A

picturesque life—The

prairie hunters and

traders—Gaily-caparisoned

dog trains—The great

winter packets—Joy in

the lonely forts—The

summer trade—The York

boat brigade—Expert

voyageurs—The famous

Red River cart—Shagganappe

ponies— The screeching

train—Tripping—The

western cayuse—The

great buffalo

hunt—Warden of the

plains—Pemmican and

fat—the return in

triumph.

The great prairies of

Rupert's Land and

their intersecting

rivers afforded the

means for the unique

and picturesque life

of the prairie hunters

and traders. The

frozen, snowy plains

and lakes were crossed

in winter by the

serviceable sledge

drawn by Eskimo dogs,

familiarly called "Eskies"

or "Huskies." When

summer had come, the

lakes and rivers of

the prairies, formerly

skimmed by canoes,

during the fifty years

from the union of the

Companies till the

transfer of Rupert's

Land to Canada, were

for freight and even

rapid transit crossed

and followed by York

and other boats. The

transport of furs and

other freight across

the prairies was

accomplished by the

use of carts—entirely

of wood—drawn by

Indian ponies, or by

oxen in harness, while

the most picturesque

feature of the prairie

life of Red River was

the departure of the

brigade of carts with

the hunters and their

families on a great

expedition for the

exciting chase of the

buffalo. These salient

points of the prairie

life of the last

half-century of

fur-trading life we

may with profit

depict.

SLEDGE AND PACKET.

Under the regime

established by

Governor Simpson, the

communication with the

interior was reduced

to a system. The great

winter event at Red

River was the leaving

of the North-West

packet about December

10th. By this agency

every post in the

northern department

was reached. Sledges

and snowshoes were the

means by which this

was accomplished. The

sledge or tobogan was

drawn by three or four

"Huskies," gaily

comparisoned; and with

these neatly harnessed

dogs covered with

bells, the traveller

or the load of

valuables was hurried

across the pathless

snowy wastes of the

plains or over the ice

of the frozen lakes

and rivers. The dogs

carried their freight

of fish on which they

lived, each being fed

only at the close of

his day's work, and

his allowance one

fish.

The winter packet was

almost entirely

confined to the

transport of letters

and a few newspapers.

During Sir George

Simpson's time an

annual file of the

Montreal Gazette was

sent to each post, and

to some of the larger

places came a year's

file of the London

Times. A box was

fastened on the back

part of the sledge,

and this was packed

with the important

missives so prized

when the journey was

ended.

Going at the rate of

forty or more miles a

day with the precious

freight, the party

with their sledges

camped in the shelter

of a clump of trees or

bushes, and built

their camp fire; then

each in his blankets,

often joined by the

favourite dog as a

companion for heat,

sought rest on the

couch of spruce or

willow boughs for the

night with the

thermometer often at

30 deg. or 40 deg.

below zero F.

The winter packet ran

from Fort Garry to

Norway House, a

distance of 350 miles.

At this point the

packet was all

rearranged, a part of

the freight being

carried eastward to

Hudson Bay, the other

portion up the

Saskatchewan to the

western and northern

forts. The party which

had taken the packet

to Norway House, at

that point received

the packages from

Hudson Bay and with

them returned to Fort

Garry. The western

mail from Norway House

was taken by another

sledge party up the

Saskatchewan River,

and leaving parcels at

posts along the route,

reached its rendezvous

at Carlton House. The

return party from that

point received the

mail from the North,

and hastened to Fort

Garry by way of Swan

River district,

distributing its

treasures to the posts

it passed and reaching

Fort Garry usually

about the end of

February.

At Carlton a party of

runners from Edmonton

and the Upper

Saskatchewan made

rendezvous, deposited

their packages,

received the outgoing

mail, and returned to

their homes. Some of

the matter collected

from the Upper

Saskatchewan and that

brought, as we have

seen, by the inland

packet from Fort Garry

was taken by a new set

of runners to

Mackenzie River, and

Athabasca. Thus at

Carlton there met

three parties, viz.

from Fort Garry,

Edmonton, and

Athabasca. Each

brought a packet and

received another back

in return. The return

packet from Carlton to

Fort Garry, arriving

in February, took up

the accumulated

material, went with it

to Norway House, the

place whence they had

started in December,

thus carrying the "Red

River spring packet,"

and at Norway House it

was met by another

express, known as the

"York Factory spring

packet," which had

just arrived. The

runners on these

various packets

underwent great

exposure, but they

were fleet and

athletic and knew how

to act to the best

advantage in storm and

danger. They added a

picturesque interest

to the lonely life of

the ice-bound post as

they arrived at it,

delivered their

message, and again

departed.

KEEL AND CANOE.

The transition from

winter to spring is a

very rapid one on the

plains of Rupert's

Land. The ice upon the

rivers and lakes

becomes honey-combed

and disappears very

soon. The rebound from

the icy torpor of

winter to the active

life of the season

that combines spring

and summer is

marvellous. No sooner

were the waterways

open in the

fur-trading days than

freight was hurried

from one part of the

country to another by

moans of inland or

York boats.

These boats, it will

be remembered, were

introduced by Governor

Simpson, who found

them more safe and

economical than the

canoe generally in use

before his time.

Each of these boats

could carry three or

four tons of freight,

and was manned by nine

men, one of them being

steersman, the

remainder, men for the

oar. Four to eight of

these craft made up a

brigade, and the skill

and rapidity with

which these boats

could be loaded or

unloaded, carried past

a portage or decharge,

guided through rapids

or over considerable

stretches of the

lakes, was the pride

of their Indian or

half-breed tripsmen,

as they were called,

or the admiration of

the officers dashing

past them in their

speedy canoes.

The route from York

Factory to Fort Garry

being a long and

continuous waterway,

was a favourite course

for the York boat

brigade. Many of the

settlers of the Red

River settlement

became well-to-do by

commanding brigades of

boats and carrying

freight for the

Company. In the

earlier days of

Governor Simpson the

great part of the furs

from the interior were

carried to Fort Garry

or the Grand Portage,

at the mouth of the

Saskatchewan, and

thence past Norway

House to Hudson Bay.

From York Factory a

load of general

merchandise was

brought back, which

had been cargo in the

Company's ship from

the Thames to York.

Lake Winnipeg is

generally clear of ice

early in June, and the

first brigade would

then start with its

seven or eight boats

laden to the gunwales

with furs; a week

after, the second

brigade was under way,

and thus, at intervals

to keep clear of each

other in crossing the

portages, the catch of

the past season was

carried out. The

return with full

supplies for the

settlers was earnestly

looked for, and the

voyage both ways,

including stoppages,

took some nine weeks.

Far up into the

interior the goods in

bales were taken. One

of the best known

routes was that of

what was called, "The

Portage Brigade." This

ran from Lake Winnipeg

up the Saskatchewan

northward, past

Cumberland House and

Ile a la Crosse to

Methy Portage,

otherwise known as

Portage la Loche,

where the waters part,

on one side going to

Hudson's Bay, on the

other flowing to the

Arctic Sea. The trip

made from Fort Garry

to Portage la Loche

and return occupied

about four months. At

Portage la Loche the

brigade from the

Mackenzie River

arrived in time to

meet that from the

south, and was itself

soon in motion,

carrying its year's

supply of trading

articles for the Far

North, not even

leaving out Peel's

River and the Yukon.

The frequent

transhipments required

in these long and

dangerous routes led

to the secure packing

of bales, of about one

hundred pounds each,

each of them being

called an "inland

piece." Seventy-five

made up the cargo of a

York boat. The skill

with which these boats

could be laden was

surprising. A good

half-breed crew of

nine men was able to

load a boat and pack

the pieces securely in

five minutes.

The

boat's crew was under

the command of the

steersman, who sat on

a raised platform in

the stern of the boat.

At the portages it was

the part of the

steersman to raise

each piece from the

ground and place two

of them on the back of

each tripsman, to be

held in place by the

"portage strap" on the

forehead. It will be

seen that the position

of the captain was no

sinecure. One of the

eight tripsmen was

known as "bows-man."

In running rapids he

stood at the bow, and

with a light pole

directed the boat,

giving information by

word and sign to the

steersman. The

position of less

responsibility though

great toil was that of

the "middlemen," or

rowers. When a breeze

blew, a sail hoisted

in the boat lightened

their labours. The

captain or steersman

of each boat was

responsible to the

"guide," who, as a

commander of the

brigade, was a man of

much experience, and

consequently held a

position of some

importance. Such were

the means of transport

over the vast water

system of Rupert's

Land up to the year

1869, although some

years before that time

transport by land to

St. Paul in Minnesota

had reached large

proportions. Since the

date named, railway

and steamboat have

directed trade into

new channels, for even

Mackenzie River now

has a Hudson's Bay

Company steamboat.

CART AND CAYUSE.

The lakes and rivers

were not sufficient to

carry on the trade of

the country.

Accordingly, land

transport became a

necessity. If the

Ojibeway Indians found

the birch bark canoe

and the snowshoe so

useful that they

assigned their origin

to the Manitou, then

certainly it was a

happy thought when the

famous Rod River cart

was similarly evolved.

These two-wheeled

vehicles are entirely

of wood, without any

iron whatever.

The wheels are large,

being five feet in

diameter, and are

three inches thick.

The felloes are

fastened to one

another by tongues of

wood, and pressure in

revolving keeps them

from falling apart.

The hubs are thick and

very strong. The axles

are wood alone, and

even the lynch pins

are wooden. A light

box frame, tightened

by wooden pegs, is

fastened by the same

agency and poised upon

the axle. The price of

a cart in Red River of

old was two pounds.

The harness for the

horse which drew the

cart was made of

roughly-tanned ox

hide, which was

locally known as "shagganappe."

The name "shagganappe"

has in later years

been transferred to

the small-sized horse

used, which is thus

called a "shagganappe

pony."

The carts were drawn

by single ponies, or

in some cases by

stalwart oxen. These

oxen were harnessed

and wore a collar, not

the barbarous yoke

which the ox has borne

from time immemorial.

The ox in harness has

a swing of majesty as

he goes upon his

journey. The Indian

pony, with a load of

four or five hundred

pounds in a cart

behind him, will go at

a measured jog-trot

fifty or sixty miles a

day. Heavy freighting

carts made a journey

of about twenty miles

a day, the load being

about eight hundred

pounds.

A train of carts of

great length was

sometimes made to go

upon some long

expedition, or for

protection from the

thievish or hostile

bands of Indians. A

brigade consisted of

ten carts, under the

charge of three men.

Five or six more

brigades were joined

in one train, and this

was placed under the

charge of a guide, who

was vested with much

authority. He rode on

horseback forward,

marshalling his

forces, including the

management of the

spare horses or oxen,

which often amounted

to twenty per cent. of

the number of those

drawing the carts. The

stopping-places,

chosen for good grass

and a plentiful supply

of water, the time of

halting, the

management of

brigades, and all the

details of a

considerable camp were

under the care of this

officer-in-chief.

One of the most

notable cart trails

and freighting roads

on the prairies was

that from Fort Garry

to St. Paul,

Minnesota. This was an

excellent road, on the

west side of the Red

River, through Dakota

territory for some two

hundred miles, and

then, by crossing the

Red River into

Minnesota, the road

led for two hundred

and fifty miles down

to St. Paul. The

writer, who came

shortly after the

close of the fifty

years we are

describing, can

testify to the

excellence of this

road over the level

prairies. At the

period when the Sioux

Indians were in revolt

and the massacre of

the whites took place

in 1862, this route

was dangerous, and the

road, though not so

smooth and not so dry,

was followed on the

east side of the Red

River.

Every season about

three hundred carts,

employing one hundred

men, departed from

Fort Garry to go upon

the "tip," as it was

called, to St. Paul,

or in later times to

St. Cloud, when the

railway had reached

that place. The visit

of this band coming

from the north, with

their wooden carts,

"shag-ganappe" ponies,

and harnessed oxen,

bringing huge bales of

precious furs,

awakened great

interest in St. Paul.

The late J. W. Taylor,

who for about a

quarter of a century

held the position of

American Consul at

Winnipeg, and who, on

account of his

interest in the

North-West prairies,

bore the name of

"Saskatchewan Taylor,"

was wont to describe

most graphically the

advent, as he saw it,

of this strange

expedition, coming,

like a Midianitish

caravan in the East,

to trade at the

central mart. On

Sundays they encamped

near St. Paul. There

was the greatest

decorum and order in

camp; their religious

demeanour, their

honest and well-to-do

appearance, and their

peaceful disposition

were an oasis in the

desert of the wild and

reckless inhabitants

of early Minnesota.

Another notable route

for carts was that

westward from Fort

Garry by way of Fort

Ellice to Carlton

House, a distance of

some five hundred

miles. It will be

remembered that it was

by this route that

Governor Simpson in

early days, Palliser,

Milton, and Cheadle

found their way to the

West. In later days

the route was extended

to Edmonton House, a

thousand miles in all.

It was a whole

summer's work to make

the trip to Edmonton

and return.

On the Hudson's Bay

Company reserve of

five hundred acres

around Fort Garry was

a wide camping-ground

for the "trippers" and

traders. Day after day

was fixed for the

departure, but still

the traders lingered.

After much

leave-taking, the

great train started.

It was a sight to be

remembered. The gaily-comparisoned

horses, the hasty

farewells, the hurry

of women and children,

the multitude of dogs,

the balky horses, the

subduing and

harnessing and

attaching of the

restless ponies, all

made it a picturesque

day. The train in

motion appealed not

only to the eye, but

to the ear as well,

the wooden axles

creaked, and the

creaking of a train

with every cart

contributing its

dismal share, could be

heard more than a mile

away. In the Far-West

the early traders used

the cayuse, or Indian

pony, and "travoie,"

for transporting

burdens long

distances. The "travoie"

consisted of two stout

poles fastened

together over the back

of the horse, and

dragging their lower

ends upon the ground.

Great loads—almost

inconceivable,

indeed—were thus

carried across the

pathless prairies. The

Red River cart and the

Indian cayuse were the

product of the needs

of the prairies.

PLAIN HUNTERS AND THE

BUFFALO.

A generation had

passed since the

founding of the

Selkirk settlement,

and the little handful

of Scottish settlers

had become a community

of five thousand. This

growth had not been

brought about by

immigration, nor by

natural increase, but

by what may be called

a process of

accretion. Throughout

the whole of Rupert's

Land and adjoining

territories the

employes of the

Company, whether from

Lower Canada or from

the Orkney Islands, as

well as the clerks and

officers of the

country, had

intermarried with the

Indian women of the

tribes.

When the trader or

Company's servant had

gained a competence

suited to his ideas,

he thought it right to

retire from the active

fur trade and float

down the rivers to the

settlement, which the

first Governor of

Manitoba called the

"Paradise of Red

River." Here the

hunter or officer

procured a strip of

land from the Company,

on it erected a house

for the shelter of his

"dusky race," and

engaged in

agriculture, though

his former life

largely unfitted him

for this occupation.

In this way,

four-fifths of the

population of the

settlement were

half-breeds, with

their own traditions,

sensibilities, and

prejudices —the one

part of them speaking

French with a dash of

Cree mixed with it,

the other English

which, too, had the

form of a Red River

patois.

We have seen that

tripping and hunting

gave a livelihood to

some, if not the great

majority, but these

occupations unfitted

men for following the

plough. In addition

there was no market

for produce, so that

agriculture did not in

general thrive. One of

the favourite features

of Red River, which

fitted in thoroughly

with the roving

traditions of the

large part of the

population, was the

annual buffalo hunt,

which, for those who

engaged in it,

occupied a great

portion of the summer.

We have the personal

reminiscences of the

hunt by Alexander

Ross, sometime sheriff

of Assiniboia, which,

as being lively and

graphic, are worthy of

being reproduced.

Ross says: 'Buffalo

hunting here, like

bear baiting in India,

has become a popular

and favourite

amusement among all

classes; and Red

River, in consequence,

has been brought into

some degree of notice

by the presence of

strangers from foreign

countries. We are now

occasionally visited

by men of science as

well as men of

pleasure. The war road

of the savage and the

solitary haunt of the

bear have of late been

resorted to by the

florist, the botanist,

and the geologist; nor

is it uncommon

nowadays to see

officers of the

Guards, knights,

baronets, and some of

the higher nobility of

England and other

countries coursing

their steeds over the

boundless plains and

enjoying the pleasures

of the chase among the

half-breeds and

savages of the

country. Distinction

of rank is, of course,

out of the question,

and at the close of

the adventurous day

all squat down in

merry mood together,

enjoying the social

freedom of equality

round Nature's table

and the novel treat of

a fresh buffalo steak

served up in the style

of the country, that

is to say, roasted on

a forked stick before

the fire; a keen

appetite their only

sauce, cold water

their only beverage.

Looking at this

assemblage through the

medium of the

imagination, the mind

is led back to the

chivalric period of

former days, when

chiefs and vassals

took counsel together.

. . .

"With the earliest

dawn of spring the

hunters are in motion

like bees, and the

colony in a state of

confusion, from their

going to and fro, in

order to raise the

wind and prepare

themselves for the

fascinating enjoyments

of hunting. It is now

that the Company, the

farmers, the petty

traders are all beset

by their incessant and

irresistible

importunities. The

plain mania brings

everything else to a

stand. One wants a

horse, another an axe,

a third a cart; they

want ammunition, they

want clothing, they

want provisions; and

though people refuse

one or two they cannot

deny a whole

population, for,

indeed, over-much

obstinacy would not be

unattended with risk.

Thus the settlers are

reluctantly dragged

into profligate

speculation.

"The plain hunters,

finding they can get

whatever they want

without ready money,

are led into ruinous

extravagances; but the

evil of the long

credit system does not

end here. . . . So

many temptations, so

many attractions are

held out to the

thoughtless and giddy,

so fascinating is the

sweet air of freedom,

that even the

offspring of the

Europeans, as well as

natives, are often

induced to cast off

their habits of

industry and leave

their comfortable

homes to try their

fortunes in the

plains.

"The practical result

of all this may be

stated in a few words.

After the expedition

starts there is not a

man-servant or

maidservant to be

found in the colony.

At any season but

seedtime and

harvest-time, the

settlement is

literally swarming

with idlers; but at

these urgent periods

money cannot procure

them.

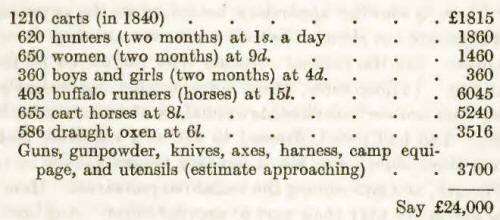

"The actual money

value expended on one

trip, estimating also

their lost time, is as

follows:—

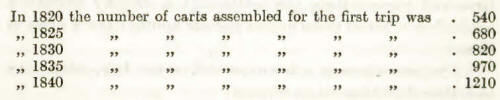

"From Fort Garry, June

15th, 1840, the

cavalcade and

followers went

crowding on to the

public road, and

thence, stretching

from point to point,

till the third day in

the evening, when they

reached Pembina (sixty

miles south of Fort

Garry), the great

rendezvous on such

occasions. When the

hunters leave the

settlement it enjoys

that relief which a

person feels on

recovering from a long

and painful sickness.

Here, on a level

plain, the whole

patriarchal camp

squatted down like

pilgrims on a journey

to the Holy Land in

ancient days, only not

quite so devout, for

neither 6crip nor

staff were consecrated

for the occasion. Here

the roll was called

and general muster

taken, when they

numbered on this

occasion 1,630 souls;

and hero the rules and

regulations for the

journey were finally

settled. The officials

for the trip were

named and installed

into office, and all

without the aid of

writing materials.

"The camp occupied as

much ground as a

modern city, and was

formed in a circle.

All the carts were

placed side by side,

the trams outward.

Within this line of

circumvallation, the

tents were placed in

double, treble rows,

at one end, the

animals at the other,

in front of the tents.

This is the order in

all dangerous places,

but where no danger is

apprehended, the

animals are kept on

the outside. Thus the

carts formed a strong

barrier, not only for

securing the people

and their animals

within, but as a place

of shelter and defence

against an attack of

the enemy from

without.

"There is another

appendage belonging to

the expedition, and

these are not always

the least noisy, viz.

the dogs or camp

followers. On the

present occasion they

numbered no fewer than

542. In deep snow,

where horses cannot

conveniently be used,

dogs are very

serviceable animals to

the hunters in these

parts. The half-breed,

dressed in his wolf

costume, tackles two

or three sturdy curs

into a flat sled,

throws himself on it

at full length, and

gets among the buffalo

unperceived. Here the

bow and arrow play

their part to prevent

noise. And here the

skilful hunter kills

as many as he pleases,

and returns to camp

without disturbing the

band.

"But now to the camp

again—the largest of

the kind, perhaps, in

the world. The first

step was to hold a

council for the

nomination of chiefs

or officers for

conducting the

expedition. Ten

captains were named,

the senior on this

occasion being Jean

Baptiste Wilkie, an

English half-breed,

brought up among the

French, a man of good

sound sense and long

experience, and withal

a fine, bold-looking,

and discreet fellow, a

second Nimrod in his

way.

"Besides being

captain, in common

with the others, he

was styled the great

war chief or head of

the camp, and on all

public occasions he

occupied the place of

president. All

articles of property

found without an owner

were carried to him

and he disposed of

them by a crier, who

went round the camp

every evening, were it

only an awl. Each

captain had ten

soldiers under his

orders, in much the

same way as policemen

are subject to the

magistrate. Ten guides

were likewise

appointed, and here we

may remark that people

in a rude state of

society, unable either

to read or write, are

generally partial to

the number ten. Their

duties were to guide

the camp each in his

turn—that is day

about—during the

expedition. The camp

flag belongs to the

guide of the day; he

is therefore standard

bearer in virtue of

his office.

"The hoisting of the

flag every morning is

the signal for raising

camp. Half an hour is

the full time allowed

to prepare for the

march ; but if anyone

is sick or their

animals have strayed,

notice is sent to the

guide, who halts till

all is made right.

From the time the flag

is hoisted, however,

till the hour of

camping arrives it is

never taken down. The

flag taken down is a

signal for encamping.

While it is up the

guide is chief of the

expedition. Captains

are subject to him,

and the soldiers of

the day are his

messengers; he

commands all. The

moment the flag is

lowered his functions

cease, and the

captains and soldiers'

duties commence. They

point out the order of

the camp, and every

cart as it arrives

moves to its appointed

place. This business

usually occupies about

the same time as

raising camp in the

morning; for

everything moves with

the regularity of

clockwork.

"All being ready to

leave Pembina, the

captains and other

chief men hold another

council and lay down

the rules to be

observed during the

expedition. Those made

on the present

occasion were:—

(1) No buffalo to be

run on the Sabbath

day.

(2) No party

to fork off, lag

behind, or go before,

without permission.

(3) No person or

party to run buffalo

before the general

order.

(4) Every

captain with his men

in turn to patrol the

camp and keep guard.

(5) For the first

trespass against these

laws, the offender to

have his saddle and

bridle cut up.

(6)

For the second offence

the coat to be taken

off the offender's

back and to be cut up.

(7) For the third

offence the offender

to be flogged.

(8)

Any person convicted

of theft, even to the

value of a sinew, to

be brought to the

middle of the camp,

and the crier to call

out his or her name

three times, adding

the word 'Thief' at

each time.

"On the 21st the start

was made, and the

picturesque line of

march soon stretched

to the length of some

five or six miles in

the direction of

south-west towards

Cote à Pique. At 2

p.m. the flag was

struck, as a signal

for resting the

animals. After a short

interval it was

hoisted again, and in

a few minutes the

whole line was in

motion, and continued

the route till five or

six o'clock in the

evening, when the flag

was hauled down as a

signal to encamp for

the night. Distance

travelled, twenty

miles.

"The camp being

formed, all the

leading men,

officials, and others

assembled, as the

general custom is, on

some rising ground or

eminence outside the

ring, and there

squatted themselves

down, tailor-like, on

the grass in a sort of

council, each having

his gun, his smoking

bag in his hand, and

his pipe in his mouth.

In this situation the

occurrences of the day

were discussed, and

the line of march for

the morrow agreed

upon. This little

meeting was full of

interest, and the fact

struck me very

forcibly that there is

happiness and pleasure

in the society of the

most illiterate men,

sympathetically if not

intellectually

inclined, as well as

among the learned, and

I must say I found

less selfishness and

more liberality among

these ordinary men

than I had been

accustomed to find in

higher circles. Their

conversation was free,

practical, and

interesting, and the

time passed on more

agreeably than could

bo expected among such

people, till we

touched on politics.

"Of late years the

field of chase has

been far from Pembina,

and the hunters do not

so much as know in

what direction they

may find the buffalo,

as those animals

frequently shift their

ground. It is a mere

leap in the dark,

whether at the outset

the expedition takes

the right or the wrong

road; and their luck

in the chase, of

course, depends

materially on the

choice they make. The

year of our narrative

they travelled a

south-west or middle

course, being the one

generally preferred,

since it leads past

most of the rivers

near their sources,

where they are easily

crossed. The only

inconvenience

attending this choice

is the scarcity of

wood, which in a warm

season is but a

secondary

consideration.

"Not to dwell on the

ordinary routine of

each day's journey, it

was the ninth day from

Pembina before we

reached the Cheyenne

River, distant only

about 150 miles, and

as yet we had not seen

a single band of

buffalo. On July 3rd,

our nineteenth day

from the settlement,

and at a distance of

little more than 250

miles, we came in

sight of our destined

hunting grounds, and

on the day following

we had our first

buffalo race. Our

array in the field

must have been a grand

and imposing one to

those who had never

seen the like before.

No less than 400

huntsmen, all mounted,

and anxiously waiting

for the word 'Start!'

took up their position

in a line at one end

of the camp, while

Captain Wilkie, with

his spyglass at his

eye, surveyed the

buffalo, examined the

ground, and issued his

orders. At eight

o'clock the whole

cavalcade broke

ground, and made for

the buffalo; first at

a slow trot, then at a

gallop, and lastly at

full speed. Their

advance was over a

dead level, the plain

having no hollow or

shelter of any kind to

conceal their

approach. We need not

answer any queries as

to the feeling and

anxiety of the camp on

such an occasion. When

the horsemen started

the cattle might have

been a mile and a half

ahead, but they had

approached to within

four or five hundred

yards before the bulls

curved their tails or

pawed the ground. In a

moment more the herd

took flight, and horse

and rider are

presently seen

bursting in among

them. Shots are heard,

and all is smoke,

dash, and hurry. The

fattest are first

singled out for

slaughter, and in less

time than we have

occupied with the

description, a

thousand carcases

strew the plain.

"The moment the

animals take to flight

the best runners dart

forward in advance. At

this moment a good

horse is invaluable to

his owner, for out of

the 400 on this

occasion, not above

fifty got the first

chance of the fat

cows. A good horse and

an experienced rider

will select and kill

from ten to twelve

animals at one heat,

while inferior horses

are contented with two

or three. But much

depends on the nature

of the ground. On this

occasion the surface

was rocky, and full of

badger holes.

Twenty-three horses

and riders were at one

moment sprawling on

the ground. One horse,

gored by a bull, was

killed on the spot,

two men disabled by

the fall. One rider

broke his shoulder

blade; another burst

his gun and lost throe

of his fingers by the

accident; and a third

was struck on the knee

by an exhausted ball.

These accidents will

not be thought

over-numerous

considering the

result; for in the

evening no less than.

1,375 buffalo tongues

wore brought into

camp.

"The rider of a good

horse seldom fires

till within three or

four yards of his

object, and never

misses. And, what is

admirable in point of

training, the moment

the shot is fired his

steed springs on one

side to avoid

stumbling over the

animal, whereas an

awkward and shy horse

will not approach

within ten or fifteen

yards, consequently

the rider has often to

fire at random and not

infrequently misses.

Many of them, however,

will fire at double

that distance and make

sure of every shot.

The mouth is always

full of balls; they

load and fire at the

gallop, and but seldom

drop a mark, although

some do to designate

the animal.

"Of all the operations

which mark the

hunter's life and are

essential to his

ultimate success, the

most perplexing,

perhaps, is that of

finding out and

identifying the

animals he kills

during a race. Imagine

400 horsemen entering

at full speed a herd

of some thousands of

buffalo, all in rapid

motion. Riders in

clouds of dust and

volumes of smoke which

darken the air,

crossing and

recrossing each other

in every direction;

shots on the right, on

the left, behind,

before, here, there,

two, three, a dozen at

a time, everywhere in

close succession, at

the same moment.

Horses stumbling,

riders falling, dead

and wounded animals

tumbling here and

there, one over the

other; and this zigzag

and bewildering melee

continued for an hour

or more together in

wild confusion. And

yet, from practice, so

keen is the eye, so

correct the judgment,

that after getting to

the end of the race,

he can not only toll

the number of animals

which he had shot

down, but the position

in which each lies—on

the right or on the

left side—the spot

where the shot hit,

and the direction of

the ball; and also

retrace his way, step

by step, through the

whole race and

recognize every animal

he had the fortune to

kill, without the

least hesitation or

difficulty. To divine

how this is

accomplished bewilders

the imagination.

"The main party

arrived on the return

journey at Pembina on

August 17th, after a

journey of two months

and two days. In due

time the settlement

was reached, and the

trip being a

successful one, the

returns on this

occasion may be taken

as a fair annual

average. An

approximation to the

truth is all we can

arrive at, however.

Our estimate is nine

hundred pounds weight

of buffalo meat per

cart, a thousand being

considered the full

load, which gives one

million and

eighty-nine thousand

pounds in all, or

something more than

two hundred pounds

weight for each

individual, old and

young, in the

settlement. As soon as

the expedition

arrived, the Hudson's

Bay Company, according

to usual custom,

issued a notice that

it would take a

certain specified

quantity of

provisions, not from

each fellow that had

been on the plains,

but from each old and

recognized hunter. The

established price at

this period for the

three kinds over head,

fat, pemmican, and

dried meat, was two

pence a pound. This

was then the Company's

standard price; but

there is generally a

market for all the fat

they bring. During the

years 1839, 1840, and

1841, the Company

expended five thousand

pounds on the purchase

of plain provisions,

of which the hunters

got last year the sum

of twelve hundred

pounds, being rather

more money than all

the agricultural class

obtained for their

produce in the same

year. It will be

remembered that the

Company's demand

affords the only

regular market or

outlet in the Colony,

and, as a matter of

course, it is the

first supplied."