Old John Jacob

Astor—American Fur Company—The Missouri

Company—A line of posts—Approaches the

Russians—Negotiates with Nor'-Westers—Fails—Four

North-West officials join Astor— Songs of the

voyageurs—True Britishers—Voyage of the

Tonquin —Rollicking Nor'-Westers in Sandwich

Islands—Astoria built— David Thompson

appears—Terrible end of the Tonquin—Aster's

overland expedition—Washington Irving's

"Astoria, a romance" —The Beaver rounds the

Cape—McDougall and his small-pox phial—The

Beaver sails for Canton.

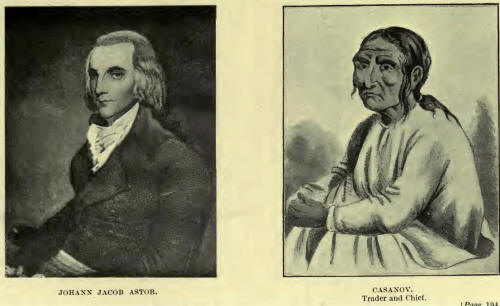

Among those who came to

Montreal to trade with the

Nor'-Westers and to receive their hospitality

was a German merchant of New York, named John

Jacob Astor. This man, who is the ancestor of

the distinguished family of Astors at the

present time in New York, came over from

London to the New World and immediately began

to trade in furs. For several years Astor

traded in Montreal, and shipped the furs

purchased to London, as there was a law

against exporting from British possessions.

After Jay's treaty of amity and commerce

(1794) this restriction was removed, and Astor

took Canadian furs to the United States, and

even exported them to China, where high prices

ruled.

While Astor's ambition

led him to aim at controlling the fur trade in

the United States, the fact that the western

posts, such as Detroit and Michilimackinac,

had not been surrendered to the United States

till after Jay's treaty, had allowed the

British traders of these and other posts of

the West to strengthen themselves. Such daring

traders as Murdoch Cameron, Dickson, Fraser,

and Rolette could not be easily beaten on the

ground where they were so familiar, and where

they had gained such an ascendancy over the

Indians. The Mackinaw traders were too strong

for Astor, and the hope of overcoming them

through the agency of the "American Fur

Company," which he had founded in 1809, had to

be given up by him. What could not be

accomplished by force could, however, be

gained by negotiation, and so two years

afterward, with the help of certain partners

from among the Nor'-Westers in Montreal, Astor

brought out the Mackinaw traders (1811), and

established what was called the "South-West

Company."

During these same years,

the St. Louis merchants organized a company to

trade upon the Missouri and Nebraska Rivers.

This was known as the Missouri Company, and

with its 250 men it pushed its trade, until in

1808, one of its chief traders crossed the

Rocky Mountains, and built a fort on the

western slope. This was, however, two years

afterward given up on account of the hostility

of the natives. A short time after this, the

Company passed out of existence, leaving the

field to the enterprising merchant of New

York, who, in 1810, organized his well-known

"Pacific Fur Company."

During these eventful

years, the resourceful Astor was, with the

full knowledge of the American Government,

steadily advancing toward gaining a monopoly

of the fur trade of the United States.

Jonathan Carver, a British officer, had, more

than thirty years before this, in company with

a British Member of Parliament named

Whitworth, planned a route across the

continent. Had not the American Revolution

commenced they would have built a fort at Lake

Pepin in Minnesota, gone up a tributary of the

Mississippi to the West, till they could

cross, as they thought would be possible, to

the Missouri, and ascending it have reached

the Rocky Mountain summit. At this point they

expected to come upon a river, which they

called the Oregon, that would take them to the

Pacific Ocean.

The plan projected by

Carver was actually carried out by the

well-known explorers Lewis and Clark in

1804-6. Astor's penetrating mind now saw the

situation clearly. He would erect a line of

trading posts up the Missouri River and across

the Rockies to the Columbia River on the

Pacific Coast and while those on the east of

the Rockies would be supplied from St. Louis,

he would send ships to the mouth of the

Columbia, and provide for the posts on the

Pacific slope from the West. With great skill

Astor made approaches to the Russian Fur

Company on the Pacific Coast, offering his

ships to supply their forts with all needed

articles, and he thus established a good

feeling between himself and the Russians.

The only other element of

danger to the mind of Astor was the opposition

of the North-West Company on the Pacific

Coast. He knew that for years the Montreal

merchants had had their eye on the region that

their partner Sir Alexander Mackenzie, had

discovered. Moreover, their agents, Thompson,

Fraser, Stuart, and Finlay the younger, were

trading beyond the summit of the Rockies in

New Caledonia, but the fact that they were

farther north held out some hope to Astor that

an arrangement might be made with them. He

accordingly broached the subject to the

North-West Company and proposed a combination

with them similar to that in force in the

co-operation in the South-West Company, viz.

that they should take a one-third interest in

the Pacific Fur Company. After certain

correspondence, the North-West Company

declined the offer, no doubt hoping to

forestall Astor in his occupation of the

Columbia. They then gave orders to David

Thompson to descend the Columbia, whose upper

waters he had already occupied, and he would

have done this had not a mutiny taken place

among his men, which made his arrival at the

mouth of the Columbia a few months too late.

Astor's thorough

acquaintance with the North-West Company and

its numerous employes stood him in good stead

in his project of forming a company. After

full negotiations he secured the adhesion to

his scheme of a number of well-known

Nor'-Westers. Prominent among these was

Alexander McKay, who was Sir Alexander

Mackenzie's most trusted associate in the

great journey of 1793 to the Pacific Ocean.

McKay had become a partner of the North-West

Company, and left it to join the Pacific Fur

Company. Most celebrated as being in charge of

the Astor enterprise on the coast was Duncan

McDougall, who also left the North-West

Company to embark in Astor's undertaking. Two

others, David Stuart and his nephew Robert

Stuart, made the four partners of the new

Company who were to embark from New York with

the purpose of doubling the Cape and reaching

the mouth of the Columbia.

A company of clerks and

engages had been obtained in Montreal, and the

party leaving Canada went in their great canoe

up Lake Champlain, took it over the portage to

the Hudson, and descended that river to New

York. They transferred the picturesque scene

so often witnessed on the Ottawa to the sleepy

banks of the Hudson River, and with emblems

flying, and singing songs of the voyageurs,

surprised the spectators along the banks.

Arrived at New York the men with bravado

expressed themselves as ready to endure

hardships. As Irving puts it, they declared

"they could live hard, lie hard, sleep hard,

eat dogs—in short, endure anything."

But these partners and

men had much love for their own country and

little regard to the new service into which

desire for gain had led them to embark. It was

found out afterwards that two of the partners

had called upon the British Ambassador in New

York, had revealed to him the whole scheme of

Mr. Astor, and enquired whether, as British

subjects, they might embark in the enterprise.

The reply of the diplomat assured them of

their full liberty in the matter. Astor also

required of the employes that they should

become naturalized citizens of the United

States. They professed to have gone through

the ceremony required, but it is contended

that they never really did so.

The ship in which the

party was to sail was the Tonquin, commanded

by a Captain Thorn, a somewhat stern officer,

with whom the fur traders had many conflicts

on their outbound Journey. The report having

gone abroad that a British cruiser from

Halifax would come down upon the Tonquin and

arrest the Canadians on board her, led to the

application being made to the United States

frigate Constitution to give the vessel

protection. On September 10th, 1810, the

Tonquin with her convoy put out and sailed for

the Southern Slain.

Notwithstanding the

constant irritation between the captain and

his fur trading passengers, the vessel went

bravely on her way. After doubling Capo Horn

on Christmas Day, they reached the Sandwich

Islands in February, and after paying visits

of ceremony to the king, obtained the

necessary supplies of hogs, fruits,

vegetables, and water from the inhabitants,

and also engaged some twenty-four of the

islanders, or Kanakas, as they are called, to

go as employes to the Columbia.

Like a number of

rollicking lads, the Nor'-Westers made very

free with the natives, to the disgust of

Captain Thorn. He writes:—"They sometimes

dress in red coats and otherwise very

fantastically, and collecting a number of

ignorant natives around them, tell them they

are the great chiefs of the North-West. . . .

then dressing in Highland plaids and kilts,

and making bargains with the natives, with

presents of rum, wine, or anything that is at

hand."

On February 28th the

Tonquin set sail from the Sandwich Islands.

The discontent broke out again, and the fur

traders engaged in a mock mutiny, which

greatly alarmed the suspicious captain. They

spoke to each other in Gaelic, had long

conversations, and the captain kept an

ever-watchful eye upon them; but on March 22nd

they arrived at the mouth of the Columbia

River.

McKay and McDougall, as

senior partners, disembarked, visited the

village of the Chinooks, and were warmly

welcomed by Comcomly, the chief of that tribe.

The chief treated them hospitably and

encouraged their settling in his neighbourhood.

Soon they had chosen a site for their fort,

and with busy hands they cut down trees,

cleared away thickets, and erected a

residence, stone-house, and powder magazine,

which was not, however, at first surrounded

with palisades. In honour of the promoter of

their enterprise, they very naturally called

the new settlement Astoria.

As soon as the new fort

had assumed something like order, the Tonquin,

according to the original design, was

despatched up the coast to trade with the

Indians for furs. Alexander McKay took charge

of the trade, and sought to make the most of

the honest but crusty captain. The vessel

sailed on July 5th, 1811, on what proved to be

a disastrous Journey.

As soon as she was gone

reports began to reach the traders at Astoria

that a body of white men were building a fort

far up the Columbia. This was serious news,

for if true it meant that the supply of furs

looked for at Astoria would be cut off. An

effort was made to find out the truth of the

rumour, without success, but immediately after

came definite information that the North-West

Company agents were erecting a post at

Spokane. We have already seen that this was

none other than David Thompson, the emissary

of the North-West Company, sent to forestall

the building of Astor's fort.

Though too late to fulfil

his mission, on July 15th the doughty

astronomer and surveyor, in his canoe manned

by eight men and having the British ensign

flying, stopped in front of the new fort.

Thompson was cordially received by McDougall,

to the no small disgust of the other employes

of the Astor Company. After waiting for eight

days, Thompson, having received supplies and

goods from McDougall, started on his return

journey. With him journeyed up the river David

Stuart, who, with eight men, was proceeding on

a fur-trading expedition. Among his clerks was

Alexander Ross, who has left a veracious

history of the "First Settlers on the Oregon."

Stuart had little confidence in Thompson, and

by a device succeeded in getting him to

proceed on his journey and leave him to choose

his own site for a fort. Going up to within

140 miles of the Spokane River, and at the

junction of the Okanagan and Columbia, Stuart

erected a temporary fort to carry on his first

season's trade.

In the meantime the

Tonquin had gone on her way up the coast. The

Indians were numerous, but were difficult to

deal with, being impudent and greedy. A number

of them had come upon the deck of the Tonquin,

and Captain Thorn, being wearied with their

slowness in bargaining and fulness of wiles,

had grown impatient with the chief and had

violently thrown him over the side of the

ship. The Indians no doubt intended to avenge

this insult. Next morning early, a multitude

of canoes came about the Tonquin and many

savages clambered upon the deck. Suddenly an

attack was made upon the fur traders.

Alexander McKay was one of the first to fall,

being knocked down by a war club. Captain

Thorn fought desperately, killing the young

chief of the band, and many others, until at

last he was overcome by numbers. The remnant

of the crew succeeded in getting control of

the ship and, by discharging some of the deck

guns, drove off the savages. Next morning the

ship was all quiet as the Indians came about

her. The ship's clerk, Mr. Lewis, who had been

severely wounded, appeared on deck and invited

them on board. Soon the whole deck was crowded

by the Indians, who thought they would secure

a prize. Suddenly a dreadful explosion took

place. The gunpowder magazine had blown up,

and Lewis and up-ward of one hundred savages

were hurled into eternity. It was a fierce

revenge! Four white men of the crew who had

escaped in a boat were captured and terribly

tortured by the maddened Indian survivors. An

Indian interpreter alone was spared to return

to Astoria to relate the tale of treachery and

blood.

Astor's plan involved,

however, the sending of another expedition

overland to explore the country and lay out

his projected chain of forts. In charge of

this party was William P. Hunt, of Trenton,

New Jersey, who had been selected by Astor, as

being a native-born American, to be next to

himself in authority in the Company. Hunt had

no experience as a fur trader, but was a man

of decision and perseverance. With him was

closely associated Donald McKenzie, who had

been in the service of the North-West Company,

but had been induced to join in the

partnership with Astor.

Hunt and McKenzie arrived

in Montreal on June 10th, 1811, and engaged a

number of voyageurs to accompany them. With

these in a great canoe the party left the

church of La Bonne Ste. Anne, on Montreal

Island, and ascended the Ottawa. By the usual

route Michilimackinac was reached, and here

again other members of the party were

enlisted. The party was also reinforced by the

addition of a young Scotchman of energy and

ability, Ramsay Crooks, and with him an

experienced and daring Missouri trader named

Robert McLellan. At Mackinaw as well as at

Montreal the influence of the North-West

Company was so strong that men engaged for the

Journey were as a rule those of the poorest

quality. Thus were the difficulties of the

overland party increased by the Falstaffian

rabble that attended the well-chosen leaders.

The party left Mackinaw,

crossed to the Mississippi, and reached St.

Louis in September.

At St. Louis the

explorers came into touch with the Missouri

Company, of which we have spoken. The same

hidden opposition that had met them in

Montreal and Mackinaw was here encountered.

Nothing was said, but it was difficult to get

information, hard to induce voyageurs to join

them, and delay after delay occurred. Near the

end of October St. Louis was left behind and

the Missouri ascended for 450 miles to a fort

Nodowa, when the party determined to winter.

During the winter Hunt returned to St. Louis

and endeavoured to enlist additional men for

his expedition. In this he still had the

opposition of a Spaniard, Manuel de Lisa, who

was the leading spirit in the Missouri

Company. After some difficulty Hunt engaged an

interpreter, Pierre Dorion, a drunken French

half-breed, who was, however, expert and even

accomplished in his work.

A start was at last made

in January, and Irving tells us of the

expedition meeting Daniel Boone, the famous

old hunter of Kentucky, one who gloried in

keeping abreast of the farthest line of the

frontier, a trapper and hunter. The party went

on its way ascending the river, and was

accompanied by the somewhat disagreeable

companion Lisa. At length they reached the

country of the Anckaras, who, like the

Parthians of old, seemed to live on horseback.

After a council meeting the distrust of Lisa

disappeared, and a bargain was struck between

the Spaniard and the explorer by which he

would supply them with 130 horses and take

their boats in exchange. Leaving in August the

party went westward, keeping south at first to

avoid the Blackfeet, and then, turning

northward till they reached an old trading

post Just beyond the summit.

The descent was now to be

made to the coast, but none of them had the

slightest conception of the difficulties

before them. They divided themselves into four

parties, under the four leaders, McKenzie,

McLellan, Hunt, and Crooks. The two former

took the right bank, the two latter the left

bank of the river. For three weeks they

followed the rugged banks of this stream,

which, from its fierceness, they spoke of as

the "Mad River." Their provisions soon became

exhausted and they were reduced to the dire

necessity of eating the leather of their

shoes. After a separation of some days the

plan was struck upon by Mr. Hunt of gaining

communication across the river by a boat

covered with horse skin. This failed, and the

unfortunate voyageur attempting to cross in it

was drowned. After a time the Lewis River was

reached. Trading off their horses, McKenzie's

party, which was on the right bank, obtained

canoes from the natives, and at length on

January 18th, 1812, this party reached

Astoria. Ross Cox says: "Their concave cheeks,

protuberant bones, and tattered garments

strongly indicated the dreadful extent of

their privations; but their health appeared

uninjured and their gastronomic powers

unimpaired."

After the disaster of the

horse-skin boat the two parties lost sight of

one another. Mr. Hunt had the easier bank of

the river, and, falling in with friendly

Indians, he delayed for ten days and rested

his wearied party. Though afterward delayed,

Hunt, with his following of thirty men, one

woman, and two children, arrived at Astoria,

to the great delight of his companions, on

February 15th, 1812.

Various accounts have

been given of the journey. Those of Ross Cox

and Alexander Ross are the work of actual

members of the Astor Company, though not of

the party which really crossed. Washington

Irving's "Astoria" is regarded as a pleasing

fiction, and he is very truly spoken of by Dr.

Coues, the editor of Henry and Thompson's

journals, in the following fashion:—"No story

of travel is more familiar to the public than

the tale told by Irving of this adventure,

because none is more readable as a romance

founded upon fact. . . . Irving plies his

golden pen elastically, and from it flow wit

and humour, stirring scene, and startling

incident, character to the life. But he never

tells us where those people went, perhaps for

the simple reason that he never knew. He wafts

us westward on his strong plume, and we look

down on those hapless Astorians; but we might

as well be ballooning for aught of exactitude

we can make of this celebrated itinerary."

In October, 1811, the

second party by sea left New York on the ship

Beaver, to join the traders at the mouth of

the Columbia. Ross Cox, who was one of the

clerks, gives a most interesting account of

the voyage and of the affairs of the Company.

With him were six other cabin passengers. The

ship was commanded by Captain Sowles. The

voyage was on the whole a prosperous one, and

Cape Horn was doubled on New Year's Day, 1812.

More than a month after, the ship called at

Juan Fernandez, and two months after crossed

the Equator. Three weeks afterward she reached

the Sandwich Islands, and on April 9th, after

a further voyage, arrived at the mouth of the

Columbia.

On arriving at Astoria

the new-comers had many things to see and

learn, but they were soon under way, preparing

for their future work. There were many risks

in thus venturing away from their fort. Chief

Trader McDougall had indeed found the fort

itself threatened after the disaster of the

Tonquin. He had, however, boldly grappled with

the case. Having few of his company to support

him, he summoned the Indans to meet him. In

their presence he informed them that he

understood they were plotting against him,

but, drawing a corked bottle from his pocket,

he said : "This bottle contains small-pox. I

have but to draw out the cork and at once you

will be seized by the plague." They implored

him to spare them and showed no more

hostility.

Such recitals as this,

and the sad story of the Tonquin related to

Ross Cox and his companions, naturally

increased their nervousness as to penetrating

the interior.

The Beaver had sailed for

Canton with furs, and the party of the

interior was organized with three proprietors,

Ramsay Crooks, Robert McLellan, and Robert

Stuart, who, with eight men, were to cross the

mountains to St. Louis. At the fort there

remained Mr. Hunt, Duncan McDougall, B. Clapp,

J. C. Halsey, and Gabriel Franchere, the last

of whom wrote an excellent account in French

of the Astor Company affairs.