|

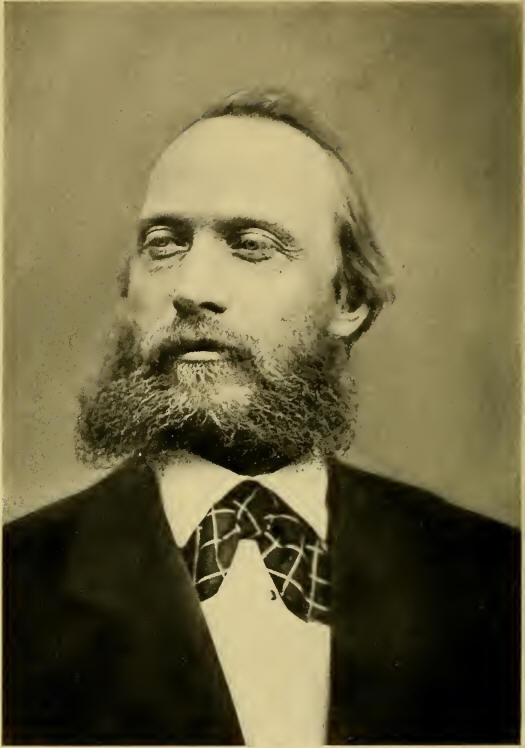

(1833-1914)

"LONG courted; won at

last.”

These words adorning an

arch of welcome in Charlottetown during the visit of Lord Dufferin, in

July, 1873, formed a naive admission from the coy maiden of the Gulf.

With Prince Edward Island it was not so much love at first sight as,

What are the terms of the marriage settlement? Nine years were occupied

by the flirtation with the unknown stranger, Confederation, and only in

the hour of her need did the Island consent to the nuptials.

It is true that David Laird said in his first speech in the House of

Commons that the Island wanted to see how Confederation was to prosper.

It is also true that the spirit of the Islanders, following 1864, was

one of suspicion of Upper and Lower Canada, carried even beyond that Of

the other Maritime Provinces. Though they had taken part in the

Charlottetown and Quebec conferences, they soon withdrew from the

scheme, and returned only when a railway burden threatened the Island’s

solvency.

David Laird, as one of the Island’s most distinguished sons, reflected

the prevailing sentiment of his day regarding union. He was not at

either Conference, and the delegates were not long home from Quebec

before he was in the fight against them. In 1873 he took the other view,

though reluctantly, and lived to render signal service to the new

Dominion. Laird was one of the noble company of able, intellectual men

whom the Maritime Provinces have sent to Ottawa, men whose calibre has

ever given the seaboard sections a high influence in Dominion councils

and overcome the disadvantages of slow development.

Scottish ancestry and inherited sterling qualities gave David Laird a

character that made for solidity and service in a pioneer commonwealth.

His father, Alexander Laird, who came from Renfrewshire to a farm in

Prince Edward Island in 1819, was a man of high character and influence.

He satin the Island Assembly for 16 years, and for four years was a

member of the Executive Council. David Laird was one of a family of

eight, and was born at New Glasgow, P.E.I., on March 12, 1833. His

higher education at the Presbyterian Theological Seminary at Truro, N.S.,

was aimed to fit him for the Church, but he entered journalism instead

as founder and editor of The Patriot at Charlottetown. A man of Laird’s

moral and intellectual strength was soon an influential citizen. He

served in the Charlottetown city council, but did not enter the Assembly

until 1871. He was elected to oppose the railway, then promoted by J. C.

Pope and his government, which Mr. Laird held was beyond the Island’s

resources.

[James Colledge Pope (1826-85) was instrumental in keeping Prince Edward

Island out of Confederation in 1866, and in bringing it in in 1873. As

Premier he moved the negative resolution in the former year, and

becoming again Premier in 1873 he accepted the better terms offer under

the Island’s financial needs consequent on its railway program. Pope

entered the Island Assembly in 1858, and was Premier three times. Being

elected to the House of Commons in 1876 he became Minister of Marine and

Fisheries, serving until his retirement in 1882.]

Progress on the Island had been retarded by the feudal system under

which the land was parcelled out in 20,000-acre blocks after the British

occupation in 1763. Absentee landlords and disheartened tenants made a

fruitful subject for politicians, but all efforts at relief had failed.

The Islanders, therefore, turned with curiosity and not without hope to

the invitation to join in the Charlottetown and Quebec conferences.

Judge their disappointment when the Quebec scheme made no provision for

a settlement of the land question and was interpreted as meaning for

them actual loss.

The Island’s delegates had joined in the ecstatic prophecies at the

conferences, but they were far ahead of their people. “It may yet be

said,” declared T. H. Haviland at Charlottetown, “that here in little

Prince Edward Island was that union formed which has produced one of the

greatest nations on the face of God’s earth.” Edward Whelan,t an alert,

eloquent Irishman, who had learned printing with Joseph Howe in Halifax,

was similarly happy. At Montreal, after the Quebec Conference, he said

the Island could support a population at least three times as great as

it then contained, and he was satisfied the Province “could not fail to

become very prosperous and happy under the proposed union.”

David Laird was one of the first to disturb the dream of the Island

delegates. Just turned thirty, his six feet four inches and his

uncommonly loud voice commanded attention at once in the battle against

the Quebec scheme. Early in 1865, The Islander newspaper, which had been

favorable to union, went to the other side, and George Coles and Edward

Palmer, two of the delegates to Quebec, gave way to pressure and spoke

against federation. Public meetings were held, and the Islanders were

told they would be marched away to the frontiers of Upper Canada to

fight for the defence of the Canadians.

Laird made an exhaustive speech against union at a meeting at

Charlottetown in February. He objected to the terms of Confederation,

and claimed each Province should have equal representation in the

Legislative Council. As to the Assembly, he protested against Montreal

having one more representative than the Island, and with “the refuse and

ignorant of its purlieus and lanes being thus placed on an equality with

the moral, independent and intelligent yeomen of Prince Edward Island.”

He estimated that the Island would be $93,780 worse off financially each

year under union.

The debate went on for several weeks, T. H. Havi-land being a leading

defender of the scheme he had helped to found. Opinion was crystallized

at a large meeting in Charlottetown where the following resolution was

adopted:

“That in the opinion of this meeting the terms of union contained in the

report of the Quebec Conference—especially those laid down in the clause

relating to representation and finance—are not such as would be either

liberal or just to Prince Edward Island, and that it is highly expedient

that said report be not adopted by our Legislature.”

Before the end of March the Assembly by 5 to 23 had failed to approve

the Quebec terms, and the idea was all but abandoned. A resolution

adopted by the Assembly early in 1866 made the plan seem even more

offensive. It said that, while union might benefit the other Provinces,

they could not admit “it could ever be accomplished on terms that would

prove advantageous to the interests and well-being of this Island,

separated as it is and must ever remain from the neighboring Provinces

by an immovable barrier of ice for many months of the year.”

Other temptations from the uniting Provinces followed. The delegates in

England framing the B.N.A. Act in 1866 made an informal offer to J. C.

Pope, who was there on a visit, of $800,000 for loss in territorial

revenue and for purchase of landlords’ rights. Three years later Premier

R. P. Haythorne rejected a further offer, on the ground that it was

inadequate.

“No union” was still the cry in 1870, when the Islanders stubbornly

opposed any change, while declaring their attachment to the British

Crown. David Laird during the session of the Legislature set forth the

Islanders’ views typically.

“It had been stated,” he said, “that in our present isolated position we

should never have any influence, but that united to Canada we should be

a part of a great nation. He would ask what constituted greatness? A

large population did not constitute greatness, or China would be the

greatest empire in the world. Neither did large extent of territory, or

Russia would be great. Neither did wealth make a country great unless

there was freedom. The greatness that was to be desired was to have

freedom of conscience and to have every man educated. We should not be

improved in these respects by joining the Dominion, and as far as wealth

was concerned, we could also compare favorably with them. We could gain

nothing commercially by uniting with the Canadians, as they grew

everything we did, and we would aid them in building railroads which

would be a means of conveyance for their produce and enable them to

supply the different markets more readily than we could.”

One year later the cause of the Island’s change of heart loomed up in a

project for a railway. This essentially modern instrument became a

reality, though Arcadian simplicity still finds expression in L. M.

Montgomery’s novels of Island life and in the prohibition until recently

of the use of automobiles. The railway was to cost $25,000 per mile, but

the prospect of a $3,000,000 debt made the bankers nervous, and within

two years the Province appeared to face bankruptcy. David Laird had

entered the Cabinet of R. P. Hay-thorne late in 1872, and, realizing the

crisis, they accepted an invitation to visit Ottawa. Haythorne and Laird

“stole away in the night,” as a critic said, by the ice-boat route to

the mainland, and reached Ottawa on February 24, 1873. They had extended

interviews with the Government, but their visit was barely noticed by

the public. Terms were offered and they went home to submit them to the

people. J. C. Pope outmanoeuvred them by promising to secure “better

terms,” and won the general election without endangering the principle

of union, which the majority now desired. Pope and Haviland then visited

Ottawa, secured some slight changes, and the union scheme was adopted

unanimously in the Legislature, becoming effective on July 1.

Pope had opposed union as had Laird, and the latter described the logic

of events during the session of 1873. “The delegates went to Ottawa,” he

said, “not to sell their country or barter away its constitution, but,

in the embarrassed state of the colony brought about by the railway

measure, to see what terms could be had.”

“In view of the present and prospective difficulties of the colony,” he

added, “they (the delegates) saw that increased taxation or

confederation was unavoidable. As a native of the country, if he saw any

possible way by which they could hope to overcome these difficulties and

remain as they were, he would feel glad, but as the railway debt would

be largely increased in another year he saw no course open but the one

they took.”

Under the agreement the Dominion Government took over the Island

Railway, which was under contract, and gave $800,000 for the purchase of

land from the proprietors and undertook various other expenses, as well

as the subsidy of 80 cents per head as in the case of the other

Provinces.

Considering the state of Canadian politics at the time, it is little

wonder that the addition of Prince Edward Island to the union made

slight stir. The Dominion was seething in 1873 over the charges and

revelations oi the Pacific Scandal, under which the Pacific Railway

Syndicate gave large sums to the Conservative party’s campaign fund. The

scandal had reached its climax in the autumn in a long debate in the

House on the report of the commission of investigation. The six members

from the Island had taken their seats for the first time, under the

leadership of David Laird. Their attitude in Federal politics was yet

unknown and was awaited with some anxiety. It was now that the sterling

qualities of David Laird were seen. He stood in the House like an

avenging angel. He began his speech on November 4 with some timidity, as

he said the Island members had not been present when the charges were

made. At the same time, he added, the members had now taken their seats,

and they would neither be faithful to their constituents nor to the

trust reposed in them if they shirked the vote upon this question. He

reviewed the case in a fresh and comprehensive manner, censured the

conduct of the Ministers involved, declared the carrying of elections by

the influence of money was a subversion of the rights of the people, and

said he was ready to vote according to his conscience.

“Upon the decision that is given on this question,” he said, “will

depend the future of the country, its intellectual progress, its

political morality and, more than all, the integrity of its statesmen.”

It was generally conceded that Mr. Laird’s speech, along with that of

Donald A. Smith (later Lord Strath-cona), had much to do with

precipitating the Government’s resignation the next day. Sir George W.

Ross, who was then a tyro in the House of Commons wrote years afterwards

that the Island leader’s speech was anxiously awaited.

“Mr. Laird,” he said, “was regarded as a man of high character, and the

Opposition could only hope that no consideration of personal or

Provincial interest would sway his judgment. . . Was ever a maiden

speech so fraught with doom? With great calmness and in a moderate tone

he declared his opposition to the Government, and the Opposition benches

rang with cheers.”

Donald A. Smith’s speech marked the revulsion of another strong mind,

and the Government could do nothing but resign, without even a vote. Two

days after Laird’s telling speech, so swiftly and unexpectedly did

events move, Alexander Mackenzie was Premier of Canada and David Laird

was his Minister of the Interior.

A new outlook now confronted the Island leader. The man who had resisted

union with the other Provinces now became a keen instrument in the

further expansion of the Dominion. It required men of his painstaking

ability, humanity and integrity to lay the foundations for the great

structure in the West. He served as Minister of the Interior until July

7, 1876, when he became the first Lieutenant-Governor of the Northwest

Territories, and moved to the boundless and all but empty plain that he

was later to see so potent a part of the Dominion. There was yet not a

mile of railway, the inhabitants were mostly red men, and the

wheat-growing possibilities were not even dreamed of. Seven years

previously Louis Riel had mustered the half-breeds to resist the white

man’s coming, butr stragglers were entering and the dawn of a new era

was seen.

No doubt Laird’s appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of the Northwest

Territories grew out of a visit which he paid to Winnipeg and the

western country in 1874. On this occasion he was one of the

commissioners appointed by the Government to negotiate a cession of

Indian territory from the aborigines. It may be interesting to note that

at the first session of the Dominion Parliament the Speech from the

Throne dealt with the advisability of extending the boundaries of the

country to the Rocky Mountains, and on December 4, 1867, the House went

into committee to consider the proposed resolutions for a union of

Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territories of Canada. Of these

resolutions No. 7 provides “That the claims of the Indian tribes to

compensation for lands required for purposes of settlement would be

considered and settled in conformity with the equitable principles which

have 306

uniformly governed the Crown in its dealings with the aborigines.” This

was simply carrying out the procedure laid down by the Proclamation of

1763. After Parliament took the necessary action, the Hudson’s Bay

interest in the Territories was purchased and the Government began to

make arrangements with the Indians for extinction of the Indian title.

Before Mr. Laird’s mission, three arrangements, which are known as

treaties, were made, whereby the Indian lands in what is now a portion

of Manitoba were ceded. The fourth treaty, which was negotiated by David

Laird and Alexander Morris, covers about 75,000 square miles of

territory, including the most fertile wheat lands in the Province of

Saskatchewan. Mr. Laird reported that the information which he acquired

at Qu’Appelle and Manitoba would aid him greatly in discharging the

responsible duties of his Department. It did more than that; it paved a

way for residence in the country and the acceptance of the highly

onerous position of Lieutenant-Governor of the Northwest Territories.

When he went to Battleford no arrangement had yet been made with the

Indians for the cession of the territory as far west as the Rocky

Mountains. In this situation his integrity and probity stood him in good

stead. To the Indians Mr. Laird was the Big Chief. With their keen

insight, they named him “The-man-whose-tongue-is-not-forked.” From his

primitive capital at Battleford he moved among his white and red

subjects, whom he ruled with a benevolent despotism. At times the

outskirts of the old Northwest capital bristled with the tents of

visiting aborigines. He had an intimate acquaintance with the Indian

leaders, such as Crowfoot, the head chief of the powerful Blackfoot

nation, and Red Crow of the Blood tribes, as also with his more

immediate neighbors, James Seenum, Mistowasis and Atahkahkoops, three

Cree chiefs, whose lands were in the vicinity of Battle-ford, and on

numerous occasions he smoked with them the pipe of peace.

His most important negotiation with the Indians . was the treaty known

as Number 7, with the Blackfoot tribes of Southern Alberta. These

Indians were the most warlike of the Territories, and as the projected

railway was to pass through their country, the negotiations with them

were most important. To make this treaty Governor Laird journeyed

hundreds of miles over the prairie to Fort Macleod. The conference with

the chiefs took place at the Blackfoot crossing of the Bow River, and

its success was the more gratifying because over the boundary United

States troops were then in conflict with Indians.

“In a very few years,” Laird told the chiefs, “the buffalo will probably

be all destroyed, and for this reason the Queen wishes to help you to

live in the future in some other way.”

The prophecy was fulfilled, for it was not long before the Government

had to supply beef for the Indians, whose nomadic herds had been swept

away forever by the greed and waste of the hunters.

Treaty No. 8 followed in 1899, when Mr. Laird, then Indian Commissioner,

journeyed more than 2,000 miles over lakes, rivers and trails north of

Edmonton.

He negotiated with the Crees, Beavers and Chippewans for the possession

of a territory 500 miles in length from the Athabasca River to the Great

Slave Lake, to be held, in the picturesque language of the red man, “as

long as the sun shines and water runs.” Cash grants each year to every

Indian were promised, as well as special reserves of land. They are now

living on reserves and reasonably prosperous and contented.

From his retirement from the Lieutenant-Gover-norship in 1881 until 1898

Mr. Laird returned to the editor’s chair in Charlottetown. In the latter

year he yielded again to the call of the West and returned as Indian

Commissioner. He was located at Winnipeg for several years, removing to

Ottawa in 1909, where his wide knowledge was sought by the Government in

an advisory capacity. Here he was serving when death overtook him, after

a week’s illness, on January 12, 1914.

Among the builders of the Canadian federation David Laird stands out for

integrity and sturdy independence. They used to call him “Dour Davie,”

and some said cynically that he was so upright as to be impracticable.

He was the keeper of an alert Presbyterian conscience, and the nation

profited by the confidence his character inspired. His reluctance

towards Confederation was typical of his environment, and has found

echoes to this day in the pleas of Island members for a tunnel and other

subventions from Ottawa. His Island home gave him a character which mere

size or wealth in any country could not supply, and he used it

faithfully as a pathfinder and placed the Dominion forever in his debt.

|