|

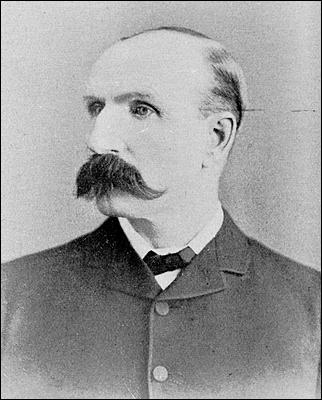

Robert G. Reid (1842-1908)

Reid emigrated to Canada in 1871.

From Henry Youmans Mott, Newfoundland Men (Concord, N.H.: Cragg, 1894)

REID, Sir ROBERT GILLESPIE, railway

contractor; b. 12 Oct. 1842 in Coupar Angus, Scotland, son of William

Robertson Reid and Catherine Gillespie; m. 17 Aug. 1865 Harriet Duff in

Auckland, New Zealand, and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 3

June 1908 in Montreal.

Robert Reid’s father owned a linen mill at Coupar Angus. After leaving

school Robert was apprenticed to an uncle, a stonemason at nearby Leys

of Hallyburton. He worked as a mason in the area of his home town for a

few years, and then emigrated to Australia to prospect for gold in 1865,

meeting his future wife during the passage. The gold-rush had passed its

peak by this time and Reid found that prospecting was not so lucrative

as he had hoped. A partnership to work a claim did not pan out and he

turned to practising his trade, finding his skills in demand on public

works in New South Wales. Eventually he began working on the

construction of stone viaducts in the Blue Mountains there, thus

initiating his involvement with railway construction.

Reid returned to Coupar Angus in 1869, presumably to take on some role

in the family business, his father having died in 1867. In 1871 he

emigrated once again – without his young family – to North America. In

all likelihood he was looking for opportunities in railway construction

and, although he travelled first to New York, he soon concluded that

there was greater promise in Canada, perhaps on the understanding that

construction of a transcontinental railway was imminent. He went on to

Ottawa, where according to family tradition his first job involved stone

work on an extension to the Parliament Buildings. In 1872 he was working

on masonry abutments for the Grand Trunk Railway’s International Bridge

between Fort Erie, Ont., and Buffalo, N.Y., completed in 1873 [see Sir

Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski*]. He brought out his family from Scotland in

that year and took up residence in Galt (Cambridge), Ont., where he

formed a partnership with the contractor James Isbester. For the next

few years, as the “outside man” of Isbester and Reid, he worked on

subcontracts with the Grand Trunk in Canada and the United States, and

then on bridges along the Ottawa River for the Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa

and Occidental Railway.

In the late 1870s Reid moved to the United States, to work in

construction of the American trans-continentals. He apparently

established his family in California, although for the next five years

he was employed chiefly in Texas. In 1880 Reid worked on bridges for the

Southern Pacific, including a bridging of the Colorado River at Austin

which gave him a reputation for being able to overcome difficult

geographical obstacles within budget. In 1882 he subcontracted to build

iron and masonry bridges for 250 miles of the International line, west

of San Antonio and into Mexico, among them a bridge over the Rio Grande.

The next year he finished a railway bridge over the Delaware Water Gap,

N.J.–Pa. It is reported that this contract solidified his reputation as

a bridge contractor of uncommon ability and especially as a man who

stuck to his word. Despite having been brought into the project after

work had commenced, and despite being abandoned by the original

contractor when it became apparent that the contract would not cover the

costs of construction, Reid completed the bridge.

His reputation now established, Reid returned to Canada late in 1883. He

had retained at least some connections among Canadian railwaymen, and he

may have been actively recruited by the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Whatever the case, he was quickly entrusted with some of the CPR’s most

difficult subcontracts, building bridges along the north shore of Lake

Superior. Reid’s work would appear to have been exemplary, and it earned

him the lasting trust of William Cornelius Van Horne*, then

vice-president of the CPR, and most especially of Van Horne’s assistant

Thomas George Shaughnessy*, who became a lifelong friend. His

achievements included the near-legendary Jackfish Bay section of the

line, which necessitated the most difficult network of tunnels and

bridges east of the Rockies.

Reid’s work commanded respect both for his abilities and for his

propriety in financial matters and led to a contract, reputedly without

a tender, to work on the Lachine Bridge, near Montreal; it was completed

in 1886. By this time he had taken up residence in Montreal. Then, in

1887, Reid began a contract in Ontario to complete the Sudbury branch of

the CPR, an 86-mile line from Algoma Mills (Algoma) to Sault Ste Marie.

This was a milestone in Reid’s career: it was his first contract to

construct a railway line and it was the first time he was joined by his

eldest son, William Duff*, who was increasingly to become the “outside

man” for his father. In that year as well he and Isbester undertook to

build the foundations of a bridge at Grand Narrows, Cape Breton, and a

46-mile stretch of the Intercolonial Railway between the narrows and

Point Tupper, near Port Hawkesbury; both were completed in 1890. Reid

contracted the “inflammatory rheumatism” that was to plague him for the

rest of his life while standing in Bras d’Or Lake to oversee a critical

stage in the construction of the bridge.

Although by 1890 Reid had made a substantial fortune in railway

contracting, it is for his work in building the railway across

Newfoundland that he is chiefly known. On 16 June that year, as the

Grand Narrows Bridge was being completed, he and George Hodgson

Middleton signed an agreement with the government of Sir William

Vallance Whiteway to take over construction of the main line from

Harbour Grace Junction (Whitbourne) to Halls Bay. Reid’s involvement was

welcomed in Newfoundland since he was personally wealthy and well

connected (letters of recommendation had come from Van Horne and

engineers Sandford Fleming* and Collingwood Schreiber*). Construction of

the railway had been floundering for nearly a decade: the original

contractor had gone into receivership after completing an 84-mile line

from St John’s to Harbour Grace and the government had constructed a

26-mile branch line to Placentia as a public work.

Reid and Middleton contracted to build the 261 miles from Harbour Grace

Junction to Halls Bay within five years for $15,600 per mile – Reid was

willing to accept Newfoundland government bonds as payment – and agreed

to operate the Placentia branch without subsidy. This project was

decidedly the largest that Reid had taken on and the first that he was

unable to oversee at every stage. By this time, however, he had a number

of trusted employees, many of them Perthshire Scots who had worked under

him in Canada. His sons, particularly William (known in Newfoundland as

W.D.), also increasingly involved themselves in construction. Reid

became, for the first time, the “inside man,” based in Montreal. He

rarely visited Newfoundland except in the summers and usually wintered

in California after 1890.

Although construction was progressing satisfactorily, in May 1892 Reid

and Middleton broke their connection for “personal reasons” and Reid

agreed to fulfil the contract. As the line neared completion the

Whiteway government decided to continue it to Port aux Basques

(Channel–Port aux Basques), abandoning the idea of a terminus at Halls

Bay. In May 1893 Reid contracted to complete the line – to be known as

the Newfoundland Northern and Western Railway – within three years on

the same terms, and to operate it for ten years in return for grants of

5,000 acres of land per mile operated.

Early in 1894, 17 members of the House of Assembly were accused under

the Corrupt Practices Act and the Whiteway government fell. The ensuing

political uncertainty led Reid to suspend construction, since his

railway bonds had become unsaleable. The political situation, coupled

with several years of poor fisheries and the feeling in world financial

markets that Newfoundland had overextended itself in its eagerness to

have a railway built, contributed to a bank crash in December [see James

Goodfellow*].

Reid became more active in the affairs of the colony when it appeared

that the government might have to default in the aftermath of these

developments. Whiteway returned to power in February 1895, and Reid

encouraged a delegation to Ottawa to seek confederation with Canada and

also helped bring his bankers, the Bank of Montreal, into Newfoundland

to sort out the mess left by the collapse of the banks. His contacts in

the Montreal financial community enabled Colonial Secretary Robert Bond*

to arrange a loan which avoided a default, and construction of the

railway resumed in June. As the line approached Port aux Basques in 1897

Reid commissioned the construction of a steamship, the Bruce, to connect

the Newfoundland with Canadian rail lines, thus beginning his

involvement with coastal shipping.

In the spring of 1897 the Whiteway government had begun to anticipate a

general election and the completion of the main line, which was sure to

bring widespread unemployment. The government then contracted with Reid

to build three branch lines. The act authorizing construction also

empowered the government to make another contract in order to

consolidate the railway system under a single operator. After Whiteway’s

party lost the election of October 1897, Reid began to negotiate with

the new prime minister, James Spearman Winter*, and his minister of

finance, Alfred Bishop Morine*, for an agreement to extend his operating

contract beyond 1903. The railway contract of 1898 made provision for

Reid to operate the main line for 50 years in return for a further grant

of 5,000 acres of land per mile. He also undertook to operate the

Newfoundland coastal steamer service with a government subsidy and take

over operation of – and eventually purchase – the government telegraph

line [see Alexander McLellan Mackay]. In return for an immediate payment

of $1,000,000 and the future reversion of a portion of Reid’s lands the

government agreed that after 50 years the railway was to become the

property of Reid’s successors.

The contract, introduced into the legislature on 28 Feb. 1898, passed

quickly and was signed on 15 March. Governor Sir Herbert Harley Murray

had at first sought to withhold royal assent but was instructed to sign

by British colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain in a dispatch dated 23

March. However, Chamberlain’s instructions also included a strong

statement questioning the wisdom of the contract, for local publication:

“Practically all the Crown Lands of any value become . . . the freehold

property of a single individual. . . . Such an abdication by a

Government of some of its most important functions is without parallel.

. . . The Colony is divested for ever of any control over or power of

influencing its own development.” The contract became the more

controversial after it was learned in November that finance minister

Morine had been on retainer as Reid’s solicitor during the negotiations.

A significant faction of the Liberal opposition (led by Edward Patrick

Morris*) had voted for the contract, but Bond, now Liberal leader, was

able to use the uproar over Morine’s role and the opposition of the

Colonial Office to unite his party against the Conservatives.

Early in 1900 Reid and Morine were in London attempting to raise

£1,000,000 to develop Reid’s properties when the Winter government fell.

Upon returning to Newfoundland Reid applied to the new Bond government

to have the 1898 contract assigned to a limited liability company,

having learned that British financial backing to develop his lands would

not be forthcoming as long as the “Reid empire” remained a sole

proprietorship. Bond refused. After a November general election in which

the Conservatives, led by Morine and financed by Reid, were trounced by

Bond’s Liberals, Reid agreed to renegotiate the contract. A new one was

signed on 2 Aug. 1901. The government resumed full ownership of the

railway and telegraph, after paying back Reid’s $1,000,000 plus

interest, and submitted the question of his losses on the operation of

the telegraph to arbitration. Reid also returned 1.5 million acres of

land to the crown in exchange for $850,000.

By this time Reid had turned virtually all of the day-to-day management

of affairs to his sons – indeed, William had negotiated the 1898

contract while his father wintered in California. In fact, it appears

that the impetus for this contract had come in part from Reid’s sons,

who wished to get out of the railway business and make their own

fortunes by exploiting the resources of the Reid lands. The founder

remained president of the Reid Newfoundland Company until his death,

although he felt the plan to develop its lands had been irretrievably

damaged by the renegotiation of the 1898 contract.

From the signing of the 1898 contract Reid ceased to be as favourably

regarded in Newfoundland. For the remainder of his life the government

was in the hands of Bond, and the premier developed an increasing

dislike for the Reids (most particularly William, who schemed to bring

about Bond’s removal). It seems likely that Reid strongly disapproved of

the participation of his son and Morine in the 1904 Conservative

election campaign, for he had issued a directive that railway employees

were to refrain from becoming involved in politics. Although he was, for

the most part, removed from Newfoundland affairs, the Liberals portrayed

him as “Czar Reid” and built their popular support at his expense. His

residence remained in Montreal, where he was a director of the CPR

(after 1903), the Royal Trust Company, and the Bank of Montreal. In 1905

Reid offered to sell all his Newfoundland holdings to the government for

$9.5 million, or just his interest in the railway and steamships for

$3.5 million, because he felt that animosity towards the Reid

Newfoundland Company was making its continued operation of the railway

unworkable and hindering the development of its lands. Bond refused to

consider the offer.

Reid did not make his customary summer visit to Newfoundland in 1906,

his health having deteriorated to the point where he was unable to walk.

He was knighted in the New Year’s honours list of 1907 and made his last

visit to Newfoundland that summer. He died of pneumonia at his home in

Montreal on 3 June 1908. As his funeral was taking place there on 6

June, shops in St John’s were closed for a half hour, and the railway

and steamships ceased operation for 15 minutes.

Reid’s will directed that his interest in the Reid Newfoundland Company

was to be “realized and disposed of as soon as possible” and advised his

heirs not to “invest any part of my estate in any new enterprise or in

any speculative or Hazardous investments in Newfoundland or elsewhere.”

His family, however, would continue to operate the Newfoundland railway

until 1923, and the Reid Newfoundland Company was to manage the Reid

lands until they were purchased by the provincial government in the

1970s.

By all accounts Robert Gillespie Reid was a competent contractor,

taciturn and scrupulous in an age when railway contractors were not

particularly noted for such qualities. The work for which he is best

known, the building of the Newfoundland railway, came after the most

active stage of his career had passed. Yet, the line across Newfoundland

was very much the achievement of his will and ability. In Newfoundland

questionable motives and high-handed political tactics later became

associated with the name Reid, but these may be in large part attributed

to his sons, and particularly the mercurial William.

Robert Cuff |