|

AS showing the values

in Casey Township, another mine in this locality has recently been sold

in London for $1,000,000. It is the Casey Mine, discovered on the John

Bucknall farm. IJe was the first man to discover cobalt bloom in this

section. This was followed by the discover}- of silver by W. S.

Mitchell, one of the most enterprising young men in the whole Cobalt

district. Mr. Mitchell, a representative of a great banking house of

London, came to Canada two years ago, and has already become identified

with some of the most valuable properties in Northern Ontario. He is one

of the few who are never satisfied to follow in the track of other

prospectors. He must ever lead. He and his unique band of prospectors

were the first to find mineral outside the beaten track. He found gold

in Playfair Township a month before Dr. Reddick made his famous

discovery at Larder Lake. His Town site Mine, in Cobalt, was the first

Cobalt mine to be listed on any of the great exchanges of London, New

York, etc. They were first to discover silver in Casey, and among the

first to discover silver in the surveyed part of James, up the Montreal

River. The story of the hardships of his band of prospectors, while up

this wild river, is a most entertaining one, as may be seen further on

in my own story of this young man.

He is a great

organizer. It was he who organized the Elk Lake Silver Mines, Limited,

with large holdings in James. Another of his enterprises is the

Oposatica, and Chibogamoo Exploration Company, now exploring the mineral

lands of the Province of Quebec. His Airgiod Co. has among its members

some of the most prominent Scotchmen in Canada—many being members of the

Dominion Parliament, Senators, and successful men of affairs.

Mr. Mitchell has other

valuable properties in Coleman, not yet organized.

Being a resident of

Haileybury, he is taking a most active interest in the upbuilding of

this Wonder City of the North, which such as he are making to grow with

marvellous rapidity, as may be seen in my chapter on “Haileybury.”

Mr. Mitchell's Montreal

River Finds

As above, Mr.

Mitchell’s party were among the first to prospect, successfully, in the

surveyed part of James.

By reason of the

personnel of the men composing this party, it is doubtless the most

unique among prospectors of New Ontario. There were Jack Munroe, who

once made matters so interesting for big Jim Jeffries; Joe Acton,

champion lightweight wrestler of England; Jack Hammell, the cosmopolitan

humorist, and clever writer; Tom Saville, “The White Indian,” a noted

guide; and Mose, “The Hungry Indian.” Later the party was joined by

surveyor Charles Fullerton, of New Liskeard, and Neil Sharpe.

The Diary of the Two

Jacks

I was shown the diary

kept by Munroe and Hammell. In it was a graphic account of their first

trip up the Montreal. It tells of the hardships they endured while

searching for silver claims. While Munroe gives the serious side,

HammelFs sense of humor crops out in every line, making his part of the

“log” a most entertaining chapter. He might be half starved and yet

could laugh at poor Hungry Mose’s Oliver Twist-like calls for “More!

More!” He might be all but frozen and yet smile at Neil Sharpe’s frozen

ears—taking out the stings with his laughter.

It was in the dead of

winter. On the last day of December, 1906, they ran out of provisions.

Latchford was the nearest point at which they could replenish their

store—and Latchford 55 miles away! The tossing of a penny decided who

should make the return trip. These were sent by the penny: Jack Munroe,

Acton and Saville, leaving Jack Hammell to look after Mose-the-Hungry.

As soon as the return

party had gone, Hammell took up the diary. He started in with a

resolution to begin the year without drinking. Next day he writes: “Am

still on the water waggon.” Munroe said afterward: “No wonder, for we

had taken what little there was left.”

Jan. 1: “Been chasing

six-hour-old moose tracks all day. First I lost the Indian, then lost my

fool self. Somebody had side-tracked the scenery. Think I must have

walked 1,000 miles before I located the camp.”

Jack did a bit of

snowshoeing one day. “Crust just hard enough to let you break through

and enable your shoes to sneak underneath, so as when you go to lift

your foot you bring a ton of crust along with it. As for going down the

hills, I generally slide them. To-day I flopped and then dived them.

First your feet break through, then the dive starts. I am champion

acrobatic hunter. Oh, if only the 42nd Street bunch could see me now,

they sure would laugh! This woods life is the only life! Great for

people with strong backs and weak minds!”

A day or two later Jack

laments: “No food in sight yet! If the boys don’t soon come we’ll have

to stew up the moccasins and snowshoes. Indian says, ‘Him hungry!’ That

Indian is always hungry! Can’t blame him, though, to-night—have almost

forgotten how to eat, myself. Oh for a look in at Del-monico’s with the

boys! This woods life is so different—No, can’t blame the Indian!”

From famine to feast!

Munroe and party got back the next morning, and Hammell is said to have

got off the “ water waggon ” before nine.

Munroe takes up the

diary, and tells of the hardships of the 55 miles return to Latchford

for supplies. They ran out of all food but a little bannock (Indian

bread), which they had to divide up between the three.

The Squirrel Chase In

the Cabin

One night they stopped

in an old lumber camp in which a squirrel had locatcd. After a long

chase around the big room, Jack caught it. The other boys claimed that

Jack called lustily for them to “come quick and help me hold it.” But

the boys do say lots o’ things about big, good-natured Jack. The only

thing they could get to cook it in was a tobacco can they found. A

little corn meal—very old—was also found, and with it and the squirrel,

a tasty broth was made. For the squirrel they cast lots for the parts,

and sat down to a contented feast.

“Shou Me the Mon 'Oo It

Me With a Brick!”

At another time, when

the whole party were together, they were sleeping in a lumber camp with

a dozen or more lumbermen. It is the custom, in very cold weather, to

sleep in their clothes—boots and all. To preface this story I must tell

you that Tom Saville had a dog that had a way of crawling in among the

sleepers to keep warm. He crawled in with Jack Hammell this night—as

Jack thought. Jack was sure of it, for he could feel the dog’s hair

rubbing against his face. Now Jack did not object to the dog sleeping

with him, providing he slept at the “foot,” but he drew the line at “the

head,” and especially his head. “Get out, you beast!” said Jack, and

emphasized it with his fist. Imagine his surprise at having Joe Acton

jump up, with a loud yell, and as he pranced around the cabin over the

sleepers, wanting to know: “Wough, hl’m ’it! ’Oo ’it me? Shou me the mon

’oo ’it me with a brick!” But everybody was asleep, and Jack Hammell was

snoring loudest of all, for he respected Joe’s reputation of being able

to look after himself. Joe related his night’s experience next morning,

and was surprised that nobody should have known of it. “Didn’t you ’ear

me, Jack? W’y, you were right next me!”

“Never heard a sound! I

sleep tight when once I start,” said Jack, with the faintest sort of a

smile.

The weather was bitter

cold along about Jan. 13th. The diary says: “Very cold. Neil’s face

froze several times. We had to watch each other all the while to keep

from freezing.”

Many Valuable Claims

Staked

With all their

hardships they returned with many valuable claims staked. Some of them

will turn out to be great mines, as the work already done indicate

wonderful things to come.

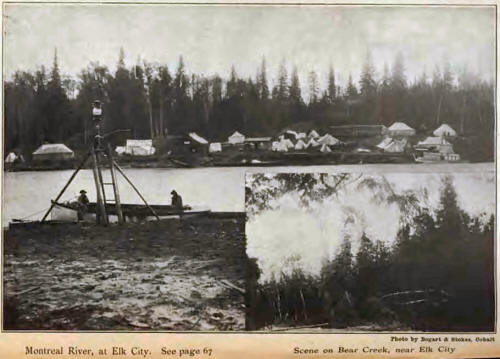

That was but a few

months ago. They were among the pioneers of many thousands of

prospectors who have gone into the Montreal River country. Where was

then a wilderness, is now a busy camp, with towns springing up, and

before the year is out, much of the valley from Latchford to the height

of land will be looked upon as an “ Old Camp,” so rapid follows

improvement in a mining country.

I must not leave out

one of Jack Hammell’s best. It’s one that the boys tell on him. It

happened just before they returned from Latchford with the supplies. He

and Mose were down to the bottom of the “barrel,” and were both pretty

hungry for meat. As they sat around exchanging experiences, Jack started

in.

Jack Makes a Good Shot

“Oh, I didn’t tell you,

did I? Well, Mose hasn’t spoken to me all day, just because I batted him

one with a hunk of tree. It was this way: I goes for a pail of water

this morning, and, coming back, I spies a big, voluptuous partridge

right up in a tree, just in front of the tent, so I calls to Mose, ‘Hey,

Mose,’ says I, soft like, ‘ grab something and come quick, there’s a

great big partridge up this tree. It’s meat for us, if you’re a good

shot.’ So Mose he grabs a stick of wood and steps out of the tent. ‘Now

be careful,’ I tells him, ‘and don’t breathe heavy, and when I counts

three, let loose at him.’ Old Mose he sets himself. You’d have thought

he was gettin’ ready to fight a grizzly by the look on his face. But

somehow things didn’t go just right. Old Mose he couldn’t hold himself,

for when I got to the ‘Two' count, it was all off. Mose couldn’t wait

any longer. He just had to take a swash at him, and me, Mr. Simp, not

wanting to be out of it, took a clout at him on the fly. Missed him, of

course—that is, the bird, but not the shot. No, Mose he grabbed it right

below the belt. Well, you should have seen that Indian’s face—the hurt

look he threw at me! He immediately sat down and commenced hugging

himself with both hands. He wouldn’t even notice me. In fact, it was

some little time until I could get Mose to sit up and take notice to

anything. Finally he stopped loving himself, got up and sauntered away,

muttering something about some people being—poor shots, which was an

injustice to me, for if ever a man made a pretty shot it was me, with

that hunk of tree. It just goes to show, though, how dense some Indians

are. They never seem to look at things in a broad-minded light.

Sometimes I think that Mose’s mind must be bad, otherwise he wouldn’t

mind a little thing like that.”

Later.—Poor Mose is

dead—died late in the fall—shortly after my trip up the Montreal, of

which I shall tell you further on. I met Mose at Elk Lake City. I had

thought him the typical, high cheek bone, tall, blanketted and—well, the

picture-book Indian. He was so different that I could scarce believe

that the well-dressed boy I saw at Elk Lake City was the same as he of

whom I had heard so much—Poor “Hungry Mosel” Hungry no longer.

Coomstock Lode to be

Surpassed by Cobalt

But to return to Mr.

Mitchell. He has made a deep study of the situation in the Cobalt Camp.

“Look at that,” said he, during one of my interviews with him. “ That, ”

was the United States Mineral Report. The particular part to which he

called my attention was the world-famous Comstock Lode of Nevada. “Now

see,” said he, “up to 1900 there was taken out $203,636,-062.84 of

silver. It took 40 years to take this out, and they had to go down 3,300

feet to get it. The greatest year was 1874—

the fifteenth from its

start in 1859—when the production was $21,780,922.02. Now follow. This

will be equalled, in 1909, by the Cobalt district, the fourth year after

machinery was installed.” I could scarcely realize this, but when he

showed what is being taken out from the mines now shipping, and with

such mines as the Cobalt Lake, Nancy-Helen, North Cobalt, and a dozen

others, now almost ready to start in as big shippers, I had to admit the

correctness of his prediction. Only to-day, I visited a mine, and

watched the men bagging ore at the rate of a carload every twenty-four

hours. Marvellous! And again, wonderful, this story of Cobalt and its

fabulous wealth of silver.

Later.—They struck a

rich vein in the Casey, just as this goes to press, that runs 5,300

ounces of silver.

THE IMPERIAL LARDER LAKE

AMALGAMATED MINES

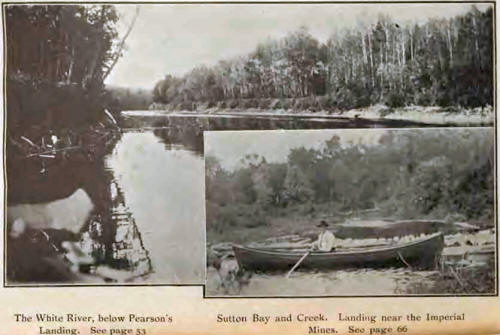

This Company, with head

office in New Liskeard, Ont., whose low capitalization and large

holdings of 43 well-selected claims, in the rich parts of the Larder

Lake district, and in the townships of Boston, Catherine, and Harris,

must become one of the successful mining enterprises of the country.

It has had assays of

$1,354 in gold, with good showings of copper and silver, in their

township claims. Its capitalization is but $250,000, with shares at par

$1. Only enough of which will be sold to develop the properties, and not

run as a stockjobbing enterprise. The high standing of its officers and

directors is a guaranty of honest management.

I have not seen their

other holdings, but I have visited their mine in Harris Township, and

from it judge the carefulness of the company. These are in the joining

concessions to the Casey Mines, recently sold in London for $1,000,000,

and the $5 par 9hares of which have already reached above $7. The

formation of the rock in exactly the same as the Casey, and is growing

richer as they go down.

The officers and

directors are all successful business men of New Liskeard, and have gone

into the matter as an honest business enterprise: President, George

Weaver, Real Estate Agent and Mining Broker, and Vice-President of the

Temiskaming Telephone Co., Ltd.; Vice-President, R. G. Zahalan, hotel

proprietor; Secretary-Treasurer, G. W. Weaver. Directors: Frank Loudin

Smiley, Barrister; Henri Loudin, Business Manager; J. H. Obrien,

Contractor; W. J. Yates, Merchant; and W. E. Kerr, Government Inspector

of Roads.

Solicitors: Hartman and

Smiley. Bankers: Imperial Bank of Canada. |