Lachine, the fur traders'

Mecca—The departure—The

flowing bowl— The canoe

brigade—The voyageur's

song—"En roulant ma boule"—Village

of St. Anne's—Legend of the

Church—The sailor's

guardian—Origin of "Canadian

Boat Song"—A loud

invocation—"A la Claire

Fontaine"—"Sing,

nightingale"—At the

rapids—The ominous

crosses—"Lament of Cadieux

"—A lonely maiden site—The

Wendigo—Home of the

Ermatingera— A very old

canal—The rugged coast—Fort

William reached—A famous

gathering—The joyous return.

Montreal, to-day the chief

city of Canada, was, after

the union of the Companies,

the centre of the fur trade

in the New World. The old

Nor'-Wester influence

centred on the St. Lawrence,

and while the final court of

appeal met in London, the

forces that gave energy and

effect to the decrees of the

London Board acted from

Montreal. At Lachine, above

the rapids, nine miles from

the city, lived Governor

Simpson, and many retired

traders looked upon Lachine

as the Mecca of the fur

trade. Even before the days

of the Lachine Canal, which

was built to avoid the

rapids, it is said the

pushing traders had taken

advantage of the little

River St. Pierre, which

falls into the St. Lawrence,

and had made a deep cutting

from it up which they

dragged their boats to

Lachine. To the hardy French

voyageurs, accustomed to

"portage" their cargoes up

steep cliffs, it was no

hardship to use the

improvised canal and reach

Lachine at the head of the

rapids.

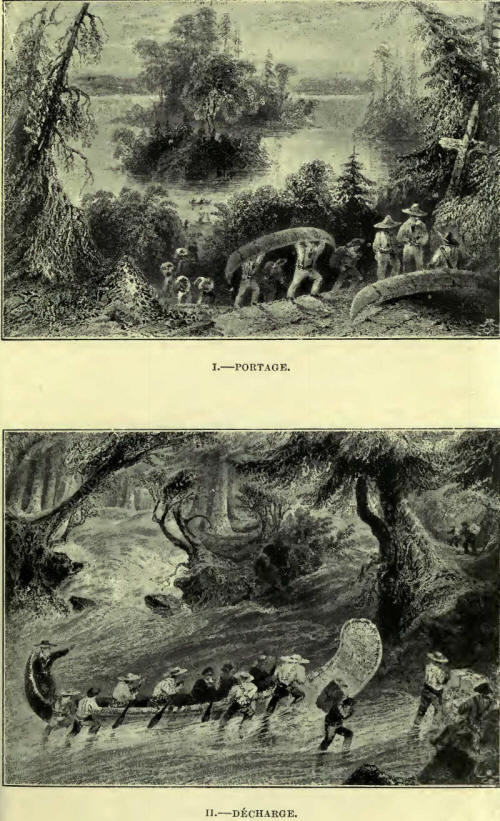

Accordingly, Lachine became

the port of departure for

the voyageurs on their long

journeys up the Ottawa, and

on to the distant fur

country. Heavy canoes

carrying four tons of

merchandise were built for

the freight, and light

canoes, some times manned

with ten or twelve men, took

the officers at great speed

along the route. The canoes

were marvels of durability.

Made of thin but tough

sheets of birch bark,

securely gummed along the

seams with pitch, they were

so strong, and yet so light,

that the Indians thought

them an object of wonder,

and said they were the gift

of the Manitou.

The voyageurs were a hardy

class of men, trained from

boyhood to the use of the

paddle. Many of them were

Iroquois Indians—pure or

with an admixture of white

blood. But the French

Canadians, too, became noted

for their expert management

of the canoe, and were

favourites of Sir George

Simpson. Like all sailors,

the voyageurs felt the day

of their departure a day of

fate. Very often they sought

to drown their sorrows in

the flowing bowl, and it was

the trick of the commander

to prevent this by keeping

the exact time of the

departure a secret, filling

up the time of the voyageurs

with plenty to do and

leaving on very short

notice. However, as the

cargo was well-nigh shipped,

wives, daughters, children,

and sweethearts too, of the

departing canoe men began to

linger about the docks, and

so were ready to bid their

sad farewells.

In the governor's or chief

factor's brigade each

voyageur wore a feather in

his cap, and if the wind

permitted it a British

ensign was hoisted on each

light canoe. Farewells were

soon over. Cheers filled the

air from those left behind,

and out from Lachine up Lake

St. Louis, an enlargement of

the St. Lawrence, the

brigade of canoes were soon

to shoot on their long

voyage. No sooner had "le

maitre" found his cargo

afloat, his officers and

visitors safely seated, than

he gave the cheery word to

start, when the men broke

out with a "chanson de

voyage." Perhaps it was the

story of the "Three Fairy

Ducks," with its chorus so

lively in French, but so

prosaic, even in the hands

of the poetic McLennan, when

translated into English as

the "Rolling Ball":—

"Derrière chez nous, il y a

un étang

(Behind the

manor lies the mere),

En

roulant ma boule. (Chorus.)

Trois beaux canards s'en

vont baignant.)

(Three

ducks bathe in its waters

clear.)

En roulant ma

boule.

Rouli, roulant,

ma boule roulant,

En

roulant, ma boule roulant,

En roulant ma boule."

And now

the paddles strike with

accustomed dash. The

voyageurs are excited with

the prospect of the voyage,

all scenes of home swim

before their eyes, and the

chorister leads off with his

story of the prince (fils du

roi) drawing near the lake,

and with his magic gun

cruelly sighting the black

duck, but killing the white

one. With falling voices the

swinging men of the canoe

relate how from the

snow-white drake his

"Life

blood falls in rubies

bright,

His diamond eyes

have lost their light,

His plumes go floating east

and west,

And form at

last a soldier's bed.

En

roulant ma boule

(Sweet

refuge for the wanderer's

head),

En roulant ma

boule,

Rouli, roulant,

ma boule roulant,

En

roulant ma boule roulant,

En roulant ma boule."

As the

brigade hies on its way, to

the right is the purplish

brown water of the Ottawa,

and on the left the green

tinge of the St. Lawrence,

till suddenly turning around

the western extremity of the

Island of Montreal, the

boiling waters of the mouth

of the Ottawa are before the

voyageurs. Since 1816 there

has been a canal by which

the canoes avoid these

rapids, but before that time

all men and officers

disembarked and the goods

were taken by portage around

the foaming waters.

And now

the village of Ste. Anne's

is reached, a sacred place

to the departing voyageurs,

and here at the old

warehouse the canoes are

moored. Among the group of

pretty Canadian houses

stands out the Gothic church

with its spire so dear an

object to the canoe men. The

superstitious voyageurs

relate that old Bréboeuf,

who had gone as priest with

the early French explorers,

had been badly injured on

the portage by the fall of

earth and stones upon him.

The attendance possible for

him was small, and he had

laid himself down to die on

the spot where stands the

church. He prayed to Ste.

Anne, the sailors' guardian,

and on her appearing to him

he promised to build a

church if he survived. Of

course, say the voyageurs,

with a merry twinkle of the

eye, ho recovered and kept

his word. At the shrine of

"la bonne Ste. Anne" the

voyageur made his vow of

devotion, asked for

protection on his voyage,

and left such gift as he

could to the patron saint.

Coming

up and down the river at

this point the voyageurs

often sang the song:—

"Dans

mon chemin j'ai rencontré

Deux cavaliers très bien

montés;"

with

the refrain to every verse:—

"A

l'ombre d'un bois je m'en

vais jouer,

A l'ombre

d'un bois je m'en vais jouer."

("Under the shady tree I

go to play.")

It is

said that it was when struck

with the movement and rhythm

of this French chanson that

Thomas Moore, the Irish

poet, on his visit to

Canada, while on its inland

waters, wrote . the

"Canadian Boat Song," and

made celebrated the good

Ste. Anne of the voyageurs.

Whether in the first lines

he succeeded in imitating

the original or not, his

musical notes are

agreeable:—

"Faintly as tolls the

evening chime,

Our

voices keep tune and our

oars keep time."

Certainly the refrain has

more of the spirit of the

boatman's song:—

"Row,

brothers, row; the stream

runs fast,

The rapids

are near and the daylight's

past."

The true colouring

of the scene is reflected in

"We'll sing at Ste. Anne;"

and—

"Uttawa's

tide, this trembling moon,

Shall see us float over

thy surges soon."

Ste.

Anne really had a high

distinction among all the

resting-places on the fur

trader's route. It was the

last point in the departure

from Montreal Island.

Religion and sentiment for a

hundred years had

consecrated it, and a short

distance above it, on an

eminence overlooking the

narrows—the real mouth of

the Ottawa—was a venerable

ruin, now overgrown with ivy

and young trees, "Chateau

brillant," a castle speaking

of border foray and Indian

warfare generations ago.

If the

party was a distinguished

one there was often a priest

included, and he, as soon as

the brigade was fairly off

and the party had settled

down to the motion,

reverently removing his hat,

sounded forth a loud

invocation to the Deity and

to a long train of male and

female saints, in a loud and

full voice, while all the

men at the end of each

versicle made response, "Qu'il

me bénisse." This done, he

called for a song. None of

the many songs of France

would be more likely at this

stage than the favourite and

most beloved of all French

Canadian songs, "A la Claire

Fontaine."

The

leader in solo would ring

out the verse—

"A la

claire fontaine,

M'en

allent promener,

J'ai

trouve l'eau si belle,

Que je m'y sois baigné."

("Unto

the crystal fountain,

For pleasure did I stray;

So fair I found the

waters,

My limbs in them

I lay.")

Then in

full chorus all would unite,

followed verse by verse.

Most touching of all would

be the address to the

nightingale—

"Chantez,

rossignol, chantez,

Toi

qui as le coeur gai;

Tu

as le coeur à rire,

Moi,

je l'ai à pleurer."

("Sing, nightingale, keep

singing,

Thou hast a

heart so gay;

Thou hast

a heart so merry,

While

mine is sorrow's prey."

The

most beautiful of all, the

chorus, is again repeated,

and is, as translated by

Lighthall:—

"Long

is it I have loved thee,

Thee shall I love alway,

My dearest;

Long is it I

have loved thee,

Thee

shall I love alway."

The

brigade swept on up the Lake

of Two Mountains, and though

the work was hard, yet the

spirit and exhilaration of

the way kept up the hearts

of the voyageurs and

officers, and as one song

was ended, another was begun

and carried through. Now it

was the rollicking chanson,

"C'est la Belle Francoise,"

then the tender "La Violette

Dandine," and when

inspiration was needed, that

song of perennial interest,

"Malbrouck s'en va-t-en

guerre."

A

distance up the Ottawa,

however, the scenery

changes, and the river is

interrupted by three

embarrassing rapids. At

Carillon, opposite to which

was Port Fortune, a great

resort for retired fur

traders, the labours began,

and so these rapids,

Carillon, Long Sault, and

Chute au Blondeau, now

avoided by canals, were in

the old days passed by

portage with infinite toil.

Up the river to the great

Chaudière, where the City of

Ottawa now stands, they

cheerfully rowed, and after

another great portage the

Upper Ottawa was faced. The

most dangerous and exacting

part of the great river was

the well-known section where

two long islands, the lower

the Calumet, and the

Allumette block the stream,

and fierce rapids are to be

encountered. This was the

piece de resistance of the

canoe-men's experience.

Around it their

superstitions clustered. On

the shores were many crosses

erected to mark the death,

in the boiling surges beside

the portage, of many

comrades who had perished

here. Between the two

islands on the north side of

the river, the Hudson's Bay

Company had founded Fort

Coulonge, used as a depot or

refuge in case of accident.

No wonder the region, with

"Deep River" above, leading

on to the sombre narrows of

"Hell Gate" further up the

stream, appealed to the fear

and imagination of the

voyageurs.

Ballad

and story had grown round

the boiling flood of the

Calumet. As early as the

time of Champlain, the story

goes that an educated and

daring Frenchman named

Cadieux had settled here,

and taken as his wife one of

the dusky Ottawas. The

prowling Iroquois attacked

his dwelling. Cadieux and

one Indian held the enemy at

bay, and firing from

different points led them to

believe that the stronghold

was well manned. In the

meantime, the spouse of

Cadieux and a few Indians

launched their canoes into

the boiling waters and

escaped. From pool to pool

the canoe was whirled, but

in its course the Indians

saw before them a female

figure, in misty robes,

leading them as protectress.

The Christian spouse said it

was the "bonne Ste. Anne,"

who led them out of danger

and saved them. The Iroquois

gave up the siege. Cadieux's

companion had been killed,

and the surviving settler

himself perished from

exhaustion in the forest.

Beside him, tradition says,

was found his death-song,

and this "Lament de Cadieux,"

with its touching and

attractive strain, the

voyageurs sang when they

faced the dangers of the

foaming currents of the

Upper Ottawa.

The

whole route, with its

rapids, whirlpools, and

deceptive currents, came to

be surrounded, especially in

superstitious minds, with an

air of dangerous mystery. A

traveller tells us that a

prominent fur trader pointed

out to him the very spot

where his father had been

swept under the eddy and

drowned. The camp-fire

stories were largely the

accounts of disasters and

accidents on the long and

dangerous way. As such a

story was told on the edge

of a shadowy forest the

voyageurs were filled with

dread. The story of the

Wendigo was an alarming one.

No crew would push on after

the sun was set, lest they

should see this apparition.

Some

said he was a spirit

condemned to wander to and

fro in the earth on account

of crimes committed, others

believed the Wendigo was a

desperate outcast, who had

tasted human flesh, and

prowled about at night,

seeking in camping-places of

the traders a victim. Tales

were told of unlucky

trappers who had disappeared

in the woods and had never

been heard of again. The

story of the Wendigo made

the camping-place to be

surrounded with a sombre

interest to the traders.

Unbelievers in this

mysterious ogre freely

declared that it was but a

partner's story told to

prevent the voyageurs

delaying on their Journey,

and to hinder them from

wandering to lonely spots by

the rapids to fish or hunt.

One of the old writers spoke

of the enemy of the

voyageurs—

"Il se

nourrit des corps des

pauvres voyageurs,

Des

malheureux passants et des

navigateurs."

("He feeds

on the bodies of unfortunate

men of the river, of unlucky

travellers, and of the

mariners.")

Impressed by the sombre

memories of this fur

traders' route, a traveller

in the light canoes in

fur-trading days, Dr. Bigsby,

relates that he had a great

surprise when, picking his

way along a rocky portage,

he "suddenly stumbled upon a

young lady sitting alone

under a bush in a green

riding habit and white

beaver bonnet." The

impressionable doctor looked

upon this forest sylph and

doubted whether she was

"One of

those fairy shepherds and

shepherdesses

Who

hereabouts live on

simplicity and watercresses."

After

confused explanations on the

part of both, the lady was

found to be an Ermatinger,

daughter of the well-known

trader of Saulte Ste. Marie,

who with his party was then

at the other end of the

portage.

We may now, with

the privilege accorded the

writer, omit the hardships

of hundreds of miles of

painful journeying, and waft

the party of the voyageurs,

whose fortunes we have been

following, up to the head of

the west branch of the

Ottawa, across the Vaz

portages, and down a little

stream into Lake Nipissing,

where there was an old-time

fort of the Nor'-Westers,

named La Ronde. Across Lake

Nipissing, down the French

River, and over the Georgian

Bay with its beautiful

scenery, the voyageurs'

brigade at length reached

the River St. Mary, soon to

rest at the famous old fort

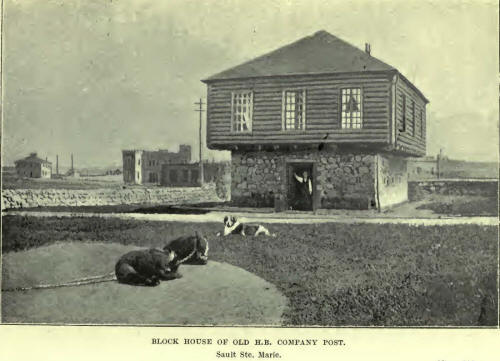

of Sault Ste. Marie. Sault

Ste. Marie was the home of

the Ermatingers, to which

the fairy shepherdess

belonged.

The

Ermatinger family, whose

name so continually

associates itself with Sault

Ste. Marie, affords a fine

example of energy and

influence. Shortly after the

conquest of Canada by Wolfe,

a Swiss merchant came from

the United States and made

Canada his home. One of his

sons, George Ermatinger,

journeyed westward to the

territory now making up

Michigan, and, finding his

way to Sault Ste. Marie,

married, engaged in the fur

trade, and died there.

Still

more noted than his brother,

Charles Oaks Ermatinger,

going westward from

Montreal, also made Sault

Ste. Marie his homo. A man

of great courage and local

influence in the war of

1812, the younger brother

commanded a company of

volunteers in the expedition

from Fort St. Joseph, which

succeeded that summer in

capturing Michilimackinac.

His fur-trading

establishment at Sault Ste.

Marie was situated on the

south side of the river,

opposite the rapids. When

this territory was taken

possession of by the troops

of the United States in

1822, the fur trader's

premises at Sault Ste. Marie

were seized and became the

American fort. For some

years after this seizure

trader Ermatinger had a

serious dispute with the

United States Government

about his property, but

finally received

compensation. True to the

Ermatinger disposition, the

trader then withdrew to the

Canadian side, retained his

British connection, and

carried on trade at Sault

Ste. Marie, Drummond Island,

and elsewhere.

A

resident of Sault Ste. Marie

informs the writer that the

family of Ermatinger about

that place is now a very

numerous one, "related to

almost all the families,

both white and red." Very

early in the century (1814),

a passing trader named

Franchère arrived from the

west country at the time

that the American troops

devastated Sault Ste. Marie.

Charles Ermatinger then had

his buildings on the

Canadian side of the river,

not far from the houses and

stores of the North-West

Company, which had been

burnt down by the American

troops. Ermatinger at the

time was living on the south

side of the river

temporarily in a house of

old trader Nolin, whose

family, the traveller tells

us, consisted of "three

half-breed boys and as many

girls, one of whom was

passably pretty." Ermatinger

had Just erected a grist

mill, and was then building

a stone house "very

elegant." To this home the

young lady overtaken by Dr.

Bigsby on the canoe route

belonged. Of the two nephews

of the doughty old trader of

Sault Ste. Marie, Charles

and Francis Ermatinger, who

were prominent in the fur

trade, more anon.

The

dashing rapids of the St.

Mary River are the natural

feature which has made the

place celebrated. The

exciting feat of "running

the rapids" is accomplished

by all distinguished

visitors to the place. John

Busheau, or some other dusky

canoe-man, with unerring

paddle, conducts the

shrinking tourist to within

a yard of the boiling

cauldron, and sweeps down

through the spray and

splash, as his passenger

heaves a sigh of relief.

The

obstruction made by the

rapids to the navigation of

the river, which is the

artery connecting the trade

of Lakes Huron and Superior,

early occupied the thought

of the fur traders. A

century ago, during the

conflict of the North-West

Company and the X Y, the

portage past the rapids was

a subject of grave dispute.

Ardent appeals were made to

the Government to settle the

matter. The X Y Company

forced a road through the

disputed river frontage,

while the North-West Company

used a canal half a mile

long, on which was built a

lock; and at the foot of the

canal a good wharf and

storehouse had been

constructed. This waterway,

built at the beginning of

the century and capable of

carrying loaded canoes and

considerable boats, was a

remarkable proof of the

energy and skill of the fur

traders.

The

river and rapids of St. Mary

past, the joyful voyageurs

hastened to skirt the great

lake of Superior, on whoso

shores their destination

lay. Deep and cold, Lake

Superior, when stirred by

angry winds, became the

grave of many a voyageur.

Few that fell into its icy

embrace escaped. Its rocky

shores were the death of

many a swift canoe, and its

weird legends were those of

the Inini-Wudjoo, the great

giant, or of the hungry

heron that devoured the

unwary. Cautiously along its

shores Jean Baptiste crept

to Michipicoten, then to the

Pic, and on to Nepigon,

places where trading posts

marked the nerve centres of

the fur trade.

At

length, rounding Thunder

Cape, Fort William was

reached, the goal of the "mangeur

de lard" or Montreal

voyageur. Around the walls

of the fort the great

encampment was made. The

River Kaministiquia was gay

with canoes ; the East and

West met in rivalry—the wild

couriers of the West and the

patient boatmen of the East.

In sight of the fort stood,

up the river, McKay

Mountain, around which

tradition had woven fancies

and tales. Its terraced

heights suggest man's work,

but it is to this day in a

state of nature. Here in the

days of conflict, when the

opposing trappers and

hunters went on their

expeditions, old Trader

McKay ascended, followed

them with his keen eye in

their meanderings, and

circumvented them in their

plans.

The

days of waiting, unloading,

loading, feasting, and

contending being over, the

Montreal voyageurs turned

their faces homeward, and

with flags afloat, paddled

away, now cheerfully singing

sweet "Alouette."

"Ma

mignonette, embrassez-moi.

Nenni, Monsieur, je

n'oserais,

Car si mon

papa le savait."

(My darling, smile on me.

No ! No ! good sir, I do not

dare,

My dear papa would

know ! would know !)

"But

who would tell papa?"

"The birds on the forest

tree."

"Ils parlent francais, latin

aussi,

Hélas! que le

monde est malin

D'apprendre aux oiseaux le

latin."

("They speak French and

Latin too,

Alas ! the

world is very bad

To

tell its tales to the

naughty birds.")

Bon voyage! Bon voyage, mos

voyageurs!