The golden lilies in danger—"To arrest

Radisson"—The land called "Unknown"—A chain of claim—Imaginary

pretensions—Chevalier de Troyes—The brave Lemoynes—Hudson Bay

forts captured —A litigious governor—Laugh at treaties—The glory

of France— Enormous claims—Consequential damages.

The two great nations which were seeking

supremacy in North America came into collision all too soon on the

shores of Hudson Bay. Along the shore of the Atlantic, England

claimed New England and much of the coast to the southward. France

was equally bent on holding New France and Acadia. Now that

England had begun to occupy Hudson Bay, France was alarmed, for

the enemy would be on her northern as well as on her southern

border. No doubt, too, France feared that her great rival would

soon seek to drive her golden lilies back to the Old World, for

New France would be a wedge between the northern and southern

possessions of England in the New World.

The movement leading to the first voyage to

Hudson Bay by Gillam and his company was carefully watched by the

French Government. In February, 1668, at which time Gillam's

expedition had not yet sailed, the Marquis de Denonville, Governor

of Canada, appointed an officer to go in search of the most

advantageous posts and occupy the shores of the Baie du Nord and

the embouchures of the rivers that enter therein. Among other

things the governor gave orders "to arrest especially the said

Radisson and his adherents wherever they may be found."

Intendant Talon, in 1670, sent home word to

M. Colbert that ships had been seen near Hudson Bay, and that it

was likely that they were English, and were "under the guidance of

a man des Grozeliers, formerly an inhabitant of Canada."

The alarm caused the French by the movements

of the English adventurers was no doubt increased by the belief

that Hudson Bay was included in French territory. The question of

what constituted ownership or priority of claim was at this time a

very difficult one among the nations. Whether mere discovery or

temporary occupation could give the right of ownership was much

questioned. Colonization would certainly be admitted to do so,

provided there had been founded "certain establishments." But the

claim of France upon Hudson Bay would appear to have been on the

mere ground of the Hudson Bay region being contiguous or

neighbouring territory to that held by the French.

The first claim made by France was under the

commission, as Viceroy to Canada, given in 1540 by the French King

to Sieur de Roberval, which no doubt covered the region about

Hudson Bay, though not specifying it. In 1598 Lescarbot states

that the commission given to De La Roche contained the following:

"New France has for its boundaries on the west the Pacific Ocean

within the Tropic of Cancer; on the south the islands of the

Atlantic towards Cuba and Hispaniola; on the east, the Northern

Sea which washes its shores, embracing in the north the land

called Unknown toward the Frozen Sea, up to the Arctic Pole."

The sturdy common sense of Anglo-Saxon

England refused to be bound by the contention that a region

admittedly "Unknown" could be held on a mere formal claim.

The English pointed out that one of their

expeditions under Henry Hudson in 1610 had actually discovered the

Bay and given it its name; that Sir Thomas Button immediately

thereafter had visited the west side of the Bay and given it the

name of New Wales; that Captain James had, about a score of years

after Hudson, gone to the part of the Bay which continued to bear

his name, and that Captain Fox had in the same year reached the

west side of the Bay. This claim of discovery was opposed to the

fanciful claims made by France. The strength of the English

contention, now enforced by actual occupation and the erection of

Charles Fort, made it necessary to obtain some new basis of

objection to the claim of England.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that a

deliberate effort was made to invent some ground of prior

discovery in order to meet the visible argument of a fort now

occupied by the English. M. de la Potherie, historian of New

France, made the assertion that Radisson and Groseilliers had

crossed from Lake Superior to the Baie du Nord (Hudson Bay). It is

true, as we have seen, that Oldmixon, the British writer of a

generation or two later, states the same thing. This claim is,

however, completely met by the statement made by Radisson of his

third voyage that they heard only from the Indians on Lake

Superior of the Northern Bay, but had not crossed to it by land.

We have disposed of the matter of his fourth voyage. The same

historian also puts forward what seems to be pure myth, that one

Jean Bourdon, a Frenchman, entered the Bay in 1656 and engaged in

trade. It was stated also that a priest, William Couture, sent by

Governor D'Avaugour of New France, had in 1663 made a missionary

establishment on the Bay. These are unconfirmed statements, having

no details, and are suspicious in their time of origination. The

Hudson's Bay Company's answer states that Bourdon's voyage was to

another part of Canada, going only to 53° N., and not to the Bay

at all. Though entirely unsupported, these claims were reiterated

as late as 1857 by Hon. Joseph Cauchon in his case on behalf of

Canada v. Hudson's Bay Company. M. Jeremie, who was Governor of

the French forts in Hudson Bay in 1713, makes the statement that

Radisson and Groseilliers had visited the Bay overland, for which

there is no warrant, but the Governor does not speak of Bourdon or

Couture. This contradiction of De la Potherie's claim is surely

sufficient proof that there is no ground for credence of the

stories, which are purely apocryphal. It is but just to state,

however, that the original claim of Roberval and De la Roche had

some weight in the negotiations which took place between the

French and English Governments over this matter.

M. Colbert, the energetic Prime Minister of

France, at any rate made up his mind that the English must be

excluded from Hudson Bay. Furthermore, the fur trade of Canada was

beginning to feel very decidedly the influence of the English

traders in turning the trade to their factories on Hudson Bay. The

French Prime Minister, in 1678, sent word to Duchesnau, the

Intendant of Canada, to dispute the right of the English to erect

factories on Hudson Bay. Radisson and Groseilliers, as we have

seen, had before this time deserted the service of England and

returned to that of France. With the approval of the French

Government, these facile agents sailed to Canada and began the

organization, in 1681, of a new association, to be known as "The

Northern Company." Fitted out with two small barks, Le St. Pierre

and La Ste. Anne, in 1682, the adventurers, with their companions,

appeared before Charles Fort, which Groseilliers had helped to

build, but do not seem to have made any hostile demonstration

against it. Passing away to the west side of the Bay, these shrewd

explorers entered the River Ste. Therese (the Hayes River of

to-day) and there erected an establishment, which they called Fort

Bourbon.

This was really one of the best trading

points on the Bay. Some dispute as to even the occupancy of this

point took place, but it would seem as if Radisson and

Groseilliers had the priority of a few months over the English

party that came to establish a fort at the mouth of the adjoining

River Nelson. The two adventurers, Radisson and Groseilliers, in

the following year came, as we have seen, with their ship-load of

peltries to Canada, and it is charged that they attempted to

unload a part of their cargo of furs before reaching Quebec. This

led to a quarrel between them and the Northern Company, and the

adroit fur traders again left the service of France to find their

way back to England. We have already seen how completely these two

Frenchmen, in the year 1684, took advantage of their own country

at Fort Bourbon and turned over the furs to the Hudson's Bay

Company.

The sense of injury produced on the minds of

the French by the treachery of these adventurers stirred the

authorities up to attack the posts in Hudson Bay. Governor

Denonville now came heartily to the aid of the Northern Company,

and commissioned Chevalier de Troyes to organize an overland

expedition from Quebec to Hudson Bay. The love of adventure was

beginning to feel very decidedly the influence of the English

traders in turning the trade to their factories on Hudson Bay. The

French Prime Minister, in 1678, sent word to Duchesnau, the

Intendant of Canada, to dispute the right of the English to erect

factories on Hudson Bay. Radisson and Groseilliers, as we have

seen, had before this time deserted the service of England and

returned to that of France. With the approval of the French

Government, these facile agents sailed to Canada and began the

organization, in 1681, of a new association, to be known as "The

Northern Company." Fitted out with two small barks, Le St. Pierre

and La Ste. Anne, in 1682, the adventurers, with their companions,

appeared before Charles Fort, which Groseilliers had helped to

build, but do not seem to have made any hostile demonstration

against it. Passing away to the west side of the Bay, these shrewd

explorers entered the River Ste. Therese (the Hayes River of

to-day) and there erected an establishment, which they called Fort

Bourbon.

This was really one of the best trading

points on the Bay. Some dispute as to even the occupancy of this

point took place, but it would seem as if Radisson and

Groseilliers had the priority of a few months over the English

party that came to establish a fort at the mouth of the adjoining

River Nelson. The two adventurers, Radisson and Groseilliers, in

the following year came, as we have seen, with their ship-load of

peltries to Canada, and it is charged that they attempted to

unload a part of their cargo of furs before reaching Quebec. This

led to a quarrel between them and the Northern Company, and the

adroit fur traders again left the service of France to find their

way back to England. We have already seen how completely these two

Frenchmen, in the year 1684, took advantage of their own country

at Fort Bourbon and turned over the furs to the Hudson's Bay

Company.

The sense of injury produced on the minds of

the French by the treachery of these adventurers stirred the

authorities up to attack the posts in Hudson Bay. Governor

Denonville now came heartily to the aid of the Northern Company,

and commissioned Chevalier de Troyes to organize an overland

expedition from Quebec to Hudson Bay. The love of adventure was

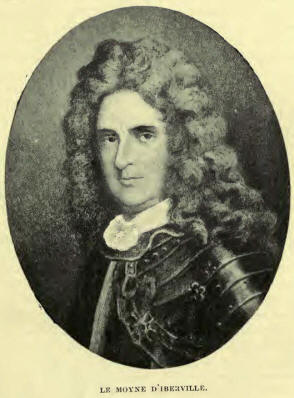

strong in the breasts of the young French noblesse in Canada. Four

brothers of the family Le Moyne had become known for their deeds

of valour along the English frontier. Leader among the valorous

French-Canadians was Le Moyne D'Iber-ville, who, though but

twenty-four years of age, had already performed prodigies of

daring. Maricourt, his brother, was another fiery spirit, who was

known to the Iroquois by a name signifying "the little bird which

is always in motion/' Another leader was Ste. Helene. With a party

of chosen men these intrepid spirits left the St. Lawrence in

March, 1685, and threaded the streams of the Laurentian range to

the shore of Hudson Bay.

After nearly three months of the most

dangerous and exciting adventures, the party reached their

destination. The officers and men of the Hudson's Bay Company's

service were chiefly civilians unaccustomed to war, and were

greatly surprised by the sudden appearance upon the Bay of their

doughty antagonists. At the mouth of the Moose River one of the

Hudson's Bay Company forts was situated, and here the first attack

was made. It was a fort of considerable importance, having four

bastions, and was manned by fourteen guns. It. however, fell

before the fierce assault of the forest rangers, The chief offence

in the eyes of the French was Charles Fort on the Rupert River,

that being the first constructed by the English Company. This was

also captured and its fortifications thrown down. At the same time

that the main body were attacking Charles Fort, the brothers Le

Moyne, with a handful of picked men, stealthily approached in two

canoes one of the Company's vessels in the Bay and succeeded in

taking it.

The largest fort on the Bay was that in the

marshy region on Albany River. It was substantially built with

four bastions and was provided with forty-three guns. The rapidity

of movement and military skill of the French expedition completely

paralyzed the Hudson's Bay Company officials and men. Governor

Sargeant, though having in Albany Fort furs to the value of 50,000

crowns, after a slight resistance surrendered without the honours

of war. The Hudson's Bay Company employes were given permission to

return to England and in the meantime the Governor and his

attendants were taken to Charlton Island and the rest of the

prisoners to Moose Fort. D'Iberville afterwards took the prisoners

to France, whence they came back to England.

A short time after this the Company showed

its disapproval of Governor Sargeant's course in surrendering Fort

Albany so readily. Thinking they could mark their disapprobation

more strongly, they brought an action against Governor Sargeant in

the courts to recover 20,000Z. After the suit had gone some

distance, they agreed to refer the matter to arbitration, and the

case was ended by the Company having to pay to the Governor 350l.

The affair, being a family quarrel, caused some amusement to the

public.

The only place of importance now remaining to

the English on Hudson Bay was Port Nelson, which was near the

French Fort Bourbon. D'Iberville, utilizing the vessel he had

captured on the Bay, went back to Quebec in the autumn of 1687

with the rich booty of furs taken at the different points.

These events having taken place at a time

when the two countries, France and England, were nominally at

peace, negotiations took place between the two Powers.

Late in the year 1686 a treaty of neutrality

was signed, and it was hoped that peace would ensue on Hudson Bay.

This does not seem to have been the case, however, and both

parties blame each other for not observing the terms of the Act of

Pacification. D'Iberville defended Albany Fort from a British

attack in 1689, departed in that year for Quebec with a shipload

of furs, and returned to Hudson Bay in the following year. During

the war which grew out of the Revolution, Albany Fort changed

hands again to the English, and was afterwards retaken by the

French, after which a strong English force (1692) repossessed

themselves of it. For some time English supremacy was maintained

on the Bay, but the French merely waited their time to attack Fort

Bourbon, which they regarded as in a special sense their own. In

1694 D'Iberville visited the Bay, besieged and took Fort Bourbon,

and reduced the place with his two frigates. His brother De

Chateauguay was killed during the siege.

In 1697 the Bay again fell into English

hands, and D'Iberville was put in command of a squadron sent out

for him from Prance, and with this he sailed for Hudson Bay. The

expedition brought unending glory to France and the young

commander. Though one of his warships was crushed in the ice in

the Hudson Straits and his remaining vessels could nowhere be seen

when he reached the open waters of the Bay, yet he bravely sailed

to Port Nelson, purposing to invest it in his one ship, the

Pelican. Arrived at his station, he observed that he was shut in

on the rear by three English men-of-war. His condition was

desperate ; he had not his full complement of men, and some of

those on board were sick. His vessel had but fifty guns ; the

English vessels carried among them 124. The English vessels, the

Hampshire, the Bering, and the Hudson's Bay, all opened fire upon

him. During a hot engagement, a well-aimed broadside from the

Pelican sank the Hampshire with all her sails flying, and

everything on board was lost; the Hudson's Bay surrendered

unconditionally, and the Dering succeeded in making her escape.

After this naval duel D'lberville's missing vessels appeared, and

the commander, landing a sufficient number of men, invested and

took Port Nelson. The whole of the Hudson Bay territory thus came

into the possession of the French. The matter has always, however,

been looked at in the light of the brilliant achievement of this

scion of the Le Moynes.

Few careers have had the uninterrupted

success of that of Pierre Le Moyne D'Iberville, although this

fortune reached its climax in the exploit in Hudson Bay. Nine

years afterwards the brilliant soldier died of yellow fever at

Havana, after he had done his best in a colonization enterprise to

the mouth of the Mississippi which was none too successful. Though

the treaty of Ryswick, negotiated in this year of D'Iberville's

triumphs, brought for the time the cessation of hostilities, yet

nearly fifteen years of rivalry, and for much of the time active

warfare, left their serious traces on Hudson's Bay Company

affairs. A perusal of the minutes of the Hudson's Bay Company

during this period gives occasional glimpses of the state of war

prevailing, although it must be admitted not so vivid a picture as

might have been expected. As was quite natural, the details of

attacks, defences, surrenders, and parleys come to us from French

sources rather than from the Company's books. That the French

accounts are correct is fully substantiated by the memorials

presented by the Company to the British Government, asking for

recompense for losses sustained.

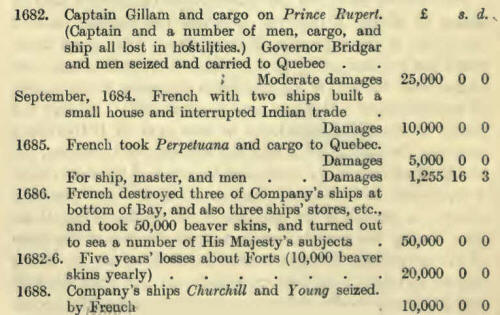

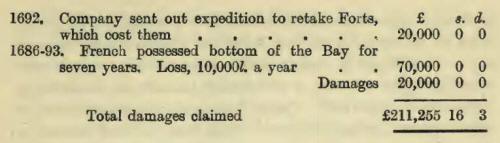

In 1687 a petition was prepared by the

Hudson's Bay Company, and a copy of it is found in one of the

letter-books of the Company. This deals to some extent with the

contention of the French king, which had been lodged with the

British Government, claiming priority of ownership of the regions

about Hudson Bay. The arguments advanced are chiefly those to

which we have already referred. The claim for compensation made

upon the British Government by the Company is a revelation of how

seriously the French rivalry had interfered with the progress of

the fur trade. After still more serious conflict had taken place

in the Bay, and the Company had come to be apprehensive for its

very existence, another petition was laid before His Majesty

William III., in 1694. This petition, which also contained the

main facts of the claim of 1687, is so important that we give some

of the details of it. It is proper to state, however, that a part

of the demand is made up of what has since been known as

"consequential damages," and that in consequence the matter

lingered on for at least two decades.

The damages claimed were :—