Royal charters—Good Queen Bess—"So miserable a

wilderness"— Courtly stockholders—Correct spelling—"The nonsense of the

Charters"—Mighty rivers—Lords of the territory—To execute justice—War on

infidels—Power to seize—"Skin for skin"— Friends of the red man.

The

success of the first voyage made by the London merchants to Hudson Bay was

so marked that the way was open for establishing the Company and carrying

on a promising trade. The merchants who had given their names or credit

for Gillam's expedition lost no time in applying, with their patron,

Prince Rupert, at their head, to King Charles II. for a Charter to enable

them more safely to carry out their plans. Their application was, after

some delay, granted on May 2nd, 1670.

The modern method of obtaining privileges such as

they sought would have been by an application to Parliament; but the

seventeenth century was the era of Royal Charters. Much was said in

England eighty years after the giving of this Charter, and again in Canada

forty years ago, against the illegality and unwisdom of such Royal

Charters as the one granted to the Hudson's Bay Company. These criticisms,

while perhaps Just, scarcely cover the ground in question.

As to the abstract point of the granting of Royal

Charters, there would probably be no two opinions to-day, but it was

conceded to be a royal prerogative two centuries ago, although the famous

scene cannot be forgotten where Queen Elizabeth, in allowing many

monopolies which she had granted to be repealed, said in answer to the

Address from the House of Commons: "Never since I was a queen did I put my

pen to any grant but upon pretext and semblance made to me that it was

both good and beneficial to the subject in general, though private profit

to some of my ancient servants who had deserved well. . . Never thought

was cherished in my heart that tended not to my people's good."

The

words, however, of the Imperial Attorney-General and Solicitor-General,

Messrs. Bethel and Keating, of Lincoln's Inn, when appealed to by the

British Parliament, are very wise: "The questions of the validity and

construction of the Hudson's Bay Company Charter cannot be considered

apart from the enjoyment that has been had under it during nearly two

centuries, and the recognition made of the rights of the Company in

various acts, both of the Government and Legislature."

The bestowal of

such great privileges as those given to the Hudson's Bay Company are

easily accounted for in the prevailing idea as to the royal prerogative,

the strong influence at Court in favour of the applicants for the Charter,

and, it may be said, in such opinions as that expressed forty years after

by Oldmixon: "There being no towns or plantations in this country

(Rupert's Land), but two or three forts to defend the factories, we

thought we were at liberty to place it in our book where we pleased, and

were loth to let our history open with the description of so wretched a

Colony. For as rich as the trade to those parts has been or may be, the

way of living is such that we cannot reckon any man happy whose lot is

cast upon this Bay."

The Charter certainly opens with a breath of

unrestrained heartiness on the part of the good-natured King Charles.

First on the list of recipients is "our dear entirely beloved Prince

Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria and Cumberland, etc,"

who seems to have taken the King captive, as if by one of his old charges

when he gained the name of the fiery Rupert of EdgehilL Though the stock

book of the Company has the entry made in favour of Christopher, Duke of

Albemarle, yet the Charter contains that of the famous General Monk, who,

as "Old George," stood his ground in London during the year of the plague

and kept order in the terror-stricken city. The explanation of the

occurrence of the two names is found in the fact that the father died in

the year of the granting of the Charter. The reason for the appearance of

the name of Sir Philip Carteret in the Charter is not so evident, for not

only was Sir George Carteret one of the promoters of the Company, but his

name occurs as one of the Court of Adventurers in the year after the

granting of the Charter. John Portman, citizen and goldsmith of London, is

the only member named who is neither nobleman, knight, nor esquire, but he

would seem to have been very useful to the Company as a man of means.

The Charter states that the eighteen incorporators named deserve the

privileges granted because they "have at their own great cost and charges

undertaken an expedition for Hudson Bay, in the north-west parts of

America, for a discovery of a new passage into the South Sea, and for the

finding of some trade for furs, minerals, and other considerable

commodities, and by such their undertakings, have already made such

discoveries as to encourage them to proceed farther in pursuance of their

said design, by means whereof there may probably arise great advantage to

Us and our kingdoms."

The full name of the Company given in the Charter

is, "The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England, trading into

Hudson Bay." They have usually been called "The Hudson's Bay Company," the

form of the possessive case being kept in the name, though it is usual to

speak of the bay itself as Hudson Bay. The adventurers are given the

powers of possession, succession, and the legal rights and

responsibilities usually bestowed in incorporation, with the power of

adopting a seal or changing the same at their "will and pleasure"; and

this is granted in the elaborate phraseology found in documents of that

period. Full provision is made in the Charter for the election of

Governor, Deputy-Governor, and the Managing Committee of seven. It is

interesting to notice during the long career of the Company how the simple

machinery thus provided was adapted, without amendment, in carrying out

the immense projects of the Company during the two and a quarter centuries

of its existence. The grant was certainly sufficiently comprehensive.

The opponents of the Company in later days mentioned that King Charles

gave away in his sweeping phrase a vast territory of which he had no

conception, and that it was impossible to transfer property which could

not be described. In the case of the English Colonies along the Atlantic

coast it was held by the holders of the charters that the frontage of the

seaboard carried with it the strip of land all the way across the

continent. It will be remembered how, in the settlement with the

Commissioners after the American Revolution, Lord Shelburne spoke of this

theory as the "nonsense of the charters." The Hudson's Bay Company was

always very successful in the maintenance of its claim to the full

privileges of the Charter, and until the time of the surrender of its

territory to Canada kept firm possession of the country from the shore of

Hudson Bay even to the Rocky Mountains.

The generous monarch gave the

Company "the whole trade of all those seas, streights, and bays, rivers,

lakes, creeks, and sounds, in whatsoever latitude they shall be, that lie

within the entrance of the streights commonly called Hudson's Streights,

together with all the lands, countries, and territories upon the coasts

and confines of the seas, streights, bays, lakes, rivers, creeks, and

sounds aforesaid, which are not now actually possessed by any of our

subjects, or by the subjects of any other Christian prince or State."

The wonderful water system by which this great claim was extended over so

vast a portion of the American continent has been often described. The

streams running from near the shore of Lake Superior find their way by

Rainy Lake, Lake of the Woods, and Lake Winnipeg, then by the River

Nelson, to Hudson Bay. Into Lake Winnipeg, which acts as a collecting

basin for the interior, also run the Red River and mighty Saskatchewan,

the latter in some ways rivalling the Mississippi, and springing from the

very heart of the Rocky Mountains. The territory thus drained was all

legitimately covered by the language of the Charter. The tenacious hold of

its vast domain enabled the Company to secure in later years leases of

territory lying beyond it on the Arctic and Pacific slopes. In the grant

thus given perhaps the most troublesome feature was the exclusion, even

from the territory granted, of the portion "possessed by the subjects of

any other Christian prince or State." We shall see afterwards that within

less than twenty years claims were made by the French of a portion of the

country on the south side of the Bay; and also a most strenuous contention

was put forth at a later date for the French explorers, as having first

entered in the territory lying in the basin of the Red and Saskatchewan

Rivers. This claim, indeed, was advanced less than fifty years ago by

Canada as the possessor of the rights once maintained by French Canada.

The grant in general included the trade of the country, but is made more

specific in one of the articles of the Charter, in that "the fisheries

within Hudson's Streights, the minerals, including gold, silver, gems, and

precious stones, shall be possessed by the Company." It is interesting to

note that the country thus vaguely described is recognized as one of the

English "Plantations or Colonies in America," and is called, in compliment

to the popular Prince, "Rupert's Land."

Perhaps the most astounding gift

bestowed by the Charter is not that of the trade, or what might be called,

in the phrase of the old Roman law, the "usufruct," but the transfer of

the vast territory, possibly more than one quarter or a third of the whole

of North America, to hold it "in free and common socage," i.e., as

absolute proprietors. The value of this concession was tested in the early

years of this century, when the Hudson's Bay Company sold to the Earl of

Selkirk a portion of the territory greater in area than the whole of

England and Scotland ; and in this the Company was supported by the

highest legal authorities in England.

To the minds of some, even more

remarkable than the transfer of the ownership of so large a territory was

the conferring upon the Company by the Crown of the power to make laws,

not only for their own forts and plantations, with all their officers and

servants, but having force over all persons upon the lands ceded to them

so absolutely. The authority to administer justice is also given in no

uncertain terms. The officers of the Company "may have power to judge all

persons belonging to the said Governor and Company, or that shall live

under them, in all causes, whether civil or criminal, according to the

laws of this kingdom, and execute justice accordingly." To this was also

added the power of sending those charged with offences to England to be

tried and punished. The authorities, in the course of time, availed

themselves of this right. We shall see in the history of the Red River

Settlement, in the very heart of Rupert's Land, the spectacle of a

community of several thousands of people within a circle having a radius

of fifty miles ruled by Hudson's Bay Company authority, with the customs

duties collected, certain municipal institutions established, and justice

administered, and the people for two generations not possessed of

representative institutions.

One of the powers most jealously guarded by

all governments is the control of military expeditions. There is a settled

unwillingness to allow private individuals to direct or influence them. No

qualms of this sort seem to have been in the royal mind over this matter

in connection with the Hudson's Bay Company. The Company is fully

empowered in the Charter to send ships of war, men, or ammunition into

their plantations, allowed to choose and appoint commanders and officers,

and even to issue them their commissions.

There is a ludicrous ring

about the words empowering the Company to make peace or war with any

prince or people whatsoever that are not Christians, and to be permitted

for this end to build all necessary castles and fortifications. It seems

to have the spirit of the old formula leaving Jews, Turks, and Saracens to

the uncovenanted mercies rather than to breathe the nobler principles of a

Christian land. Surely, seldom before or since has a Company gone forth

thus armed cap-à-pie to win glory and profit for their country.

An

important proviso of the Charter, which was largely a logical sequence of

the power given to possess the wide territory, was the grant of the

"whole, entire, and only Liberty of Trade and Traffick." The claim of a

complete monopoly of trade was held most strenuously by the Company from

the very beginning. The early history of the Company abounds with accounts

of the steps taken to prevent the incoming of interlopers. These were

private traders, some from the English colonies in America, and others

from England, who fitted out expeditions to trade upon the Bay. Full power

was given by the Charter "to seize upon the persons of all such English or

any other subjects, which sail into Hudson's Bay or inhabit in any of the

countries, islands, or territories granted to the said Governor and

Company, without their leave and license in that behalf first had and

obtained." The abstract question of whether such monopoly may rightly be

granted by a free government is a difficult one, and is variously decided

by different authorities. The "free trader " was certainly a person

greatly disliked in the early days of the Company. Frequent allusions are

made in the minutes of the Company, during the first fifty years of its

existence, to the arrest and punishment of servants or employes of the

Company who secreted valuable furs on their homeward voyage for the

purpose of disposing of them. As late as half a century ago, in the more

settled parts of Rupert's Land, on the advice of a judge who had a high

sense of its prerogative, an attempt was made by the Company to prevent

private trading in furs. Very serious local disturbances took place in the

Red River Settlement at that time, but wiser counsels prevailed, and in

the later years of the Company's regime the imperative character of the

right was largely relaxed.

The Charter fittingly closes with a

commendation of the Company by the King to the good offices of all

admirals, justices, mayors, sheriffs, and other officers of the Crown,

enjoining them to give aid, favour, help, and assistance.

With such

extensive powers, the wonder is that the Company bears, on the whole,

after its long career over such an extended area of operations, and among

savage and border people unaccustomed to the restraints of law, so

honourable a record. Being governed by men of high standing, many of them

closely associated with the operations of government at home, it is very

easy to trace how, as "freedom broadened slowly down " from Charles II. to

the present time, the method of dealing with subjects and subordinates

became more and more gentle and considerate. As one reads the minutes of

the Company in the Hudson's Bay House for the first quarter of a century

of its history, the tyrannical spirit, even so far at the removal of

troublesome or unpopular members of the Committee and the treatment of

rivals, is very evident.

This intolerance was of the spirit of the age. In the Restoration, the

Revolution, and the trials of prisoners after rebellion, men were

accustomed to the exercise of the severest penalties for the crimes

committed. As the spirit of more gentle administration of law found its

way into more peaceful times the Company modified its policy.

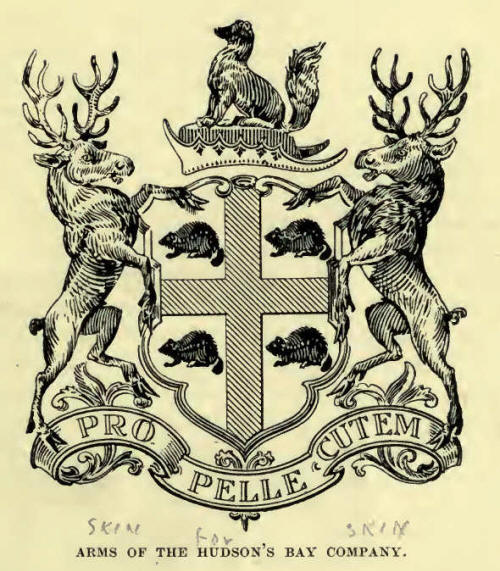

The

Hudson's Bay Company was, it is true, a keen trader, as the motto, "Pro

Pelle Cutem"—"skin for skin"—clearly implies. With this no fault can be

found, the more that its methods were nearly all honourable British

methods. It never forgot the flag that floated over it. One of the

greatest testimonies in its favour was that, when two centuries after its

organization it gave up, except as a purely trading company, its power to

Canada, yet its authority over the wide-spread Indian population of

Rupert's Land was so great, that it was asked by the Canadian Government

to retain one-twentieth of the land of that wide domain as a guarantee of

its assistance in transferring power from the old to the new regime.

The

Indian had in every part of Rupert's Land absolute trust in the good faith

of the Company. To have been the possessor of such absolute powers as

those given by the Charter ; to have on the whole "borne their faculties

so meek"; to have been able to carry on government and trade so long and

so successfully, is not so much a commendation of the royal donor of the

Charter as it is of the clemency and general fairness of the

administration, which entitled it not only officially but also really, to

the title "The Honourable Hudson's Bay Company." |