Nor'-Westers oppose

the colony—Reason why—A considerable

literature—Contentions of both

parties—Both in fault—Miles Macdonell's

mistake—Nor' -Wester arrogance—Duncan

Cameron's ingenious plan—Stirring up the

Chippewas—Nor'-Westers warn colonists to

depart—McLeod's hitherto unpublished

narrative—Vivid account of a brave defence—Chain

shot from the blacksmith's smithy—Fort

Douglas begun—Settlers driven out

—Governor Semple arrives—Cameron last

Governor of Fort Gibraltar—Cameron sent to

Britain as a prisoner—Fort Gibraltar

captured—Fort Gibraltar decreases, Fort

Douglas increases— Free traders take to

the plains—Indians favour the colonists.

To the most casual

observer it must have been evident that

the colony to be established by Lord

Selkirk would be regarded with disfavour

by the North-West Company officers. The

strenuous opposition shown to it in Great

Britain by Sir Alexander Mackenzie, and by

all who were connected with him, showed

quite clearly that it would receive little

favour on the Red River.

First, it was a

Hudson's Bay scheme, and would greatly

advance the interests of the English

trading Company. That Company would have

at the very threshold of the fur country a

depot, surrounded by traders and workmen,

which would give them a great advantage

over their rivals.

Secondly, civilization and its handmaid

agriculture are incompatible with the fur

trade. As the settler enters, the

fur-bearing animals are exterminated. A

sparsely settled, almost unoccupied

country, is the only hope of preserving

this trade.

Thirdly, the claim of

the Hudson's Bay Company under its charter

was that they had the sole right to pursue

the fur trade in Rupert's Land. Their

traditional policy on Hudson Bay had been

to drive out private trade, and to

preserve their monopoly.

Fourthly, the

Nor'-Westers claimed to be the lineal

successors of the French traders, who,

under Verendrye, had opened up the region

west of Lake Superior. They long after

maintained that priority of discovery and

earlier possession gave them the right to

claim the region in dispute as belonging

to the province of Quebec, and so as being

a part of Canada.

The first and second

parties of settlers were so small, and

seemed so little able to cope with the

difficulties of their situation, that no

great amount of opposition was shown. They

were made, it is true, the laughing-stock

of the half-breeds and Indians, for these

free children of the prairies regarded the

use of the hoe or other agricultural

implement as beneath them. The term

"Pork-eaters," applied, as we have seen,

to the voyageurs east of Fort William, was

freely applied to these settlers, while

the Indians used to call them the French

name "jardinieres" or clod-hoppers.

A considerable

literature is in existence dealing with

the events of this period. It is somewhat

difficult, in the conflict of opinion, to

reach a basis of certainty as to the facts

of this contest. The Indian country is

proverbial for the prevalence of rumour

and misrepresentation. Moreover, prejudice

and self-interest were mingled with deep

passion, so that the facts are very hard

to obtain.

The upholders of the

colony claim that no sooner had the

settlers arrived than efforts were made to

stir up the Indians against them ; that

besides, the agents of the North-West

Company had induced the Metis, or

half-breeds, to disguise themselves as

Indians, and that on their way to Pembina

one man was robbed by these desperadoes of

the gun which his father had carried at

Culloden, a woman of her marriage ring,

and others of various ornaments and

valuable articles. There were, however, it

is admitted, no specially hostile acts

noticeable during the years 1812 and 1813.

The advocates of the

North-West Company, on the other hand,

blame the first aggression on Miles

Macdonell. During the winter of 1813 and

1814 Governor Macdonell and his colonists

wore occupying Fort Daer and Pembina. The

supply of subsistence from the buffalo was

short, food was difficult to obtain, the

war with the United States was in progress

and might cut off communication with

Montreal, and moreover, a body of

colonists was expected to arrive during

the year from Great Britain. Accordingly,

the Governor, on January 8th, 1814, issued

a proclamation.

He claimed the

territory as ceded to Lord Selkirk, and

gave the description of the tract thus

transferred. The proclamation then goes on

to say: "And whereas the welfare of the

families at present forming the

settlements on the Red River within the

said territory, with those on their way to

it, passing the winter at York or

Churchill Forts on Hudson Bay, as also

those who are expected to arrive next

autumn, renders it a necessary and

indispensable part of my duty to provide

for their support. The uncultivated state

of the country, the ordinary resources

derived from the buffalo, and other wild

animals hunted within the territory, are

not deemed more than adequate for the

requisite supply; wherefore, it is hereby

ordered that no persons trading in furs or

provisions within the territory, for the

Honourable the Hudson's Bay Company, the

North-West Company, or any individual or

unconnected traders whatever, shall take

out any provisions, either of flesh,

grain, or vegetables, procured or raised

within the territory, by water or

land-carriage for one twelvemonth from the

date hereof ; save and except what may be

judged necessary for the trading parties

at the present time within the territory,

to carry them to their respective

destinations, and who may, on due

application to me, obtain licence for the

same. The provisions procured and raised

as above, shall be taken for the use of

the colony, and that no losses may accrue

to the parties concerned, they will be

paid for by British bills at the customary

rates, &c."

The Nor'-Westers then

recalled the ceremonies with which

Governor Macdonell had signalized his

entrance to the country: "When he arrived

he gathered his company about him, made

before it some impressive ceremonies,

drawn from the conjuring book of his

lordship, and read to it his commission of

governor or representative of Lord

Selkirk; afterwards a salute was fired

from the Hudson's Bay Company fort, which

proclaimed his taking possession of the

neighbourhood."

The Governor,

however, soon gave another example of his

determination to assert his authority. It

had been represented to him that the

North-West Company officers had no

intention of obeying the proclamation, and

indeed were engaged in buying up all the

available supplies to prevent his getting

enough for his colonists- Convinced that

his opponents were engaged in thwarting

his designs, the Governor sent John

Spencer to seize some of the stores which

had been gathered in the North-West post

at the mouth of the Souris River. Spencer

was unwilling to go, unless very specific

instructions were given him. The Governor

had, by Lord Selkirk's influence in

Canada, been appointed a magistrate, and

he now issued a warrant authorizing

Spencer to seize the provisions in this

fort.

Spencer, provided

with a double escort, proceeded to the

fort at the Souris, and the Nor'-Westers

made no other resistance than to retire

within the stockade and shut the gate of

the fort. Spencer ordered his men to force

an entrance with their hatchets.

Afterwards, opening the store-houses, they

seized six hundred skins of dried meat

(pemmican) and of grease, each weighing

eighty-five pounds. This booty was removed

into the Hudson's Bay Company fort

(Brandon House) at that place.

We have now before us

the first decided action that led to the

serious disturbances that followed. The

question arises, Was the Governor

justified in the steps taken by him? No

doubt, with the legal opinion which Lord

Selkirk had obtained, he considered

himself thoroughly justified. The

necessities of his starving people and the

plea of humanity were certainly strong

motives urging him to action. No doubt

these considerations seemed strong, but,

on the other hand, he should have

remembered that the idea of law in the fur

traders' country was a new thing, that the

Nor'-Westers, moreover, were not prepared

to credit him with purity of motive, and

that they had at their disposal a force of

wild Bois Brules ready to follow the

unbridled customs of the plains. Further,

even in civilized communities laws of

non-intercourse, embargo, and the like,

are looked upon as arbitrary and of

doubtful validity. All these things should

have led the Governor, ill provided as he

was with the force necessary for his

defence, to hesitate before taking a

course likely to be disagreeable to the

Nor"-Westers, who would regard it as an

assertion of the claim of superiority of

the Hudson's Bay Company and of the

consequent degradation of their Company,

of which they were so proud.

In their writings the

North-West Company take some credit for

not precipitating a conflict, but state

that they endured the indignity until

their council at Fort William should take

action in the following summer. At this

council, which was interesting and full of

strong feeling against their fur-trading

rivals, the Nor'-Westers, under the

presidency of the Hon. William

McGillivray, took decided action.

In the trials that

afterwards arose out of this unfortunate

quarrel, John Pritchard, whose forty days'

wanderings we have recorded, testified

that one of the North-West agents, Mac-Kenzie,

had given him the information that "the

intention of the North-West Company was to

seduce and inveigle away as many of the

colonists and settlers at Red River as

they could induce to join them ; and after

they should thus have diminished their

means of defence, to raise the Indians of

Lac Rouge, Fond du Lac, and other places,

to act and destroy the settlement; and

that it was also their intention to bring

the Governor, Miles Macdonell, down to

Montreal as a prisoner, by way of

degrading the authority under which the

colony was established in the eyes of the

natives of that country."

Simon McGillivray, a

North-West Company partner, had two years

before this written from London that "Lord

Selkirk must be driven to abandon his

project, for his success would strike at

the very existence of our trade."

Two of the most

daring partners of the North-West Company

were put in charge of the plan of campaign

agreed on at Fort William. These were

Duncan Cameron and Alexander Macdonell.

The latter wrote to a friend, from one of

his resting-places on his journey, "Much

is expected of us. . . . so here is at

them with all my heart and energy." The

two partners arrived at Fort Gibraltar,

situated at the forks of the Red and

Assiniboine Rivers, toward the end of

August. The senior partner, Macdonell,

leaving Cameron at Fort Gibraltar, went

westward to the Qu'Appelle River, to

return in the spring and carry out the

plan agreed on.

Cameron had been busy

during the winter in dealing with the

settlers, and let no opportunity slip of

impressing them. Knowing the fondness of

Highlanders for military display, he

dressed himself in a bright red coat, wore

a sword, and in writing to the settlers,

which he often did, signed himself, "D.

Cameron, Captain, Voyageur Corps,

Commanding Officer, Red River." He also

posted an order at the gate of his fort

purporting to be his captain's commission.

Some dispute has arisen as to the validity

of this authority. There seems to have

been some colour for the use of this

title, under authority given for enlisting

an irregular- corps in the upper lakes

during the American War of 1812, but the

legal opinion is that this had no validity

in the Red River settlement.

Cameron, aiming at

the destruction of the colony, began by

ingratiating himself with a number of the

leading settlers. Knowing the love of the

Highlanders for their own language,

Cameron spoke to them Gaelic in his most

pleasing manner, entertained the leading

colonists at his own table, and paid many

attentions to their families. Promises

were then made to a number of leaders to

provide the people with homes in Upper

Canada, to pay up wages due by the

Hudson's Bay Company or Lord Selkirk, and

to give a year's provisions free, provided

the colony would leave the Rod River and

accept the advantages offered in Canada.

This plan succeeded remarkably well, and

it is in sworn evidence that on

three-quarters of the colony reaching Fort

William, a settler, Campbell, received

100l., several others 20l., and so on.

Some of the best of

the settlers, amounting to about

one-quarter of the whole, refused all the

advances of the subtle captain. Another

method was taken with this class. The plan

of frightening them away by the

co-operation of the Cree Indians had

failed, but the Bois Brules, or

half-breeds, were a more pliant agency.

These were to be employed. Cameron now

(April, 1815) made a demand on Archibald

Macdonald, Acting Governor, to hand over

to the settlers the field pieces belonging

to Lord Selkirk, on the ground that these

had been used already to disturb the

peace. This startling order was presented

to the Governor by settler Campbell on the

day on which the fortnightly issue of

rations took place at the colony

buildings. The settlers in favour of

Cameron then broke open the store-house,

and took nine pieces of ordnance and

removed them to Fort Gibraltar. The

Governor having arrested one of the

settlers who had broken open the

store-house, a number of the North-West

Company clerks and servants, under orders

from Cameron, broke into the Governor's

house and rescued the prisoner.

About this time Miles

Macdonell, the Governor, returned to the

settlement. A warrant had been issued for

his arrest by the Nor'-Westers, but he

refused for the time to acknowledge the

jurisdiction of the magistrates. Cameron

now spread abroad the statement that if

the settlers did not deliver up the

Governor, they in turn would be attacked

and driven from their homes. Certain

colonists were now fired at by unseen

assailants.

About the middle of May, the senior

partner, Alexander Macdonell, arrived from

Qu'Appelle, accompanied by a band of Cree

Indians. The partners hoped through these

to frighten the settlers who remained

obdurate, but the Indians were too astute

to be led into the quarrel, and assured

Governor Miles Macdonell that they were

resolved not to molest the newcomers.

An effort was also made to stir up the

Chippewa Indians of Sand Lake, near the

west of Lake Superior. The chief of the

band declared to the Indian Department of

Canada that he was offered a large reward

if he would declare war against the

Selkirk colonists. This the Chippewas

refused to do.

Early in June the lawless spirit followed

by the Nor'-Westers again showed itself. A

party from Fort Gibraltar went down with

loaded muskets, and from a wood near the

Governor's residence fired upon some of

the colony employes. Mr. White, the

surgeon, was nearly hit, and a ball passed

close by Mr. Burke, the storekeeper.

General firing then began from the wood

and was returned from the house, but four

of the colony servants were wounded. This

expedition was under Cameron, who

congratulated his followers on the result.

The demand for the surrender of the

Governor, in answer to the warrant issued,

was then made, and at the persuasion of

the other officers of the settlement, and

to avoid the loss of life and the dangers

threatened against the colonists, Governor

Miles Macdonell surrendered himself and

was taken to Montreal for trial, though no

trial ever took place.

The double plan of coaxing away all the

settlers who were open to such inducement,

and of then forcibly driving away the

residue from the settlement, seemed likely

to succeed. One hundred and thirty-four of

the colonists, induced by promises of free

transport, two hundred acres of land in

Upper Canada, as well as in some cases by

substantial gifts, deserted the colony in

June (1815), along with Cameron, and

arrived at Fort William on their way down

the lakes at the end of July. These

settlers made their way in canoes along

the desolate shores of Lake Superior and

Georgian Bay, and arrived at Holland

Landing, in Upper Canada, on September

5th. Many of them were given land in the

township of West Guillimbury, near

Newmarket, and many of their descendants

are there to this day.

The Nor'-Westers now continued their

persecution of the remnant of the

settlers. They burnt some of their houses

and used threats of the most extreme kind.

On June 25th, 1815, the following document

was served upon the disheartened colonists

:—

"All settlers to retire immediately from

the Red River, and no trace of a

settlement to remain.

"Cuthbert Grant.

"Bostonnais pangman.

"William Shaw.

"Bonhomme Montour."

The conflict resulting at this time may be

said to be the first battle of the war. A

fiery Highland trader, John McLeod, was in

charge of the Hudson's Bay Company house

at this point, and we have his account of

the attack and defence, somewhat bombastic

it may be, but which, so far as known to

the author, has never been published

before.

COPY OF DIARY IN PROVINCIAL LIBRARY,

WINNIPEG.

"In 1814-15, being in charge of the whole

Red River district, I spent the winter at

the Forks, at the settlement there. On

June 25th, 1815, while I was in charge, a

sudden attack was made by an armed band of

the N.-W. party under the leadership of

Alexander Maedonell (Yellow Head) and

Cuthbert Grant, on the settlement and

Hudson's Bay Company fort at the Forks.

They numbered about seventy or eighty,

well armed and on horsebark. Having had

some warning of it, I assumed command of

both the colony and H. B. C. parties.

Mustering with inferior numbers, and with

only a few guns, we took a stand against

them. Taking my place amongst the

colonists, I fought with them. All fought

bravely and kept up the fight as long as

possible. Many all about me falling

wounded ; one mortally. Only thirteen out

of our band escaped unscathed.

"The brunt of the struggle was near the H.

B. C. post, close to which was our

blacksmith's smithy—a log building about

ten feet by ten. Being hard pressed, I

thought of trying the little cannon (a

three or four-pounder) lying idle in the

post where it could not well be used.

"One of the settlers (Hugh McLean) went

with two of my men, with his cart to fetch

it, with all the cart chains he could get

and some powder. Finally, we got the whole

to the blacksmithy, where, chopping up the

chain into lengths for shot, we opened a

fire of chain shot on the enemy which

drove back the main body and scattered

them, and saved the post from utter

destruction and pillage. All the colonists

'houses were, however, destroyed by fire.

Houseless, wounded, and in extreme

distress, they took to the boats, and,

saving what they could, started for Norway

House (Jack's River), declaring they would

never return.

"The enemy still prowled about, determined

apparently to expel, dead or alive, all of

our party. All of the H. B. Company's

officers and men refused to remain, except

the two brave fellows in the service, viz.

Archibald Currie and James Mcintosh, who,

with noble Hugh McLean, joined in holding

the fort in the smithy. Governor Macdonell

was a prisoner.

"In their first approach the enemy

appeared determined more to frighten than

to kill. Their demonstration in line of

battle, mounted, and in full 'war paint'

and equipment was formidable, but their

fire, especially at first, was desultory.

Our party, numbering only about half

theirs, while preserving a general line of

defence, exposed itself as little as

possible, but returned the enemy's fire,

sharply checking the attack, and our line

was never broken by them. On the contrary,

when the chain-firing began, the enemy

retired out of range of our artillery, but

at a flank movement reached the colony

houses, where they quickly and

resistlessly plied the work of

destruction. To their credit be it said,

they took no life or property.

"Of killed, on our side, there was only

poor John Warren of H. B. C. service, a

worthy brave gentleman, who, taking a

leading part in the battle, too fearlessly

exposed himself. Of the enemy, probably,

the casualties were greater, for they

presented a better target, and we

certainly fired to kill. From the smithy

we could and did protect the trade post,

but could not the buildings of the

colonists, which were along the bank of

the Red River, while the post faced the

Assiniboine more than the Red River.

Fortunately for us in the 'fort' (the

smithy) the short nights were never too

dark for our watch and ward.

"The colonists were allowed to take what

they could of what belonged to them, and

that was but little, for as yet they had

neither cow nor plough, only a horse or

two. There were boats and other craft

enough to take them all—colonists and H.

B. C. people—away, and all, save my three

companions already named and myself, took

ship and fled. For many days after we were

under siege, living under constant peril;

but unconquerable in our bullet-proof log

walls, and with our terrible cannon and

chain shot.

"At length the enemy retired. The post was

safe, with from 800l., to 1000l. sterling

worth of attractive trade goods belonging

to the Hudson's Bay Company untouched. I

was glad of this, for it enabled me to

secure the services of free men about the

place—French Canadians and half-breeds not

in the service of the N.-W. Company—to

restore matters and prepare for the

future.

"I felt that we had too much at stake in

the country to give it up, and had every

confidence in the resources of the H. B.

Company and the Earl of Selkirk to hold

their own and effectually repel any future

attack from our opponents.

"I found the free men about the place

willing to work for me; and at once hired

a force of them for building and other

works in reparation of damages and in new

works. So soon as I got my post in good

order, I turned to save the little but

precious and promising crops of the

colonists, whose return I anticipated,

made fences where required, and in due

time cut and stacked their hay, &c.

"That done I took upon me, without order

or suggestion from any quarter, to build a

house for the Governor and his staff of

the Hudson's Bay Company at Red River.

There was no such officer at that time,

nor had there ever been, but I was aware

that such an appointment was contemplated.

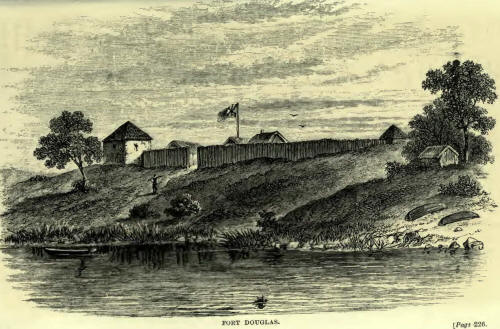

"I selected for this purpose what I

considered a suitable site at a point or

sharp bend in the Red River about two

miles below the Assiniboine, on a slight

rise on the south side of the point—since

known as Point Douglas, the family name of

the Earl of Selkirk. Possibly I so

christened it—I forget.

"It was of two stories; with main timbers

of oak; a good substantial house; with

windows of parchment in default of glass."

Here ends McLeod's diary.

The Indians of the vicinity showed the

colonists much sympathy, but on June 27th,

after the hostile encounter, some thirteen

families, comprising from forty to sixty

persons, pursued their sad Journey,

piloted by friendly Indians, to the north

end of Lake Winnipeg, where the Hudson's

Bay Company post of Jack River afforded

some shelter. McLeod and, as he tells us,

three men only were left. These

endeavoured to protect the settlers'

growing crops, which this year showed

great promise.

The expulsion may now be said to have been

complete. The day after the departure of

the expelled settlers, the colony

dwellings, with the possible exception of

the Governor's house, were all burnt to

the ground. In July the desolate band

reached Jack River House, their future

being dark indeed. Deliverance was,

however, coming from two directions. Colin

Robertson, a Hudson's Bay Company officer,

arrived from the East with twenty

Canadians. On reaching the Red River

settlement, he found the settlers all

gone, but he followed them speedily to

their rendezvous on Lake Winnipeg and

returned with the refugees to their

deserted homes on Red River. They were

joined also by about ninety settlers from

the Highlands of Scotland, who had come

through to Red River in one season. The

colony was now rising into promise again.

A number of the demolished buildings were

soon erected ; the colony took heart, and

under the new Governor, Robert Semple, a

British officer who had come with the last

party of settlers, the prospects seemed to

have improved. The Governor's dwelling was

strengthened, other dwellings were erected

beside it, and more necessity being now

seen for defence, the whole assumed a more

military aspect, and took the name, after

Lord Selkirk's family name, Fort Douglas.

Though a fair crop had been reaped by the

returned settlers from their fields, yet

the large addition to their numbers made

it necessary to remove to Fort Daer, where

the buffalo were plentiful. This party was

under the leadership of Sheriff Alexander

Macdonell, though Governor Semple was also

there. The autumn saw trouble at the

Forks. The report of disturbances having

taken place between the Nor'-Westers and

Hudson's Bay Company employes at

Qu'Appelle was heard, as well as renewed

threats of disturbance in the colony.

Colin Robertson in October, 1815, captured

Fort Gibraltar, seized Duncan Cameron, and

recovered the field-pieces and other

property taken by the Nor'-Westers in the

preceding months. Though the capture of

Cameron and his fort thus took place, and

the event was speedily followed by the

reinstatement of the trader on his promise

to keep the peace, yet the report of the

seizure led to the greatest irritation in

all parts of the country where the two

Companies had posts. All through the

winter, threatenings of violence filled

the air. The Bois Brutes were arrogant,

and, led by their faithful leader,

Cuthbert Grant, looked upon themselves as

the "New Nation."

Returning, after the New Year of 1816,

from Fort Daer, Governor Semple saw the

necessity for aggressive action. Fort

Gibraltar was to become the rendezvous for

a Bois Brules force of extermination from

Qu'Appelle, Fort des Prairies (Portage la

Prairie), and even from the Saskatchewan-

To prevent this, Colin Robertson, under

the Governor's direction, recaptured Fort

Gibraltar and held Cameron as a prisoner.

This event took place in March or April of

1816. The legality of this seizure was of

course much discussed between the hostile

parties.

It was deemed wise, however, to make a

safe disposal of the prisoner Cameron. He

was accordingly dispatched under the care

of Colin Robertson, by way of Jack River,

to York Factory, to stand his trial in

England. Thus were reprisals made for the

capture and removal of Miles Macdonell in

the preceding year, both actions being of

doubtful legality. On account of the

failure of the Hudson's Bay Company ship

to leave York Factory in that year,

Cameron did not reach England for

seventeen months, where he was immediately

released.

The fall of Fort Gibraltar was soon to

follow the deportation of its commandant.

The matter of the dismantling of Fort

Gibraltar was much discussed between

Governor Semple and his lieutenant, Colin

Robertson. The latter was opposed to the

proposed destruction of the Nor'-Wester

fort, knowing the excitement such a course

would cause. However, after the departure

of Robertson to Hudson Bay in charge of

Cameron, the Governor carried out his

purpose, and in the end of May, 1816, the

buildings were pulled down. A force of

some thirty men were employed, and,

expecting as they did, a possible

interruption from the West, the work was

done in a week or a little more.

The materials were taken apart; the

stockade was made into a raft, the

remainder was piled upon it, and all was

floated down Red River to the site of Fort

Douglas. The material was then used for

strengthening the fort and building new

houses in it. Thus ended Fort Gibraltar. A

considerable establishment it was in its

time ; its name was undoubtedly a misnomer

so far as strength was concerned; yet it

points to its origination in troublous

times.

The vigorous policy carried out in regard

to Fort Gibraltar was likewise shown in

the district south of the Forks. As we

have seen, to the south, Fort Daer had

been erected, and thither, winter by

winter, the settlers had gone for

subsistence. Here, too, was the

Nor'-Wester fort of Pembina House. During

the time when Governor Semple and Colin

Robertson were maturing their plans, it

was determined to seize Pembina. No sooner

had the news of Cameron's seizure reached

Fort Daer, than Sheriff Macdonell, who was

in charge, organized an expedition, took

Pembina House, and its officers and

inhabitants. The prisoners were sent to

Fort Douglas, and were liberated on

pledges of good behaviour, and the

military stores were also taken to Fort

Douglas. The reasons given by the colony

people for this course are "self-defence

and the security of the lives of the

settlers." About the end of April, the

settlers returned from Fort Daer, and were

placed on their respective lots along the

Red River.

All events now plainly pointed to armed

disturbances and bloodshed. The policy of

Governor Semple was too vigorous when the

inflammable elements in the country were

borne in mind. There was in the country a

class called "Free Canadians," i.e. those

French Canadian trappers and traders not

connected with either Company, who

obtained a precarious living for

themselves, their Indian wives, and

half-breed children. These, fearing

trouble, betook themselves to the plains.

The Indians of the vicinity seemed to have

gained a liking for the colonists and

their leaders. When they heard the

threatenings from the West, two of the

chiefs came to Governor Semple and offered

the assistance of their bands. This the

Governor could not accept, whereat the

chiefs gave voice to their sorrow and

disappointment. Governor Semple seems to

have disregarded all these omens of coming

trouble, and to have acted almost without

common prudence. No doubt, having but

lately come to the country, he failed to

understand the daring character of his

opponents.