|

Artist

and technician, elitist and democratizer, the Canadian who changed

photography forever is featured in an exhibition at the Canadian Museum

of History. Artist

and technician, elitist and democratizer, the Canadian who changed

photography forever is featured in an exhibition at the Canadian Museum

of History.

His techniques predated Photoshop by about a century, but just because

we can achieve in a few clicks what would have taken William Notman days

of painstaking photography, painting, and literal cutting and pasting,

should make his legacy more impressive, not less. William Notman:

Visionary Photographer is the first-ever retrospective of his work. The

exhibition at the Canadian Museum of History originated with the McCord

Museum in Montreal, which holds a large collection of Notmanís images.

The skill and creativity evidenced in his unique large-scale

compositions is breathtaking. The exhibition shows the process Notman

used to combine individual photographs into group portraits featuring a

gentlemenís snowshoeing club, the Montreal Hunt Club or the Princess

Louise Dragoon Guards. Each image would be cut out and added to the

background and the result photographed to create a seamless whole.

Sometimes Notman included painted elements, blurring the line between

different kinds of portraiture to place dozens of people at the same

grand ball or social event. Indeed, artifice was central to much of

Notmanís work ó he was an expert at faking photos of winter activities

in his studio.

When the family textile business ran into trouble in Scotland, Notman

fled to Canada in 1856 to avoid fraud charges. He set up his photography

business in Montreal, becoming, in the exhibitionís words, ďa superb

networker.Ē He won the commission to photograph the construction of the

cityís Victoria Bridge, expanded his business to Toronto, Ottawa and

Halifax, and became an increasingly sought-after society portrait

photographer. By 1872 he had twenty-six studios around North America, 19

of them in the United States.

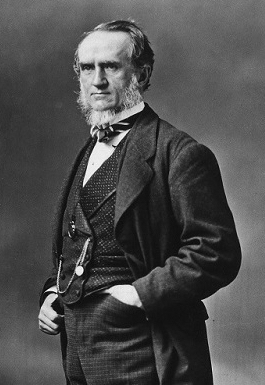

Although Notman also photographed nature and urban scenes, the images he

has left us of everyone from prominent churchmen and politicians to

ordinary Canadians are an invaluable record of our past. The wary gaze

of the soon-to-be-assassinated Thomas DíArcy McGee, the artificially

created merriment of a mass skating scene, the penetrating stare of

Sitting Bull, and the stiff formality of young women pretending to drink

tea ó through Notmanís work, they reach out across the decades and hold

us transfixed in front of their portraits. |