Our thanks to Norman

James Williamson for this article

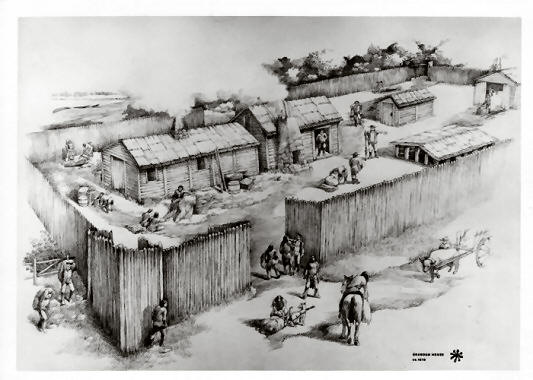

Brandon House circa 1810

Introduction: master and man

During the long

desperate struggle between the laborers and capitalists who were

making themselves rich in the British Isles at the end of the

eighteenth, century capital's most potent weapon was the statutes of

English law which prevailed throughout Great Britain and the English

Colonies at the time. These were laws which the middle class

mercantile capitalists had bought with the bribery of the old English

ruling elite.

In the English Empire this status quo was

maintained through out the country’s history by three anchors; the

navy press gang, the over supply of Irish labour and cheap gin.

When Orkneymen working in

the English colony of Rupert’s land in “British” North America carried

on a short struggle for a just return for their labour the capitalist

interest there, being the joint stock company called the Hudson’s Bay

Company, used those laws and physical intimidation to break that

workmen’s combination.

With the aid of the ambitions of a prominent

British North American plantation owner, one Thomas Douglas, this

company was able to use the English statutes to destroy any attempt to

organize the labour force in Rupertsland.

In my study of the following

events which led to the labour dispute the company called a 'mutiny'

and the means by which the company broke the combination of the

workmen involved I believe I uncovered many of the fundamental

problems of those early rudimentary unions.

It was the distinctive

relationship between master and man under English law which dominated

the position of labour in the fur trade.

Within that relationship

wide reaching decisions concerning working conditions were made by the

governing committee of the company on the basis of their English

social and racial prejudices. Prejudices, which were then taken up as

their own by the company officers, both English and non English, but

especially by the so called lowland Scots among them.

When the men of the Orkney

Islands made up the majority of the workmen, or servants [1] as they

were called, they were particularly subjected to that racial bias.

This tendency to social and racial bias on the part of the committee

members who were all either part of the upper mercantile class, landed

aristocracy or international bankers, was a major contributing factor

to the chaos in the work place that preceded the attempt at a

combination of workmen at Brandon House, the site of the “mutiny".

Historically speaking, those

who sought to make decisions concerning Orkney workmen did so on the

basis of character and looked to Murdock MacKenzie’s 1750 publication

of A Survey of The Orkney and Lewis Island [2] for their

justification.

As for the validity of the committee's action

Rich, the editor of the Hudson’s Bay Record Society, conceded that the

committee, who used the stereotype in decision making,

“were mostly

businessmen...of narrow experience and [were] regarding the American

scene from a remote and very comfortable distance.” [3]

It was

unfortunate that many of the scholars who study the company tend to

separate the "American" from the "European, scene because this

distorts the reality of the master and man relationship at that time

in history.

In fact, the social distance between the

committee members and the labourers at Brandon House was no greater

than that between the same committee members and the labourers in the

company warehouses in England.

I could not let geographic distance be confused

with the actual differences in economic power and political influence

which were at the heart of the matter. Nor could I loose sight of the

fact that the operations of the company in Rupertsland were an

inseparable, if small, part of the British economy.

In my own studies in

anthropology and history I had noted that a group upon whom a

stereotype has been fixed will sometimes assume that model when it

suited their purpose to do so.

Orkneymen did, at times,

assume some of the more positive aspects of the stereotype as a

standard of respectability when petitioning their masters. William

Yorston one of the labourers at Brandon House, for example assumed

such a stance when he finally petitioning the company for his back

wages. [4]

While there was clearly no real cultural or

biological evidence that the workmen of the Orkneys fitted the

Hudson’s Bay Company paradigm of them, there was strong evidence that

there was a ambivalent attitude towards the company among the workers.

Those attitudes were best portrayed in an anecdote recorded by Thomas

Johnston in The History of the Working Classes in Scotland:

At Ballindalloch on the

Spey, a poor man had been sentenced to death, and the gallows not

being ready he was put in the baron's pit while the scaffold was being

erected. At length everything was in order, and the baron's men called

upon the prisoner to come up; but instead of coming up the doomed man

drew a sword and threatened to slay the first individual who came down

for him. Persuasion and threat were equally unavailing, until at last,

the victim's wife appeared and cried, "Come up quietly and be hanget,

Donal', and dinna anger the laird. [5]

Because of this ambivalence

among the workers, at no time during the period of the unrest was the

entire work force affected able to unite within the combination.

Some like William Yorston found themselves torn between his attitudes

of servitude and rebellion. At once, he was a good servant and a

servant betrayed by his master.

It was this ambivalence in

the workmen's attitude towards the company and its officers that would

do as much to destroy the combination as did the manipulations of the

officers of the company.

The European

Historical Background to Brandon House Mutiny.

In order to comprehend the

situation of a labourer at Brandon in North America I first had to

turn a moment to European History in general and to Scottish history

in particular.

The turbulence in which the Scottish, working

class found itself in the first decade of the nineteenth, century was

due to two changes in land tenure and usage the clearances and

enclosures. Although by no means blameless in their treatment of the

clansmen before the defeat at Culloden in 1746, that loss definitively

turned the Scottish lairds into English landlords who were totally

inconsiderate of the welfare of the clansmen they abandoned for middle

class English gentility.

These over-lords began the

general depopulation of the Highlands in 1762. [6]

Euphemistically called a progressive agrarian revolution it included

enclosure of the common lands. Then with the advent of the Napoleonic

wars enclosure was made a matter of English patriotism by the landed

gentry [7] as they forced more and more landless men into the English

Empire’s war machine.

Traditionally the Orkneymen had drawn lots for

the parcels of land in their run rig agricultural system. They like

the Highlanders watched the unfolding events with apprehension.

In 1801

three thousand tenant farmers were evicted from Inverness shire. By

1808 they had been replaced by 50,000 sheep. [8]

On

Whitsun, in 1807, the “bitch” started her Sutherland clearance of

25,000 Highlanders.

Many of these would be picked up and used by

Selkirk and the Hudson’s bay Company to create a consistent oversupply

of labour in Rupertsland.

The clearances and closures

brought drastic changes to the prospects of the young of the labouring

classes. Cunningham pointed out:

the labourers' condition was

changed for the worse by the extinction of small farms; in the old

days there had always been a possibility that he might become an

independant farmer, but he was practically precluded from obtaining

such, capital as was requisite for working a large farm. He was thus

cut off from any hope of bettering himself, or becoming his own

master;. [10]

The ultimate result was a growing landless

underclass whose survival depended upon an earned wage. [11]

In the

Orkney Islands the workmen had three choices; first the mills and

collieries of the south, second the deep sea fleets fishing or the

navy, and third, service in the fur trade.

In the collieries of Britain

there was a growing agitation for better conditions which would

develop into rudimentary unions. In order to overcome the threat these

organizations posed to high profits, the capital controlled Parliament

passed laws which made it illegal to combine for economic purposes.

By "Section IV of the Act, any person could be punished for attending

a meeting designed for the purpose of raising wages...” [12]

As it was passed in 1800 by

the English government this law forced workers brought to trial to

give evidence against themselves a procedure that ran contrary to the

custom of English law.

With the advent of the Napoleonic wars the

conditions of the working classes in general grew worse. [13]

It was

the economic uncertainty of the land based labour market that led most

able bodied Orkneymen to choose employment at sea, [14] either in the

Greenland fishing fleets or the Royal Navy.

However,

not all of the workmen could meet the minimum standards of the fleets

or even the army.

Failing to find employment led to a world of

poor housing, disease, and death at an early age.[15] That only left

the desperate service in the Hudson’s Bay Company[16] and that joint

stock company expected that their desperation would make them

excellent servants.

The Working Conditions at Brandon House

I found that in 1810 the

workmen at Brandon House were a mixed group of long service veterans

who knew that they faced a return to an uncertain economy if they left

the company or were ejected from the company, and along side these

were men in their first or second three year agreement who had joined

the service after working conditions in Scotland had become

particularly bad.

However, in spite of the danger entailed in

getting into a labour dispute with the company, men from both these

categories were involved in the combination at Brandon House. That was

because the working conditions created by the company committee had

become intolerable at the post.

When I undertook to look

into those working conditions at Brandon House the first thing I noted

was the pall of death that permeated the fur trade.

The root

cause of that mortality was the company’s trade in alcohol. Even

officers whose particular personalities brought them advancement in

the company begged God's forgiveness for the trade in spirits. [17]

There were many notations in

the Post Journals that I read that attested to the consequence of the

trade in alcohol:

April 3 All my Indians fell a fighting two of

them were killed and 3 wounded. This is a pretty affair I will loose

all my debts.[18]

As noted diligent officers of the company kept

their priorities correct, especially when reporting to their masters

and what mattered to the company first and foremost was profit.

However

for the servants at Brandon House the danger was more immediate:

Feb. 10 William Yorston and

George Henderson brot (sic) letters from Mr. Miller also informs me of

ye death of Mr. John Linklater who was stabed by an Indian when

drunk.[19]

The two servants who brought, this intelligence

to the master of Brandon House in 1800 would both play major roles in

the events of 1810.

In addition to the dangers of the violence

caused by the alcohol among the Indians the workmen were also in

constant danger from The tribal warfare [20] in which battles,

although small in magnitude, were quite often fought near the post.

[21]

Furthermore servants caught out on the plains

were subject to attack by the raiding Indian parties from outside the

district:

Aug. 19 Easter and men returned from hunting

with the meat of two bull they could not get where the cows were on

account of the enemy forty of whom, perused them about seven hours,

they may thank their good horses that their heads were not turned into

footballs. [22]

These particular enemies had been the Gros

ventre and Easter, by the way was an unpaid Eskimo slave of the

Honorable company.

The year following this event one of the

servants was shot in the neck with, an iron shod arrow, [23]

From the very onset of the

establishment of the inland posts by the company the workmen had been

reluctant to go inland to posts like Brandon House. [24]

That reluctance was due to

the fact that the wages had to be agreed upon before assignment

regardless of where the labourer was going to be sent.

This was done in order to

keep wage demands low as a posting to the inland posts meant harder

work and more danger than posting to the bay shore factories.

Therefore every year men who “agreed" at the same time for the same

wages as their compatriots at Albany House on Hudson’s Bay found

themselves posted inland to Brandon.

Many of these servants had

to be forced to go inland by threat of punishment for disobedience if

they did not. Much of the so called sullenness recorded by company

officers was due to this practice.

Over a period of years

veteran Factors like Hodgson, Chief at Albany had learned to maintain

a balance between a relatively acquiescent work force and profit at

his inland posts by the use of a number of wage supplementals and a

less stringent work load.

A simple but highly

effective supplemental was the practice of providing the servants in

the interior with a decent share of the imported food like beef, pork

and flour, which, were termed English provisions and were a reminder

of home.

Further, he saw to it that they were given

extensive access to the country victuals such as buffalo meat,

pemmican and other game at the inland posts.

As the

English company never provided any inland post with sufficient

imported food for the men to survive a winter the men's lives depended

upon the hunting of game.

When the over killing of

local stocks or natural fluctuation of population reduced the amount

of wild meat available these men faced the real possibility of

starvation. [25]

Often their lives were in the hands of an Indian

hunter hired for the sole purpose of providing the post with meat:

"At noon the Squirrel came

in for his final payment of his winter hunt we would have all starved

had I not engaged him.” [26]

It is therefore

understandable that the men at Brandon House were extremely sensitive

to the food supply available at any inland post and their access to

them.

Indeed past experience had made the veterans

extremely conscious of just how much meat and fat, in pounds, was

needed in that severe climate in order to work during the winter

months.

To summarize, given the normal food and clothing

situation at Brandon House I found that the men knew from experience

that the company “slops” were inadequate from year to year, but the

prices for what there was available were at least tolerable.

The men also knew the

English provisions would be short and of poor quality but they also

knew that they got a share as well as the post Master.

The wild

game did fluctuate but when it was available they got good red meat

and plenty of fat for the winter.

If the trip in from Albany

was back breaking there was brandy to be had at a discount from

stores, as well as the traditional drams given to the tripmen.

It was this ability of a man

to fill his belly that made the job tolerable if not enjoyable.

It would

be the deliberate disruption of this policy by the Company committee

that set in motion the events that followed.

The Financial State

of the English joint stock Company

The Napoleonic wars had

reduced the company shareholders return to nil. Three years of unsold

fur pelts were in storage in England. Nor were the prospects for the

future favorable.

On the North American continent both American

and Canadian traders were competing with the English company for the

Indian's trade.

While the company ostensibly held a monopoly in

the fur trade, at least within the Hudson’s Bay drainage England had

neither the time nor the inclination to send sufficient troops to

enforce it. The company was, after all, a minor contributor to the

British economy at best and totally useless to a war time

administration.

By 1808 shares in the company were discounting

at 40 percent.[27] Finally in April of 1809 George H. Wollaston of the

committee presented his plan. [28]

Wollaston proposed that the

company withdraw from the interior fur trade and turn its energies to

the lumber trade along the Bay shore.

The intent of these

proposals were thereupon conveyed to Hodgson at Albany and he began

the preparations to withdraw from the interior. [29]

In the meantime, however a

family capital combine had developed in Britain which would take an

interest in the Rupertsland company.

Andrew Wedderburn a rum

merchant viewed the company's withdrawal from the Indian trade as the

loss of a market for his alcohol. In order to save that market he

combined with two in laws, Thomas Douglas a plantation owner who was

using the newly landless Highlanders to fill his plantations in

British North America and John Halkett who was a London merchant. This

partnership obtained sufficient stock in the company in order to hold

a position of influence on the committee.

The plantation owner

Douglas, along with other large land holders with large grants of

crown land in North America had been playing a major role in

stabilizing Britain's political scene during the agrarian revolution.

An officer of the Hudson's Bay Company put a positive spin on the role

of Douglas:

The unprincipled rich in the Highlands Squeeze &

Starve the poor in order to get more money. Bad however as these Rich

are we have to thank providence that the more numerous class of

Society had it not in their power to give the Law to the rest & it is

better for themselves, as well as for the nation, that they are

obliged to make a Shift for a livelihood in Canada & other parts of

America rather than dispossess by strong hand the Lawful proprietors

at home and turn masters in their turn as was the Case in miserable

France.[30]

When Douglas first considered the establishing

of a new plantation in Rupertsland he had sought and obtained an

English legal opinion as to the jurisdiction of the English company in

that region of North America.

The resulting opinion was to

have a major influence on the forthcoming attitude of the committee of

the company toward the use of legal power to control their labour

force.

Critical in the statement of that opinion was

the point that,

"...the grant of The civil and criminal

jurisdiction is valid, though it is not granted to the company but to

the Governor and Council at their respective establishments...as

judges, who are to proceed according to The laws of England.”[31]

This opinion and the

resulting action of the committee due to it emphasizes the fact that

the oppressive labour laws enacted in Britain were simultaneously

existent in Rupertsland.

In 1811 even more legal

power was placed in the hands of the company when its officers in

North America were made magistrates [32] under the Canadian

Jurisdiction Act Of 1803. [33]

Wedderburn quickly became

the determinant in the company committee of 1809 and his plan for

retrenchment superseded Wallston's plan of withdrawal.

Apologists for Thomas Douglas have maintained that Douglas was

"disinterested”, in the materialistic aspects of the relationship.

Further they have foisted that false image of a benevolent hero on

Canadian school children. This position of the apologists is

indefensible as Douglas was just one more plantation owner seeking the

success of his business.

The English company would

provide him with a ready market for the farm produce of his plantation

in Rupertsland therefore he would need both farm labourers and the

servants he had also promised to the company. In other words, Douglas

success depended upon what he could get cheaply -- what other

landlords in Scotland were throwing away - people.

Nevertheless I will concede one point to Douglas that is; that

“perhaps” his attitude toward his servants may have been tempered by

his Clapham philosophy.

In any event Wedderburn's

system would maintain the company's presence in the interior and,

therefore, their legal right to grant Douglas the land for his

plantation. Of course Douglas supported the Wedderburn system of

retrenchment and was equally responsible for its content and the

consequences that occured.

Indeed, when His lordship

was contacted on the matter of Yorston’s petition he took the side of

the committee as did his brother in-law Halkett.

So much

for his humanity and the bubble and squeek I got at school about him.

The Consequences of

Retrenchment to the Workmen in Rupertsland.

From the point of view of

the workmen at Brandon House the fundamental constituent of the

retrenchment system was the order that every post initiate an accurate

accounting of exactly every article of merchandise sold to the

officers and servants. [34] In itself the order was innocuous enough.

It was, however, coupled to a strictly adhered to a system of food

rationing.

The precise weekly ration per man was to be 10

lbs. oatmeal, 1 barley, 1 pease, 2 meat, 1 fat or 1 pint molasses.[35]

There was no indication that any allowance for the seasonal labour

requirements of an inland post were to be made.

Furthermore any extraneous circumstance, such as the strenuous nature

of certain aspects of the fur trade, were not to contravene this order

as to ration.

If a man needed, or thought he required more

food to do the job he was ordered to do he was to purchase it himself

from the company at inland prices. Further, any servant purchasing

spirits from the company was to pay full inland price the same as the

Indians did.

The best reduction on other goods or slops was

to be a maximum of one fifth or 20 percent off the "inland" retail

price of goods.

I found this interestingly stupid as the main

losses to the company were not due to a lower profit margin on the

sale of goods in the interior but the Company’s failure to find new

markets for their furs.

Furthermore it was clear to

the committee and the officers that these changes in company policy

had to cause some unrest among the servants, particularly those

working at the inland posts. However, the committee was confident they

had little to fear on that account, for Douglas had guaranteed them an

abundant oversupply of labour from his plantations on the continent.

In return for the land for the Rupertsland plantation Douglas had

agreed to provide the company with 200 men for ten years at wages of

no more than twenty ponds per annum.[36]

The Douglas Wedderburn proposal was accepted by

the committee in principal in the year 1809 and Auld the

Superintendent was ordered to make preparations for a colony on the

Red River in Rupertsland.[37] This Lowland Scot Superintendent also

began the implementation of the retrenchment policy.

Hodgson,

the Chief at Albany, was fired and his wages stopped when the company

ship reached the post.[38] The letter from the committee called it his

lack of vigor and want of activity. Auld called it misconduct and used

Hodgson’s fate as an example to threaten the other company officers

under his power.

The company wanted all of the servants in

Rupertsland placed on the same footing immediately. [39] That is to

say, they wanted them stripped of all wage supplements and reduced to

the same wage scale, using Douglas's offer as a measure.

This

action would also add to the unrest. The company therefore decided to

redistribute the labour force, particularly the Albany men in order to

break up groups of friends that might tend to form pockets of

resistance.

For example, of the Albany men at Brandon House

many of the men had served together for more than five years, some

such as Yorston and Henderson for as long as ten.

Because

of the potential unrest among the interior Albany men, the Red River

district of which Brandon House was a part was withdrawn from Albany

and placed under Auld's direct supervision.

As the Douglas Wedderburn

plan took shape it became clear that the committee was using their

English racial bigotry to justify the shift from the Orkney workmen to

Douglas's refugee Highlanders, and in the company "regulations” of the

day I found:

In consequence of the representations which have

been received from the different Factories we have determined to send

no more men from the Orkneys. A few men have been procured from the

Western Islands and Coast of Scotland where the people are of a more

spirited race than in Orkney.[40]

The labour force of a

company never deals with upper managements, be it a board of governors

or a committee of shareholders as was the case in the Hudson’s Bay

Company. It was lower management, chosen for their ability to augment

company policy, that the workmen deal with. In the case in point that

lower management consisted of Superintendent William Auld and the

officers of his jurisdiction.

Thus not only were the

workmen in the field, having to deal with the change in policy, but

also the character and methods used by the officer in charge.

In the

case of Auld, a lowland Scot who was a Uria Heap of an officer, who

had good reason to dislike, even hate, the Orkney workmen because in

1805 a combination of Orkney workmen had refused to sign on with Auld.

Thus Auld had lost a once in a lifetime opportunity to make his

fortune as a semi independent 'trader into the Athabaska district.[41]

Auld was always critical of the Orkneymen in his reports to the

committee and after 1809 he boasted to a fellow officer

"That it

is wholly owing to me that the Honorable Committee have left getting

their servants from the usual place.” [42]

As for Auld's relationship

to the servants under him he constantly attempted to force upon them

the same servility he himself portrayed towards the committee.[43]

Among the new regulations,

the committee decided that servants were no longer to have access to

the English provisions at all.

Again the rationale for

their penurious attitude was determined by their racial and class

prejudices:

We are of opinion That the Rations of meat

hitherto allowed have been extravagant, especially when in

consideration that so great a proportion of our men are natives of a

country where Butcher’s meat forms scarcely any part of the ordinary

diet of the labouring people.[44]

It is doubtful that under

any circumstances the transition to the new system would have been

uneventful. But the problems with labour were compounded by the

further blunders of the upper and lower management of the English

company as they forced through the changes.

First,

their rejection of the Orkney workmen by the committee had been

woefully premature. Douglas's obligation to provide a cheap over

supply of labour would not begin until 1812. As it turned out the

company's own interim recruitment in the Highlands had been a failure.

Finding that they were still in need of the Orkneymen upper management

decided to conceal the tenor of the regulations by refusing to allow

even the officers in the field to read an official copy of them:

from a total want of success

in procuring men in the Highlands & Western Islands of Scotland there

are parts in the regulations which reflect on the character of the

Orkney Servants so pointedly that in our present state of entire

dependence on them it would be the extremity of folly to irritate them

so unnecessarily as would be the case on their becoming acquainted

[with the contents]...

We therefore earnestly recommend to you to

conceal all these regulations from your officers so that no possible

chance may allow of their contents getting among the lower

Servants....

...at the same time we by no means desire to

restrain you from complying with the regulations only enforcing them

from you own private Authority which is amply sufficient.[45]

In the past the servants of

the company had been ordered to obey the official "regulations” of the

committee as they were posted at the Posts.

The work which the servant

had agreed to do was also set down in those regulations. It was the

responsibility of the officers to decide where and when but not what

the men were to do.

This was the image held by the servants of the

agreement under which they worked. It was an ideal, to be sure, as the

men were often called upon to do employment outside the realm of their

agreement with the company. However, when the men did feel put upon by

a company officer they could demand to see his authority in the

writing of the regulations.

This time it was Auld's

intention to enforce the retrenchment system based solely upon his

personal authority. Then through due process he expected to be able to

transfer that personal authority to the officers within the Red River

district.

This, however, gave them far more power than

they had ever known before. Under this regime the servants were

expected to accept and conform to the new regulations solely on the

word of lower and lower levels of management.

These then were the factors

that had originally shaped the conditions of the workmen at Brandon

House and the factors added by company policy changes that introduced

the “new order” in their world in their time.

The Key Participants

in the Brandon House Labour Dispute

There were a number of

individuals who were actively involved in the events at Brandon House.

The key figures on the company side were William Auld, Superintendent

of the company in America, Alexander Kennedy Master at Swan River and

Brandon House, and Hugh Heney officer in charge of Red River. These

were the middle and lower management personnel in the dispute

One of the chief organizers

of the labour combination was George Henderson a fourteen year veteran

in the company service. He was a common labourer and could not read or

write. Twelve of those years had been spent at Brandon House.

The second leader of the

combination was John Cumming. He was a relatively new man, only in his

second three year contract.

Two other individuals took

prominent positions in the events. The first was Archibald Mason. I

believe Mason was origionally sent over as an agricultural advance man

for the proposed colony. At first he appeared in the role of an

officer in the company but at the time of the dispute he took the side

of the combination. Later he fled to Canada with the help of the

Nor’westers.

The second individual was William Yorston, a

literate Orkney labourer who had come up through the ranks. He became

the man caught in the middle. At the beginning of the events at

Brandon House he was Indian trader and second in command. In the

service since 1796 he had learned the trade in the field and the

Indians "knew" him at Brandon House.

In 1808 09 he had also built

the trading post at Manitoba House and had run it.

It was

because of his personal ability that Brandon House did not loose the

trade to the Canadian traders during the Post Master's annual trip to

the bay during the summer.

In spite of his service and

the promises of his immediate superiors his salary had remained at 18

pounds per annum. Furthermore the company was fifty seven pounds in

arrears in the money owed to him.

Brandon House May

1810

I would say that the events at Brandon House

began in May of 1810. It was then that Yorston requested permission

from the Master at Brandon to go down to Albany and petition for the

f35 a year salary he had been promised.

But McKay the Master was

deathly ill with consumption. He asked Yorston to remain inland for

the sake of the post and Yorston agreed to do so. On the 5 of July

McKay died and Yorston took charge of the post.

Most of the men including

Yorston himself appear to have expected that he would retain the

position of Master until the order for the proposed withdrawal to the

bayside came inland.

Brandon House was a difficult post to run. This

was primarily due to the competition of the Canadian Northwesters.

However, Yorston had built a good reputation among the Indians and as

Indian trader he had held the trade at the post together.

Further,

the men trusted him, particularly the veterans who had worked under

him on trading expeditions onto the plains and the establishment of

Manitoba House. Therefore it was a surprise to all of them when Thomas

Norn was sent inland with orders to take command of the post. However

his tenure by his own wishes was short lived

Mr. Norn however had been

only Eight days in office when he owned to the petitioner, [Yorston]

that from his ignorance of the trade in that district, and of the

humour of the traders, whom, be saw daily leaving the place, he was

quite unfit for the management, and begged that the Petitioner (to

prevent the total ruin of the Company’s Interests in that quarter)

would again take command.[46]

Once more Yorston took

command. But an air of uncertainty grew as the summer passed and no

word on the future, in the expected form of an order to move came in

from Albany.

If they were to close down the establishment and

remove to Albany they would have to do so soon or risk a very cold run

down the Albany River to the Bay side. They might even be caught by

the freeze up and be forced to walk out.

Then on October 23

"to

[their) great surprise" Humphrey Favell arrived at the post with their

letters from home and a letter from Hugh Heney the officer in charge

of Red River. [47]

The letter informed the post that the company

had changed its mind and that it intended to maintain the Red River

district and the establishment at Brandon House.

Yorston's surprise increased when Heney did not include the copy of

the regulations for the ensuing season in the packet.

This

unusual occurrence was also noted by the men at the post, especially

when Favell informed them of the rumors of he had picked up at Red

River concerning the fantastic prices they would have to pay for

slops.

In his letter Heney ordered that Brandon House

send four carts, two horses with riding saddles and two pack horses,

to the forks of the Assinaboine and Red rivers to meet Superintendent

Auld. In the instructions Heney ordered: "You'll give the men a

fortnights provisions to here, [the forks] in wait of our

Superintendent." [48]

Yorston did as he was instructed and added 175

lbs. piece meat to the provisions. On 26 October he sent Thomas

Measson, Andrew Barkie and John Wishart with Humphrey Favell with the

outfit, to the forks.

The men arrived at the forks on 30 October but

found that Auld had not yet arrived. Heney then decided that he wanted

to go to Brandon House and ordered Measson and the Brandon House

servants to remain at the forks until Auld appeared.

Measson

objected to the indefinite period of time involved in the order. They

did not have their winter clothing with them nor more than the

provisions Heney had ordered.

Heney became furious at the

mere questioning of the order. He ordered Measson to remain at the

forks as it was his duty to obey and if he did not he would no longer

be allowed to serve the company.[49]

Measson was one of the ten

year veterans. He understood clearly the implications of remaining at

the forks of the Red River during November without food, clothing or

proper shelter and he continued to refuse.

Heney then tried to take

control of the horses to force the men to remain at the forks. Measson

refused to hand the stock over to the officer. Heney armed himself in

an attempt to browbeat the men into submission.

Measson

told the armed officer be had brought the horses from Brandon House

and he would take them back there again. The Brandon House servants

then left to go home.

Heney had ordered Brandon House to send two

weeks provisions with the carts. It had taken the carts four days to

reach the forks empty. Presumably it would take at least five days to

return. That left a maximum of five days at the forks. We can presume

that the meeting at the forks took up at least one day, leaving

Measson and the men with only four days provisions.

Heney

had demanded they remain at the forks indefinitely for Auld, who may

have been delayed or may have changed his mind. They could not know.

However when Auld reported

this incident to the committee he managed to turn Heney’s gross

stupidity into a consciously mutinous act on Yorston's part.[50]

Auld claimed that Yorston

bad deliberately short rationed the outfit in order to interfere with

Auld's inspection trip. This Auld would state proved that the

Orkneyman Yorston had been the first rebel and the instigator of the

later mutiny.

With, the return of Measson and his story the

anxiety of the men at Brandon House intensified. All they knew of what

was going on was what they had heard from Favell and the rest of

Heney’s men.

It was through this chain of rumor that they

learned that Heney was telling the Indians in the Red River district

not to hunt furs but to concentrate on bringing in provisions.[51]

This bizarre situation continued, for under Auld's orders Heney had no

copy of the regulations to show Norn, Yorston or anyone else at

Brandon House. Heney did, however, attempt to implement and enforce

the new order regulations using his personal authority.

The reaction of the servants

to this was understandably resistive and it was immediate. Even the

even tempered Yorston was furious that Heney had not done him the

courtesy of showing him the regulations which gave him the authority

to implement the changes.

Later Yorston would inform

Kennedy that,

“he [Yorston) considered no man in this Country

to be his master, the Hudson’s Bay Company only were his masters, and

to them be would be answerable for his conduct.” [52]

There was no doubt in my

mind that Yorston was, throughout his entire service with the company,

loyal to its interests. But that loyalty was misplaced for the company

had chosen to abandon any right to personal fealty on the part of its

servants for the English legal power they had vested in their

Rupertsland officers.

When Heney undertook to tell the Brandon men the

regulations that pertained to the costs to servants the men went on

strike:

Nov. 5 Gave orders for the next day Employment

to the men. They would not work till such times that the Price of

Slops would be reduced to the Old Standard was their answer.[53]

Heney’s reaction was to

threaten the men’s lives with expulsion from the safety of the company

fort

Nov. 6 Wrote down to the men that whoever

refused his duty I could not supply them with victuals they must take

to the plains and shift for themselves till the Spring.[54]

This was an unmitigated

bluff for Heney had no means of enforcing the threat. The servants

knew this but the very idea that Heney might consider starving them

into submission made the men hate him even more.

However,

the barrack room lawyers in the men's quarters knew that a combination

was illegal. As the men had apparently managed to get their slops for

the winter bought before Heney had arrived they sent him a counter

proposal:

They returned an answer that they did not refuse

their duty and they wished that the Price of Slops as Mr. Kennedy's

man 'had informed them and wished I could assure them that what they

had bought to the day I arrived should be at the old Price of 1809

which I gave them without hesitation,[55]

Thus the men set aside the

main problem of the price of slops for that winter at least. But the

problem of provisions remained.

Brandon House had, for the

most part, a good supply of meat when the buffalo herds were nearby.

For example, in October 1809 the Assinaboine Indians had brought in

1,000 lbs. of meat and 2,400 lbs. of fat. [56]

Under the old regime the men

had favourable access to that supply. But now they found Heney was

weighing the fat on hand in order to insure it was only distributed by

ration.

Thus Heney’s relationship with the servants of

the post continued to deteriorate. He took to wearing his pistols in

his belt, loaded and primed. He also began to abuse the men verbally,

calling them Orkney dogs.

Heney was a Canadian.

The Work Slowdown

On 8 December Heney left for

Pembina Post but returned on 17 January. With him he brought Archibald

Mason

Mason would play an interesting role in what was

to transpire. As I already noted he was ostensibly sent to the Red

River to survey the potential for agriculture in the region. Aboard

ship on the trip out Auld had treated him as an company officer.[57]

It was interesting to note that when the agreement between the

plantation owner and the company was finally written into a legal

document in June 1811 Mason's name appears among the officers

considered to be servants of both the fur trade operation and the

plantation.[58]

When they reached Brandon House Heney’s initial

relationship with Mason appeared to be excellent. In fact Heney often

relinquished the head of the table to him.[59] However, Mason at one

time called the company committee Raskals and Jack Asses. [60]

While Auld had always been

suspicious that the Canadian traders had been “concerned" with the

mutiny as he put it, he had no proof [61]. On the other hand Mason,

when he did escape the attempts of the English company to capture him,

he did so with the help of the Norwesters. Therefore I concluded that

that Mason may well have been an agent provocateur for the Norwesters

or at the very least a spy for them.

On Heney's return to Brandon

House I discovered that the journal entries indicated that the men had

instituted what amounted to a work slowdown. He then attempted to get

the men to put their hand to an agreement in principle, to his

authority:

"Sent an order down to the men who ever were

willing to Remain any longer in this Department to sign their names.

None consented," [62]

Considering that it was the company's intent to

reassign the men anyway, this order was a ploy on Heney’s part to

institute a pseudo legally binding contract on the men to obey his

authority.

Nevertheless not all the men at the post were in

agreement with the combination although those who did not agree did

defer to the will of the other men resident in the servant's quarters.

Barkie, for example, claimed neutrality. Although he did not support

the combination he would refuse to comment under Auld's inquiry,

stating he had heard nothing.

Isbister and Plowman went

over to the company as soon as they were away from the combination.

Thomas Favell remained terrified throughout the period, first of Heney,

then of the combination and finally of Auld.

The Mutiny

On 24 February Heney decided

to return to Pembina. He wrote a letter officially placing Norn, not

Yorston, in charge in his absence. He further aggravated the men by

stating in the same letter: "Should the men ask to buy any Goods

Brandy, Leather or any other articles whatever, you cannot sell any is

to be your answer.[63]

Later on that evening Heney and Mason were

engaged in a drinking bout. When he had become intoxicated Heney made

a number of inappropriate remarks:

(Heney) has cast some

curious capers of his own, with regards to Prices of Goods etc. etc.

finding himself on his last legs, in Sending of his wedded wife and

taking master McKays Eldest Daughter, which did not happen, in order

to get his hands on the Deceasts (sic) money finding himself short of

Cash in gowing (sic) to England...[64]

At some point in the evening

Mason left the scene in an inebriated state and made his way to the

Cooper's Room where he went to bed.

Soon after Heney armed

himself with two pistols and set out to look for Mason. He intended to

force Mason to Fight a duel with him. At that point the servants took

the matter into their own hands.

The men on the Instant

disarmed him and Told him it was not Customary for masters to go

amongst their men armed and also said they would no longer be under

his subjection or orders and when ever the Honble Company thinks

proper to call them home concerning this Behavior they are ready to

Plead their cause.[65]

Even Isbister, the company serf was shocked at

Heney’s reaction to this interference. Isbister reported that Heney

"almost broke down the room about himself with madness saying he would

bring us to England and do for us all.” [66]

However Isbister also

revealed that the combination had planned to force the removal of

Heney from command even before this incident took place. [67]

After

they had disarmed Heney the combination asked Mason to take charge as

they assumed he was an officer in the company however Mason declined.

Yorston then wrote in the Brandon House journal: "Finding the House in

want of a master I undertook it and managed the Business to the best

of my knowledge . “[68]

Nor could I find any evidence that the

circumstances were anything other than what Yorston reported.

He

definitely shared the men's dislike of Heney and he no doubt felt he

had a justifiable right to the position of Master for all his service

to the company. But he had nothing to do with the disarming of Heney,

and Heney had departed that night deserting the post.

If

Yorston failed in his role as post Master it was because of his

interest in the fur trade. It appears he did not appreciate Brandon

House’s new role as butcher shop to the plantation owner.

The Orkney workmen had used

the combination before in attempts to achieve their interests in

Rupertsland. At times they had been successful and at other times they

had failed.

For example in August 1777, a servant William

Taylor had refused to go inland for less than fifteen pounds per

annum. However Taylor made the mistake of mentioning the combination

before the rest of the men reached the bayside to support him.

The

company officer Martin put him on one pound of bread a day and

threatened to fine him his past wages which were still in the

company's hands, on the pretense of disobedience if he did not rehire

immediately for six pounds. Taylor submitted. [69]

It was generally only the

boatmen, who moved the company freight, who had fairly good results

from the combinations.[70] But that was because they could use the

threat of delay in the inward movement of trade goods to pry

concessions out of the company officers. But with the guarantee of an

over abundant supply of obedient cheap labour by Douglas [7l] even

their weapon of solidarity was severely reduced.

However, in a case similar

to the situation at Brandon House a combination of 15 workers had

successfully forced the removal of the tyrannical Lowlander, Robert

Longmoar, by refusing to work under him. [72]

When

Auld heard of the events at Brandon House he determined, at any cost,

to break the combination which he called a mutiny.

Breaking the

Combination

With the coming of spring and just before the

boats were about to leave Brandon House for the bayside the company

officer Alexander Kennedy arrived at the post.

He had

orders from Auld to bring them all down to York Factory not Albany.

However the servants at the post informed him that they all intended

to go down to Albany.

The men's argument remained what it had always

been that they had not yet seen the new regulations in writing so they

would abide by the old.

Yorston for his part asked

Kennedy to show him the new regulations. Kennedy exploded with his

characteristic vociferousness:

I told him if I had fifty

papers, he should not be able to boast of having compell’d me to

produce them as he had done with Mr. Heney & that if he did not chose

to take my word he might do as he pleased but that he should stand to

the consequence.[73]

This was another example of the absolute

obedience now expected of the company servants.

It is

interesting to note that the officer next attempted to weld the old

“duty to the company" to his "word of authority" by use of coercion:

...if He would return to a

sense of his duty, and go out to York with one or remain Inland as

might be required. I should interest myself in his favour and do all I

could for him. If on the contrary I was obliged to go to York & join

Mr. Heney) in his accusations against him he might depend on being a

ruined man. [74]

These creatures of the company who had survived

the retrenchment purge were desperate in playing their roles as

officers and gentlemen in the service of the Honorable Company.

Much had

been taken from a military paradigm to fabricate this model. Part of

their image was couched in the myth that a gentleman's word was 'his

bond and therefore the lower ranks should obey that word without

question.

The servants on the other hand, had their own

ideal, even myths, that their relationship with the company was

contractual. What they had put their hand to was not the equivalent of

the King's shilling.

Auld would also offer his good word to Yorston

in his letter of July 1811. [75] Auld offered to stand for Yorston if

Yorston would betray Mason. But Yorston had no reason to trust the

gentlemen officers of the company. Four others had given their word to

him that his good service to the company would receive due reward and

it had not.

Nor would his last experience with the company

have changed his opinion as he was still trying in 1817 to get back

his personal belongings that the company officers had seized in 1811

from The Honorable Committee.[76]

Returning to the events as

they transpired Yorston at first decided to go down to the ship at

York and face Auld. Then he changed his mind. Probably on second

thought Kennedy's reaction made Yorston realize that he was in far

more trouble than he had ever appreciated before.

Kennedy had made clear to

him that the company that he had served so faithfully thought he had

led the revolt against Heney.

The key to Kennedy's

argument had been a lack of obedience. When Yorston had explained that

the reason He had moved the location of the post was a lack of wood

and pointed out that the move had been made in good order, Kennedy

berated him for doing it without permission.

The officer had then told

Yorston, “that a thing done contrary to orders was seen to be wrong be

it never so right.” [77]

Yorston apparently then

decided on the basis of his experience with Kennedy for he had not yet

met with Auld nor apparently knew Auld's opinions on the matter at

that time was to hold tight at Brandon House.

Mason on the other hand had

already disappeared before Kennedy's arrival. Mason had learned, one

expects, through the Norwester’s “moccasin telegraph" that Kennedy was

bringing irons in with him. On his arrival Kennedy did make it clear

that he had intended to send Mason to Auld in chains.

Some of the servants, who

had participated in the combination, decided to go down to the bayside

with the intention of just going home. Others attempted one last time

to come to some reasonable terms with, the company:

I (Kennedy) had asked every

man separately whether they would consent to go down to York according

to the orders of the Honble Committee or were still determined on

going to Albany contrary to their orders they all said to a man they

were willing to go to York provided I would promise Them the same

allowance they had formerly at Albany & That they should return again

to Red River [78]

It was a futile gesture for although the

officers had been given full authority to enforce absolute obedience

to the regulations they had lost all their former personal initiative

in dealing with the men.

It had become a standoff.

Kennedy then tried to win the men over by getting them drunk. When

this failed he took the crew he could get and started for York

Factory.

The rest of the servants who chose to leave

Brandon House started for Albany House.

Once the men in the

combination left Brandon House it was effectively broken.

By then

the servants had made personal choices that broke them up into three

separate groups; those that remained at Brandon House and those who

went down to the bay side either to York Factory or to Albany.

At the

bayside they became an isolated minority under the guns of armed

officers.

York Factory Punishing the Workmen

The men who went down to

York were questioned by Auld, apparently at oxford House where he had

been awaiting them. He was afraid that they might get support from the

ships crews or other workmen.

Under the English labour

statute they could be forced to give evidence against themselves. Auld

summed up the situation in his report to The committee in t1he

following manner:

Those 5 men from Brandon House were told to

proceed to other places to spend the remaining part of their Contracts

at first they all refused but on finding us resolute in preventing

them returning to Red River three of them acquised but two would

rather be sent down to go home accordingly they are brought down to

Y.F. but not to be allowed to go home they shall continue here until

your pleasure is known next year we shall dispose of them to the best

advantage I Hope also to have all their associates secured & waiting

the arrival of the ship,[79]

Albany Punishing the

Workmen

The same type of enforcement awaited those who

had chosen Albany.

Their personal property, sent to York Factory,

was seized. They were then refused "any supplies unless the bare

necessities of life to enable them to perform their contracts.”[80]

The men were in effect put

on half rations and had only the clothes they stood in.

On 23 July the Albany Factor

under English legal authority brought the leaders of the combination

to trial.

Cumming was already in irons and kept in

solitary confinement for being insolent to the officers of the

company.

They were tried by a tribunal. The officers were

Thomas Vincent, William Thomas and Jacob Corrigal. [81]

Cumming

and Henderson were found guilty of "Mutinous Conduct." They were left

on half rations until they were sent home wageless to Scotland.

Auld had promised the

company to have all the so called mutineers in custody upon the

arrival of the ship the following year. That included Yorston.

The man

sent to Brandon House to ensure that Yorston came in the following

year was Kennedy.

Yorston and Kennedy The Winter of 1811

12

Kennedy arrived at Brandon House on 20 September

1811, to take charge. He immediately began to sabotage Yorston's trade

Yorston had never allowed

the company's business to deteriorate during the entire episode. The

fact that he had remained in position over the summer for so many

years was what had made the post the success it was.

What

occurred with the arrival of Kennedy is given here from Yorston's

point of view:

Shortly after his arrival, he set out to

purchase goods from the Indians, and the Petitioner who was creditor

[Indian trader for the company] to several Dealers [Indian Captains]

in the country, through which He was to travel requested that he would

take to trouble of Collecting the Arrears due to him. Kennedy however

instead of doing this told the Petitioners Debtors that they might pay

their arrears at some other time and on this return falsely informed

the petitioner that they had refused Payment. The first time that they

came to Brandon House, the Petitioner reproached them for breach of

faith and then the deceit which Kennedy had practiced upon both

parties, was completely unraveled. The Indians, being quite indignant

at this conduct, directly accused 'him of falsehood, declared that

they would have no more dealing with Him and went over to the

Canadians.[82]

The next major confrontation between Yorston and

Kennedy occurred in January 1812 when Kennedy ordered Yorston to lead

an expedition to the dangerous Missouri country to compete with the

Americans.

Yorston had not been engaged to perform such

dangerous service and his wage certainly did not indicate it. Further

as he had watched the Missouri trade for some years he knew what the

Indians would trade for. What Kennedy intended to send was unfit for

that trade. [83]

Finally Yorston knew that the company rate of

exchange would not compete with what the Americans were offering. He

told Kennedy all this. Kennedy then lost his temper and struck Yorston.

What occurred is in the record in Kennedy's own words. The reader must

recall that as far as the company officers were concerned Yorston had

already been declared guilty of mutiny and was therefore beyond the

pale of law:

I gave him a slap or two in the face which he

endeavoured to return but I avoided or parried off. After the fist

scuffle I insisted on his positively telling me whether he was

determined on going to the missouri or not, that I might take my

measures in case he refused his duty He told me I had prevented him

from going by disabling him. I told him that not a, answer and

insisted on his directly answering me the question I asked or I would

throw him out doors he said he would not give me a more satisfactory

answer nor would he go out doors till he pleased himself. Upon which I

run for the next room and found a pair of tongs which I took up and

threatened him two or three times to walk out and go into the mens

house Where he should remain on half allowance till spring & If He did

not I would break his head, he set as obstinate as a mule upon which I

fetched him a crack on the arm with the tongs.[84]

Upon which Yorston rose from

his place and disarmed Kennedy. Then he proceeded to give the officer

a sound thrashing. When it was clear to Kennedy that he was to be

given what he gave, he called upon the servants to remove Yorston. The

men refused to interfere. Kennedy turned and ran.

Kennedy

then armed himself and tried to kill Yorston. Yorston fled the

Hudson’s Bay Company Post and sought sanctuary with the Norwesters.

Next Kennedy went to the

Canadian post and offered 100 guineas for Yorston in chains.

To put

this ridiculous bounty into perspective one must recall that Yorston's

salary was less than 20 pounds per year.

The Canadians refused. But

their comment to Kennedy was prophetically. They told Kennedy that if

he really wanted Yorston all he had to do was wait until he got him to

the bayside factory.

Why, I asked myself, did Yorston not go over to

the Canadians? There is no doubt they would have taken him, not just

to bother the English, but to increase their trade, for Yorston's

Indians would have followed him.

But the company owed Yorston

the equivalent of forty seven pounds in back wages and He would loose

all of that plus his last two year's salary if he left.

Further, Yorston had been comfortably

established at Brandon House before the chaos began. His property

included small but expensive luxuries such, as silver tongs, six

silver tea spoons, a coffee mill, six crystal glasses, and a small but

substantial library.

Finally, Yorston still imagined that his

problems lay specifically with Heney, Kennedy and Auld. He still could

not believe that the Honorable company did not care to hear his side

of the story. He still felt that once they had heard the truth, he

would be vindicated and the post at Brandon House or its equivalent

would be put in his charge. It was a forlorn and most foolish hope.

And so Yorston conceded once

more to Kennedy and agreed to make the trip to the Missouri country.

As he had predicted it was a disaster for the goods and prices could

not compete with the American trade.

When he returned to Brandon

House Yorston found the trade at the house was in an even worse state,

for the general dislike of Kennedy had spread among the Indians.

Kennedy asked Yorston to

take over the trade once more for the sake of the company and of

course Yorston did.

Nor was Kennedy's relationship with the workmen

at the post any better. He had enforced the company ration throughout

the winter months. With the coming of spring the men’s resentment

reached a peak and they went on strike:

April 16 the people sent to

me that they wanted fat to eat with their meat which I refused, having

served them out 56 lbs only eight days ago they again sent me word

they would not go to work unless they were served out fat with their

meat.[85]

Kennedy told them that the ration they had

received was in the regulations. The men asked to see the regulations.

Kennedy refused to do so and told them if they wanted more food he

would sell it to them.

The Punishment of Yorston

With the coming of spring

Yorston gave up and decided to leave the company. When he informed

Kennedy of his intention the company officer ordered Yorston’s

personal effects seized [86] and Yorston was forced to leave without

them.

When Yorston reached York Factory Auld

questioned Him and immediately lied to Yorston by telling him that he

had not seen Yorston’s Brandon House journals. Later it came to light

that Auld had read them all.

Two days later Yorston and

The other men from Brandon House were ordered to appear once more.

Auld informed Yorston that he and the other officers of the company

intended to make an example of him.

Neither Yorston nor the

others were allowed to answer to the charges or question their

accusers.

On 12 July The Governor sent his second in

command James Tait with an order that the Petitioner, Yorston, should

proceed for six miles into the woods and remain there for fifteen

days. [87]

Yorston was given a ration of two gills of

unsifted oatmeal and one lb. of rotten bacon per day. He was without

arms or shelter.

Yorston contracted what the medical profession

of the day called distemper. But Auld, himself ostensively a

physician, refused to allow him medical attention.

It was

the unanimous decision of the officers of the English company to send

Yorston to Scotland in chains. [88]

However, as it was the

intent of the punishment to terrorize the workmen in Rupertsland Auld

allowed Yorston to leave unchained.

It may have crossed the

reader's mind that the officers of the company had overextended their

authority by these actions. On the contrary, the English committee

applauded and encouraged them to use the full extent of their

authority to break the combinations:

We read with very great

regret the account of the mutinous conduct of Archibald Mason, William

Yorston & others at Brandon House & we cannot too forcibly impress

upon your minds the importance of preserving the strictest discipline

amongst the men & enforcing the most prompt & ready obedience to the

orders of their respective chiefs [89],

The committee confirmed the

punishment imposed on John Cumming and George Henderson. They

confiscated all of Archibald Mason's wages and gave Auld a carte

blanche to have punished Yorston with, “such punishment as may be

thought commensurate to the enormity of the offense.” [90]

When Yorston sought the

wages he was owed they informed him:

I am directed by the

Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company to inform you that

from the official documents from Hudson’s Bay the conduct of the said

Yorston instead of being that of a good Servant worthy of reward he

appears to have been most unruly and mutinous and rather deserving of

Punishment thanof any remuneration.[91]

In 1814 a further attempt

faired no better. But it appears that Yorston may have received some

money in 1815.

However, in 1817 Yorston still had not yet

managed to retrieve 'his personal property from the company, [92]

My Conclusions

The struggle for descent

working conditions and a fair return for service that has been

outlined here was the same struggle that was going on in the

collieries and mills throughout the British Isles. If there was a

difference it was in the absolute success the English Hudson’s Bay

Company had in suppressing the aspirations of the working class. This

was achieved by the brutalization of the workmen.

In

desperation one of the Brandon House men begged his Masters for

forgiveness and pledged his entire life to the service of the company

in the same subservient way as the wife had called upon her husband to

die.

However, it is a letter from one officer of the

company to another that best portrays the success of the campaign:

I am only able to send you

one man at this time he was engaged by Lord Selkirk's Agent at

25(pounds) per annum & is now on no terms at all. He is one of a party

that was off Duty part of last winter but having been scowered into

obedience by a rejinem (sic) of Bacon & oatmeal & not a little

chastised by the musketoes (sic) for he led a sylvan life he soon saw

his error & is now willing to serve his time out at such, wages as

maybe here after settled by the committee & it is certain he will not

be allowed more than 20(pounds) pe(r) year.[93]

FOOTNOTES

1. E.E. Rich, Cumberland

House Journals and Inland Journal 1775-82, 2nd Series 1779-82. (The

Hudson's Bay Record Society London 1952. xxxvii.

2. Eric Linklater, Orkney

and Shetland. (Robert Hale, London 1971), 83.

3. E.E. Rich, Cumberland,

2nd Series, xxxix.

4. Petition for William Yorston to the Directors

of the Hudson's Bay Company, Kirkwall, 1814, A/10/1 (Hudson's Bay

Company Archives, Winnipeg).

5. Thomas Johnston, The

History of the Working Classes in Scotland. (Forward Publishing Co.

Ltd. Glascow n.d.), 47.

6. G.D.H. Cole and Raymond Postgate, The Common

People 1746-1946. (Methuen & Co. Ltd. London 1963), 7.

7. Ibid., 121.

8. Johnston, Working Classes

in Scotland, 197.

9. John Prebble, The Highland Clearances. (Penquin

Books, Harmondsworth 1969), 61.

10. W. Cunningham, The

Growth of English Industry and Commerce, Vol. 3. (University Press,

Cambridge 1912), 715.

11. Charlotte M. Waters, An Economic History of

England 1066-1874. (Oxford University Press, London 1925), 317.

12. Johnston, Working

Classes in Scotland, 265.

13. Frederic Morton Eden,

The State of the Poor. (Benjamin Bloom, New York 1971), 111.

14. Rich, Cumberland, 2nd

Series, xlviii.

15. Johnston, Working Classes in Scotland, 61.

16. Rich, Cumberland, 2nd

Series, xl.

17. William Auld, Churchill, August 1810,

B/42/6/53, (HBCA).

18. Brandon House 1803-04, B/22/a/11, (HBCA).

19. Brandon House 1799-1800,

B/22/a/7, (HBCA).

20. Brandon House 1801-02, July 6, B/22/a/9,

(HBCA).

21. Brandon House 1810-11, June 9, B/22/a/18a,

(HBCA).

22. Brandon House 1804-05, B/22/a/12, (HBCA).

23. Brandon House 1805-06,

August 8, B/22/a/13, (HBCA).

24. Rich, Cumberland 2nd

Series, xlix.

25. Brandon House 1803-04, November 20,

B/22/a/11, (HBCA).

26. Brandon House 1799-1800, March 22, B/22/a/7,

(HBCA).

27. E.E. Rich, The Fur Trade and the North West

to 1857, (McClelland & Stewart, Toronto 1967), 205.

28. E.E.

Rich, Hudson's Bay Company 1670-1870, Vol. II, (McClelland & Stewart,

Toronto 1960), 271.

29. William Yorston & Thomas Norn, Brandon

House, Nov. 1810, B/159/c/1 and Brandon House 1810-11, October 23,

B/22/a/18a (HBCA).

30. D. Cameron, Lake of the Island, March 22,

1804, B/239/b/72, (HBCA).

31. Beckles Willson, The

Great Company. (Copp Clark Co. Ltd., Toronto 1899), 374.

32. Arthur S. Morton, A

History of the Canadian West to 1870-71. (University of Toronto Press,

Toronto 1973), 539.

33. Rich, Hudson's Bay Company, Vol. II, 274.

34. William Auld, Churchill,

August 1810, B/42/b/53, (HBCA).

35. Instructions for

Conducting Trade, Hudson's Bay House, 31 May 1810, B/42/b/54, (HBCA).

36. William, The Great

Company, 378.

37. Rich, Hudson's Bay Company, Vol. II, 300.

38. Hudson's Bay House, 31

May 1810, A/6/18, (HBCA).

39. Instructions for

Conducting the Trade, Hudson's Bay House, 31 May 1810, B/42/b/54,

(HBCA).

40. Instructions for Conducting the Trade,

Hudson's Bay House 31 May 1810, B/42/b/54, (HBCA).

41. Rich, Hudson's Bay

Company Volume II, 284.

42. Williams Auld, Churchill, 3 March 1811,

B/42/b/54, (HBCA).

43. William Auld, Churchill, August 1811,

A/11/16, (HBCA).

44. Instructions for Conducting the Trade,

Hudson's Bay House, 31 May 1810, B/42/b/54, (HBCA).

45. Orders Received by Auld

1810, B/42/b/54, (HBCA).

46. The Petition of William

Yorston, A/10/1, (HBCA).

47. Brandon House 1810-11,

B/22/a/18a, (HBCA).

48. Ibid.

49. Deposition: Thomas

Mason, (Measson), B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

50. Williams Auld, Churchill

August 1811, A/11/16, (HBCA).

51. Deposition: John

Corrigal, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

52. Report of Alex Kennedy

to Auld 1811, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

53. Brandon House 1810-11,

B/22/a/18a, (HBCA).

54. Ibid.

55. Brandon House 1810-11,

November 6, B/22/a/18a, (HBCA).

56. Brandon House 1809-10,

October 14, B/22/a/17, (HBCA).

57. William Auld, Churchill,

August 1811, A/11/16, (HBCA).

58. Chester Martin, Lord

Selkirk's Work in Canada (Oxford University Press, Toronto 1916), 205.

59. Deposition: George

Henderson, 10 June 1813, A/10/1, (HBCA).

60. Deposition: William

Plowman, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

61. William Auld, Churchill,

August 1811, A/11/16, (HBCA).

62. Brandon House 1810-11,

February 22, B/22/a/18a, (HBCA).

63. Brandon House 1810-11,

B/22/a/18a, (HBCA).

64. Archibald Mason and William Yorston, Brandon

House, 26 February 1811, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

65. Notation signed William

Yorston, Monday 25 [February] 1811, Brandon House 1810-11, B/22/a/18a,

(HBCA).

66. John Isbister, February 24 and 26, 1811,

B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

67. Ibid.

68. Notation signed William

Yorston, Monday 25 [February] 1811, Brandon House 1810-11, B/22/a/18a,

(HBCA).

69. E.E. Rich, Cumberland House Journals and

Inland Journals 1775-82 First Series.(Hudson's Bay Record Society,

London 1951), 142n.

70. Harold Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada.

(University of Toronto Press, Toronto 1856), 159.

71. Hudson's Bay House to

Auld, 31 May 1811, A/6/18, (HBCA).

72. Rich, Cumberland 2nd

Series, 183.

73. Alex Kennedy Report to Auld 1811, B/22/Z/1,

(HBCA).

74. Ibid.

75. William Auld Oxford

House July 1811, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

76. Hudson Bay House to

William Yorston 29 November 1817, A/5/5, (HBCA).

77. Alex Kennedy Report to

Auld 1811, B/22/Z/1, (HBCA).

78. Ibid.

79. William Auld, Churchill,

August 1811, A/11/16, (HBCA).

80. William Auld, Churchill,

August 1811, A/11/16, (HBCA).

81. Albany House 1810-11,

B/3/a/114, (HBCA).

82. Petition of William Yorston, A/10/1, (HBCA).

83. Ibid.

84. Brandon House 1811-12,

B/22/a/18b, (HBCA).

85. Brandon House 1811-12, B/22/a/18b, (HBCA).

86. Petition: William

Yorston, A/10/1, (HBCA).

87. Ibid.

88. William Auld, York

Factory, January 1813, B/239/b, (HBCA).

89. Hudson Bay House, May

30, 1812, A/6/18, (HBCA).

90. Ibid.

91. Hudson Bay House,

January 20, 1813, A/10/1, (HBCA).

92. Hudson Bay House,

November 29, 1817, A/5/5, (HBCA).

93. Cook to Swain York

Factory, 20 July 1812, B/239/b/84, (HBCA).

94. E.H. Oliver (ed.), The

Canadian North-West Its Early Development and Legislative Records

Volume II, (Government Printing Bureau Ottawa 1915), 1287.