|

WHATEVER may be said of

Sir William Osier in days to come, of his high position in medicine, of

his gifts and versatility, to his contemporaries, love of his

fellow-man, utter unselfishness, and an extraordinary capacity for

friendship will always remain the characteristics which overshadow all

else. Few so eminent and so industrious come in return to be so widely

beloved for their own sake. Most of us do well with what Stevenson

advises—a few friends and those without capitulation —but Osier had the

God-given quality not only of being a friend with all, high or low,

child or grown-up, professor or pupil, don or scholar, but what is more,

of holding such friendships with an unforgetting tenacity— a scribbled

line of remembrance with a playful twist to it, a note of congratulation

to some delighted youngster on his first publication, the gift of an

unexpected book, an unsolicited donation for some worthy cause (and

giving promptly he gave doubly), a telegram to bring cheer or

consolation, an article to help a struggling journal to get a footing, a

cable such as his last on the day of his operation to his old Hopkins

friends, which was given by them to the press for the benefit of

countless others who shared their own anxiety—all this was

characteristic of the man, whose first thoughts were invariably for

others.

He gave much of himself to all, and everyone fortunate enough to have

been brought in contact with him shared from the beginning in the

universal feeling of devotion all had for him. This was true of his

patients, as might be expected, and he was sought far and wide not only

because of his wide knowledge of medicine and great wisdom, but because

of his generosity, sympathy and great personal charm. It was true

also—and this is more rare—of the members of his profession, for whom,

high or low, he showed a spirit of brotherly helpfulness untinctured by

those petty jealousies which sometimes mar these relationships. “Never

believe what a patient may tell you to the detriment of another

physician” was one of his sayings to students, and then he would add

with a characteristic twist— “even though you may fear it is true”; and

he was preeminently the physician to physicians and their families, and

would go out of his way unsolicited and unsparingly to help them when he

learned that they were ill or in distress of any kind. And no one could

administer encouragement, the essential factor in the art of

psychotherapy in which he was past master, or could “soothe the

heartache of any pessimistic brother,” so effectively and with so little

expenditure of time as could he.

During one of his flying trips to America some years ago, as always with

engagements innumerable, he took time to go from Baltimore to Boston for

the single purpose of seeing a surgical friend with literary tastes who

for some months had been bed-fast with a decompensated heart; and James

Mumford, for it was he, always said that this unannounced visit was what

put him on his feet again. I knew of his doing the same thing for an

Edinburgh physician of whose illness he heard by chance just as he was

leaving the steamer, in Liverpool. He was due for an address before the

British Medical Association in Oxford, but without hesitation he took

the first train to the north and managed to get back to Oxford just in

time for the address, blithe and gay as though he had not spent two

nights on a train. Indeed he was invariably punctual and somewhat

intolerant of tardiness in others. “Punctuality is the prime essential

of a physician—if invariably on time he will succeed even m the face of

professional mediocrity.”

The universal devotion he engendered was no less true of those with whom

he came in contact outside his profession, and his points of contact

through his varied interests were innumerable. Man, woman or child—and

in children especially he delighted as they did in him—felt from the

first moment of meeting a rare fascination in his personality. In a

poem, “Books and the Man,” dedicated to Osier and read before the

Charaka Club, March 4, 1905, Weir Mitchell recalls in these three verses

their first meeting in London twenty years before.

Do you perchance recall when first we met—

And gaily winged with thought the flying night

And won with ease the friendship of the mind,—

I like to call it friendship at first sight.

And then you found with us a second home,

And, in the practice of life’s happiest art

You little guessed how readily you won

The added friendship of the open heart.

And now a score of years has fled away

In noble service of life’s highest ends,

And my glad capture of a London night

Disputes with me a continent of friends.

On Osier’s seventieth birthday, just passed, the medical world set out

to do him honor—unknown to him, for he was one to elude public

testimonials and did not suffer adulation gladly, quick as he was to

give praise to others. For this occasion many of his former pupils and

colleagues in Baltimore wrote a number of papers containing the sort of

things rarely said or written about a man or his work until after his

death. Among these papers is one by his present successor there, on

“Osier the Teacher” which deserves quoting in full, but which after an

enunciation of his traits ends with this picture of the man as his

hospital associates and students remember him.

If you can practice consistently all this, . . . and then, if you can

bring into corridor and ward a light, springing step, a kindly glance, a

bright word to everyone you meet, arm passed within arm or thrown over

the shoulder of the happy student or colleague; a quick, droll,

epigrammatic question, observation or appellation that puts the patient

at his ease or brings a pleased blush to the face of the nurse; an

apprehension that grasps in a minute the kernel of the situation, and a

memory teeming with instances and examples that throw light on the

question; an unusual power of succinct statement and picturesque

expression, exercised quietly, modestly and wholly without sensation; if

you can bring into the Iecturc-room an air of perfect simplicity and

directness, and, behind it all, have an ever-ready store of the most-apt

and sometimes surprising interjections that so light up and emphasize

that which you are setting forth that no one in the room can forget it;

if you can enter the sick-room with a song and an epigram, an air of

gaiety, an atmosphere that lifts the invalid instantly out of his ills,

that produces in the waiting hypochondriac so pleasing a confusion of

thought that the written list of questions and complaints, carefully

complied and treasured for the moment of the visit, is almost invariably

forgotten; if the joy of your visit can make half a ward forget the

symptoms that it fancied were important, until you are gone; if you can

truly love your fellow and, having said evil of no man, be loved by all;

if you can select a wife with a heart as big as your own, whose generous

welcome makes your tea-table a Mecca; ... if you can do all this, you

may begin to be to others the teacher that “the chief” is to us.

Little wonder that he was idolized by the students. This was natural

enough, but he in turn took pains to know them by name, gave up an

evening in each week to successive groups of them at his home, learned

them as individuals and never forgot them. And it was the same with his

hospital juniors, whether they happened to be members of his own staff

or not. Preserved among some papers I find this characteristic undated

note of circa 1898, concerning an early effort which had been submitted

to him. It is scribbled in pencil on a bit of paper.

A. A. 1. report! I have added a brief note about the diagnoses. I would

mention in the medical report the name of the House Physician in Ward E

& the clin. clerk, & under the surgical report the name of the House

Surgeon who had charge. We are not nearly particular enough in this

respect and should follow the good old Scotch custom. Yours, W. O.

This habit of giving credit to everyone who may have been brought into

contact with a case was most characteristic of the man. Even his

“Text-Book of Medicine” contains so many references to places and people

that it led to these amusing verses taken from a long poem by a student

which appeared in the Guy’s Hospital Gazette some years ago:

For why should it matter to usward,

If Osborn has sent you a screed,

Or why have you sought a brief mention of Porter,

Or Barker, or Caton, or Reed?

I sometimes am seized with a yearning,

In Appleton’s ledger to look,

What fun it would be if we only could see

Whether each of them purchased the book!

But when of the names we are weary

(Directories muddle the brain),

We’re provided by you with philosophy too

In the trite Aphorisms of Cheyne.

Geography also you teach us,

Until I came under your thrall,

I don’t mind confessing that

Conoquenessing I never had heard of at all.

But with all his abundant learning, his high spirits, his playful wit

and love of a practical joke, he was incapable of offending. “If you

can’t see good in people see nothing.” Charitable to a degree of others’

foibles, even when he had to oppose or to fight in public for a

principle he did so without leaving hurt feelings. This lay at the

bottom of the great influence he exercised and the universal admiration

felt for his character.

Probably no physician during his life has been so much quoted nor so

much written about, and the chief periods of Osier’s eventful and

migratory career are too well known to need more than brief mention.

His father, a clergyman, Featherstone Lake Osier, with his wife, Ellen

Pickton, left Falmouth, England, in 1837 and settled in the Province of

Ontario. William, the eighth of their nine children, several of whom

have become highly distinguished in Canadian affairs and in the law, was

born July 12, 1849, at Bond Head. A graduate of Trinity College,

Toronto, in 1868, he took his medical degree four years later at McGill

University; then after two years of study abroad, returning to Montreal

in 1874, leapt into prominence as the newly appointed Professor of the

Institutes of Medicine of his alma mater. A professor at twenty-five, in

a chair which covered the teaching of pathology and physiology I And

there followed ten years of active scientific work which laid the

foundation for his subsequent eminence in his profession.

In 1884 he accepted a position in the University of Pennsylvania, and

five years later was called to Baltimore as Professor of Medicine in the

newly established Johns Hopkins Medical School. There, marrying in 1892

Grace Revere, the widow of Dr. S. W. Gross of Philadelphia, he remained

for sixteen years. It was the Golden Age of the Johns Hopkins during the

presidency of Daniel C. Gilman, and during this period through his

writing and teaching Osier became recognized, one may say without

exaggeration, as the most eminent and widely influential physician of

his time.

Many calls to other positions during these years met with refusal until

in 1904, when fifty-six years of age, he accepted the Regius

Professorship of Physic at Oxford, the most honored post in medicine

that the United Kingdom can offer. Though this position on a royal

foundation centuries old (Henry VIII, 1546) is a sinecure and was

doubtless accepted to give leisure for literary pursuits, he was not one

to take advantage of ease. The succeeding fifteen years in Oxford

represent, if possible, a period of even greater activity and, more

far-reaching influence in many directions than the fifteen years at the

Johns Hopkins, where despite his absence his stimulating spirit of work

for work’s sake still reigns.

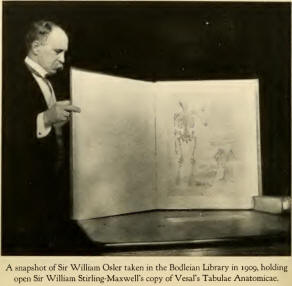

Established in a delightful home where he and Lady Osier continued to

dispense their unbounded hospitality, so much so that 13 Norham Gardens

came to be known as the “Open Arms,” elected a Fellow of Christ Church,

Woolsey’s College, put upon the Hebdomadal Council, a small body which

takes the initiative in promulgating all the legislature of the

University before its submission to Convocation, he was soon appointed

one of the curators of the Bodleian Library, and elected a Delegate of

the University Press. There can be no doubt but that these latter

positions gave him his greatest extra-professional pleasure and

satisfaction during his Oxford life, and to the Library and the Press he

gave largely of his time.

But Oxford, with its hoary traditions, its strict adherence to the

humanities, its comfortable spirit of laissez faire, had drawn into its

net a restless spirit who knew the modern outside world, and he was

responsible for such changes even in the established procedures of the

Bodleian as were thought impossible of accomplishment, if indeed modern

library methods were really desirable. But a man, particularly when

energetic, unselfish and likeable, who could talk Aristotelian

philosophy with the dons at the high table and at the same time knew

science and the value of laboratories as well as libraries, could not

but leave his impression on the ten centuries, more or less, of Oxford’s

habits and customs.

There were, indeed, many Osiers: the physician, the professor, the

scholar, the author, the bibliophile, the historian, the philanthropist,

the friend and companion for young or old. Though no man loved his home

more nor kept its doors more widely open to the world, he was in demand

everywhere, and was eminently clubable. Few dinners, of the Samuel Pepys

Club, the Roxburghe or the Colophon Clubs, of the inner circle of the

Royal Society, of his college, failed to be enlivened by his presence,

and he had just been made a member of the famous Johnson Club, one of

the oldest and most select dining clubs in existence. .

His Oxford home, even more than in Baltimore, had become such a

gathering place, particularly for Canadians and Americans, that how the

scholar did his work was a mystification to many. An omniverous reader

with a most retentive memory, possessed of a rare literary gift and with

the power of immediately concentrating on the thing which was to be

done, no matter what had occupied his attention the moment before or was

laid out to be done the moment after—these were probably the elements of

his great productivity.

With it all he was a writer par excellence of countless brief

missives—even the fragment pencilled on a postcard during his outings

and sent to an unexpecting friend whom some incident had led him to

recall, invariably contained some characteristic message, quip or

epigram worth preserving. During a brief sojourn in Paris in the winter

of 1908-9, he writes:

I’ve just been going through the Servetus Trial for Astrology, 1537.

’Tis given in full in du Bou-Iay’s History of the University of Paris. I

wish you could see this library. I’ve wasted hours browsing.

Meanwhile I’ve read through six volumes of Swinburne. I did not know

before of his Children’s Poems. We are off on the 13th, first to Lyons

to see Symphorien Champier and Rabelais. We’ll stop at Vienne to call on

Servetus and Appolos Revoire, doubtless the father of the late Paul

Revere.

He subsequently went down into Italy, and some of the readers of a

journal of medical history may like to trail him by a letter and by some

picture postcards, on a quarter of which he could squeeze much in his

fine writing.

Cannes.

A great coast. Such sunshine. We have been here \l/i weeks—delighted

with everything. This is a gorgeous spot. Where I put the is the little

town of Gourdron. They had to get high up on account of the Moors. I am

thinking of settling at Monte-Carlo—they say there is a good opening. I

lost S.25 in five minutes and then stopped. We go to Rome on the 7th. So

far as women are concerned this is the Remnant Counter of Europe.

Milan.

I forgot whether I wrote about the Vesal Tabular sex at the San Marco— I

think I did. Splendid as illustrating the evolution of his

knowledge—also of Calcar as they are very crude in comparison with the

1542. Nothing much in Pavia—nothing in comparison with Bologna and

Padua. Library good—no Vesal items of moment, not even the 1543. A 1st

ed. of Mundinus, but no plates. I have not been able to locate a single

Mundinus MS.—I wonder where they can be. The Ambrosiana here is a fine

collection. I had 5 original MSS. of Cardan to look over—the

autobiography is complete—he wrote a wonderful hand—no wonder the

printers liked to get his copy. Hopli here has no large stock—tho’ the

best publisher in Italy. Love to the bairns.

Rome.

Rome at last! Wonderful! What pigmies we are in comparison with those

old fellows. So much to see and everything intensely interesting. I have

not yet been to the Vatican Library. Splendid bookshops here. I have

already got some treasures. Redi and Valisneri—splendid editions. So

glad of your letter today (i ith). Love to the darlings.

Florence.

Yours came this morning—two days late for personal attention to your

Lang commission. I was recalled to Rome (stranded American) and I

sanctified my fee by buying three copies of Vesal. 2nd edition, fine one

for myself. A first for McGill (300 fr. was stiff but it goes for 500!)

and another for the Frick Library. I was sorry to miss the Rhazes—the

Brussels Library secured it. I have two copies also of the Venice

edition of the Vesal. Have you one? I will send your list to Lang. They

are Germans and know their worth. I bought one Imperialis for the sake

of the Vesal picture—they have another which I will ask them to send.

The Gilbert facsimile is good and the Berengarius. Did I tell you I got

the original Gilbert at the Amherst sale? I got a beauty Aristotle 1476

de partibus animalium at Laschers. This place is of overwhelming

interest—libraries, pictures, etc. The Laurentian library is just too

splendid for words —7000 chained mss., all in the puter designed by

Michael Angelo. I have a photo of the end of one for you. The book shops

are good, one of the best in Europe. He has 500 incunabula on the

shelves, a Silvaticus—a cuss of no moment —of 1476, a superb folio, one

of the first printed in Bologna—fresh and clean as if printed yesterday

and such a page! but . . . asks 1500 francs. His things are wonderful.

But really auction sales (are) is the only economical way to get old

books. The dealers have to put up their prices to pay interest on the

stock. I am sorry not to have seen the Junta.

Galen—there are 5 Venice editions of that firm! By the way the Pitti

picture of Vesal is very fine —I am looking for a photo—the beard is

tinged with grey.

Re Alcmeon, see Gomperz Greek Thinkers—he was the earliest and greatest

of the Magna Graeca anatomists. We go from here to Bologna, Padua,

Venice, &c. I have a set of Votives for the Faculty —terra-cotta arms,

legs, breasts, yards, eyes, ears, fingers—which the votaries hung in the

Aisculapian temples in gratitude to the God— the modern R. C. ones are

wretched (tin) imitations.

I am in a state of acute mental indigestion from plethora—it is really

bewildering—so much to see and to do.

Naples.

Thus far on the trip. Glorious place—glorious weather. I wish you were

mit. I dreamt of you last night—operating on Hughlings Jackson. The

great principle you said in cerebral surgery was to create a commotion

by which the association paths were restored. You took off the

scalp—like a p. m. incision—made a big hole over the cerebellum and put

in a Christ Church—whipped cream —wooden instrument and rotated it

rapidly. Then put back the bone and sewed him up. You said he would

never have a fit again. I said solemnly, I am not surprised. H-J. seemed

very comfortable after the operation and bought 3 oranges from a small

Neapolitan who strolled into the Qucen-Square amphitheatre! 1 have been

studying my dreams lately and have come to the conclusion that just

one-third of my time is spent in an asylum—or should be!

Two years later, in 1911, he made a winter’s trip to Egypt and as usual

was enthusiastic about all he saw and did. Here is a somewhat longer

letter.

S. S. "Seti”

Feb. 22nd, 1911.

Such a trip! I would give one of the fragments of Osiris to have you two

on this boat. Everything arranged for our comfort and the dearest old

dragoman who parades the deck in gorgeous attire with his string of 99

beads—each one representing an attribute of God! We shall take about 10

days to the Dam (Assouan), 580 miles from Cairo. Yesterday we stopped at

Assiut and I saw the Hospital of the American Mission—200 beds, about

20,000 out-patients. Dr. Grant is in charge with 3 assistants and many

nurses. I found there an old Clevelander . . . who had fallen off a

donkey and broken his ribs, and on the 8th day had thrombosis of left

leg. He was better, but at 76 he should have stayed at home. The Nile

itself is fascinating, an endless panorama—on one side or the other the

Arabian or the Libyan desert comes close to the river, often in great

lime stone ridges, 200-800 ft. in height; and then the valley widens to

eight or ten miles. Yellow water, brown mud, green fields and grey sand

and rocks always in sight; and the poor devils dipping up the water in

pails from one level to the other. We had a great treat yesterday

afternoon. The Pasha of this district has two sons at Oxford and their

tutor, A. L. Smith, a great friend of his, sent him a letter about our

party. He had a secretary meet us at Assuit and came up the river to

Aboutig. We had tea in his house and then visited a Manual Training

School for 100 boys, which he supports. In the evening he gave us a big

dinner. I wish you could have seen us start off on donkeys for the half

mile to his house. It was hard work talking to him through an

interpreter, but he was most interesting—a great tall Arab of very

distinguished appearance. A weird procession left his house at 10

p.m.—all of us in eve. dress, which seemed to make the donkeys very

frisky. Three lantern men, a group of donkey men, two big Arabs with

rifles and following us a group of men carrying sheep—one alive!

chickens, fruit, vegetables, eggs, etc., to stock our larder. We tie up

every eve about 8 o’clock, pegging the boat in the mud. The Arabs are

fine: our Reis, or pilot, is a direct descendant, I am sure, of Rameses

II, judging from his face. After washing himself he spreads his prayer

mat at the bow of the boat and says his prayers with the really

beautiful somatic ritual of the Muslem. The old Pasha, by the way, is a

very holy man and has been to Mecca where he keeps two lamps perpetually

burning and tended by two eunuchs. He is holy enough to do the early

morning prayer from 4 to 6 a.m. with some 2000 sentences from the Koran.

It is a great religion—no wonder Moslem rules in the East. Wonderful

crops up here—sugar cane, cotton, beans and wheat. These poor devils

work hard but now they have the satisfaction of knowing they are not

robbed. We are never out of sight of the desert and the mountains come

close on one side or the other. Today we were for miles close under

limestone heights—800-1000 feet, grey and desolate. The river is a

ceaseless panorama—the old Nile boats with curved prows and the most

remarkable sails, like big jibs, swung on a boom from the top of the

masts, usually two and the foresail the larger. I saw some great books

in the Khcdival Library—monster Korans superbly illuminated. The finer

types have been guarded jealously from the infidel, and Moritz, the

librarian, showed me examples of the finer forms that are not in any

European libraries.

Then he looked up a

reference and said—“ You have in the Bodleian three volumes of a unique

and most important 16 cent, arabic manuscript dealing with Egyptian

antiquities. We have the other two volumes. Three of the five were taken

from Egypt in the 17th century. We would give almost anything to get the

others.” And then he showed me two of the most sumptuous Korans, about 3

ft. in height, every page ablaze with gold, which he said they would

offer in exchange. I have written to E. W. B. Cyclops Nicholson urging

him to get the curator to make the exchange, but it takes a University

decree to part with a Bodley book! Curiously enough I could not find any

early Arabian books (of note) in medicine, neither Avicenna or Rhazes in

such beautiful form as we have. I have asked a young fellow at school

who is interested to look up the matter. We shall have nearly a week in

Cairo on our return. I went over the Ankylostoma specimens with Looss

and the Bilharzia with Ferguson—both terrible diseases here (not the

men!)—the latter, a hopeless one and so crippling. There were a dozen or

more bladder cases in the hospital and the polypous cholitis which it

causes is extraordinary. They must spend more money on scientific

medicine. Looss has very poor accommodations. The laboratories are good,

but the staffs are very insufficient. The hospital is impossible. I am

brown as a fellah—such sun—a blaze all day. We reached Cairo in one of

those sand storms, the air filled with a greyish dust which covers

everything and is most irritating to eyes and tubes. This boat is

delightful—five—six miles an hour against the current, which is often

very rapid. The river gets very shallow at this season, and is fully

eighteen feet below flood level. I have been reading Herodutus, who is

the chief authority now on the ancient history of Egypt. He seems to

have told all of the truth he could get and it has been verified of late

years in the most interesting way. Tomorrow we start at 8 for the Tombs

of Denderah—a donkey ride of an hour. We are tied up to one of Cook’s

floating barge docks,squatted out side is a group of natives and the

Egyptian policeman (who is in evidence at each stopping-place) is

parading with an old Snider and a fine stock of cartridges in his belt.

P. S. 24th. Have just seen Denderah and the Temple of Hathor. Heavens,

what feeble pigmies we are! Even with steam, electricity and the Panama

Canal.

What fun to travel with a spirit like this, and he rarely went anywhere

without having two or three youngsters on his trail. The summer his

Oxford decision was finally made two of us crossed with him, indeed

shared the same small stateroom, and, as I recall it, were not permitted

to pay our share. We learned something of his methods of work, and had

we not been on this intimate basis he would have appeared to us, as to

the other voyagers, as the most carefree individual aboard. As a matter

of fact he was always the first awake, and we would find him propped up

with pillows reading or writing, and his bunk was so cluttered with

books during the whole trip that there was scant room for its legitimate

occupant. He breakfasted while we dressed, and then went on with his

morning’s work while the rest of us wandered about the deck with good

intentions but usually with an unread book under our arms. At luncheon

he would appear; the remainder of the day was a continuous frolic. We

roped in the ship’s doctor and got up a medical society of the

physicians aboard. I find that I have preserved the program which he

arranged.

MEDICO-NAUTICAL STUDIES

By Members of the North Atlantic Medical Society

Edited by Du. Fkancis Vekdon of S. S. “Campania”

Perpetual President

The volume containing

about seven hundred pages will be issued from the Utopian Press, Thos.

More & Sons, Atlantis. Price £1.

I. A study of the ‘sea-change’ mentioned in the “Tempest” as a key to

the Shakespeare-Baconian controversy

II. The minimal lymph pressure in the ampullae as a cause of

sea-sickness

III. The otoconial rattle in sea sickness. A study in aural ausculatory

physics

IV. On Broadbent's theory of steady dextral cerulean vision as a

preventative in the disease

V. A demonstration of the centripedal course of the neuro-electrical

vagal waves of Rosenbach, with ten charts

VI. A comprehensive investigation on marine phosphenes with their

relation to latitude and longitude

VII. A statistical inquiry into the sequelae of sea-sickness in ten

thousand consecutive cases treated successfully with specifics

VIII. On the chemistry of aquaverdin. A new gastro-cu-taneous sea

pigment

IX. A comparative study of the effects of prolonged seasickness on (1)

drinkers (2) abstainers

X. The aesthetics of sea-sickness, with six photo-grav-ures from

sketches by Sargent and Abbey

XI. Salt as the cause of appendicitis—results of a collective

investigation showing the extraordinary frequency of the disease after

sea voyages

XII. A sociological inquiry upon the influence of sea travel on the

birth rate of different communities

All this was doubtless very frivolous but he spent no idle hours, and

getting enjoyment out of trifles at the proper time and making others

participate was as characteristic of the man as his hours of industry

when sitting down to the day’s work.

Few scholars have received more recognition for their work, few have

received so many honors nor carried them so well. With it all he

preached and practiced humility. To quote from one of the essays in “Aequinimitas”:

“In these days of aggressive self-assertion, when the stress of

competition is so keen and the desire to make the most of oneself so

universal it may seem a little old-fashioned to preach the necessity of

this virtue, but I insist for its own sake, and for the sake of what it

brings, that a due humility should take the place of honour on the

list.”

His charm as a writer had much to do with his great success as a

teacher, and his bibliography, covering a period of 49 years, is most

extensive—730 titles, including his collected essays and addresses,

having been assembled by Miss Blogg in commemoration of his last

birthday. There is a great range of subjects beside those pertaining to

medicine and medical history. His “TextBook of Medicine,” of which

nearly 200,000 copies have been printed, kept con-stantlyiunder

revision, translated into French, German, Spanish and Chinese and now

entering on its ninth edition, was written during his early years in

Baltimore and since 1892 has been read—nay devoured— by countless

medical students and graduates alike. It remains probably the most used

and most useful book in medicine today.

As is well known, his attachment to young men and his fondness for

literary allusion once got him into trouble by a quotation from “The

Fixed Period,” one of Anthony Trollope’s rarer novels, which probably

few have read and which is difficult to obtain, as the present writer

knows to his cost. Thus the remark about chloroform, really Trollope’s,

was made in the course of his farewell address to his devoted Baltimore

colleagues and friends, many of whom were over 60, an age he was

approaching himself. And he would have been the last to have offended

them. It was an address full of deep feeling for all that he was soon to

leave behind, but the representatives of the press who were present

singled out this one remark to be headlined. The sad feature of this

episode is that it stands as one of the best examples of the

heartlessness of the press when an opportunity offers itself for copy,

no matter who may be sacrificed. On the eve of his departure from

America the notoriety probably hurt him considerably, though he wisely

made no reply, not even at the great banquet which was given him at the

time by the profession of the country, on which occasion Weir Mitchell

presented him with the rare Franklin imprint of Cicero’s “De Senectute.”

He knew when to keep his tongue as with a bridle.

His IngersoII Lecture on “Science and Immortality” is a good example of

his charming literary style, and there is an interesting story of how he

came to accept the lectureship, which others must tell. It was given

late in 1904, a few months before his transference to Oxford, when he

was in great demand everywhere and by everyone and could find no time

for its preparation. Finally, a few days before the date of the

occasion, he slipped away one night to New York, hid in the University

Club, and wrote the lecture in a single morning. It is so full of

allusion that to appreciate it fully one must read it with the Bible in

one hand, the “Religio Medici” in the other, and “In Memoriam” near by.

In this he gives his own confession to the effect that, as Cicero

had once said, he would rather be mistaken with Plato than be in the

right with those who deny altogether the life after death.

At seventy in the forefront of activities innumerable, of unusual

physical vigor and buoyancy, coming of a long-lived race, William

Osier’s death may be regarded as a consequence of the war. No human

being loathed strife more than he; few had been as successful in

avoiding it in any guise. This characteristic made him suffer unduly

from the very outbreak of the conflict. He nevertheless threw himself

into it with characteristic energy in connection with the War Office, on

committees, in hospitals, and as a senior consultant to the Forces he

received a Colonel’s commission. The British reply to the famous German

professional note issued early in the war was, I believe, written by him

and shows the man’s spirit and, as always, his charity. The opening and

closing paragraphs may be quoted:

We see with regret the names of many German professors and men of

science, whom we regard with respect and, in some cases, with personal

friendship, appended to a denunciation of Great Britain so utterly

baseless that we can hardly believe that it expresses their spontaneous

or considered opinion. We do not question for a moment their personal

sincerity when they express their horror of War and their zeal for “the

achievements of culture.” Yet we are bound to point out that a very

different view of War, and of national aggrandizement based on the

threat of War, has been advocated by such influential writers as

Nietzsche, von Treitschke, von Biilow, and von Bernhardi, and has

received widespread support from the press and from public opinion in

Germany. This has not occurred, and in our judgment would scarcely be

possible, in any other civilized country. We must also remark that it is

German armies alone which have, at the present time, deliberately

destroyed or bombarded such monuments of human culture as the Library at

Louvain and the Cathedrals at Rheims and Malines. No doubt it is hard

for human beings to weigh justly their country’s quarrels; perhaps

particularly hard for Germans, who have been reared in an atmosphere of

devotion to their Kaiser and his army, who are feeling acutely at the

present hour, and who live under a Government which, we believe, does

not allow them to know the truth. Yet it is the duty of learned men to

make sure of their facts.

The German professors appear to think that Germany has, in this matter,

some considerable body of sympathizers in the Universities of Great

Britain. They are gravely mistaken. Never within our lifetime has this

country been so united on any great political issue. We ourselves have a

real and deep admiration for German scholarship and science. We have

many ties with Germany, ties of comradeship, of respect, and of

affection. We grieve profoundly that, under the baleful influence of a

military system and its lawless dreams of conquest, she whom we once

honoured now stands revealed as the common enemy of Europe and of all

peoples which respect the Law of Nations. We must carry on the war on

which we have entered. For us, as for Belgium, it is a war of defence,

waged for liberty and peace.

His only child, Revere, an Oxford undergraduate and his father’s devoted

playmate, who too hated strife, on coming of military age underwent

training as a field artillery officer, was commissioned Lieutenant,

served with his battery with great credit for a year in France, and was

mortally wounded in action September 2, 1917, in the Ypres salient. Thus

the great grandson of our Paul Revere who roused Lexington and Concord

lies under a wooden cross in Flanders in the corner of a foreign field

that is forever England. By a strange coincidence, a group of American

officers, who knew what grief this would bring, were there to bare their

heads at his Last Post.

From this loss, particularly heartrending to one of his nature, his

father never fully recovered. Though unchanged in his outward dealings

with people and affairs, he suffered much from insomnia and his health

was so undermined that he became an easy prey to an old enemy, bronchial

attacks. He finally contracted pneumonia and died suddenly on December

29th from one of its complications which had made an operation

necessary.

At the time of the farewell dinner in New York in 1905, Dr. Osier

confessed under the emotion of his reply to the tribute that had been

paid him, that to few men had happiness come in so many forms as it had

come to him; that his three personal ideals had been, to do the day’s

work well, to act the Golden Rule in so far as in him lay, and lastly to

cultivate such a measure of equanimity as would enable him to bear

success with humility, the affection of his friends without pride, and

to be ready when the day of sorrow and grief came to meet it with the

courage befitting a man.

During these last two years, though he must have felt at times, as did

his anxious friends, that possibly his span was run, his spirit was

unflagging. His son, though essentially an out-of-doors boy, through

living in an atmosphere of books acquired biblio-philic tastes of his

own and had formed, like Harry Widener at Harvard and Alexander Cochrane

at Yale a valuable collection of imprints of the Tudor and Stewart

periods. To this collection, Sir William subsequently made many

additions from his own carefully chosen books and manuscripts. He and

Lady Osier presented the collection to the Johns Hopkins undergraduates

as a memorial to their son, to become something like the Elizabethan

Club at Yale, a rallying point for young college men with literary and

bookloving tendencies. He worked, too, at every odd moment to complete,

so far as possible, the unique catalogue of his own lifetime collection

of treasures relating to the history and literature of medicine, ranging

from a medical tablet from Sardanapolis through a series of priceless

manuscripts and incunabulas to the essential contributions to medicine

in their originals of our own time.

This incomparable collection with its elaborate catalogue, which is not

a mere enumeration of volumes but is largely biographical, indeed

autobiographical in character, is destined for the library of McGill,

where he held his first chair in medicine. Sir William as may not be

generally known had lately been offered but had refused the position as

the head of that great Canadian university. He also received a year ago

the amazing offer from both political parties that he stand as fusion

candidate for the Oxford seat in Parliament, but refused on the ground

that it should in justice be offered to Asquith.

As President of the Classical Association, one of his most notable and,

so far as I know, his last address, on “The Old Humanities and the New

Sciences” was given before that body in Oxford, May 16th, 1919. That a

scientist and physician should become president of the most eminent

group of British scholars, whose aim is to “promote the development and

maintain the well-being of classical studies” would seem incongruous did

one not know the man whose Greek Testament always stood by the “Religio

Medici” at his bedside. Disclaiming that he had “ever by pen or tongue

suggested the possession of even the traditional small Latin and Ie^s

Greek,” in this remarkable address given in his most brilliant style he

makes a pica for no human letters without natural science and no science

without human letters.

It was inevitable that the address should be colored by frequent

allusions to the war and appeals for individual service to the

community. Quoting Plato’s “Republic” that“ States are as the men are,

they grow out of human characters,” he concludes with this paragraph:

With the hot blasts of hate still on our cheeks, it may seem a mockery

to speak of this as the saving asset in our future; but is it not the

very marrow of the teaching in which we have been brought up? At last

the gospel of the right to live, and the right to live healthy, happy

lives, has sunk deep into the hearts of the people; and before the war,

so great was the work of science in preventing untimely death that the

day of Isaiah seemed at hand “when a man’s life should be more precious

than fine gold, even a man than the gold of Ophir.” There is a sentence

in the writings of the Father of Medicine upon which all commentators

have lingered, rjv yap Traprj <f>i\av6puTrit), Trapeari nal 'iXorexvi' —

the love of humanity associated with the love of his craft!—philanthropia

and philotechnia—the joy of working joined in each one to a true love of

his brother. Memorable sentence indeed, in which for the first time was

coined the magic word philanthropy, and conveying the subtle suggestion

that perhaps in this combination the longings of humanity may find their

solution, and Wisdom—philosophia —at last be justified of her children.

Two of Osier’s lay sermons to students have been published, in which his

own life habits are more or less reflected. In one of them given at Yale

where he was giving the Silliman Lectures in 1913, he offered “his

fellow students” a way of life—“a path in which the wayfaring man cannot

err, a life in day-tight compartments, the main business of which is not

to see dimly at a distance, but to do what lies clearly at hand.”

In 1910 “Man’s Redemption of Man” was delivered at a service for the

students at the University of Edinburgh. Osier unconsciously chose as

his text from Isaiah what he himself has been to those who knew him.

And a man shall be as an hiding-place from the wind, and a covert from

the tempest; as rivers of water in a dry place; as the shadow of a great

rock in a weary land.

You can also read the book...

The Great

Physician, Sir William Osler

By Edith Gittings Reid (1931) |