was one

will-o’-the-wisp that hastened consideration of Confederation.

Tilley had been an approving listener in 1860 when Dr. Charles Tupper,

lecturing in St. John, advocated a union of British North America. Two

years later he attended the conference at Quebec regarding the

Intercolonial Railway, and visited Upper Canada, when delegates

informally urged a union of the Provinces. The Trent Affair, and the

despatch to Canada of troops who had to be sent overland to Quebec on

sleds in winter, enforced the need of a railway when the delegates from

the various Provinces went later to England to seek Imperial aid.

Despite the urgency of the plea of Tilley and Howe, terms were not

agreed upon, and the project was delayed indefinitely. It became,

however, a live issue at the Quebec Conference in 1864. Tilley, who had

joined with Tupper in organizing the Charlottetown Conference for a

Maritime union, was outspoken at Quebec on the railway question.

“The delegates from the Lower Provinces were not seeking this union,” he

said at the banquet. “They had assembled at Charlottetown in order to

see whether they could not extend their family relations, and then

Canada intervened and the consideration of the larger question was the

result.” Alluding to the Intercolonial Railway project he said: “We

won’t have this union unless you give us the railway. It was utterly

impossible we could hare either a political or commercial union without

it.”

Tilley’s genius for finance was a factor in the formation of the

resolutions at Quebec, and his attractive personality radiated good-will

and won friends everywhere during the visit to Upper Canada. But there

was an awakening when he returned to his own Province. He was not long

at home before mischievous criticisms appeared. The secrecy of the

Conference gave rise to many of the early misconceptions. A few days

after the Charlottetown Conference closed the St. John Globe said:

“We should not be surprised to find that the federation meeting at

Charlottetown will result in a ‘great fizzle.’ The doings of any

convention or association that meets nowadays with closed doors rarely

amount to anything in so far as they affect the public. The members of

the convention made a great mistake in not inviting the press to attend

their deliberations. They could have had very little to say that the

public ought not to hear.”

Before November had ended it was clear that union was in for a stiff

struggle in the Province. A formidable opposition was already growing

up, and a number of the ablest papers in St. John were trying to turn

the whole thing into ridicule. Tilley was already on the defence with a

declaration that he would submit the question to the people. In a speech

he pointed to the enlarged market the manufacturers of New Brunswick

would have under union. He referred good-humoredly at St. John to the

aspersions cast on Upper Canadian politicians, and said one would

imagine that all at once the politicians of New Brunswick had become

wonderfully pure and patriotic. He analyzed the financial aspects of the

agreement, and declared their revenue under union would be equal to what

they would derive from an increase of 200,000 in population under the

old conditions. He was confident that Upper Canada could not carry out

schemes for her own aggrandizement, for her 82 representatives would be

opposed in such a case by 65 from Lower Canada and 47 from the Lower

Provinces.

Nor were dangers from without forgotten by Mr. Tilley. He said he had

nothing but the most kindly feelings towards the American people. “It

was plain, however, that the English public, as well as the British

Government, have felt for some time that our position with reference to

the United States is not as satisfactory as it was in times past.” The

low values of colonial securities also reflected the feeling of

uncertainty of British capitalists with reference to the future destiny

of British America, while Lord Stanley had declared that Canada was the

most indefensible country in the world.

Hostility to the union scheme increased, fanned by resourceful opponents

who did not want their own sphere of officialdom eclipsed. Early in

March, 1865, the crash occurred. While the Confederation debate was in

full swing at Quebec, the message came one day that Tilley’s

Confederation Government, in the first of the Provinces affected to

consult the people, had been defeated, having carried only 6 out of 41

seats. Unionists were staggered and anti-unionists took hope that they

might yet overthrow the scheme then being forced through three

legislatures. The alarm which had prevailed in the Maritime Provinces

took on a more acrid form, and broadsides of abuse and misrepresentation

were fired on the union cause. New Brunswick was afire with excitement

and the country was overrun with pamphleteers and propagandists. The

bogey of direct taxation was held before the people and gained much

headway before the true nature of the resolutions could be presented. As

in Nova Scotia, the electors were told that they had been sold to the

Canadians for 80 cents per head, a reference, of course, to the subsidy

of that amount which the Dominion would pay to the Provinces. It might

have been said with as much truth that the Canadians had similarly been

sold to New Brunswick.

As in the other small Provinces, the cause of union met obstacles

inherent to the circumstances. The Legislature had authorized a

conference on Maritime union; a larger union was proposed without

consulting the electorate. Mr. Tilley had doubtless relied on his

eloquence and power to carry a scheme which the people did not

understand, and which appeared to be born of the political necessities

of Canada. The Province would have additional taxation, the opponents

said, and its political independence would be destroyed.

It was Tilley’s task to dissolve this vapor of ignorance and suspicion.

This he did by a campaign of energy and persistence, covering almost

every part of the Province. He was now a private citizen, he and all his

colleagues having been defeated in the March elections. He was in the

prime of manhood, his figure was attractive, his manner impressive and

his voice convincing to a people misled by agitators and ready to learn.

“I will make a house-to-house canvass of the Province,” he declared, and

he almost redeemed his threat. He appealed to the patriotism of the

people as he went from county to county, telling of the desire of the

motherland that union should be adopted. “Are you afraid?” he thundered,

with his organ-like chest, to a hostile St. John audience, as he entered

on the great campaign.

At this time the part of Arthur Hamilton Gordon (afterwards Lord

Stranmore and uncle of the Earl of Aberdeen, recently Governor-General

of Canada), Governor of New Brunswick, became a matter of importance.

Gordon had opposed Confederation, but a visit to England gave him new

light. Not long after the new Government of Albert J. Smith took office

in 1865, the Colonial Secretary wrote this advice to Gordon:

“You will impress the strong and deliberate opinion of her Majesty’s

Government that it is an object much to be desired that all the British

North American colonies should agree to unite in one government.”

A series of events then promoted a revulsion of feeling. Dissension

sprang up in the Smith-Hatheway Cabinet. The Legislative Council, led by

Peter Mitchell, in reply to the Speech from the Throne, endorsed union,

and Governor Gordon accepted this Address without consulting his

advisers. The Cabinet had no course but to resign, their resolution

being fortified by a threatened Fenian invasion and by defeat in an

important by-election.

Governor Gordon, whose conduct has been criticized as contrary to the

principles of responsible government, was now a firm friend of union and

did not hesitate to stretch his powers to aid the cause. Lengthy

correspondence took place between him and Premier A. J. Smith, in the

course of which, writing on April 12, 1866, Gordon said:

“He has no doubt as to the course which it is his duty to pursue in

obedience to his Sovereign’s commands and in the interests of the people

of British North America. His Excellency may be in error, but he

believes that a vast change has already taken place in the opinions held

on the subject in New Brunswick. He fully anticipates that the House of

Assembly will yet return a response to the communication made to them

not less favorable to the principle of union than that given by the

Upper House, and in any event he relies with confidence on the desire of

a great majority of the people of the Province to aid in building up a

powerful and prosperous nation under the sovereignty of the British

Crown. To this verdict his Excellency is perfectly ready to appeal.”

Tilley watched the constitutional struggle from the cool shades of

private life. He had been out of office for almost a year, but he was

far from being out of touch. He had formed a warm friendship with John

A. Macdonald, and on April 14, 1866, he wrote the Conservative leader an

extended account of the situation. He told of the break-up of the Smith

Government through the quarrel with Governor Gordon, and the appeal to

the country by Smith against the Governor’s conduct in answering the

Legislative Council’s Address in favor of union before he consulted with

his advisers.

“Had the break-up occurred in any other way,” he said, “we could without

doubt have put the Nova Scotia resolutions through this House and have a

majority to sustain the new Administration. As it is, I see nothing

before us but a general election, and we shall have to fight the

Opposition upon less favorable ground than we would if the simple

question of Confederation was at issue. The new Government will probably

be formed to-day, and I suppose I must go into it, and fight it out upon

the Confederate line.”

When the Smith Government resigned, the Governor called on Peter

Mitchell to form a Cabinet. Though Mitchell was an active unionist, he

advised the Governor that Tilley was the proper person to form an

administration, but the latter declined on the ground that he was not a

member of the Legislature. A Cabinet was then formed by Mitchell and R.

D. Wilmot, with Tilley as Provincial Secretary. The aggressive campaign

was continued, and the elections returned a large majority for

Confederation, the popular vote being 55,665 for union and 33,767

against. The battle for Confederation was completed by the adoption of

the Nova Scotia resolutions and the participation in the London

Conference to frame the bill. In this Tilley had a part, though the

delay in the arrival of the Canadian delegates was a trying incident.

Union was undoubtedly hastened in New Brunswick by the Fenian scare, and

was received in 1867 with more general approval than in Nova Scotia.

Tilley’s seventy-eight years of life epitomized the evolution of his

Province. At his birth New Brunswick had but 50,000 people, and it was

only 34 years since the Loyalist immigration reached the St. John

Valley. Wooden buildings were universal, people cooked and warmed

themselves by the open fireplace, homespun comprised everyone’s

clothing, and farm implements showed little advance on a thousand years

before. Tilley lived to see New Brunswick with over 300,000 inhabitants,

its prosperous settlements bordering the coasts and rivers, but its

interior still largely in possession of the lumberman and the moose. St.

John had become an important ocean port, and progress in manufacturing

kept pace with farming.

Tilley was born at Gagetown, a picturesque village on the St. John

River, on May 8, 1818. His ancestors were Loyalists, his

great-grandfather, Samuel Tilley, migrating from Long Island after the

American Revolution. His father, Thomas Morgan Tilley, was a house

joiner and builder. The youth attended the Gagetown Grammar School, and

at 13, with soaring ambition, went to St. John, where he became an

apprentice in Dr. Henry Cook’s drug store. A little later he entered the

store of William O. Smith, a shrewd business man of public spirit, from

whom he derived many political ideas. A smart, active and pleasing

youth, he attracted attention and soon joined the St. John Young Men’s

Debating Society, where, like many another public man, he had his first

and most helpful training in public speaking. In 1837 he enlisted in the

cause of temperance, and his prominence in this did much to draw him

into politics later. The next year he entered a drug partnership, and so

successful was his business life, in the growing port of St. John, that

when he retired in 1855 he was wealthy. Tilley’s life-long belief in

protection led him to support the candidature in 1849 of B. Ansley on a

high tariff platform. The following year he was a foremost member of the

New Brunswick Railway League, an organization formed as a protest

against the Legislature’s failure to assist railways, and having a line

from St. John to Shediac as its chief objective. In June of that year,

after a useful municipal career, Tilley was elected to the Legislature

during his absence from the city, and thereafter was never long free

from public duties. Responsible government had just been won under the

leadership of Lemuel A. Wilmot,* and a new era began.

It is unnecessary to trace the deviations of New Brunswick politics in

the early years of Tilley’s public life. As in Canada, there were

factions and defections during a period of shadowy party boundaries.

After an absence of three sessions, Tilley was re-elected in 1854 and

entered the first Liberal Government of the Province, that of Charles

Fisher,t who was also a Father of Confederation. In 1855 Tilley,

prematurely, as it proved, implemented his temperance beliefs by putting

through a bill prohibiting the importation, manufacture and sale of

intoxicating liquor.

Surveying the conditions from this distance, Tilley’s prohibition

measure seems to have been the result of zeal rather than judgment.

Those were the days of almost universal drinking. No social gathering

was considered complete without it, and in that damp climate in the

pioneer age, liquor was the “cure-all” for the ills of men. The

square-rigged barques that carried timber to the seven seas returned

with vinous and spirituous cargoes, the favorite being Jamaica rum from

the West Indies. In 1838 the 120,000 people of New Brunswick consumed

312,298 gallons of rum, gin and whiskey and 64,579 gallons of brandy.

Tilley introduced his prohibition bill as a private member. It was first

considered on March 19, and passed on the 27th. The narrow margin of 21

to 18 should have warned the promoter, but on the last day of the year

the supposed end of the reign of King Alcohol was celebrated by the

pealing of bells at midnight. It was not long before the law was seen to

be a dead letter. There were 200 taverns in St. John and suburbs alone,

and liquor continued to be sold. In a few months an unsympathetic

Governor, H. T. Manners-Sutton, dissolved the Assembly, the- Government

was defeated and the new Gray-Wilmot Ministry repealed the act. Fisher

and Tilley gained power again in 1857 and enacted much advanced

legislation, including vote by ballot, the enlargement of the franchise

and quadrennial parliaments.

During his long public service Tilley was essentially the business man

in politics. A man who could retire with a competency at 37 was one

whose advice was sought by visionary and impractical politicians. His

sound character and judgment put him in the forefront wherever he

happened to be. He took part in the early conferences at Quebec

regarding the Intercolonial Railway, the construction of which was

greatly delayed by circumstances. He was an influential figure at the

Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences, and helped frame the B.N.A. Act in

London. When he had at length secured the adoption of union in his own

Province he turned his hand to the cause elsewhere. As so often happens

in personal intercourse, the contrast between him and John A. Macdonald

made them fast friends. In 1867, when forming his Confederation Cabinet,

Macdonald asked Tilley to join and to choose his own colleague from New

Brunswick. He entered as Minister of Customs and took Peter Mitchell as

Minister of Marine and Fisheries. An important part was played by Tilley

in 1868 in reconciling Howe and Nova Scotia to union. Howe had just

returned from his fruitless quest in Britain for repeal. Tilley , wrote

Macdonald from Windsor, N.S., on July 17, that he had had breakfast with

Howe and found him ready to consider Confederation if some concessions

could be made.

“The reasonable men,” Tilley wrote, “want an excuse to enable them to

hold back the violent and unreasonable of their own party, and this

excuse ought to be given them.” He urged Macdonald to visit Nova Scotia

at once, and said the nature of the concessions was not as important as

the fact that concessions would be made.

“I am not an alarmist,” he added, “but the position can only be

understood by visiting Nova Scotia. There is no use in crying peace when

there is no peace. We require wise and prudent action at this moment;

the most serious results may be produced by the opposite course.”

Macdonald was discerning enough to act upon this advice. He hastened to

Halifax, made concessions to the anti-unionists, Howe joined his

Cabinet, and serious trouble was avoided.

Though originally a Liberal and responsible for some advanced

legislation, Tilley was now firmly established in the political family

of Sir John Macdonald. From February until November, 1873, he was

Minister of Finance, resigning to become Lieutenant-Governor of New

Brunswick. The barefoot messenger boy of 1831 had come home in the

trappings of a gilded governor, and he now had years of dignity and calm

in his own Province. But the call of active politics was again to be

heard and answered.

After Sir John Macdonald and Sir Charles Tupper had swept the Dominion

in 1878. on the new National Policy platform, it fell to Tilley to

introduce the new tariff. He had abandoned the ease and comfort of

Government House at Fredericton to return to the hurly-burly of

political life. He became Minister of Finance in the joyous home-comin’g

of the Conservatives, and on March 14 following enunciated the National

Policy. His three hours’ speech was somewhat dreary, as he lacked the

magic to make figures glow, but it stands as the argument for the policy

which has persisted ever since with little modification. He could refer

with truth to the depressed conditions which then existed. In 1873, he

said, he could point with pride and satisfaction to the increased

capital of the banks and the large dividends they paid. “To-day, I

regret to say, we must point to depreciated values and to small

dividends. Then I could point to the general prosperity of the country.

To-day we must all admit that it is greatly depressed.”

What was afterwards for years denounced by the Liberals as the “Red

Parlor” had its origin at this time. This was the consultation between

the Government and the manufacturers as to the amount of protection

various industries ought to have.

“We have invited,” said Tilley, “gentlemen from all parts of the

Dominion and representing all the interests in the Dominion, to assist

us in the readjustment of the tariff, because we did not feel, though

perhaps we possessed an average intelligence in ordinary government

matters, we did not feel that we knew everything.” The Government was

confronted at the time with falling revenues, for the ad valorem duties

generally in force in Canada made the customs receipts drop as values

fell. Tilley said he regretted the necessity for increased taxation, but

promised that taxation would be heavier on goods from, foreign countries

than from the mother country. So far as the United States was concerned

he expressed no regret, for Canada had expected to lead them into better

trade relations, but in vain. The new schedules, generally speaking,

increased the rates from 1 lxk per cent, to 20 and even to 40 per cent.

Tilley said he thought these “would be ample protection to all who are

seeking it and who have a right to expect it.”

“The time has arrived, I think,” he said, “when it becomes our duty to

decide whether the thousands of men throughout the length and breadth of

this country who are unemployed shall seek employment in another country

or shall find it in this Dominion; the time has arrived when we are to

decide whether we shall be simply hewers of wood and drawers of water;

whether we shall be simply agriculturists raising wheat, and lumbermen

producing more lumber than we can use, or Great Britain and the United

States will take from us at remunerative prices; whether we will confine

ourselves to the fisheries and certain other small industries and cease

to be what we have been, and not rise to what I believe we are destined

to be under wise and judicious legislation—or whether we will inaugurate

a policy that will by its provisions say to the industries of the

country: We will give you sufficient protection; we will give you a

market for what you can produce; we will say that while our neighbors

built up a Chinese wall, we will impose a reasonable duty upon their

products coming into this country; at all events, we will maintain for

our agricultural and other products largely the market of our own

Dominion. The time has certainly arrived when we must consider whether

we will allow matters to remain as they are, with the result of being an

unimportant and uninteresting portion of her Majesty’s Dominions, or

will rise to the position which I believe Providence has destined us to

occupy by means which, I believe, though I may be over-sanguine, which

the country believes are calculated to bring prosperity and happiness to

the people, to give employment to the thousands who are unemployed, and

to make this a great and prosperous country, as all desire and hope it

will be.”

Sir Leonard (he had been knighted in 1879) continued as Finance Minister

until October 31, 1885, when failing vigor compelled him to resign as

his “only chance of a measure of health and possibly a few more years of

life.” He was again appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick, and

continued to hold office for almost eight years further. He was now the

victim of an incurable disease, and when he finally lay down the reins

he knew he had not many years to live. He went in and out among his

people for three years more, respected and loved by the thousands to

whom he was personally known and for whose welfare he had always been

solicitous. In June, 1896, his illness took a fatal turn, and he passed

away on the 25th. Just before he lost consciousness on the 23rd the

first returns of the Dominion election which was to sweep his party from

power were given him. At that moment they appeared favorable and the

dying gladiator said: “I can go to sleep now; New Brunswick has done

well.”

Thus passed a statesman whose life was an example and whose record was

an inspiration. He was a lucid but not a brilliant speaker. He was a man

of sense and judgment rather than emotion and display. He was honest and

he ever looked for the good and noble in others. As New Brunswick’s

foremost son he takes his place among the greatest of the builders of

the new Dominion. |