A young Highlander—To rival Hearne—Fort

Chipewyan built— French Canadian voyageurs—Trader Leroux—Perils

of the route —Post erected on Arctic Coast—Return

journey—Pond's miscalculations—Hudson Bay Turner—Roderick

McKenzie's hospitality —Alexander Mackenzie—Astronomy and

mathematics—Winters on Peace River—Terrific journey—The

Pacific slope—Dangerous Indians—Pacific Ocean,

1793—North-West passage by land— Great achievement—A notable

book.

One of

the chiefs of the fur traders seems to have had a higher

ambition than simply to carry back to Grand Portage canoes

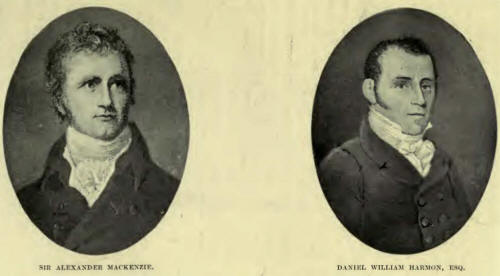

overflowing with furs. Alexander Mackenzie had the restless

spirit that made him a very uncertain partner in the great

schemes of McTavish, Frobisher & Co., and led him to seek

for glory in the task of exploration. Coming as a young

Highlander to Montreal, he had early been so appreciated for

his ability as to be sent by Gregory, McLood & Co. to

conduct their enterprise in Detroit. Then we have seen that,

refusing to enter the McTavish Company, he had gone to

Churchill River for the Gregory Company. The sudden union of

all the Montreal Companies (1787) caused, as already noted,

by Pond's murder of Ross, led to Alexander Mackenzie being

placed in charge in that year of the department of

Athabasca. The longed-for opportunity had now come to

Mackenzie. He hoard from the Indians and others of how

Samuel Hearne, less than twenty years before, on behalf of

their great rivals, the Hudson's Bay Company, had returned

by way of Lake Athabasca from his discovery of the

Coppermine River. Ho longed to reach the Arctic Sea by

another river of which he had heard, and eclipse the

discovery of his rival. He even had it in view to seek the

Pacific Ocean, of which he was constantly hearing from the

Indians, where white men wearing armour were to be met—no

doubt meaning the Spaniards,

Mackenzie proceeded in a very deliberate way to prepare for

his long journey. Having this expedition in view, he secured

the appointment of his cousin, Roderick McKenzie, to his own

department. Reaching Lake Athabasca, Roderick McKenzie

selected a promontory running out some three miles into the

lake, and here built (1788) Fort Chipewyan, it being called

from the Indians who chiefly frequented the district. It

became the most important fort of the north country, being

at the converging point of trade on the great watercourses

of the north-west.

On June

3rd, 1789, Alexander Mackenzie started on his first

exploration. In his own birch-bark canoe was a crew of

seven. His crew is worthy of being particularized. It

consisted of four French Canadians, with the wives of two of

them. These voyageurs were Francois Barrieau, Charles

Ducette, or Cadien, Joseph Landry, or Cadien, Pierre de

Lorme. To complete the number was John Steinbruck, a German.

The second canoe contained the guide of the expedition, an

Indian, called the "English chief," who was a great trader,

and had frequented year by year the route to the English, on

Hudson Bay. In his canoe were his two wives, and two young

Indians. In a third canoe was trader Leroux, who was to

accompany the explorer as far north as Slave Lake, and

dispose of the goods he took for furs. Leroux was under

orders from his chief to build a fort on Slave Lake.

Starting on June 3rd, the party left

the lake, finding their way down Slave River, which they

already knew. Day after day they Journeyed, suffered from

myriads of mosquitoes, passed the steep mountain portage,

and, undergoing many hardships, reached Slave Lake in nine

days.

Skirting the lake, they departed

north by an unknown river. This was the object of

Mackenzie's search. Floating down the stream, the Horn

Mountains were seen, portage after portage was crossed, the

mouth of the foaming Great Slave Lake River was passed, the

snowy mountains came in view in the distance, and the party,

undeterred, pressed forward on their voyage of discovery.

The usual incidents of early travel

were experienced. The accidents, though not serious, were

numerous ; the scenes met with were all new ; the natives

were surprised at the bearded stranger ; the usual deception

and fickleness were displayed by the Indians, only to be

overcome by the firmness and tact of Mackenzie; and forty

days after starting, the expedition looked out upon the

floating ice of the Arctic Ocean. Mackenzie, on the morning

of July 14th, erected a post on the shore, on which he

engraved the latitude of the place (69 deg. 14' N.), his own

name, the number of persons in the party, and the time they

remained there.

His object

having been thus accomplished, the important matter was to

reach Lake Athabasca in the remaining days of the open

season. The return journey had the usual experiences, and on

August 24th they came upon Leroux on Slave Lake, where that

trader had erected Fort Providence. On September 12th the

expedition arrived safely at Fort Chipe-wyan, the time of

absence having been 102 days. The story of this journey is

given in a graphic and unaffected manner by Mackenzie in his

work of 1801, but no mention is made of his own name being

attached to the river which he had discovered.

We have stated that Peter Pond had

prepared a map of the north country, with the purpose of

presenting it to the Empress of Russia. Being a man of great

energy, he was not deterred from this undertaking by the

fact that he had no knowledge of astronomical instruments

and little of the art of map-making. His statements were

made on the basis of reports from the Indians, whose custom

was always to make the leagues short, that they might boast

of the length of their Journeys. Computing in this way, he

made Lake Athabasca so far from Hudson Bay and the Grand

Portage that, taking Captain Cook's observations on the

Pacific Coast four years before this, the lake was only,

according to his calculations, a hundred or a hundred and

fifty miles from the Pacific Ocean.

The effect of Pond's calculations,

which became known in the Treaty of Paris, was to stimulate

the Hudson's Bay Company to follow up Hearne's discoveries

and to explore the country west of Lake Athabasca. They

attempted this in 1785, but they sent out a boy of fifteen,

named George Charles, who had been one year at a

mathematical school, and had never made there more than

simple observations. As was to have been expected, the boy

proved incompetent. Urged on by the Colonial Office, they

again in 1791 organized an expedition to send Astronomer

Philip to Turner to make the western journey. Unaccustomed

to the Far West, and poorly provided for this journey,

Turner found himself at Fort Chipewyan entirely dependent

for help and shelter on the Nor'-Westers. He was, however,

qualified for his work, and made correct observations, which

settled the question of the distance of the Pacific Ocean.

Mr. Roderick McKenzie showed him every hospitality. This

expedition served at least to show that the Pacific was

certainly five times the distance from Lake Athabasca that

Pond had estimated.

After

coming back from the Arctic Sea, Alexander Mackenzie spent

his time in urging forward the business of the fur trade,

especially north of Lake Athabasca; but there was burning in

his breast the desire to be the discoverer of the Western

Sea. The voyage of Turner made him still more desirous of

going to the West.

Like

Hearne, Alexander Mackenzie had found the want of

astronomical knowledge and the lack of suitable instruments

a great drawback in determining his whereabouts from day to

day. With remarkable energy, he, in the year 1791, journeyed

eastward to Canada, crossed the Atlantic Ocean to London,

and spent the winter in acquiring the requisite mathematical

knowledge and a sufficient acquaintance with instruments to

enable him to take observations.

He was now prepared to make his journey

to the Pacific Ocean. He states that the courage of his

party had been kept up on their reaching the Arctic Sea, by

the thought that they were approaching the Mer de l'Ouest,

which, it will be remembered, Verendrye had sought with such

passionate desire.

In the very

year in which Mackenzie returned from Great Britain, his

great purpose to reach the Pacific Coast led him to make his

preparations in the autumn, and on October 10th, 1792, to

leave Fort Chipewyan and proceed as far up Peace River as

the farthest settlement, and there winter, to be ready for

an early start in the following spring. On his way he

overtook Mr. Finlay, the younger, and called upon him in his

camp near the fort, where he was to trade for the winter.

Leaving Mr. Finlay "under several volleys of musketry."

Mackenzie pushed on and reached the spot where the men had

been despatched in the preceding spring to square timber for

a house and cut palisades to fortify it. Here, where the

Boncave joins the main branch of the Peace River, the fort

was erected. His own house was not ready for occupation

before December 23rd, and the body of the men went on after

that date to erect five houses for which the material had

been prepared. Troubles were plentiful; such as the

quarrelsomeness of the natives, the killing of an Indian,

and in the latter part of the winter severe cold. In May,

Mackenzie despatched six canoes laden with furs for Fort

Chipewyan.

The somewhat cool

reception that Mackenzie had received from the other

partners at Grand Portage, when on a former occasion he had

given an account of his voyage to the Arctic Sea, led him to

be doubtful whether his confreres would fully approve the

great expedition on which ho was determined to go. He was

comparatively a young man, and he knew that there were many

of the traders jealous of him. Still, his determined

character led him to hold to his plan, and his great energy

urged him to make a name for himself.

Mackenzie had found much difficulty in

securing guides and voyageurs. The trip proposed was so

difficult that the bravest shrank from it. The explorer had,

however, great confidence in his colleague, Alexander

Mackay, who had arrived at the Forks a few weeks before the

departure. Mackay was a most experienced and shrewd man.

After faithfully serving his Company, he entered, as we

shall see, the Astor Fur Company in 1811, and was killed

among the first in the fierce attack on the ship Tonquin,

which was captured by the natives. Mackenzie's crew was the

best he could obtain, and their names have become historic.

There were besides Mackay, Joseph Landry and Charles Ducette,

two voyageurs of the former expedition, Baptiste Bisson,

Francois Courtois, Jacques Beauchamp, and Francois Beaulieu,

the last of whom died so late as 1872, aged nearly one

hundred years, probably the oldest man in the North-West at

the time. Archbishop Taché gives an interesting account of

Beaulieu's baptism at the age of seventy. Two Indians

completed the party, one of whom had been so idle a lad,

that he bore till his dying day the unenviable name of "Cancre"—the

crab.

Having taken, on the day

of his departure, the latitude and longitude of his winter

post, Mackenzie started on May 9th, 1793, for his notable

voyage. Seeing on the banks of the river elk, buffalo, and

bear, the expedition pushed ahead, meeting the difficulties

of navigation with patience and skill. The murmurs of his

men and the desire to turn back made no impression on

Mackenzie, who, now that his Highland blood was up,

determined to see the journey through. The difficulties of

navigation became extreme, and at times the canoes had to be

drawn up stream by the branches of trees.

At length in longitude 121° W.

Mackenzie reached a lake, which he considered the head of

the Ayugal or Peace River. Here the party landed, unloaded

the canoes, and by a portage of half-a-mile on a well-beaten

path, came upon another small lake. From this lake the

explorers followed a small river, and here the guide

deserted the party. On June 17th the members of the

expedition enjoyed, after all their toil and anxiety, the

"inexpressible satisfaction of finding themselves on the

bank of a navigable river on the west side of the first

great range of mountains."

Running rapids, breaking canoes, re-ascending streams,

quieting discontent, building new canoes, disturbing tribes

of surprised Indians, and urging on his discouraged band,

Mackenzie persistently kept on his way. He was descending on

Tacoutche Tesse, afterwards known as the Fraser River.

Finding that the distance by this river was too great, he

turned back. At the point where he took this step (June

23rd) was afterwards built Alexandria Fort, named after the

explorer. Leaving the great river, the party crossed the

country to what Mackenzie called the West Road River. For

this land journey, begun on July 4th, the explorers were

provided with food. After sixteen days of a most toilsome

journey, they at length came upon an arm of the sea. The

Indians near the coast seemed very troublesome, but the

courage of Mackenzie never failed him. It was represented to

him that the natives "were as numerous as mosquitoes and of

a very malignant character."

His destination having been reached, the commander mixed up

some vermilion in melted grease and inscribed in large

characters on the south-east face of the rock, on which they

passed the night, "Alexander Mackenzie, from Canada, by land

the twenty-second of July, one thousand seven hundred and

ninety-three."

After a short

rest the well-repaid explorers began their homeward journey.

To ascend the Pacific slope was a toilsome and discouraging

undertaking, but the energy which had enabled them to come

through an unknown road easily led them back by a way that

had now lost its uncertainty. Mackenzie says that when "we

reached the downward current of the Peace River and came in

view of Fort McLeod, we threw out our flag and accompanied

it with a general discharge of firearms, while the men were

in such spirits and made such an active use of their

paddles, that we arrived before the two men whom we left in

the spring could recover their senses to answer us. Thus we

landed at four in the afternoon at the place which we left

in the month of May. In another month (August 24th) Fort

Chipewyan was reached, where the following winter was spent

in trade.

It is hard to

estimate all the obstacles overcome and the great service

rendered in the two voyages of Alexander Mackenzie. Readers

of the "North-West Passage by Land" will remember the

pitiable plight in which Lord Milton and Dr. Cheadle, nearly

seventy years afterwards, reached the coast. Mackenzie's

journey was more difficult, but the advantage lay with the

fur-traders in that they were experts in the matters of

North-West travel. Time and again, Mackenzie's party became

discouraged. When the Pacific slope was reached, and the

voyageurs saw the waters begin to run away from the country

with which they were acquainted, their fears were aroused,

and it was natural that they should bo unwilling to proceed

further.

Mackenzie had, however, all the

instincts of a brave and tactful leader. On one occasion he

was compelled to take a stand and declare that if his party

deserted him, he would go on alone. This at once aroused

their admiration and sympathy, and they offered to follow

him. At the point on the great river where he turned back,

the Indians were exceedingly hostile. His firmness and

perfect self-control showed the same spirit that is found in

all great leaders in dealing with savage or semi-civilized

races. Men like Frontenac, Mackenzie, and General Gordon

seemed to have a charmed life which enabled them to exercise

a species of mesmeric influence over half-trained or

entirely uncultivated minds.

From the wider standpoint, knowledge was supplied as to the

country lying between the two great oceans, and while it did

not, as we know from the voyages seeking a North-West

Passage in this century, lay the grim spectre of an Arctic

channel, yet it was a fulfilment of Verendrye's dream, and

to Alexander Mackenzie, a Canadian bourgeois, a self-made

man, aided by his Scotch and French associates, had come the

happy opportunity of discovering "La Grande Mer de l'Ouest."

Alexander Mackenzie, filled with the

sense of the importance of his discovery, determined to give

it to the world, and spent the winter at Fort Chipewyan in

preparing the material. In this he was much assisted by his

cousin, Roderick McKenzie, to whom he sent the Journal for

revision and improvement. Early in the year 1794, the

distinguished explorer left Lake Athabasca, journeyed over

to Grand Portage, and a year afterward revisited his native

land. He never returned to the "Upper Country," as the

Athabasca region was called, but became one of the agents of

the fur-traders in Montreal, never coming farther toward the

North-west than to be present at the annual gatherings of

the traders at Grand Portage. The veteran explorer continued

in this position till the time when he crossed the Atlantic

and published his well-known "Voyages from Montreal,"

dedicated to "His Most Sacred Majesty George the Third." The

book, while making no pretensions to literary attainment, is

yet a clear, succinct, and valuable account of the fur trade

and his own expeditions. It was the work which excited the

interest of Lord Selkirk in Rupert's Land and which has

become a recognized authority.

In 1801 this work of Alexander

Mackenzie was published, and the order of knighthood was

conferred upon the successful explorer. On his return to

Canada, Sir Alexander engaged in strong opposition to the

North-West Company and became a member of the Legislative

Assembly for Huntingdon County, in Lower Canada. He lived in

Scotland during the last years of his life, and died in the

same year as the Earl of Selkirk, 1820. Thus passed away a

man of independent mind and of the highest distinction. His

name is fixed upon a region that is now coming into greater

notice than ever before.