|

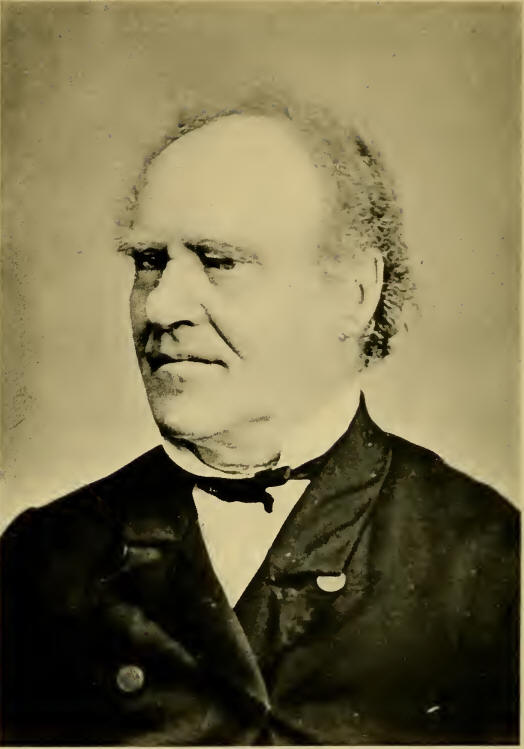

(1804-1873)

JOSEPH HOWE is not to

be measured by his failures, but by his triumphs. His powerful

constructive mind dominated his Province for thirty years, but

misjudgment and jealousy, the faults of a temperament, brought all but

disaster. A man who had peaceably accomplished responsible government in

Nova Scotia, had conceived a great railway policy to unite British

America, and had drawn his people to him as about an idol, was

singularly unequal to the rebirth of a nation. Whatever Howe’s faults of

emotion or judgment, as revealed by his opposition to Confederation, he

stands as the greatest Nova Scotian, the incarnation of his people,. He

grew up among them, he lived in their homes, he expressed their

thoughts, he fought their enemies. He had an easy manner, and he was

“Joe” to the entire Province. His magnetism won friendships, his

eloquence thrilled until often he made the flesh creep, while his

audience lost themselves in ecstasy and admiration. Wherever he sat in

any company he was the centre of interest. Men grouped around him

listening for his wisdom, laughing at his jokes, and ignoring others of

less charm and magnetism.

Howe’s record of creative work for his Province is imposing. As early as

1835, he advocated a railway from Halifax to Windsor. Three years later

he visited England, and with representatives of other colonies secured a

steam mail service to Halifax. For ten years he fought the Tory

magistrates until responsible government was granted. In 1850 he

advocated government construction of railways. At various times he spoke

of the union of the British American colonies as probable and desirable,

yet when the moment for Confederation arrived he forsook his old ideas

and was prepared to resist it by force.

That Howe should have been an opponent of Confederation was as illogical

as it was unfortunate. It is the truth to say he had passed his zenith

and that his great work was done. He never stood higher than when he

smashed the Family Compact. Thereafter he sought work which was not

readily to be found. He implored the British Government for a post in a

wider field. After years of waiting, he was finally serving as an

Imperial Fisheries Inspector when the federation movement crystallized

in 1864. He was invited to the Charlottetown Conference, but declined

when the British Admiral refused permission. On such slender threads

does history depend! Howe had advocated federation in 1849, in a letter

to George Moffat of Montreal; he had supported it in the Assembly in

1854; in 1861 had moved a resolution favoring it, and as late as August,

1864, had spoken for it during the visit to Halifax of Canadian

delegates of good-will. Yet he returned from his fisheries inspection in

troubled mind, and was soon to swallow his own policy and almost destroy

a vast scheme of union.

There is little doubt that if Howe had gone to Charlottetown and Quebec

the history of the period would have been materially different. His

sensitive poetic mind rebelled at the success of the great plan without

his aid. There was also personal feeling, as expressed in the remark: “I

will not play second fiddle to that Tupper.” The doughty warrior from

Cumberland had now trailed him for twelve years. In 1852 Tupper, then a

young country doctor, had appeared at a Howe meeting and asked to be

heard.

“Let us hear the little doctor by all means,” was Howe’s patronizing

reply. “I would not be any more affected by anything he might say than

by the mewing of yonder kitten.”

Such a boat soon brought its retribution, for Tupper was to become

Howe’s relentless antagonist. Howe’s ultimate acceptance of union and

his entry into the Dominion Cabinet were concessions which went far to

quiet the repeal agitation, though resentment in Nova Scotia lasted for

a generation.

It is doubtful if the history of British America holds a parallel to the

case of Howe and his relation to Nova Scotia. He was born on December

13, 1804, in a cottage by the Northwest Arm, near Halifax. His father,

John Howe, had been a loyalist refugee from Massachusetts, after

witnessing the disaster to the British cause at Bunker Hill. The lad was

born in the heart of beautiful nature, and during youth developed his

body and gratified his poetic soul by rambles over the hills and by the

seashore. Years afterwards a woman who had been one of “Joe’s”

schoolmates said of him: “Why, he was a regular dunce; he had a big

nose, a big mouth and a great big ugly head; and he used to chase me to

death on my way home from school.”

These school days, so riotous with mischief and fun, ended at 13, when

Joe entered the office of the Halifax Gazette as errand boy. One day he

was a witness in court, and the Judge, thinking to take a rise out of

him, said:

“So you are the devil?”

“Yes, sir, in the office, but not in the courthouse,” was the crushing

reply.

At this period Howe began the constant serious reading which went far to

fit him for his future usefulness. He also wrote poetry, a diversion

which continued for many years. In 1827 Howe and a friend bought the

Weekly Chronicle and changed it to The Acadian, with the former as

editor. The next year he married Catherine Susan Ann Macnab, a woman of

sweetness and charm, who did much to moderate his excesses. Early in

1828 he purchased The Nova Scotian for £1,050, becoming sole editor and

proprieter. Howe was now established as a citizen, and for the next

several years he studied at the best of the politician’s colleges, the

farmer’s fireside. He tramped and rode over the Province, stopped at the

farm houses, kissed the women, played with the children, and wrote his

observations and impressions under the heading, “Eastern and Western

Rambles.” His relative and friend, William An-nand, writes of this

period:

“I have often seen him during this time worn out with labor, drawing

draughts of refreshment alternately from Bulwer’s last novel or from

Grotius on National Law. His constitution was vigorous, his zeal

unflagging. It was no uncommon thing for him to be a month or two in the

saddle; or after a rubber of racquets, in which he excelled, and of

which he was very fond, to read and write for four or five consecutive

days without going out of the house.”

Howe was now storing up the information which, touched by the magnetism

and poetry of his own personality, was later to thrill scores of

audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. His voice was heard on every

hand in speech, in lecture and in propaganda for great causes. As late

as July, 1865, he accomplished a historic triumph when, swept from their

feet by his eloquence, a great hostile gathering at the International

Commercial Convention at Detroit declared for a renewal of the

reciprocity treaty with British America.

“I have never prayed for the gift of eloquence till now,” Howe began his

Detroit speech. “Although I have passed through a long public life, I

never was called upon to discuss a question so important in the presence

of a body of representative men so large. I see before me merchants who

think in millions and whose daily transactions would sweep the harvest

of a Greek island or of a Russian principality. I see before me the men

who whiten the ocean and the great lakes with the sails of commerce—who

own the railroads, canals and telegraphs, which spread life and

civilization through this great country, making the waste plains fertile

and the wilderness to blossom as the rose. . . . I may well feel awed in

the presence of such an audience as this; but the great question which

brings us together is worthy of the audience and challenges their grave

consideration.

“What is that question? Sir, we are here to determine how best we can be

brought together in the bonds of peace, friendship and commercial

prosperity, the three great branches of the British family. . . .

For nearly two thousand years we were one family. Our fathers fought

side by side at Hastings, and heard the curfew toll. They fought in the

same ranks for the Sepulchre of our Saviour in the early and later wars.

We can wear our white and red roses without a blush and glory in the

principles these conflicts established.”

Howe proceeded in similar highly poetic and inspiring phrases, and when

he told his ecstatic hearers that one of his own sons had fought in the

army of the North, that no reward from reciprocity compensated the

parents for their hours of anxiety, but he was rewarded by his son’s

certificates of faithfulness and bravery, the audience rose and gave

“three cheers for the boy.”

Imperial relationships were equally inspiring to Howe, and his speeches

in favor of closer relations with the motherland were among the earliest

and most eloquent in the cause which afterwards won converts wherever

the flag floats. Speaking on the resolution in favor of federation moved

by Premier J. W. Johnstone in the Assembly in 1854, Howe said:

“I am not sure that even out of this discussion may not arise a spirit

of union and elevation of thought that may lead North America to cast

aside her colonial habiliments, to put on national aspects, to assert

national claims and prepare to assume national obligations. Come what

may, I do not hesitate to express my hope that from this day she shall

aspire to consolidation as an integral portion of the realm of England,

or assert her claims to a national existence.”

By 1830 Howe was writing with authority on the work of the legislators.

There was as yet no responsible government in Nova Scotia. Magistrates

ruled the cities, holding their commissions from the Crown. Howe

frequently attacked them, and on January 1, 1835, he published an

article so offensive that he was indicted for libel. So entrenched was

the old regime that Howe was advised by his lawyers that he had no case.

“I asked the lawyers to lend me their books,” he said afterwards. “I

gathered an armful, threw myself on a sofa, and read libel for a week.”

The trial was a celebrated one. Howe warmed up as he proceeded, and at

the end of a speech of over six hours in his own defence he was

acquitted. The magistrates thereupon resigned and a vital blow was

struck at the old system.

Howe’s place was now in Parliament. He was elected in 1836 and continued

to sit until 1863. The battle for responsible government was carried on

in the House and in his newspaper, until success came in 1847 with a

victory for the Reformers, J. B. Uniacke becoming Premier and Howe

Provincial Secretary. The battle was marked by banter as well as

bitterness. Society drew its skirts aside as the hated Radical passed,

while Howe in turn laid doggerel hands on the sacred dignity of the

Governor, Lord Falkland, in this ironical verse:

“The Lord of the Bedchamber sat in his shirt,

And D—dy the pliant was there,

And his feelings appeared to be very much hurt,

And his brow overclouded with care.”

A great storm was raised in the House, to which Howe replied that it

would have been Very much worse if he had said the lord had no shirt.

Falkland was subsequently recalled and sent to Bombay. During this

memorable period the ablest exponent of the old theory was Thomas

Chandler Haliburton, author of “Sam Slick,” and one of Howe’s personal

friends. At this time Upper and Lower Canada were in rebellion to

achieve the same end of responsible government, but Howe, who had an

exceptional reverence for the old land, frequently declared his

disapproval of attempts to “bully the British Government.”

Howe’s conception of a future federated British America was one of the

earliest, and remains one of the most inspiring and poetic. Speaking at

Halifax, in 1851, on his return from England, where he had secured the

offer of an Imperial guarantee to build an intercolonial railway, he

said:

“She virtually says to us by the offe»:—There are seven millions of

sovereigns at half the price that your neighbors pay in the markets of

the world; construct your railways; people your waste lands; organize

and improve the boundless territory beneath your feet; learn to rely

upon and to defend yourselves, and God speed you in the formation of

national character and national institutions.”

The idea of a wide nation developed as Howe unfolded prophetically his

dream to a then receptive audience:

“Throwing aside the more bleak and inhospitable regions, we have a

magnificent country between Canada and the Pacific, out of which five or

six noble Provinces may be formed, larger than any we have, and

presenting to the hand of industry and to the eye of speculation every

variety of soil, climate and resource. With such a territory as this to

overrun, organize and improve, think you that we shall stop even at the

western bounds of Canada, or even at the shores of the Pacific?

Vancouver’s Island, with its vast coal measures, lies beyond. The

beautiful islands of the Pacific and the growing commerce of the ocean

are beyond. Populous China and the rich East are beyond; and the sails

of our children’s children will reflect as familiarly the sunbeams of

the South as they now brave the angry tempests of the North. The

Maritime Provinces which I now address are but the Atlantic frontage of

this boundless and prolific region—the wharves upon which its business

will be transacted and beside which its rich argosies are to lie. . .

“I am neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet, yet I will venture to

predict that in five years we shall make the journey to Quebec and

Montreal and home through Portland and St. John, by rail; and I believe

that many in this room will live to hear the whistle of the steam-engine

in the passes of the Rocky Mountains and to make the journey from

Halifax to the Pacific in five or six days.”

In the full flush of his success abroad and his reception at home, where

the people were ready enough to serve as the frontage of a great nation,

Howe set out in June, 1851, for Canada. In Toronto, with E. B. Chandler

of New Brunswick, he made an agreement with Sir Francis Hincks for

Canada’s part in the Intercolonial Railway scheme. Then came

disappointment. Lord Grey limited the guarantee to a railway connecting

the three Provinces and excluding the Portland line. New Brunswick at

once, and naturally, withdrew from the scheme, though the next year they

offered to join if the line were diverted to the St. John Valley. The

failure was a sad blow to Howe. He was depressed, his Province was cold,

and he was never quite the same again. The Grand Trunk meantime got a

start in England, and the Intercolonial was not completed for another

quarter century.

Bitterness as well as disappointment and jealousy was written in Howe’s

words against Confederation. The Charlottetown Conference in the summer

of 1864 was called at the instance of Premier Charles Tupper and the

Nova Scotia Assembly to discuss a Maritime Union. The Canadian delegates

swayed, if they did not stampede, the East into the larger scheme, and

adjourned to Quebec, to settle the details. Howe returned from

Newfoundland to find the plans far advanced,—farther, in fact, than the

people seemed to wish.

“What does Howe think of Confederation?” was in everyone’s mind. Already

there were suspicion and disquiet, but the opposition lacked leadership.

By January, 1865, Howe was in form, with a suggestion of his old

raillery, in a series of letters in the Halifax Chronicle called “The

Botheration Scheme.” The same month he set down his objections in a

letter to Lord John Russell. He contended that the Maritime Provinces

would be swamped by the Canadians, that the scheme was cumbrous and

would require a tariff and ultimately protection, and that in England no

important change is made in the machinery of government without an

appeal to the country.

The anti-unionists now became so aggressive that progress was held up.

Tupper, in the Nova Scotia Assembly, awaited developments, and only made

headway after New Brunswick had ratified the plan in the spring of 1866.

He then secured, after bitter debate, the adoption of a seemingly

innocent resolution favoring consultation with the Imperial Government

on the question. This was all that was needed. Canada and New Brunswick

also sent delegates to the London Conference, which drafted the

Confederation bill. In the meantime Howe, Annand, and later, Hugh

McDonald, campaigned in England for six months against union, on behalf

of the League of the Maritime Provinces. Howe’s letters to William J.

Stairs of Halifax, recently published by the Royal Society, show the

resourcefulness and persistence of his efforts. He wrote copiously

against the union scheme, in pamphlets and letters to public men,

interviewed statesmen and editors in behalf of the losing cause, but

finally had to admit defeat. In one of his pamphlets he proposed an

Imperial federation for all colonies having responsible government.

“We are now approaching a crisis,” he wrote on January 19, 1867. “We are

prepared for the worst, and if it comes, the consciousness that we have

done our best to avoid it will always console us.”

William Garvie of Halifax, who was attached to the party, gives a shock

to our sense of the importance of the bill when he describes its passage

through the British Parliament. “‘Moved that Clauses 73, 74, 75 pass,’

and they were passed sure enough,” he writes, quoting the Chairman of

Committee, in his expeditious method. Garvie also says: “The Grand Trunk

influence had a powerful effect on the Government, who, though weak,

were glad enough to bargain about votes for a Reform bill on condition

of a Confederation policy.”

Howe and the anti-unionists had not yet played their last card.

Confederation became effective July 1, 1867, thus wiping out the

sovereign powers of the Nova Scotia Assembly, but the people had still

to be heard from. On his return from England, Howe began a campaign that

threatened to drive a section of the new Dominion into rebellion or

annexation.

“I believe from the bottom of my heart,” he said at Halifax in June,

“that this union will be disastrous. At present we have no control of

our revenues, our trade and of our affairs. (A voice: “Let us hold it.”)

Aye, hold it I would; and I have no hesitation in saying that if it were

not for my respect for the British flag and my allegiance to my

Sovereign—if the British forces were withdrawn from the country and this

issue were left to be tried out between Canadians and ourselves, I would

take every son I have and die on the frontier before I would submit to

this outrage.”

The elections a few weeks later showed that the people of Nova Scotia

were of a similar mind regarding the “outrage.” Out of 19 seats, Howe

and the antiunionists carried 18, the only unionist to be returned being

Tupper. On election night Howe was hailed once more as a popular idol

and received in triumph in Halifax. At the station he entered a carriage

drawn by six horses and proceeded through the streets to the Parade.

“All our revenues are to be taken by the general government, and we get

back 80 cents per head, the price of a sheepskin,” was the Howe slogan,

alluding to the federal subsidy to the Provinces, and he pressed this on

the House of Commons at Ottawa in the first session after Confederation.

There was a thrill when the great enemy of the union rose to address the

new Dominion House. “He struck an imperious attitude and slowly swept

his glance around the chamber and the galleries,” says J. E. B. McCready,

who witnessed the scene. “It seemed as if another Samson were making

ready to grasp with mighty hands the pillars of our national fabric and

overwhelm it in ruin.”

Howe declared his

Province would read the Speech from the Throne in sorrow and

humiliation. He drew a contrast between the Nova Scotia that had been

—prosperous, free and glorious, her ships carrying the British flag from

her native ports to every sea—and the Nova Scotia now betrayed,

prostrate, bleeding, her principles gone, her treasury rifled, and her

sons and daughters sold for 80 cents a head, the price of a sheepskin.

Tupper replied in his usual confident manner, and unhesitatingly

pictured results of prosperity and happiness that would flow to Nova

Scotia.

Suddenly Howe was gone from Ottawa. Report said he had left for- London,

and it developed that he and William Annand had departed on their last

chance, to ask the Imperial Government to repeal Confederation. It

naturally fell to Tupper to follow. Then occurred in London one of the

most dramatic incidents of the Confederation battle. Howe was now past

60, a somewhat weakened and dispirited man. He was the symbol of a

losing cause, a desolate figure, facing a vigorous, determined man, with

power and success on his side. Long afterwards, as he himself passed

down the hill towards sunset, Sir Charles Tupper wrote the story of that

momentous interview when he, following Howe to London, sought his old

antagonist.

“I can’t say that I am glad to see you,” said Howe, “but we have to make

the best of it.”

“I will not insult you by suggesting that you should fail to undertake

the mission that brought you here,” said Tupper. “When you find out,

however, that the Imperial Government and Parliament are overwhelmingly

against you, it is important for you to consider the next step.”

Howe replied: “I have eight hundred men in each county in Nova Scotia

who will take an oath that they will never pay a cent of taxation to the

Dominion. I defy the Government to enforce Confederation.”

“You have no power of taxation, Howe,” Tupper replied, “and in a few

years you will have every sensible man cursing you, as there will be no

money for schools, roads or bridges. I will not ask that troops be sent

to Nova Scotia, but I shall recommend that, if the people refuse to obey

the law, the federal subsidy be withheld.”

“Howe,” he continued, “you have a majority at your back, but if you

enter the Cabinet and assist in carrying out the work of Confederation,

you will find me as strong a supporter as I have been an opponent.” “I

saw at once that Howe was completely staggered,” Tupper adds, “and two

hours of free and frank discussion followed.” That night he wrote Sir

John Macdonald he thought Howe would enter the Cabinet. Howe’s version

of the interview is not less interesting.

“We were honored by a visit from Tupper immediately on his arrival in

London,” he says. “Of course he assumes that we will be beaten here, and

is most anxious about what is to come after, and desirous that we shall

then lay down our arms. He thinks the Canadians will offer us any terms,

and that he and I combined might rule the Dominion. Of course I gave him

no satisfaction.”

Though the greatest of the anti-unionists was weakening, the fire of

repeal had gained much headway. Howe returned to Halifax in a troubled

state of mind. Conferences were held with the other leaders, and he

counselled against further resistance. In doing so he lost most of his

friends, but he acted from the broadest motives. Sir John Macdonald and

Sir George Cartier went to Halifax to confer with Howe, and a meeting

was held with Sir John Rose, Finance Minister, with the result that

better terms, including an increase of $80,000 in annual subsidy for ten

years, were offered to Nova Scotia. Howe accepted this, but more

reluctantly the accompanying condition, that he enter the Federal

Cabinet. On this he had no alternative, for Sir John represented that

the better terms could not be carried without some assurance that the

repeal agitation would cease. However, by this act, Howe cut adrift from

his Nova Scotia allies, including Premier Annand, who never forgave him.

Howe’s sun was almost set. The by-election in Hants which followed on

his entering the Cabinet broke his health, and was the severest struggle

of his political career. Tupper backed him strongly, and the slogan of

“Howe and Better Terms” won. At a meeting at Nine Mile River one night,

Howe lay on the platform in physical agony while his opponent,

nick-named “Roaring Billows,” denounced him. Howe subsequently served as

President of the Council and Secretary of State, but did not add to his

fame. He visited the Red River Settlement in 1869, in connection with

the acquisition of Rupert’s Land. His conduct on this occasion resulted

in an ill-tempered controversy with William McDougall, a Cabinet

colleague. In the next election, he and Tupper swept the Province for

Confederation, and in 1873, after he had criticized the Pacific Railway

policy at Ottawa, he was appointed, at the request of his old rival

Tupper, to the post of Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia.

When Howe left Ottawa on April 19, a crowd of fellow-members saw him off

and presented an address in which they spoke of the “unprecedented

duration and great value of his public services.” It was apparent that

he would never return.

The tribune of the people was at last in a haven of rest, but he lived

only a few weeks to enjoy it. Weakened by hard campaigning, incessant

toil and much worry, the human machine broke down and he collapsed in

his son’s arms, dying on June 1, 1873.

In the silence of his death there was a revulsion from the antipathy of

the years of battle. Through the dim, old city, out along the jagged

coast line, in the back townships where Joe Howe’s grey suit and smiling

face were still a happy memory, there was the sorrow that comes when a

great man who is also a personal friend passes from life. The world

remembers Howe as a rugged radical, a pioneer Imperialist, a peerless

orator, a creative statesman; his old friends in Nova Scotia remembered

him as a loving man among men. |